Postman (1992) suggested that technology is both a burden and a blessing. The Internet is a prime example of a technology that has benefits and drawbacks. While the Internet has vast amounts of information on any given topic, access is not universal or equitable, and its contents can be overwhelming to the uninformed user.

Information Overload

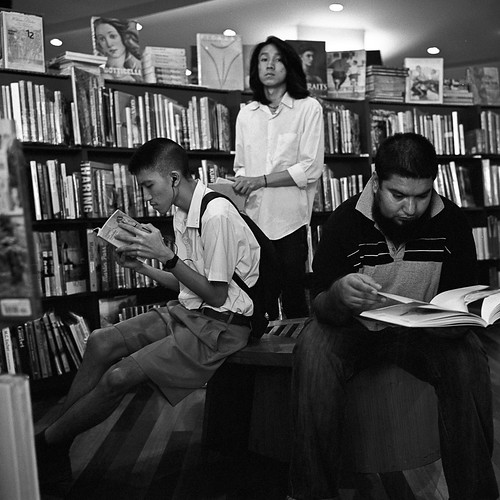

Today’s students have been labeled digital natives (Prensky, 2001), and Oblinger & Oblinger (2005) noted that those born after 1980 have attributes including increased digital aptitude and better multi-tasking abilities (as cited in Corrin, Lockyer & Bennett, 2010) which are the result of using computers, video games and the Internet for their entire lives (Prensky, 2001). Does this mean that digital natives are savvy at navigating the Internet?

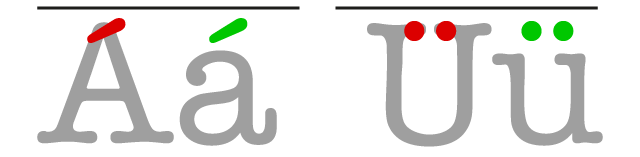

The authors of a study on student technology use concluded that there was a “disparity between actual level[s] of technology ability and use” (Corrin, Lockyer & Bennett, 2010, p. 397). In another study, Paryek, Sachs and Schossböck (2011) noted that study participants had difficulty finding information on the Internet, and concluded that “measures to enhance the Internet competence of teenagers are crucial” (p. 170). Two researchers have even gone so far as to refer to this situation as a second digital divide that “includes differences in skills to use the Internet” (van Deursen & van Dijk, 2011, p. 908).

With approximately one trillion web pages (Farhan, D’Agostino & Worthington, 2012), an Internet user must discern what information is credible and what is not. Where does a user obtain the skills to differentiate between sites containing accurate information versus someone’s blog? The situation is akin to the suggestion by Thamus that a new invention, in this case the Internet, would create readers who “will receive a quantity of information without proper instruction” (as cited in Postman, 1992, p. 16). Students are usually somewhat successful in locating information on a particular topic, but many are not sure what to do with it or how to organize it, which can sometimes lead to plagiarism.

Some students are guilty of copying and pasting information directly from a website, adding some of their own words and submitting it as their own work. Plagiarism, however, is not a new problem. Ong (1982) noted that “with writing, resentment at plagiarism begins to develop” (p. 129) and the poet Martial, 38-41CE to 104 CE (Martial, 2003) used the Latin word plagiarius to describe an individual “who appropriates another’s writing” (Ong, 1982, p. 129). Perhaps the problem, as identified in a study by Power (2009), is that students “lack the ability to tell the difference between quoting, citing and paraphrasing” (p. 650) especially when dealing with the vast amount of electronic information available on the Internet. If this finding is indicative of all students, then educators must find new ways to ensure that all students receive “proper instruction” on how to gather and summarize resources obtained from the Internet (Postman, 1992, p. 16).

