By Lynnette Earle & Jerry Mah (access to Word Document)

Introduction

The invention of photography and its legacy has changed the world. Photography has modified the phenomenology of reading and writing by enhancing the text only experience. A brief history of this incredible invention will help to pave the road of understanding how it has influenced culture, how it has changed the face of simple text, how it can be used as both a research and storytelling tool, and how it is used in general education.

A Brief History of Photography

The optical principle, discovered by ancient Greeks, is the concept of “light passing through a tiny hole will produce an inverted image on a surface opposite the hole” (Friedman & Ross, 2003, p. 3). The same principle was used for the camera obscura (Latin for darkroom) which allowed for an image to be created, but not printed. The very first permanent image was developed in 1826 by French inventor Joseph Niépce (National Geographic Society, 2012). Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, inventor of photography, in 1838 made a remarkable discovery, using a combination of a silver plated sheet of copper and a chemical process, thus creating the daguerreotype camera (Daniel, 2004a). And in 1839 when Sir John Herschel “coined the term Photography deriving from the Greek “fos” meaning light and “grafo” – to write” (Tolmachev, 2010).

During the 1800’s there were many firsts for photography; 1839 – first photo of a person, 1845 – first photo of the sun, 1847 – first photo of lightning and war, 1850 – first positive photograph prints on paper, 1851 – wet plate process invented, 1858 – first bird’s-eye view photographs, etc. (National Geographic Society, 2012). In 1888, the beginning of photography as known today, began with the release of the first Kodak camera by George Eastman. Twelve years later in 1900, Kodak introduced the Brownie (a box camera with roll film), which sold for only a dollar (National Geographic Society, 2012). “As early as 1905, [Oskar Barnack] had the idea of reducing the negative format and enlarging the photographs at a later stage. He succeeded in turning this momentous idea into reality 10 years later… [when] he developed the Ur-Leica, arguably the first truly successful small-format camera in the world. The small picture format of 24x36mm was achieved at that time by doubling the 18 x 24 mm cinema format. The photographs created in 1914 were of outstanding quality for the time. Delayed due to WW1, the first Leica (a contraction of Leitz Camera) did not enter series production until 1924 and was introduced to the public in 1925” (Leica Camera AG, 2006). Later, in 1947, the Polaroid camera was invented by Edwin H. Land and released to the public in 1948 (National Geographic Society, 2012).

The dawn of the digital camera began in 1975 when Steven Sasson, an American electrical engineer who worked for Kodak, invented the world’s first digital camera, which was about the size of a toaster (National Geographic Society, 2012). From this point on, the digital camera has continued to change shape and evolve, essentially leading to the demise of Kodak itself. The shift that has occurred throughout the history of photography can be seen as a remediation, “in the sense that a newer medium takes the place of an older one, borrowing and reorganizing the characteristics of [photography] in the older medium and reforming its cultural space” (Bolter, 2001, p. 23). The digital camera of today is a remediation of what Daguerre invented in 1838 and will likely remediate into something new in the future.

[http://prezi.com/-dypfilcaail/history-of-photography/]

Photography’s Effect on Culture

Changes in the manufacturing of the printed book became a significant factor in introducing images. As indicated by Bolter (2011), this remediation from a print only culture altered how people interacted with books. Literacy became more than just writing; photographic images demanded new skills in understanding. This demand for new thought processes pertained not only to common people, but to academics as well. Fischman (2001) describes how early scholars dismissed the credibility of images, questioning their viability as sources of information. At the root of this issue, academics appeared to be conflicted in their self-confidence to interpret photographs.

Academics were not alone in this conflict. Although art enjoyed a close kinship and relationship to photography (Benjamin, 1972), there was conflict within the ranks of artists. Early photographers, many of whom were also artists using daguerreotypes as an aid for painting, were beginning to take on photography as a serious art form. This caused friction within the art community, with debate between traditionalists and innovators. Traditionalists holding ground on previously used mediums and innovators developing photography as a new medium; changing how art was interpreted. Wilkinson (1997) speaks to this decline in relations as a disagreement over “aesthetic consensus” (p. 23). Also driving this change was new technology in typography. These changes occurred through the use of minimal words, captions and bold images; ushering in a new age in print and images.

