In today’s century, as we discuss digital literacy, internet literacy, media literacy, and even television literacy (Rosen, 2009); it is clear that literacy is developing new accents that have become difficult to define in a few words. Rosen (2009) stated that “if we expect our children to be competent citizens, compete in the workplace, and lead productive lives, educators and parents need to plant the seeds of media literacy early in the educational arena” (p. 177). The iGeneration (Rosen, 2009) can access information instantly so educators have to find new ways to interact with their digital native students (Prensky, 2010).

Multimodal Modes of Representation and Digital Literacy

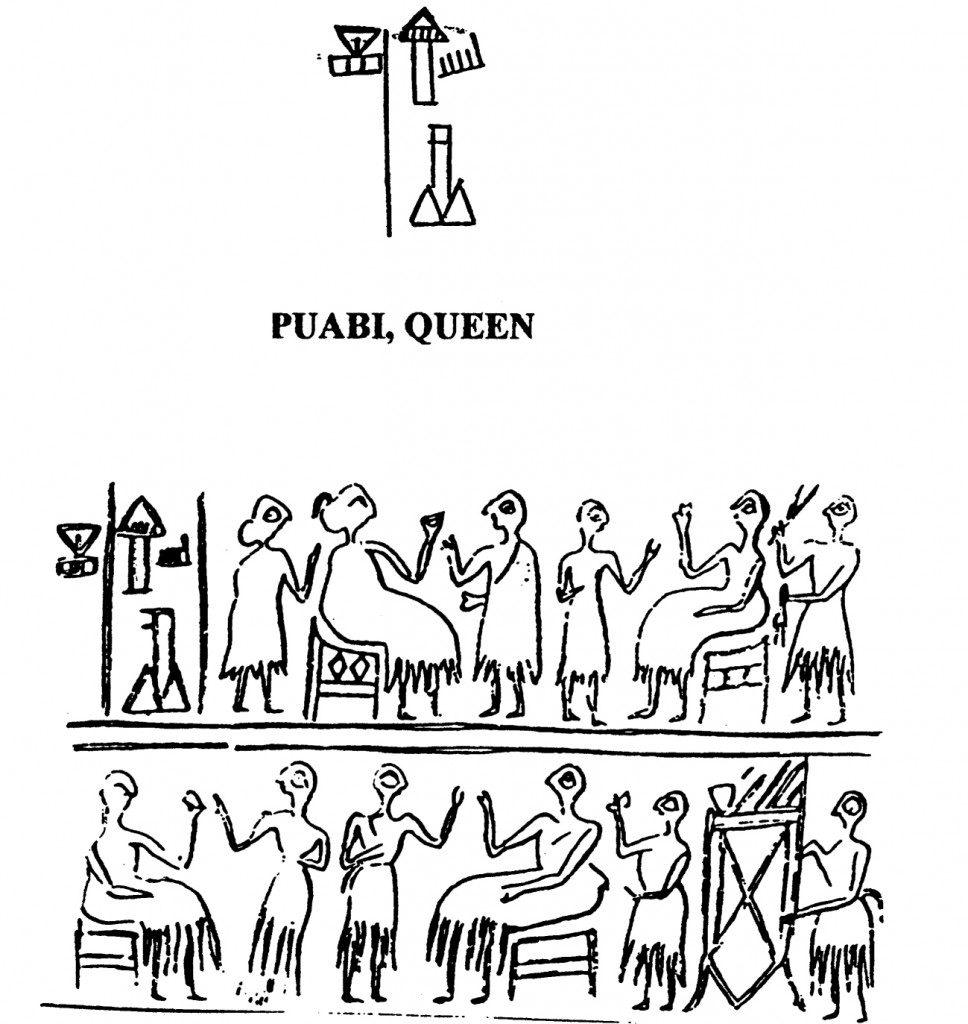

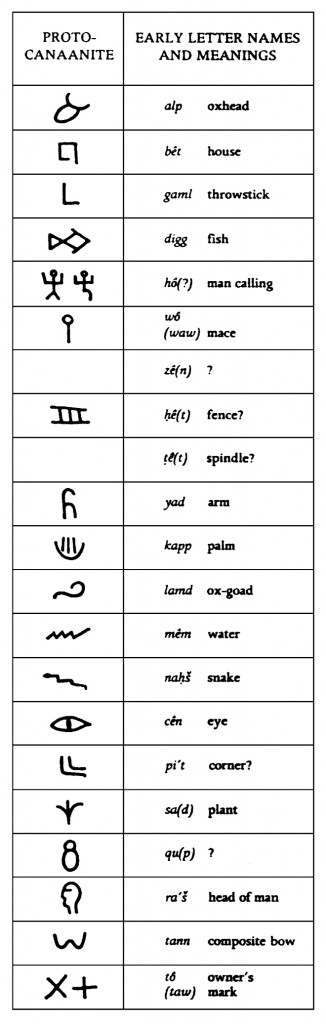

Visual modes of representation were used since the age of primary oral cultures (Ong, 2002). However, we are now using visual modes of representation within other modes of representation to present information and to communicate better. In the early primary oral cultures, written forms of communication, often just visuals (e.g., hieroglyphs), were used to keep valuable information. Indeed, since our developed societies are becoming more literate, the textual modes of representation may be more utilized; but combined with the visual modes of representation it certainly enforced messages.

