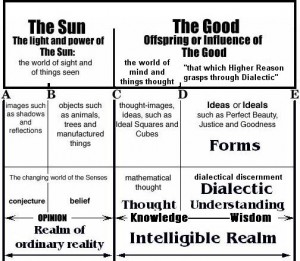

The question of societal transitioning from orality to literacy and the subsequent affects upon the societies in question has been central to the readings thus far in the course. In our Western society, we have seen a gradual change from orality to literacy from the time of the Greeks to present day. (Havelock, 1991) While the change towards literacy has happened quite recently in comparison to the life of languages as a whole, literacy has nonetheless become inextricably linked to Western society:

“The two, orality and literacy, are sharpened and focused against each other, yet can be seen as still interwoven in our own society. It is a mistake to polarize these as mutually exclusive. Their relationship is one of mutual, creative tension, one that has both a historical dimension as literate societies have emerged out of oralist ones-and a contemporary one as we seek a deeper understanding of what literacy may mean to us as it is superimposed on an orality into which we were born and which governs so much of the normal give and take of society.” (Havelock, 1991)

First Nations’ Literary Transitioning

It would be erroneous to assume that literacy is as inextricably linked to all other cultures as it is ours. Ong suggests that “of all the many thousands of languages-possibly tens of thousands-spoken in the course of human history, only around 106 have ever been committed to writing to a degree sufficient to have produced literature, and most have never been written at all. Of the some 3000 languages spoken that exist today only some 78 have a literature.” (Ong, 2000, p. 7) Many newly or semi-literate cultures exist close to or alongside literate ones, such as the First Nations groups which span North America, and more specifically, the First Nations groups of the Gitxan, Nisga’a and Shim Sham, upon whose territories I live in Northern British Columbia.

These groups have been thrown violently into the grasp of literacy, much unlike the European culture which “slowly moved over into the ambiance of analytic, interpretive, conceptual prose discourse.” The First Nations groups of Northern British Columbia were introduced to literacy approximately one hundred years ago, long after writing had been well established as a Western way of life. These peoples were forced to accept literacy and everything that went with it, such as formal schooling, as a predominant means of survival. The youth were forced into residential schools as a means of training them to become both literate participants in society, and “westernized”, in terms of behaviours and thinking. Whether this was based on a pre-planned conspiracy or simply misguided good intentions is not the focus here. Rather, the question that has arisen for me repeatedly since the onset of the course is “What has been the ultimate affect on the First Nations cultures in Northern British Columbia in particular, from having been forced into the literacy agenda long after the agenda was deeply entrenched in the Western society imposing it?”

A Fundamentally Oral Culture

The First Nations were historically an oral culture, with oral histories and oral documentation. As a result of the domination of the Western culture, they have been forced to incorporate the literary means of life with no historical markers to guide them on how to do so.

Western society has embraced literacy so much that the “rhythmic word as a storage well for information slowly became obsolete. It lost its functional relationship to society.” (Havelock, 1991, p. 25) The First Nations were simply thrown into this unfamiliar system which was dissimilar to their culture, which both embraces and credits the spoken word. Eigenbrod states that for the First Nations cultures “the truth and accuracy of the spoken words is guaranteed by the personal experience of the speaker: ‘What I do not remember, I will not say.’” (Eigenbrod, p. 90)

Despite these beliefs of their own culture, the First Nations groups find themselves having to defend their culture and territory, doing so by playing by the rules of the dominant literacy based society to the point where often from the Native perspective “literacy is associated with political power, dishonesty, and injustice.” (Eigenbrod, 90)

In the Delgamuuk trial, involving the Gitxan people of the Upper Skeen region, the Gitxan fought to have their oral histories recognized as viable proof of traditional land rights based on historical evidence of occupation of the territories in question. After a long and complicated court process, the Canadian Government agreed to recognize oral histories, ruling that “oral histories can be used to prove occupancy of the land and they will be given as much weight as written records” (Where are the Children website) with a stipulation attached designating control over the decision as to whether or not the oral histories are adequate proof resting on the Government’s shoulders. Again, despite recognizing the power and influence of oral history in the First Nations culture, the power of the literate society was ultimately imposed on the land title recognition process further solidifying the idea that “those who know how to write are in control and use their power to appropriate land that is not theirs.” (Eigenbord, p. 90)

The Struggles for First Nations Youth

While this example shows some of the struggles on a large scale, there are an abundance of smaller scale examples as well. First Nations youth struggle in the school system where they show “over-inclusion in various special needs categories and [have] literacy rates well below provincial averages.” (Fettes, p. 2) They are coming to literacy based schools from a home life and culture still linked in value systems and thought patterns of an oral society. One hundred years is simply not enough time to change over a pattern of thinking that has existed for more than 10 000 years. (Dickason, 1992)

First Nations cultures were those of hunter gatherer until the change of lifestyle brought on by the Europeans forced them away from their oral language patterns which were largely based on storytelling as a means of conveying history, record keeping and teaching through apprenticeship based learning.

