A recurring theme in discussion of digital writing technologies is the unprecedented freedom they offer both writer and reader; freedom from the constraints not only of paper and of place, but of linearity, hierarchy, and passive receptivity, among other limitations of tangible media-based print. There is also considerable celebration (if conspicuously less actual use) of the potential for enhancement through image of ideas and genres traditionally expressed entirely in text. But much less is said about the areas in which these technologies may have quite a contrary effect; for example, impact on demographic and other survey-based information, use of and resistance to bureaucratic forms, and what can be lost both in the present and from the historical record in terms of personalization, subtext, and incidental and unintentional artefact, in a shift to increased use of digital media. Although there is a great deal of flexibility possible in these technologies, there is also increased homogeneity, restriction of ability to resist and subvert bureaucracy, and potential great loss of contextual insight.

Two areas particularly interest me: the effects of digitization on forms and related information gathering tools; and the implications of the disappearance of physical documents such as forms, letters and printed photographs. The following essay offers a brief look at each.

Required Fields and Invalid Responses

Jay David Bolter devotes most of Chapter 6 in his book Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print to the implications of hypertext for writers and writing in particular. “If linear and hierarchical structures dominate current writing, our cultural construction of electronic writing is now adding a third: the network as a visible and operative structure” (106). Bolter acknowledges the network as a very ancient “organizing principle” of writing; now, Bolter maintains, the network can “rise to the surface” of the text.

Bolter continues to illustrate how hypertext has the potential to be non-linear, non-hierarchical, interactive, and dialogic. Bolter is interested in the writer’s perspective, but the implication is equally clear for the reader, who is freed from a traditionally passive role. Gunther Kress is gleeful about the social effects of this power newly offered to the reader:

The screen offers the facility in ways that the book did not . . . for the reader to become author . . . I can change the text that comes to me on the screen. . . . That factor, of course, brings about a radical change to notions of authority: When everyone can be an author authority is severely challenged. The social frames that had supported the figure of the author have disappeared or are disappearing and with that the force of social power that vested authority in the work of the author (19).

The overall picture they paint is of collapsing walls and expanding vistas – a new era of possibility in writing and reading facilitated by digital technology, in which their user or audience invoked invariably has both full access and unfettered use. Their enthusiasm is shared by many theorists and users.

But while theorists re-imagine the structure of text and its implications for writing in hyperspace, and the flower children of the world wide web ‘reach out’ to each other in an orgy of blogging and friend-making, institutions and bureaucracies discover their own uses for new technologies. In the realm of forms and official documents, where traditionally the roles of writer and reader meet and cross, the digital environment is increasingly used to enforce separation and inflexibility.

Bolter and Kress overlook the traditionally non-linear and non-hierarchical possibilities in these types of writing, which are lost as they become electronic. In what was one of the few aspects of print where the reader could talk back as writer, the relationship between text and reader has become increasingly rigid, unidirectional, even dictatorial. The reader’s traditional power to resist the writer’s agenda by leaving demands unanswered, writing complex responses across divides of restrictively small spaces, commenting in margins or on the back of the sheet, and so on, has been eliminated.

In a digital age and environment the aims of the designers of a form or template can finally find their fullest realization. The freedom of the reader to resist a passive role, to step beyond reactive compliance, to write what is rather than what is expected, accepted, acknowledged, or allowed, can at last be effectively curtailed.

The result is an increasing occurrence of online and electronic forms – surveys, reports, applications, evaluations, purchase orders, and many others – in which the user’s options are severely limited. Many of these are driven by economic interests; among them a desire to save considerable expense on data collection and analysis, and a cultural preference everywhere from academia to industry to government, for quantitative information. Opportunities to comment are available at the discretion of a form’s author, but may also reflect bias, as in the case of a university department reviewing its programs, which included 13 open comment fields in its survey of faculty and two in its survey of students[i]. Others are filled with responses from a prepared set, rather than individually composed; an example is report card software with ‘comment libraries’, which may serve a perceived desire for consistency (uniformity?) and be intended to save time, but also limit the reader/author to saying only those things which the author/reader deemed appropriate or thought to include. Ironically, this environment is powerfully reminiscent of Kress’ characterization of traditional print, in which “[o]rder is firmly coded” (7).