Despite their use, multimodal modes of representation can be seen as a revolution. Hence, Kress (2005) suggested that their use has caused two kinds of revolution; “of the modes of representation on the one hand, from the centrality of writing to the increasing significance of image; and of the media of dissemination on the other, from the centrality of the medium of the book to the medium of the screen” (p. 6). In fact, in order for people to better understand the world, “the medium of the screen” has been used in multiple forms over the last century and is now part of our contemporary cultures.

Therefore, multimodal modes of representation found in digital technologies have extended our view of literacy. Dobson and Willinsky (2009) stated that the uses of computer and word processing as well as the rise of Internet and hypertext have ensured “the emergence of digital literacy” (p. 2). Likewise, using multimodal modes of representation in education signifies that, with the diversity of needs and learning styles, more students will be reached; hence, it should enable them to enter the workforce more successfully.

Students’ Diversity of Needs and Learning Styles: A Reality in Education

Further, some individuals are more at ease with “the immediacy of the picture to the mediation of the code in our search of a tangible, ‘real’ reference that would render the sing transparent” (Bolter, 2001, p. 57). In addition, Bolter (2001) suggested that viewers examining a picture will determine its significance without having any written text by it (p. 59).

Interestingly, over the years, I have noticed that the visual modes of representation had an effect on some students’ interest at reading a text, or, for instance, at participating in a discussion forum. In particular, it was noticeable how boys responded to visual modes of representation in contrast with girls. Hence, it was evident enough to change and use multimodal modes of representation like pictures, videos and hyperlinks along with the reflection questions. Indeed, boys’ participation changed instantaneously; really, “a significant digital divide in regards to gender” (Dobson & Willinsky, 2009, p. 13) was observed in relation with how at ease males can be with computers compared to females.

Nevertheless the fact that learning styles differ within the student’s population, and perhaps within genders, learning for some students with special needs can mostly occur with the help of visual modes of representation. There is still a lot to be investigated in this area but it is encouraging seeing that some students can now access knowledge according to their capacity and/or potential by using the proper digital technology, a fact that would not have been possible with print texts or textual modes of representation alone.

Living Life With Technology

Photo retrieved from http://www.flickr.com/photos/21468527@N07/2085259044/

The 21st Century Working Place

As the 21st century working place is largely looking for digital skilled employees who can collaborate and exchange ideas on a daily basis using digital technologies, it is critical that educators reshape their pedagogy, “a pedagogy that opens possibilities for greater access” (The New London Group, 1996, p. 72) and where no one should be left behind.

Even though the working place is not always accessible to all, it is the parents and the educators’ responsibility to provide students the digital skills they need in order to enter the workforce; for instance, by enforcing placements in the working place where students can develop and reinforce their abilities. Hence, schools have the obligation to prepare all students for the working life; digital technologies should help students with particular needs (e.g., students whose condition might impair them physically) enter that world.

Furthermore, the New London Group (1996) has discussed the necessity “to consider the implications of what we do in relation to a productive working life” (p. 66) but the group has not mentioned anything about the diversity of people living in our communities. From literate to less or non literate, there is a wide range of people; how can all students reach the successful lives they deserve? How can we be more aware of ‘differences’, be willing to eliminate the barriers between them, be open-minded? Thus, this is an issue for which more research should be conducted; perhaps people’s conscientiousness in that regards is not there yet.

Conclusion

Finally, students need to engage with school; even though they love learning they do not necessarily like school (Wesch, 2008). For this reason alone, educators have to find new ways of interacting with digital natives. Consequently, developing students’ digital skills will help them getting into the 21st century’s workforce, as some skills are expected from them; and schools are the best place to teach them. Moreover, the use of digital technologies and multimodal modes of representation will help assisting educators with the diversity of their students’ learning styles, and, also, those with special needs; it should help preparing them for a successful life.

References

Bolter, J. D. (2001). Writing Space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print. Chapter 3 (pp. 47-76). NY: Routledge.

Dobson, T. & Willinsky, J. (2009). Digital literacy. Retrieved from http://pkp.sfu.ca/files/Digital Literacy.pdf

Kress, G. (2005). Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge and learning. Computers and Composition. 22(1), 5-22. Retrieved from http//dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2004.12.004

Ong, W. J. (2002). Orality and literacy: the technologizing of the word. London: Routledge.

Prensky, M. (2010). Teaching digital natives: Partnering for real learning. Thousand Oaks: Corwin.