Transitioning from Text to Mixed Media

Malcom (2004b) indicates that the first printed book with photographs was Fox Talbot’s “The Pencil of Nature” using the calotype process in 1844. By using this book, Talbot was able to promote his patented calotype as a proof of concept. During this time period, Daguerre was also working on a different photographic process. Because Talbot’s process was patented and Daguerre’s was not, the daguerreotype became the more popular of the two.

As time progressed, so did changes that enabled photography’s popularity through ease of use and accessibility. According to Way (2006), the 1860s heralded the introduction of photography in newspapers. By the 1940s to 50s, books on photography were becoming prevalent, as was their status as a serious communication tool. Within the next decade, galleries and museums were starting to show photographs as desired art pieces, with universities offering classes on photography.

With both technological and cultural changes, people responded by learning in a different way. Through research, we can see how these visual images help with memory recall. Ong (2002) stated that photographs can serve as an “aides-mémoires” (p.85). In essence, Ong is suggesting that photographs have the ability to be utilized in a manner which symbolically represents multiple meanings, yet also encodes them for the user.

Due to technology’s ability to create changes in the world, photography would not remain as the sole visual medium. This process of remediation from text only, to the inclusion of pictures, would progress to the next step. MacDougall (2009) posits that stereographs were a necessary invention that helped bridge people between photography and cinema. MacDougall suggests that these complex images were able to convey the idea that photographs could take on new dimensions. As cinema started to take shape and gain in popularity, photography’s influence could still be seen in how early films were shot. MacDougall points to a certain “flatness” in early motion pictures; as if these emerging films were framed pictures with motion attached.

Photographs as Research Tools

It would not take too long before photography would become a serious tool in qualitative studies. Szto, Furman, and Langer (2005) point out how Lewis Hine was able to use photographs of children working in harsh factory conditions as a way to enact child protection laws. As a qualitative research tool, Schwartz (1989) reminds researchers to “…be grounded in the interactive context in which photographs acquire meaning” (p. 120). This refers to a common tendency towards ignoring the processes involved in interpreting and making meaning from images. By enabling a broader focus, researchers can gain a holistic view through a series of pictures. Schwartz indicates that the camera is an essential part of an ethnographer’s toolkit.

As a quantitative research tool, for example, photography has been used in research that focused on ethnic and gender differences, Wondergem and Friedlmeier (2012) examined smiles by analyzing yearbook photos. Prior research indicated that in general, women smiled more in photographs (Brennan-Parks, Goddard, Wilson, & Kinnear, 1991); however, ethnicity and age were not addressed. Wondergem and Friedlmeier’s (2012) research confirmed prior research, with girls smiling more than boys. In addition, they were able to extend research by determining that ethnic differences in smiling started to occur by grade eight. These differences only existed for boys, whereas no appreciable differences occurred with girls. In another example, Clancy and Dollinger (1993) concluded that women included more communal and connected pictures. Males on the other hand were more focused on pictures of physical activities and with their vehicles.

As a mixed methods tool, Margolis (2000) was able to gather quantitative and qualitative data by performing detailed analyses of class pictures. In this study, Margolis was able to identify changing class demographics by examining gender, and ethnicity. Other interesting elements were body language and possible indicators of socio-economic status through clothing and presentation. Also telling, were the lack of images noted by the author for certain classes and ethnicities during select time periods. Margolis speaks to the hidden agenda that classroom images sometimes portray; an example used was happy and well cared for Japanese students during their internment in relocation camps.

