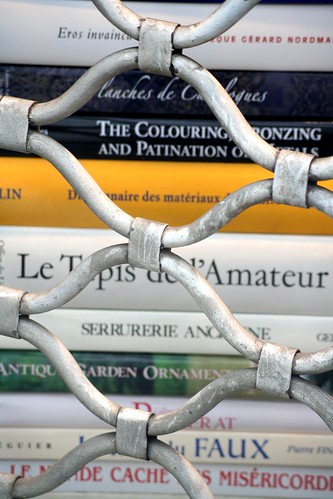

The basal reader has been seen an invaluable tool in reading to many teachers for over a century. The reader has undergone a few changes, but the basic premise remains the same. Students read leveled books that prepare them for grade level examinations and curriculum. Teachers are not to deviate from these readers when teaching reading comprehension, though this is not always the consensus in the education community. “Reading is seen as a flexible tool for learning rather than an inflexible set of skills to be acquired, stored, and brought out for use as the situation arises” (Harste, 2001, p.265). As Harste states, this is the viewpoint by most teachers on basal readers in education today. In this paper, I will first give a brief history of the introduction and usage of basal readers, followed by an overview of the changes to education as a result of this technology.

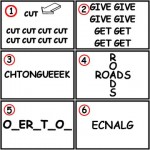

Basal readers were introduced to school children in the mid-to-late 19th century. It was during this time that students would congregate into one room schools, where the ages would range from 5 to 18, to be taught by one teacher. There were very little textbooks available during this time. One teacher, William McGuffey, was asked to create a series of books for primary students. Known as McGuffey Readers, they were filled with stories of strength, character, goodness and truth. These primary books contained many pictures and followed a phonics based approach to teach reading. Over time, readers were then created for older students, which focused more on skills in oral reading and presentation. The readers for older students contained poems, stories, and bible passages. Another known basal reader is the Dick and Jane series, written by William S. Gray in the 1930s. These readers focused more on reading the whole word and with using repetition and did not follow the same phonics lessons the McGuffey readers did. The modern day basal reader used from about the 1950s onwards, has books for students, a guide for the teacher, as well as some predetermined activities (Hoffman, McCarthey, Elliott, Bayles, Price & Ferree, 1998). When working with basal readers, students are divided into groups “…according to their abilities to read accurately and to complete written assignments successfully” (Shannon, 2001, p.235). These skill based books/activities are taught in sequential order, with the teacher providing pre- and post- reading activities.

For much of the 20th century, teachers relied on basal readers to fulfill requirements for the reading comprehension curriculum. It was in the late 1970s that the pendulum shifted away from basal readers and workbooks to trade books and “experimental programs”. Goodman (2001) used both basals and trade books in her reading program and asked her students for feedback at the end of the year. She notes that her students “…were vehemently opposed to basals, almost all with the same reason: Basal readers are ‘boring’” (Goodman, p.277). Early basals, such as the Dick and Jane series, were criticized for their lack of diversity in the choice of characters and in storylines. “…The researchers suggest that the meaningless stories of beginning basal anthologies pose serious problems for young children. As as result, those students experience difficulty in learning to read” (Shannon, 2001, p. 237). In an infamous 1955 book, Why Johnny Can’t Read, author Rudolf Flesch criticizes the methodology of these readers. The whole word approach had students stumped when they came across a word they didn’t know when reading. The student was not versed in the phonics approach, since teachers were not supposed to deviate from the basal reading program, and overall literacy was declining. Flesch advocated for a return to the phonics approach, though it was many years after this book was published before schools began to do so.

At first, the basal reader was an excellent addition to education. It solved the dilemma of how to teach multiple ages and levels under one roof. As schools became bigger and there were more teachers, the lack of anything different kept the basal reader in circulation. The only change came with the readers of the 1930s, which had students reading whole words and not using a phonics approach. This resulted in many students scoring lower on literacy tests and a large number of students showing an overall disinterest in books and reading. Educational advocates went back to the phonics approach with great success, though it was not until quite recently that teachers started to try using trade books and activities other than basal ones. Harste’s (2001) research shows that “…almost anything teachers do beyond a basal reading program significantly improves reading comprehension” (p.265). Based on Flesch and Harste’s research, one might conclude that basal readers hindered progress in literacy for many years. “The basal sequence is so instruction-intensive that, by the end of the year, only one fourth grader had completed the fourth grade book. Instead of providing access to reading, the basal denies it” (Goodman, 2001, p.275-276). Teachers who had been taught with basals, continued to use them, unknowingly retarding reading skills for generations.

When speaking with fellow educational professionals, many share the sentiment that basal readers are outdated. “Advocates argue that basals have not lived up to their original promise to remain on the cutting edge of educational science in order to ensure that all students will learn to read” (Shannon, 2001, p.236). Many feel that using a varied approach will instead increase the literacy levels of their students. “…Through daily writing and reading and sharing they begin to recognize and remember words and their speaking vocabulary increases their reading vocabulary daily at a much faster rate than any basal reader could ever do” ( Oxendine, 1989, p. 12). Using a basal reading program, children must make the “…transition from ‘learning to read’ to ‘reading to learn’…” (Walsh, 2003, p.24). Walsh continues to argue that children are not gaining or extracting meaning from the text and the basal reader is merely a place where children learn to sound out words.

As an elementary school teacher, it is hard not to imagine a time without basal readers influencing reading comprehension lesson plans. Many generations of readers were the result of an implemented basal reading program. This program was not all bad, but it did not provide a variety in teaching methods, as many teachers did not deviate from the program manual. In the past 20 years, basal readers have seen a decline within the classroom. Teachers are choosing a varied approach when teaching reading skills, including a phonics component, using trade books, and having students create their own stories to read aloud. This approach has students more interested in reading, as well as using reading skills to learn new tasks in other subjects.

References

Flesch, R. Why Johnny Can’t Read–and what you can do about it. New York, Harper: 1955.

Harste, J. (1989, September). The Basalization of American Reading Instruction: One Researcher Responds. Theory Into Practice, 28(4), 265. Retrieved September 17, 2009, from Academic Search Complete database.

Hoffman, J., McCarthey, S., Elliott, B., Bayles, D., Price, D., Ferree, A., et al. (1998, April). The literature-based basals in first-grade classrooms: Savior, Satan, or same-old, same-old?. Reading Research Quarterly, 33(2), 168. Retrieved September 17, 2009, from Academic Search Complete database.

Oxendine, L., & Appalachia Educational Lab., C. (1989). Dick and Jane Are Dead: Basal Reader Takes a Back Seat to Student Writings. http://search.ebscohost.com

Shannon, P. (1989, September). Basal Readers: Three Perspectives. Theory Into Practice, 28(4), 235. Retrieved September 17, 2009, from Academic Search Complete database.

Walsh, K. (2003). Basal Readers: The Lost Opportunity To Build the Knowledge that Propels Comprehension. American Educator, 27(1), 24-27.