Rosen, L. D. (2010). Rewired: Understanding the iGeneration and the way they learn. Chapter 7 (pp. 149-177). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

The New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60-92. Retrieved from http://newlearningonline.com/~newlearn/wp-content/uploads/2009/03/multiliteracies_her_vol_66_1996.pdf

Wesch, M. (2008). A vision of students today. Retrieved from http://www.britannica.com/blogs/2008/10/1-vision-of-today-what-teachers-must-do/

A new landscape.

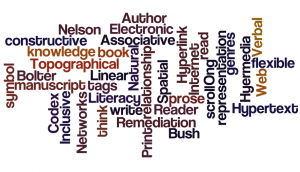

In his attempt to examine the changing landscape of representation and communication, Gunther Kress’s (2005) article titled, “Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge and Learning” raises many discussion points that are helpful for analyzing this field. His primary method of analysis is to setup dichotomies that imply competition between them with examples that include: semiotic signifiers and signs, representation and communication, display and story, and books and websites. While making these comparisons is useful, Kress tends to approach them from an either-or perspective in what I would suggest is a false dichotomy. Whereas it is apparent that the landscape here is changing from textual modes of representation to visual ones (often accompanied by auditory ones), I will describe how the latter is not supplanting the former, but enhancing or remediating it.

Bolter (2001) reminds us that, “[r]emediation can be, perhaps always is, mutual: older technologies remediate newer ones out of both enthusiasm and apprehension” and so we must consider the possibility, even probability, that textual modes affect visual ones and result in a hybridized mode with a synergistic effect. This is evident in the convergent appearance of websites, textbooks and magazines. The sense of urgency that brings with it the “Scylla of nostalgia and pessimism and the Charybdis of unwarranted optimism” (Kress, 2005) arises out of the centuries and millennia over which the modern text media have been remediating, picture writing, hieroglyphics, papyrus scrolls, manuscripts and other early text media. The remediation occurring in this late age of print (Bolter, 2001) is occurring over a few generations or less.

Turning to semiotics, on which he relies heavily, Bolter contrasts signifiers as symbols devoid of meaning in themselves and requiring interpretation with signs in which their meaning is clear and apparent. He continues to describe words as signifiers that require interpretation as to their meanings intended by the author or enunciator. While this description appears satisfactory (Martin & Ringham, 2006; Streeter, n.d.), he creates ambiguity in implying, however unintentionally, that images are akin to signs and then explains that in common sense, “meaning in language [i.e. text] is clear and reliable by contrast, with image for instance, which, in that same commonsense, is not solid or clear” before using obscure references to the 1992 Institute of Education prospectus and Simm’s 1946 book “The Boy Electrician” in an attempt to elucidate, which he fails terribly.

Where this unfortunate elucidation eventually leads is to a discussion of the relative power of the author and audience in different media, and more significantly the differences in the number of entry points often seen between multimodal websites and texts. The importance of these differences comes from the greater utility of a resource accessible by more readers in more ways that are pertinent to their life-worlds, as readers of texts become visitors to “pages” (for lack of a better word). This begins to get to the heart of the matter of the changing landscape: that multimodal pages, offer a variety of alternatives to and advantages over the fixed temporal organization of text, and Kress does well to list many of them.

Parallel to the alternatives and advantages offered by the multimodal, is the concept of the addition of tools to think with that the page designer has as well as of those available as a writer of text. Postman (1992) describes how literate societies have additional tools for thinking beyond those of oral societies, and it follows then that the addition of images to the vernacular of a society’s literacy will also bring with it changes to the ways in which its members think. As a result, page designers will need to critically examine their use of the different modes in their compositions so that they may intentionally leverage the affordances offered by their selected modes. Arguably, the intent of any composition is to communicate and do so effectively; however, the choice of how and to what extent pages are designed might greatly affect the extent to which their message is represented and received. By carefully leveraging the affordances of multimodal media, a greater level of depth and complexity, as well as specificity, in communication are possible. But to neglect these is to obfuscate the message, as many have witnessed in poorly designed pages with flashing images, and quantities of unrelated text.

As multimodal design continues to increase its dominance over mono-modal text, the nostalgic can be assured that text is not moving to obscurity but simply succeeding its dominant role, as is evidenced by the popularity of Harry Potter, Twilight and The Hunger Games with a generation most accustomed to, and inundated by, the multimodal. The unwarranted optimist warrants restraint in the knowing that visual literacy is a remediation of the textual as well as in the realization that just as poor writing is all too common, so is poor design. The more studious will take advantage of new tools and opportunities afforded by the multimodal to add layers of depth, complexity and universality to their design to enhance representation and communication

References:

Bolter, J. D., (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext and the remediation of print. New York: Routledge.

Kress, G. (2005). Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge, and learning. Computers and Composition, 22, 5-22.

Martin, B., and Ringham, F., (2006). Key terms in semiotics. London: Continuum.

Postman, N. (1992). Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. New york: Vintage books

Simms, J. W., (1946). The boy electrician. London: Harrap.

Streeter, T., (n.d.), Semiotic Terminology. Retrieved November 8, 2012 from http://www.uvm.edu/~tstreete/semiotics_and_ads/terminology.html