Photographs in Education

Photographs Tell A Story

Visual images have had a significant impact on learning. In today’s classroom, picture books are a primary tool in the introduction and development of literacy. Samuels (1970) suggests that books targeting students began as far back as the 1650s when Comenius’ Orbis Pictus was used to teach reading.

As students rise through each grade level, textbooks begin to become a common instructional tool. Because textbooks are a nearly ubiquitous tool in education, they are also significant in their ability to drive school curricula (Sleeter & Grant, 2010). As a learning tool, Hammond (1998) suggests that photographs within textbooks are an essential part of instructional design by making “textual information more palatable” (p. 57). By creating these visual learning hooks, text becomes more meaningful when anchored to an image. Photographs are also an important part of illustrating theories or instruction too difficult to describe by text and too detailed to be illustrated.

Despite the importance of photos to be included in textbook content, there is indifference or a lack of care towards how images are integrated. Masur (1998) suggests that mistakes might include; artists misidentified, images in the wrong orientation, and images from a different time period used to illustrate another. Masur contends that if errors such as these were to happen with written text, the textbooks in question would be considered failures. By taking the appropriate measures and precautions, publishers are able to avoid issues.

Hammond extends the need to create better awareness with publishers. Hammond stresses the importance of how photographs are selected, because of the unintentional “hidden curriculum” they may portray. For example, Sleeter and Grant (2010) determined through their study of fourteen social studies textbooks, that minorities were significantly underrepresented in the photographs chosen. With intentional selection, pictures chosen by publishers and educators can help bridge ethnic and cultural boundaries.

Photography in the Classroom

As mentioned in the previous section, photography is seen throughout literature and classroom instructional aids. According to Howard (1916), the use of pictures, images or photographs aid in making what is read a reality and “give a sense-impression of the literary situation through the eye” (p. 540). Howard adds that “Psychological experiments have proved that impressions received through the eye are, for most persons, far stronger than those received through any other sense avenue” (p. 540). Photography, especially today with its ease of use through digital images, is an invaluable tool for teachers to enliven a lesson. However, as Howard points out, these images are “too often neglected or ignored. Yet we all know from experience and observation that a child upon opening a new book will hurriedly turn its pages to find its pictures, and if none are found, the child in disappointment will lay the book aside as “dry” or uninteresting… Texts should be well illustrated, and teachers should be intent upon utilizing the whole teaching power of the illustrations” (1916, p. 542).

The subject taught does not matter, nor does it matter if the teacher is a photographer or not. Photography in the classroom is an excellent way to enhance a lesson. According to Way, “Teaching photography in art class or integrating photography into other disciplines can provide the types of engaging learning activities that both research and practice say are effective” (2006, p. 9). The key to a balanced education for students of today’s visual literacy explosion, is allowing for cross-curricular activities. FlixelPix, a landscape and reportage photographer, outlines in his blog that photography can be used in many subject areas, other than the obvious courses such as art, journalism, and social studies. Photography can also be used in mathematics courses by measuring or calculating symmetry, shutter speed fractions, aperture, the area of a circle, exposure time, and frame rate of moving images, as well as in science or physics courses by understanding how light works and calculating the focal length in photography (2010).

Empowering students with the ability to be active learners by providing them with a camera with which to take pictures has endless learning opportunities. Teachers should be allowing students “to appropriate digital photography and use it as a means to shift from their usual roles as restricted participants… and engage in sophisticated negotiations with their fellow students as photographic subjects and within the norms of classroom behavior” (Ching, Wang, Shih & Kedem, 2006, p. 366). Way (2006) suggests that by permitting students to become image-makers and -readers, they will learn pertinent communication and problem-solving skills in order to better navigate today’s progressively more challenging and visual culture. The use of photography in the classroom allows for both students and teachers to become more visually literate. Ching, Wang, Shih & Kedem (2006) conducted a study about a photo journal project which not only incorporated visual literacy skills, but promoted “student-centered and meaningful technology integration, and it also proved to be effective in promoting students’ reflections” (p. 368). Reflection through photography can be a powerful tool for students and teachers alike.