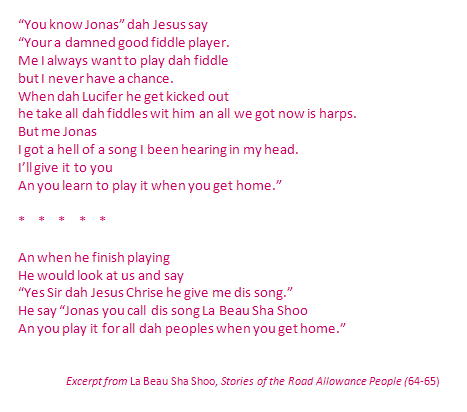

Figure 1: An example of fields in a form designed using an online survey utility.

In this example of an online form[ii], the Full name field allows only 25 characters – fewer than this user needs. Date of birth is required, and for Gender choices are the traditional male or female. The potential negative effects are clear. Certain elements of the user’s reality are denied as possibilities: a long name; a non-traditional gender identity; uncertainty about date of birth – unimaginable in Western culture, but common in many places; in regard to any facet of interrogation, a desire to maintain privacy. Answers for which the form’s author has made no provision – for whatever reason – may be rejected as an ‘Invalid Response’.

Even the pop-up box directing the user to complete required fields allows only one response – ‘OK’. Many such ‘interfaces’ offer only a few pre-scripted responses – e.g. ‘now’ or ‘later’, for an action which the user may not wish to take at all.

These requirements and omissions can create alienation, barriers to service, and misunderstandings or misrepresentations through relying on information so gathered. The denial in a single form of alternative gender identity may seem trivial, but in both language and statistics that which is not named appears not to exist. When this question appears so in, for example, a census form, the statement to citizens from government is that it recognizes no other gender identities. And any law or social policy based on the data would reflect only these two possibilities.

The cumulative effect is, as Neil Postman presciently wrote in 1992, that “[t]heir private matters have been made more accessible to powerful institutions. They are more easily tracked and controlled; are subject to more examinations; are increasingly mystified by the decisions made about them; are often reduced to mere numerical objects” (10).

Compare these characteristics of electronic forms with this traditional paper example.

