Determinism and Great Divide theory

In Orality and Literacy, Ong sets out some useful comparisons, but falls into the trap of implying that the categories he uses to describe and enumerate the differences between oral and literate cultures are sufficient to describe them. Further, in an attempt to support the Great Divide theory he elaborates, he ventures into technological determinism with the claim that technology shapes man—particularly, the way people think.

Ong (1982) writes: “Technologies are not mere exterior aids, but also interior transformations of consciousness, and never more than when they affect the word” (p. 81). This introduces a kind of chicken and egg argument since man has first to find a reason and the means to invent a technology in order for it to have its purported transformational effect on consciousness. In Ong’s view, writing is the technology that not only distinguishes oral from literate cultures, but also creates a schism between because it changes the very way they think: “More than any other single invention, writing has transformed human consciousness” (Ong, 1992, p. 77).

A more recent advocate of a similar view concerning the effects of technology on the minds of students is technophile Marc Prensky. He has famously argued that current students, whom he terms Digital Natives, have been mentally transformed by the various technologies to which they have been exposed to the point that the methods used by their Digital Immigrant teachers are no longer effective: “…it is very likely that our students’ brains have physically changed—and are different from ours—as a result of how they grew up” (Prensky, 2001). Prensky has been justly critiqued by numerous writers, including McKenzie (2007), who dismisses Prensky’s brand of determinism in Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants as “…a rather shallow piece lacking in evidence or data, Prensky offers the terms ‘digital natives’ and ‘digital immigrants’ to set up a generational divide. His proposition is simple-minded. He paints digital experience as wonderful and old ways as worthless.”

It should be noted, however, that notwithstanding his journey down the slippery path of technological determinism, Ong has done useful work in elaborating the distinctions between oral and literate cultures. If, in fact, his categorizations were a rhetorical device of the sort he discusses (Ong, 1982, p. 108), an agonistic means of illuminating the differences between literate and oral cultures, it would be more effective. Instead, as Chandler (1994) points out, such binaries lead to a “… sharp division of historical continuity into periods ‘before’ and ‘after’ a technological innovation such as writing assumes the determinist notion of the primacy of ‘revolutions’ in communication technology. And differences tend to be exaggerated.” There is also the danger of generalizing too widely and overlooking potential overlap.

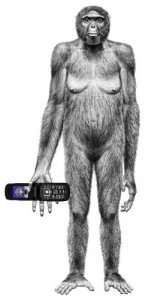

It is an interesting coincidence that in the same week the class is studying Ong’s Great Divide approach to orality and literacy, another classic Great Divide is being seriously challenged. News of ‘Ardi’ (short for Ardipithecus ramidus) a specimen of a female human precursor who predates the famous 3.2 million-year-old Lucy by a million years, appears to throw into question the missing link theory of human evolution (Shreeve, 2009). Paleontologists have long studied chimpanzees, assuming a human evolutionary path from apes to Lucy. Ardi now makes it appear that any common ancestor might have been much further in the past and unlike modern apes. Here again, the understandable, logical tendency to categorize, compare and contrast—strategies we teach students in English class to prepare their compositions—sets up overly simplistic false dichotomies which do not, ultimately, provide a complete picture.

As Chandler (1994) observes, dichotomy is sometimes an attempt to simplify complexity—in the case of orality and literacy, cultural complexity. Such complication is far more likely to result not in a clean break between orality and literacy, but in an overlapping of the various systems based on more mundane and practical considerations such as trade and commerce. This, in turn, challenges the elitism in the deterministic view such that, as Gaur (1992, p. 14) argues, there are no primitive scripts “…only societies at a particular level of economic and social development using certain forms of information storage” appropriate to their circumstances. Thus, continuity theories (Chandler, 1994), offer a more complete view incorporating the notion of interaction between overlapping modes and media which, in turn, allows for a more evolutionary and less deterministic understanding which eliminates the need for a missing link to explain historical discontinuities.

References

Chandler, D. (1994). Biases of the Ear and Eye: “Great Divide” Theories, Phonocentrism, Graphocentrism & Logocentrism [Online]. Available: http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/litoral/litoral.html

Gaur, A. (1992). A history of writing [revised edition]. London: British Library.

McKenzie, J. (2007). Digital Nativism, Digital Delusions, and Digital Deprivation [Online]. From Now On, 17(2). Available: http://fno.org/nov07/nativism.html.

Ong, W.J. (1982). Orality and Literacy. New York: Routlege.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. On the Horizon. NCB University Press, 9(5) [Online]. Available: http://pre2005.flexiblelearning.net.au/projects/resources/Digital_Natives_Digital_Immigrants.pdf.

Shreeve, J. (1 October 2009). Oldest “Human” Skeleton Found—Disproves “Missing Link.” National Geographic Magazine [Online]. Available: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2009/10/091001-oldest-human-skeleton-ardi-missing-link-chimps-ardipithecus-ramidus.html

2 replies on “What’s Wrong with Ong?”

You have given me a lot to think about.

I think that Ong admits some transitional forms between orality and literacy. I mention some in this post:

https://blogs.ubc.ca/etec540sept09/2009/10/04/orality-and-mythology/