According to Moran and Tegano, “for teachers, photography is powerful in its ability to portray complex meanings and practical in the ease of manipulation of photographs as a language of inquiry” (2005, para. 15) which is both generative and constructive. By using photography in this manner, Moran and Tegano state that photography can be a powerful research tool in collaborative knowledge construction and a way to improve practice. It is clear that using photographic documentation as a record of student learning, but also as a way for teachers to create questions about their own teaching, will enhance the learning environment. This form of documentation becomes a conduit for creating teacher-student conversations in a metacognitive manner about the learning that has occurred (New, 1990, 2007).

Conclusion

Photography’s impact has been significant on culture, as a meaning making tool, and has greatly influenced the way we learn. Its ability to remediate print expanded the need for new literacies. Beginning with the ancient Greeks’ invention of the Camera Obscura to the modern processes introduced by Kodak, the art and science behind creating visual images has fully permeated our society. Our ability to tell stories, collect visual evidence, and to use it as a research and learning tool, has demonstrated the uniqueness of this medium. Photography has become an essential tool in our classrooms through providing visual literacy, enabling interdisciplinary connections, student collaboration in sophisticated tasks, and the documentation of learning. We have come to discover that photography is an essential part of our lives.

References

Benjamin, W. (1972). A short history of photography. Screen, 13(1), 5–26. doi:10.1093/screen/13.1.5

Bolter, J. D. (2011). Writing as technology. Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print (2nd ed., pp. 14–26). New York, NY: Routledge.

Brennan-Parks, K., Goddard, M., Wilson, A. E., & Kinnear, L. (1991). Sex differences in smiling as measured in a picture taking task. Sex Roles, 24(5), 375–382. doi:10.1007/BF00288310

Ching, C. C., Wang, X. C., Shih, M. L., & Kedem, Y. (2006). Digital photography and journals in a kindergarten-first-grade classroom: Toward meaningful technology integration in early childhood education. Early Education and Development, 17(3), 347–371. doi:10.1207/s15566935eed1703_3

Clancy, S. M., & Dollinger, S. J. (1993). Photographic depictions of the self: Gender and age differences in social connectedness. Sex Roles, 29(7), 477–495. doi:10.1007/BF00289322

Daniel, M. (2004a, October). Daguerre (1787–1851) and the Invention of Photography. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved from http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/dagu/hd_dagu.htm

Daniel, M. (2004b, October). William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877) and the Invention of Photography. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved from http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/tlbt/hd_tlbt.htm

Fischman, G. E. (2001). Reflections about images, visual culture, and educational research. Educational Researcher, 28–33.

Flixelpix. (2010, July 21). Six applications of photography in education. [weblog comment]. Retrieved from http://www.flixelpix.com/blog/six-applications-of-photography-in-education/

Friedman, A., & Ross, D. S. (2003). History of Photography. Mathematical Models in

Photographic Science, 3–6. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-55755-2_2

Hammond, J. D. (1998). Photography and the “Natives”: Examining the hidden curriculum of photographs in introductory anthropology texts. Visual Studies, 13(2), 57–73. doi:10.1080/14725869808583794

Howard, C. (1916). The use of pictures in teaching literature. The English Journal, 5(8), 539-543. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/800985

Leica Camera AG. (2006).Oskar Barnack: His genius revolutionized photography. Retrieved from http://en.leica-camera.com/culture/history/oskar_barnack/

MacDougall, D. (2009). Anthropology and the cinematic imagination. In C. Morton & E. Edwards (Eds.), Photography, Anthropology and History: Expanding the Frame. Ashgate Publishing Company.

Margolis, E. (2000). Class Pictures: Representations of Race, Gender and Ability in a Century of School Photography. education policy analysis archives, 8(31). Retrieved from http://epaa.asu.edu/ojs/article/download/422/545

Masur, L. P. (1998). “ Pictures Have Now Become a Necessity”: The Use of Images in American History Textbooks. The Journal of American History, 84(4), 1409–1424.