In his book, Postman (1992) postulated that “schools teach their children to operate computerized systems instead of teaching things that are more valuable” (p. 11). However, the Ontario curriculum advocates a more balanced approach than Postman suggested. For example, the Business Studies curriculum for senior high school students stipulates that “students develop critical thinking skills, and strategies required to conduct research and inquiry and communicate findings accurately, ethically and effectively” (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2006, p. 4). Proper use of the Internet requires students to apply their analytical skills in locating appropriate and relevant information.

Digital Divide

Postman (1992) asserted that “the benefits and deficits of a new technology are not distributed equally” (p. 9) and this reference can be applied to Internet access. Despite the fact that the number of Internet users in developing countries doubled between 2007 and 2011, only one-quarter of the developing world was online at the end of 2011 (International Telecommunication Union, 2012). In addition, 70% of households in the developed world had Internet access versus only 20% in the developing world (International Telecommunication Union, 2012).

This digital divide is also evident in Canada as the availability of quick and reliable Internet access is often dependent on whether you live in an urban or rural area. Marlow and McNish (2010) suggested that broadband access would result in an economic growth rate of 1.2% for every 10% increase in broadband availability. A research director at Harvard quipped that broadband is “essential infrastructure for competitive nations” and suggested that communities without such access would be at a competitive disadvantage (Marlow & McTish, 2010, para. 12). Evidently, the benefits of high-speed Internet access are being enjoyed by Canada’s urban population, while its rural residents struggle with slow and often unreliable access; a perfect illustration of Postman’s prediction about the inequitable distribution of a new technology’s benefits and drawbacks.

Conclusion

It is unlikely that Postman could have imagined the proliferation and worldwide acceptance of the Internet back in 1992, but his predictions about the unequal distribution of the advantages and disadvantages of this technology were accurate and are occurring within Canadian borders. In addition, the massive amount of information available on the Internet places an additional burden on educators to ensure that students are adequately equipped to navigate the complex world of the Internet. Hopefully educators can rise to the challenge.

References

Corrin, L., Lockyer, L., & Bennett, S. (2010). Technology diversity: An investigation of students’ technology use in everyday life and academic study. Learning Media and Technology, 35(4), 387-401. doi:10.1080/17439884.2010.531024

Farhan, H., D’Agostino, D., & Worthington, H. (2012, September 5). Web index 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2012 from http://thewebindex.org/2012/09/2012-Web-Index-Key-Findings.pdf

International Telecommunication Union. (2012, June). Key statistical highlights: ITU data release June 2012. Retrieved September 17, 2012 from http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/ict/statistics/material/pdf/2011%20Statistical%20highlights_June_2012.pdf

Marlow, I. & McNish, J. (2010). Canada’s digital divide. Retrieved September 17, 2012 from http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/canadas-digital-divide/article4313761/?page=1

Martial. (2003). Martial select epigrams. L. Watson & P. Watson (Ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Ong, W.J. (1982). Orality and literacy. London: Routledge.

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2006). The Ontario curriculum grades 11 & 12 (revised): Business studies. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/secondary/business1112currb.pdf

Paryek, P., Sachs, M., & Schossböck, J. (2011). Digital divide among youth: Socio-cultural factors and implications. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 8(3), 161-171. doi:10.1108/17415651111165393

Postman, N. (1992). Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. New York: Vintage Books.

Power, L. (2009). University students’ perceptions of plagiarism. The Journal of Higher Education, 80(6), 643-662. doi:10.1353/jhe.0.0073

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants part I. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1-6. doi:10.1108/10748120110424816

van Deursen, A. & van Dijk, J. (2011). Internet skills and the digital divide. New Media Society, 13(6), 893-911. doi:10.1177/1461444810386774

The Power of Powerful Words

Sunday after Sunday I sit in my pew and listen, sometimes distantly, as the priest pronounces great truths and wisdom from the pulpit. Nobody else speaks; nobody questions what is said; nobody challenges the Word. According to O’Donnell (1999), my weekend rituals, as well as my sense of morality, are governed by the chance occurrence that early Christians transcribed their beliefs to avoid persecution. The power of Words, whether they be written or spoken, is undeniable. Words have the ability to build ideas and peoples up, or break them down and scatter them about. Postman (1992), in discussing Thamus’ error of omission, states that “writing is not a neutral technology whose good or harm depends on the uses made of it.” In reality, writing is the one true technology that has changed everything for humans: how we learn, how we remember, how we create, how we communicate, how we love and how we hate. Words, simple words, have changed everything.

