An issue that has become more apparent to me during my revision of the course readings is that text is a constantly changing technology that is difficult to define. If the nature of text is that it is constantly being redefined than why have we not completely adjusted our teaching practices accordingly? If the current generation understands text as something that is viewed on a screen then their rules and definitions are different that the traditional views of text. Why do (primarily, elementary) educators concentrate on the current ‘archaic’ ways of teaching writing with a pen and paper if this is the case? I propose that this phenomenon is based on power struggles between educators and the public and a lack of technological assimilation in the school system.

Ong states that “There is no way to write ‘naturally’ (Ong, p.81).” This statement can viewed in a negative perspective. Should educators be teaching students in this day and age to write with a pen on paper and to practice their handwriting? The reality is that they will be using computers for the rest of their lives. Educators see this as an unnatural way to write. We are clinging to past views and perspectives by teaching writing and text in its current pedagogical form. Educators need to realize that it is alright to learn about and to use new technologies. It is actually natural to accept these new ways of learning and realize that this is the way of the future. “Technologies are artificial, but – paradox again – artificiality is natural to human beings. Technology, properly interiorized, does not degrade human life but on the contrary enhances it. (Ong, p.82)”

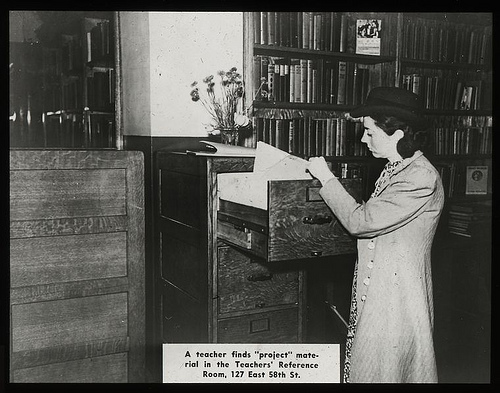

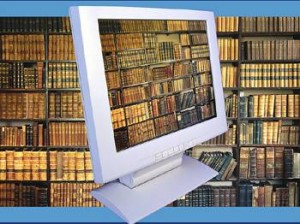

Despite what many educators may think, there is a benefit in teaching these modern technologies. Bowers states this idea clearly in the following quotation: “Computers continue the tradition of representing print as a form of cultural storage… (Bowers et al, p.188).” If we think about text in this context there is much that can be learned about our teaching practices. Some modern internet writing technologies are frowned upon. We tell our students that facebook is a waste of time, and we do not encourage use of online forums, but why? Could it be that educators are worried about losing their grip on the power of text technology? “Some societies of limited literacy have regarded writing as dangerous to the unwary reader, demanding a guru-like figure to mediate between reader and text (Goody and Watt taken from Ong, p..92).” It seems that educators are engaged in a power struggle to maintain their control over the education system.

Are we simply selling technology monopolies to the public in teaching reading and writing in its current form? In the 21st century there is a unique digression that is occurring in teaching text to students. Despite the changing requirements and needs for computer knowledge in the workplace, educators are not teaching these skills adequately. In elementary schools, computers are not seen as a core component of text education despite the fact that most currently written text is computer based. This situation is power based, and educators do not want to lose the influence that they currently hold. “Those who have control over the workings of a particular technology accumulate power and the workings of a particular technology accumulate power inevitably form a kind of conspiracy against those who have no access to the specialized knowledge made available by the technology (Postman, p.9).”

Students are often more engaged in learning when they are using technologies that they relate to. “Students are more willing to do more editing, to spend more time reviewing their text and improving it (Viadero, 1997b, p.13).” Despite this, educators still concentrate on older fashioned methods for text education, why? Ong has stated that often it takes time for modern technologies to be assimilated into our collective consciousness. Until this occurs there is always going to be a divide and a power struggle between teachers who believe in the ‘regular’ ways of teaching text and those that believe in the benefits of computer usage. “People had to be persuaded that writing improved the old oral methods sufficiently to warrant all the expense and troublesome techniques it involved (Ong, p.95).”

There is no doubt to me that text and computers are becoming more linked together. It is commonplace for students to submit their assignments electronically. The modern workplace requires the ability to write and read text electronically. One thing that I’ve realized through the first months readings is that text is a constantly evolving process, from its origins in the oral tradition to modern computers. As educators we need to be able to evolve with those technologies in order to provide the workforce of tomorrow a modern text education. This starts with educators being able to accept that perhaps, it is our socially responsible duty to provide this education. Until educators are willing to work with, not against modern text technologies we will always have this struggle. “Where technology is used and where the teachers are given the right kinds of support and training and the right kind of equipment, then (they) are able to actually implement some of the best theory and practice regarding the teaching of writing (Viadero, 1997b, p.13).

References

Ong, Walter, J. (1982). Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London and New York: Methuen.

Postman, N. (1992). Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. New York: Vintage Books.

Viadero, D. (1997b, November 10). A tool for learning. Education Week, 17(11), 12-13, 15, 17-18. Available: http://www.edweek.org/sreports/tc/

Bowers, et al. (2000) Native People and the Challenge of Computers: Reservation Schools, Individualism, and

Consumerism in American Indian Quarterly, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Spring, 2000), pp. 182-199.

This commentary will review the 1994 James O’Donnell essay, “The Virtual Library: An Idea Whose Time Has Passed”. After critiquing the essay, a synthesis will describe the two diverging arguments brought forth by the author, and the weaknesses of the conclusions reached.

This commentary will review the 1994 James O’Donnell essay, “The Virtual Library: An Idea Whose Time Has Passed”. After critiquing the essay, a synthesis will describe the two diverging arguments brought forth by the author, and the weaknesses of the conclusions reached.