Mifflin, J. (2007). Visual archives in perspective: enlarging on historical medical photographs. American Archivist, 70(1), 32–69. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40294449

Moran, M. J. & Tegano, D. W. (2005). Moving toward visual literacy: photography as a language of teacher inquirí. Early Childhood Research & Practice, 7(1). Retrieved from http://ecrp.uiuc.edu/v7n1/moran.html

National Geographic Society. (Producer). (2012). National geographic image collection: History of photography. Retrieved from http://photography.nationalgeographic.com/photography/image-collection/

New, R. S. (1990). Projects and Provocations: Preschool Curriculum Ideas from Reggio Emilia, Italy. Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/contentdelivery/servlet/ERICServlet?accno=ED318565

New, R. S. (2007). Reggio Emilia as cultural activity theory in practice. Theory Into Practice, 46(1), 5–13. doi:10.1080/00405840709336543

Ong, W. J. (2002). Writing restructures consciousness. Orality and literacy (pp. 77–114). Routledge.

Samuels, S. J. (1970). Effects of pictures on learning to read, comprehension and attitudes. Review of Educational Research, 40(3), 397-407. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1169373?origin=JSTOR-pdf

Schwartz, D. (1989). Visual ethnography: Using photography in qualitative research. Qualitative Sociology, 12(2), 119–154. doi:10.1007/BF00988995

Sleeter, C. E., & Grant, A. (2010). Race, class, gender, and disability in current textbooks. In E. F. Provenzo, A. N. Shaver, & M. Bello (Eds.), The Textbook as Discourse: Sociocultural Dimensions of American Schoolbooks (pp. 183–215). New York, NY: Routledge.

Szto, P., Furman, R., & Langer, C. (2005). Poetry and Photography An Exploration into Expressive/Creative Qualitative Research. Qualitative Social Work, 4(2), 135–156. doi:10.1177/1473325005052390

Tolmachev, I. (2010, March 15). A History of Photography Part 1: The Beginning. Retrieved from http://photo.tutsplus.com/articles/history/a-history-of-photography-part-1-the-beginning/

Wall, C. (2008). Picturing an occupational identity: Images of teachers in careers and trade union publications 1940–2000. History of Education, 37(2), 317–340. doi:10.1080/00467600701878038

Way, C. (2006). Focus on photography: A curriculum guide. International Center of Photography, New York. Retrieved from http://www.quebecpress.com/pmcodes/fop.pdf

Wilkinson, H. (1997). “The New Heraldry”: Stock Photography, Visual Literacy, and Advertising in 1930s Britain. Journal of Design History, 10(1), 23–38. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1315946

Wondergem, T. R., & Friedlmeier, M. (2012). Gender and ethnic differences in smiling: A yearbook photographs analysis from kindergarten through 12th grade. Sex Roles, 1–9. doi:10.1007/s11199-012-0158-y

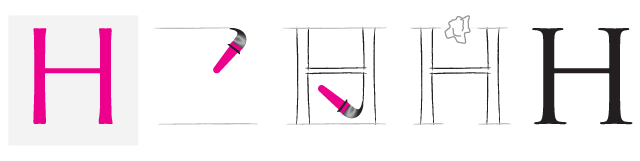

Features: Those elements that add the basic strokes of a letter: mainly serifs and terminals. (Bringhurst, 2004)

Features: Those elements that add the basic strokes of a letter: mainly serifs and terminals. (Bringhurst, 2004) x-height and width: The former is the height of the lowercase “x” measured from the baseline. This responds to the fact the the x is the only lowercase letter with relative evenness on its top and bottom. (Bringhurst, 2004) The latter stands for the horizontal proportion of the whole sign.

x-height and width: The former is the height of the lowercase “x” measured from the baseline. This responds to the fact the the x is the only lowercase letter with relative evenness on its top and bottom. (Bringhurst, 2004) The latter stands for the horizontal proportion of the whole sign.