As Ong (1982) writes, “sound cannot be sounding without the use of power.” Everyone stops to listen to the person speaking; crowds are fearful of interrupting the powerful leader, sharing insight with the humble masses. Of course, as Stan Lee (1962) put it so simply “With great power comes great responsibility.” Those who command the Words on which the masses hang their hopes must be careful and vigilant to use their authority for positive gains, and not for selfish concerns. As Postman (1992) points out, “the benefits and deficits of a new technology are not distributed equally.” There will always be those in the inner circle, charged with distributing the Words to those on the outside. The imbalance in power, wherein so much is given to so few, necessitates that those in control should be carefully and thoughtfully selected to ensure that they are indeed worthy of the role. Salespeople, tour-guides, teachers, judges, priests, political leaders and countless other professions and occupations all carry the same weight and responsibility of doing what it morally and socially correct with the information at their disposal and authoritarian figure they hold in their respective arenas.

In the 2010 film The Book of Eli, Carnegie, played by Gary Oldman, is relentless in his pursuit of a book. Set against the backdrop of a post-apocalyptic wasteland, the most invaluable tool, the most destructive and coercive weapon is a book: a Bible. Realizing that, in a world wherein perhaps hope is the most valuable commodity, Carnegie states that “People will do whatever I tell them, if the words are from the Book. It’s happened before, it’ll happen again.” Powerful Words have the potential to uplift, motivate, even save those who have nothing else. If those who claim to represent the Words are themselves untrustworthy, they may of course use the Words for their own repellant needs and wants.

If, as McLuhan (1964) coined that “the medium is the message, Thamus, as Postman (1992) explains, is correct in being “concerned not with what people will write; he is concerned that people will write.” (p.7) In this instance, I’m not sure I can agree. While a bruise caused by a stone or stick will heal in time, Words, especially when written, can be much more damaging and hurtful. As Ong discusses, spoken words exist for only a few seconds before they disappear out of existence. Written words however, are committed to the page, existing in a physical form, to be preserved and saved for future generations. While I do not refute that it’s important that we, as a literate society, are able to write, it is also equally important what is being written. An elementary school students can get over being called a name much more quickly than a high school student being written about on a taunting website. It is important, as an elementary school teacher that my students understand immediately the power of the Words they choose to use. Our classroom project of creating Student Blogs will help to show the impact their Words can have on others as well as their permanence effect as their work will be available for, potentially, the entire planet to read.

As Ong (1982) so eloquently phrases, “writing was and is the most momentous of all human technological inventions.” (p. 84). There is an interesting duality that exists with Words. Spoken aloud, Words are much more easily questioned. Written down, Words are regarded as unblemished truth and wisdom. They are permanent, important, and meaningful. People are very slow and wary to question what they read, but will quickly and easily dismiss conversations as gossip or hearsay. When Words are printed on a medium, they become undeniable, permanent, and powerful. They transcend thought and emotion to the realm of physical creation.

References:

Whitta, G. (Writter), & Hughes Brothers (Directors). (2010). The Book of Eli [Motion Picture]. United States, Warner Bros. Pictures Distribution

O’Donnell, J. & Engell, J. (1999). From Paper to Papyrus. Cambridge Forum

Postman, N. (1992.) Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. New York: Vintage Books.

Ong. Walter. (1982.) Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Methuen.

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding Media: The extensions of man. McGraw-Hill

Lee. S. (1962). Amazing Fantasy 1(15) Marvel Comics.