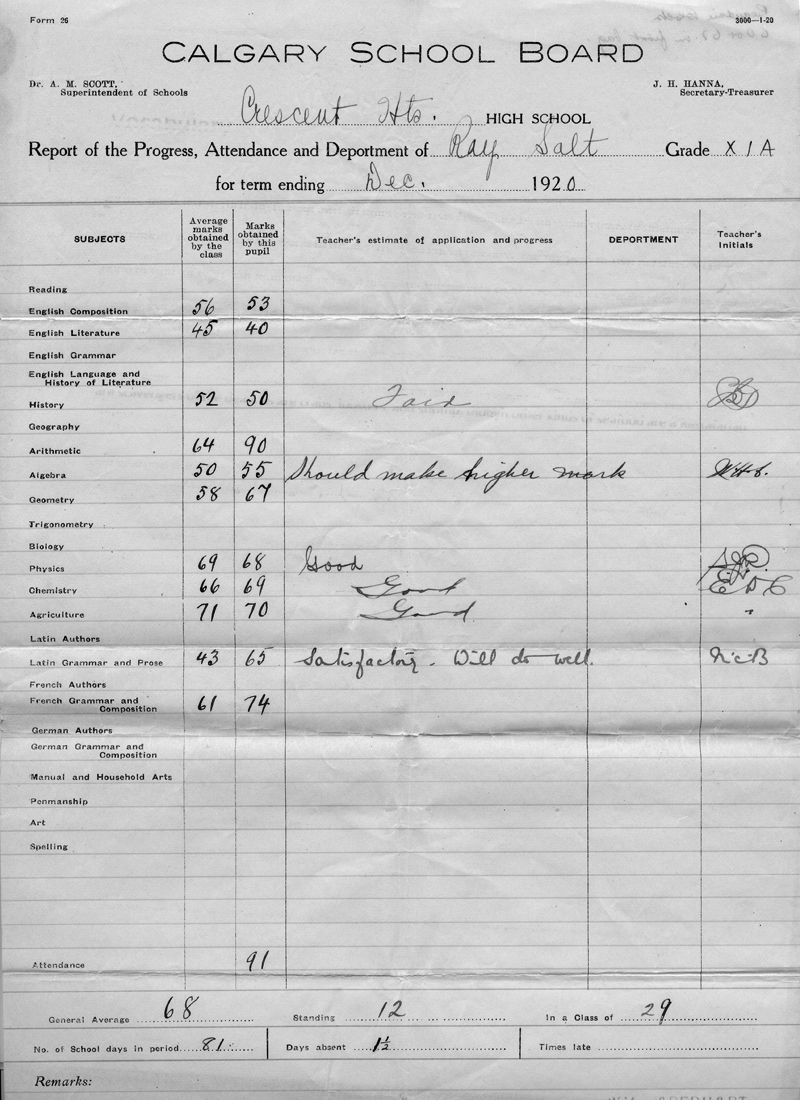

Figure 2: Calgary School Board high school reporting form, completed in December 1920.

The Calgary School Board has indicated how it wants teachers to report on the Progress, Attendance and Deportment of students. DEPORTMENT is given prominence with bold uppercase, but not one teacher who contributed to this pupil’s report chose to comment in that column[iii]. Teachers have made the priority of deportment to them just as clear as has the school board.

Though this may seem trivial, it has significant potential to convey shifting priorities, and to resist bureaucratic dictation at the ‘front lines’ of work. Similarly the record left for history reveals both what was elicited and what was produced – and the nature of any gap between them.

My Grandfather’s House

Personal mementos also suffer a loss of dimension in entering the digital world. Most people have had the experience of looking through old family papers and photographs – finding yellowed letters and dog-eared snapshots of parents and grandparents and even great-grandparents. Many interesting insights come through pieces that were not necessarily saved for posterity; they are often the unexpected fruit of incidental artefacts, items filed temporarily and then forgotten.

It is almost reflexive – at least for older people[iv] – to turn photos over and look on the back for a name, date, place, or some other glimpse into their origins. Although we think of these images on paper as having but two dimensions, they in effect have three – the ‘back story’ adds depth, sometimes well beyond the words themselves. Handwriting may be recognized, giving context to incomplete, vague or cryptic notes. “Grandpa MacDougall’s house” describing a photo leaves questions lingering in type that are answered by your grandmother’s distinctive script. A photographer’s imprint, the photo paper, film lab’s package or mailer, even a frame or an album and mounting materials add context. Their absence is more than merely a loss in the tactile element of documentary history.

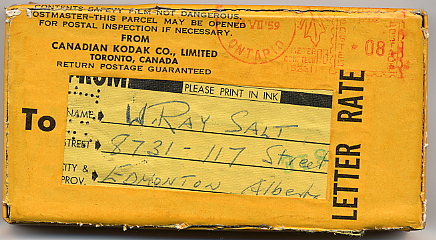

The example below of a Kodak slide mailer shows some of the insight and context that may be provided quite incidentally.

Figure 3: Kodak photo processing return mailer, 1959.

The photographer, most likely the addressee, lived in Edmonton, Alberta (his residence can be pinpointed on a map should a researcher wish to do so). Those who knew him well could also identify him here by his handwriting. The postmark gives an approximate date to the photographs within – July 1959. At that time this little package – measuring about 11cm x 6cm x 1.5 cm – could be sent by letter post for eight cents, from Toronto (suggesting that Kodak had no labs closer than that to Edmonton). By looking at the photos themselves one can learn also that he is a skilled photographer, with high standards – as evidenced by the quality of the photos, and the fact that in spite of it he has noted on the back of the box, “BIRDS. Not good” – and with a tendency to keep even his unsatisfactory work carefully filed.