A Moderate View

In Orality and Literacy, Ong (2002) presents an elaborate account of a well reasoned, and highly detailed, but polarizing description of the social and psychological consequences associated with technological determinism as it applies to literacy and literate culture. This account sets up a hierarchical structure that places literacy superior to orality. While he is easy to follow, fascinating, and insightful, Ong’s presentation is unsatisfying in its strong technological determinism and unnecessary hierarchical treatment of orality and literacy.

Ong (2002) neglects to discuss the possibility that literacy and orality can be complementary technologies. Indeed his consideration of orality as “natural” and writing as “artificial” (p. 82) suggests that he does not fundamentally consider speech as being technology in itself; however, in Chandler’s Biases of the Ear and Eye (1994), Josipocivi reminds us that, “to use language at all is to use an instrument which is forged by others… that is to say… It is never my language, for ‘I’ have no language.” Arguably then, oral language must be a technology, and since it has not gone out of use with the advent of written language, then it must serve some useful purpose and be complementary to written language. Chandler (1994) presents a list of dichotomies between the spoken and written word that illustrate some complimentary purposes. These dichotomies include being fluid versus fixed, rhythmic versus ordered, subjective versus objective, resonant versus abstract, present versus timeless, participatory versus detached and communal versus individual. Each attribute here being neither positive nor negative but is useful in context.

Ong’s discussion of orality as natural and writing as artificial (1967) is further problematic in that he makes the argument by describing the “most arduous discipline” required to learn to write and glibly claiming that human that is physiologically and psychologically capable will learn to speak. This implies that learning to speak is not so arduous, yet there is evidence to the contrary that it is and it comes from the experience of parents. Most parents will not hesitate to agree that their children can understand much oral language long before they are able to speak it, but there is a lag between the time a child is psychologically able to understand oral language and when they can produce it even though the physiological change in that time is minimal. Furthermore, a child who learns baby sign language is often able to use this language long before they can use oral language. These parental experiences involving babies who are able to understand and produce language before they are able to speak gives evidence that speaking is more arduous than Ong would have one believe.

If orality and literacy are both technologies, then consideration of them as complimentary can be given. A complimentary relationship demands that one is not subordinate to the other and that each serves a different purpose, but with a common intent. While it may seem that literacy is a natural progression from orality and even that orality is a necessary condition for literacy, the mere existence of literate people who are mute and hard of hearing dispels that myth. It is possible to be literate without being oral or even aural, and so orality is not inferior to literacy. Furthermore, Ong himself (1982) brings attention to the fact that relatively few languages have developed literacy and those that have, do not forsake orailty. Both orality and literacy serve to express human thought. They are subordinate to it and they have the common intent to express thought, which they do complimentarily through the dichotomies described earlier.

The subordination of orality and literacy to thought reverses the direction of control in the technological determinism described by Ong, yet a complete pendulum shift to humanism would go too far as well. This is illustrated in the tendencies of many people who “speak before they think.”

Such detached and polarized theories as these may be used to attempt to understand what is not necessarily well-definable, but are not particularly accurate in describing the complexities and nuances of reality. A more accurate theory to describe the ways in which we use language is likely to resemble Chandler’s (1995) description of moderate Whorfians that accounts for a two-way interaction between thought and language and also emphasizes the importance of social context.

Chandler, Daniel (1994): Biases of the Ear and Eye: “Great Divide” Theories, Phonocentrism, Graphocentrism & Logocentrism [Online] U Retrieved from: http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/litoral/litoral.

Chandler, Daniel (1995): Technological or Media Determinism [Online] Retrieved from: http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/tecdet/tecdet.html

Ong, Walter (1967): The Presence of the Word: Some Prolegomena for Cultural and Religious History. New York: Simon & Schuster

Ong, Walter. (1982.) Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Methuen.