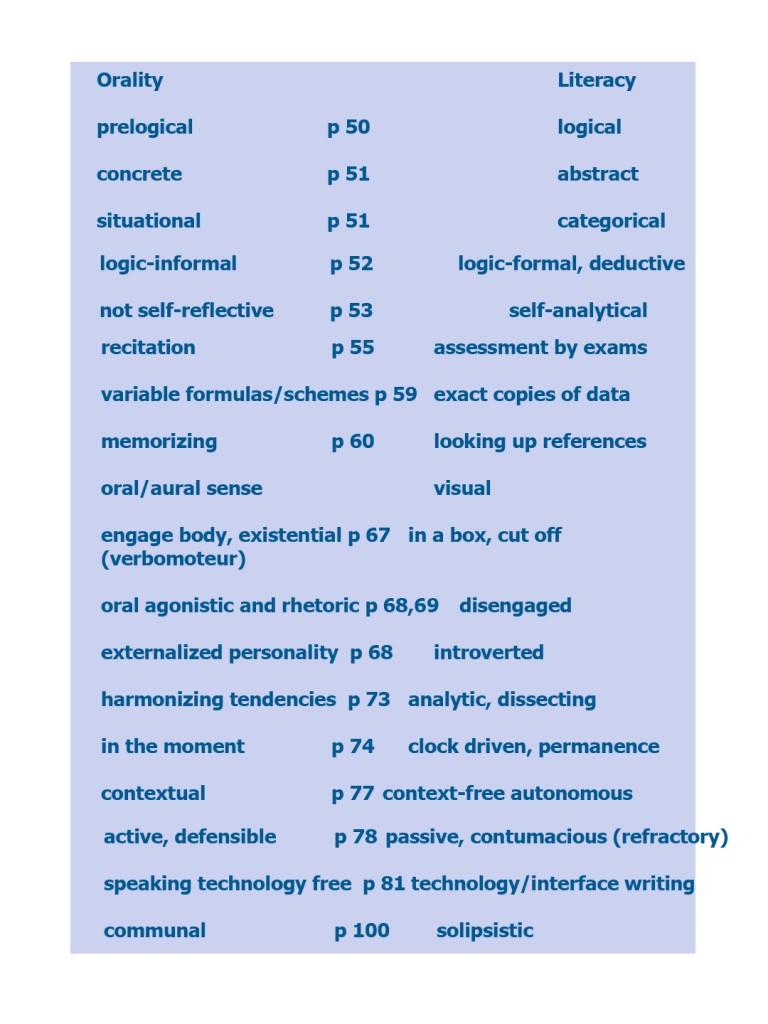

In the third and fourth chapters of Orality and Literacy, Walter Ong compares characteristics of orality and literacy, showing how consciousness is dramatically changed – “restructured” – by literacy. In exploring this transformation, though, he appears to miss the full significance of the confluence of several of the changes he describes.

Ong examines orality and literacy in relation to a variety of psychodynamics of orality, characteristics of thought and expression. He shows how oral story forms differ from literate in style and structure; the types of knowledge, and conceptualization that each favours. He further explores differences in use of memory between orality and literacy; in what is remembered, and how.

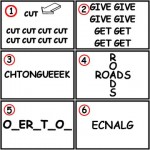

Against this extensive background he looks at research on early textual works based on oral creations (Milman Parry on the Iliad and the Odyssey; qtd. in Ong: 58), and more recent work with living narrative poets in Yugoslavia (Albert Lord; qtd. in Ong: 59), and concludes that oral memory works quite differently than literate memory: the “fixed materials in the bard’s memory are a float of themes and formulas out of which all stories are variously built” (60). He contrasts use of such formulaic elements with the methods and expectations of literate people memorizing from text, and writes at length about differences between orality and literacy with respect to the possibility of “stable” repetition or reproduction, and makes the point that even the idea of faithful reproduction differs between the two.

Ong relates that Lord, in his work with the Yugoslavian bards, found that “[l]earning to read and write disables the oral poet . . . it introduces into his mind the concept of a text as controlling the narrative…” (59) This was in reference to the process of oral composing, but it reflects the fact that oral narrative is by nature fluid, that variations in the story between tellers are part of the evolution of the culture and the form.