Letters are likewise filled with information beyond what the words themselves convey, encoded in handwriting, illustrations, paper, envelope, postage, postmark, stamp, layout of page and density of writing, and any additional marks such as seals, recipient’s notations (handwritten or stamped), and any scars of passage.

It is likely that the almost complete digitization of personal communication in some parts of the world will soon result in, among other things, a generation of children who may never have received a personal letter by post, are even less likely to have written one, and very possibly would not recognize the handwriting of any but their closest family members. Casual interpersonal communication is generated at an ever accelerating rate but is increasingly ephemeral and without context. Even formal letters now rarely include the traditional header providing date and place of their writing, and email messages are characterized by casual style that often omits even a salutation.

As explained by handwriting expert Rosemary Sassoon, “[a]n individual sample of handwriting reflects the writer’s training, character and environment. Collectively, the handwriting of a population of any period is a reflection of educational thinking, but overall it is influenced and ultimately moulded by economic need, social habits and contemporary taste” (9). On a personal level handwriting can be powerfully evocative, especially the writing of someone loved but no longer living. Bolter and Kress and their fellow enthusiasts apparently overlook the fact that writing, produced by the human hand, inherently straddles the divide between text and image, conveying both literal meaning and at least a few hundred of the proverbial ‘thousand words’ of pictorial richness.

Ultimately, the effect of digital media on personal memento may be quite the opposite of what its proponents have expected and declared. Rather than the facilitation and proliferation of unique and personal archives and aides-mémoire, the result may be an increasing bulk of material with ever fewer individualizing characteristics.

Ecological Change

Writers such as Bolter discuss traditional prose, fiction and non-fiction and academic writing, while others are interested in myriad ways of using hypertext to expand the possibilities of educational materials, artistic expression, personal memoir, alternative approaches to publishing, and implications for copyright, collaboration and cultural entitlement. While the advantages they see in hypertext are real for all these forms, and while the forms discussed in this essay differ significantly in structure and function, they are all part of a larger social whole. What are the implications for a society in which people are able to express themselves with ever greater flexibility and variety in creative ways but quite the opposite in their interactions with the state; and in which personal memento becomes increasingly ephemeral, two dimensional, and homogeneous? Such questions are inevitable, as Neil Postman recognized, “when one grasps, as Thamus did, that . . . it is not possible to contain the effects of a new technology to a limited sphere of human activity. . . . Technological change is neither additive nor subtractive. It is ecological.” (18).

—————————————————————————————————————-

[i] An actual case, presumably reflecting the attitudes and assumptions of the department, which shall of course remain nameless. The decisions made were probably not calculated, nor are they unusual.

[ii] Designed specifically for illustrative purposes for this essay, using the commercial online survey utility Vovici EFM Feedback.

[iii] The same is true for this pupil in the following term. The implication may be that none of the teachers thought his deportment needed comment, but given the nature of their other remarks that seems unlikely.

[iv] In a quick and entirely unscientific experiment with the teenage members of this author’s household, even considerable curiosity about the subject of a photo did not prompt the examiner to turn it over.

—————————————————————————————————————-

Works cited:

Bolter, Jay David. Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2001. Print.

Calgary School Board. Report of the Progress, Attendance and Deportment of Student. 1920. Print.

Kress, Gunther. Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge, and learning. Computers and Composition 22 (2005): 5–22. Web. 6 Nov. 2009.

Postman, Neil. Technopoly: the Surrender of Culture to Technology. New York: Vintage Books, 1992. Print.

Sassoon, Rosemary. Handwriting of the Twentieth Century. London: Routledge, 1999. Web. 16 Dec. 2009.