What happens to these students who follow a social discourse of learning as “use of silence, listening and observing versus speaking, answering questions [and] demonstrating knowledge” (Peltier, 2009, p. 3) when they are introduced to a schooling model that values and rewards the very characteristics which oppose their oral apprenticeship style of learning?

The result is a gap between two cultures in terms of approaches to language, value of oral tradition, and ways of thinking which have been developed as a result of approaches to language. (Ong, 2000) Thought patterns that have been developed through the home culture oral developmental influences are suddenly put into question in the school system and seemingly need to be overwritten for academic success to occur.

Embracing Oral Teaching Techniques to Reach First Nations Learners

Research suggests that the techniques used to engage learning in pre-literate children are similar to those used in oral based cultures and thus may be transferable to newly-literate cultures such as the First Nations of British Columbia. Mark Fettes outlines in his paper, Imaginative Engagement in Culturally Diverse Classrooms: Changing Teacher Thinking and Practice within a Community-University Research Alliance, examples of the successful utilization of an imaginative educational approach in classrooms across British Columbia noting that “students from predominantly oral cultures…may have abilities of understanding and language use that are barely tapped in pedagogies oriented to text-based literacy….Imaginative education seeks to keep children’s oral abilities, and the kinds of understanding that accompany them, alive and developing throughout the school-age years.” (Fettes, 2005, p. 6)

Learning as a Culturally Mediated Activity

If learning is, as Vygotsky purports, a culturally mediated activity, (Lantolf, 1994) and the context of learning, oral or literary, shapes cultures as a whole, (Ong, 2000) how can we expect First Nations students to process information in the same way as students born into literacy cultures.

The question of First Nations students’ academic success seems to be a complex issue of colliding cultures, ways of thinking, and differences in approaches and goals of learning. Perhaps Ong is correct in asserting that literate cultures can never truly “conceive of an oral universe of communication or thought except as a variant of a literate universe”, (2000, p. 2)

However, in looking closely at the populations’ First Nations students that are not able to be successful in the literary based school system it seems necessary and timely to work within our limited frameworks of oral cultural understanding to attempt to create changes that could benefit these First Nations youth in our school systems.

In attempting to create a link that will enable success between the two, perhaps it is true that “no bridge built out of the certainties inherent in the literate mind can lead back into the oral magma” (Illich, 199, p. 34) but the need for at minimal a basic level of understanding is becoming apparent in order to provide students coming from cross-literal-oral backgrounds the support they require.

References

Dickason, Olive P. (1992). Canada’s First Nations: A History of Founding Peoples from Earliest Times. Retrieved from http://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=M5KhH8l1ldMC&oi=fnd&pg=PA9&dq=first+nations+gitksan+canada+practice&ots=MsYUCrksFf&sig=4_t59rQYwOlWjEebIrfTmOuiRbU#PPP1,M1

Eigenbrod, R. The Oral in the Written: A Literature Between Two Cultures. Accessed at http://www2.brandonu.ca/Library/cjns/15.1/Eigenbrod.pdf

Fettes, M. (2005) Imaginative Engagement in Culturally Diverse Classrooms: Changing Teacher Thinking and Practice within a Communitiy-University Research Alliance. Accesses at: http://www.csse.ca/CCGSE/docs/CCSEProceedings11Fettes.pdf

Havelock, Eric. (1991) The Oral-Literate Equation: A Formula for the Modern mind. Literacy and Orality. Cambridge University Press, New York. Accessed at http://books.google.ca/books?id=VKSIC5H8sd8C&dq=Literacy+and+Orality+Olson+torrance&printsec=frontcover&source=bl&ots=roCYFGBv4d&sig=cwhmP5ig5bkPBU1lFEtKx7slyBQ&hl=en&ei=WyzJSoGhMIa0sgPM49ihBQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1#v=onepage&q=&f=false

History or Indian Residential Schools. Assembly of First Nations. Accessed at http://www.afn.ca/residentialschools/history.html

Illich, I. (1991) Oral Metalanguage. Literacy and Orality. Cambridge University Press, New York. Accessed at http://books.google.ca/books?id=VKSIC5H8sd8C&dq=Literacy+and+Orality+Olson+torrance&printsec=frontcover&source=bl&ots=roCYFGBv4d&sig=cwhmP5ig5bkPBU1lFEtKx7slyBQ&hl=en&ei=WyzJSoGhMIa0sgPM49ihBQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1#v=onepage&q=&f=false

Judgements of the Supreme Court of Canada. (2007). Retrieved from http://csc.lexum.umontreal.ca/en/1997/1997rcs3-1010/1997rcs3-1010.html

Lantolf, J. (1994) Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Learning. The Modern Language Journal. 78, iv. Accessed at http://www.jstor.org/pss/328580

Ong, W. (2000) Orality and Literacy. Routledge, New York.

Peltier, S. (2009) First Nations English Dialects in Young Children: Assessment Issues and Supportive Interventions. Encyclopedia of Language and Development. Accessed at: http://literacyencyclopedia.ca/index.php?fa=items.show&topicId=276

Where are the Children: Healing the Legacy of the Residential Schools. Accessed at http://www.wherearethechildren.ca/en/history/