Such variations reflect the unique storyteller, the audience and the circumstances of the telling; the unvarying essentials reflect the needs and beliefs of the group or culture. “Originality”, Ong writes, “consists not in the introduction of new materials but in fitting the traditional materials effectively into each individual, unique situation and/or audience” (60). Ownership of the essential story in oral culture is communal; restrictions on how a story is told or used, by and to whom, in what season or context, arise from – and belong to – the story, the community and the culture.

This creates a world in which neither the storyteller nor the listener exists in isolation; they are dependent each on the other, partners in shaping and perpetuating narrative. The Okanagan author Jeanette Armstrong writes that “I am a listener to the language’s stories, and when my words form I am merely retelling the same stories in different patterns” (qtd. in King: 2).

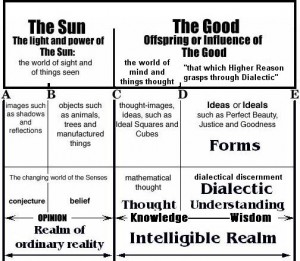

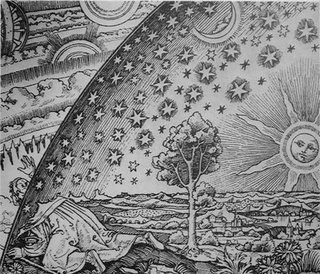

All this serves as the groundwork for a detailed examination of how consciousness itself is restructured in a literate world. The effects are profound. Language, through text, becomes external – “detached from its author” (78); as such it is “context-free” or “autonomous” (Ong references the work of E.D Hirsch and David R. Olson respectively; 79) and becomes irrefutable, unresponsive, and altogether unaccountable – as Ong delightfully says “inherently contumacious” (79). It is now mediated, requiring tools (and propagating technologies)… it precipitates a fundamental shift in the human awareness of self in place, and in time; and it greatly increases the potential for restriction of access to knowledge and dissemination of ideas.

Tucked among this survey of shifts in human consciousness and culture Ong mentions the potential for private ownership of words, noting that “typography had made the word into a commodity” (131), and acknowledges that it was a boon to the increasingly individualistic nature of human consciousness, and the growing tendency to perceive “interior . . .resources as thing-like, impersonal” (132).

Unfortunately, he pursues this idea no further, and so overlooks one of its most significant implications. It seems that he knows it well subconsciously, yet while it informs his entire work he doesn’t actually address its implications explicitly. The process of transferring “memory” outside the mind paradoxically makes story both external to the thinker and external to the community. Ong has already observed that “[p]rimary orality fosters personality structures that in certain ways are more communal and externalized, and less introspective than those common among literates” (69). But he stops short of recognizing the full consequences of this particular psychodynamic – and sociodynamic – shift: that literacy makes possible both the private ownership of knowledge and the knowledge of private ownership in a way never before imaginable.

In an oral culture, knowledge, once shared, was ‘common’; if ‘protected’, was secret. While knowledge had currency, and rules or custom or interests might determine what was told to whom, by whom, and when, its commodification in the modern sense was impossible. Like the Kiowa grandmother in N. Scott Momaday’s novel House Made of Dawn, oral peoples knew that words “were beyond price; they could neither be bought nor sold” (85). Knowledge could not be packaged for sale, nor last year’s knowledge devalued and replaced – at a price – with this year’s.

Private ownership of land and resources is likewise enabled by literacy; being dependent on the ability to demonstrate and enforce possession. The ability to create, delineate, and enforce ownership through what are essentially ‘text acts’ allows relations of ownership to take place at a distance; removes the need for physical demarcation and presence. Physical possession is no longer nine-tenths of the law. And in a literate world, the two can be combined: knowledge can be owned, controlled, traded, suppressed, or disseminated even by those who can not create it themselves.

Ong apparently does not appreciate the broader sociodynamic implications of literacy in relation to the existence of textual knowledge as a commodity. Ironically, the money he earns for his publisher is a manifestation of what Ong overlooked.

Works Cited

King, Thomas. The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative. Toronto: House of Anansi, 2003.

Momaday, N. Scott. House Made of Dawn. New York: HarperPerennial, 1999.

Ong, Walter. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London: Methuen, 1983.