What’s an unappealing colour that you can think of? The first colour that I thought of was brown. To me, it looks like combination of unwanted colours and reminds me of dirt. However, this colour is highly associated with what makes our food look delicious.

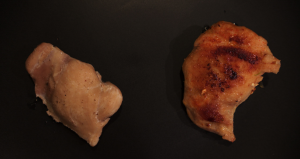

Now, which of the two would look more appetizing: a pale piece of chicken (cooked by boiling in water) or chicken that has been grilled until it is golden brown in colour? I think we would agree the second one is a better choice. So what is the cause of this difference in appearance?

A contrast between boiled chicken and grilled chicken

(Source: Myself)

The Maillard reaction

The Maillard reaction is a chemical reaction responsible for releasing flavours and aromas of food, while also browning them. Since most people only notice the colour change, it is also commonly known as the browning reaction! The process works by rearranging amino acids (the building blocks of protein) with sugars, and only occurs in temperatures of 140°C or higher. Usually proteins are coiled-up structures but when there is enough heat, denaturation (the unfolding of amino acids) happens, which is how the sugars are able to combine with them.

The Maillard reaction occurs in many foods, but have you noticed that they don’t all have the same flavour? Coffee and popcorn both experience the same reaction, but coffee has a nutty flavour while popcorn has a biscuit flavour. This is because of the different kinds of amino acids, as each kind of amino acid releases a different scent and flavour.

Why don’t we just cook on high heat all the time?

Although the Maillard reaction is highly desired, we can’t just cook on high heat all the time. This is because another reaction takes place when the temperature is too high: burning. This reaction gives an unwanted bitter flavour.

However, there is a way to increase the rate of the Maillard reaction. Because water boils at 100°C, lowering the moisture content on the surface of your food will promote the Maillard reaction. This helps keep the meat at a higher temperature since it no longer limited by the temperature’s boiling point.

Didn’t you just describe caramelization?

Many people confuse the Maillard reaction with caramelization. Although they are both browning reactions, they are different reactions. Caramelization is the burning of sugar, and as a result, it occurs in temperatures above the Maillard reaction. The results of the two reactions look similar but the key difference is that caramelization breaks down the sugar, rather than recombine them, and does not require amino acids.

Caramelized sugar on ice cream

(Source: Myself)

The Maillard reaction is the reason why our food is so appetizing, but is under-appreciated. Many people who cook know through experience that higher heats will give a nice colour to the food, but do not know that it is actually adding flavour too.

To learn more about how the Maillard reaction works, watch this video.