Mythic Messengers – a huge bronze frieze depicting the orality of Haida culture and civilization

I am intrigued by Ong’s Euro-centric perspective on orality. Here, he asserts that the oral mind is aggregative, traditional, and “unable to detach itself from its context” (Bolter, 2001, p. 191). Ong further asserts that, “syllogistic reasoning…[is] foreign to a culture without writing (ibid). And, finally, Ong maintains that, “an oral culture simply does not deal in such terms as geometrical figures, abstract categorization, formally logical reasoning processes, definition, or even comprehensive descriptions, or articulated self-analysis” (ibid). In turn, I am compelled to offer a different perspective, for Ong’s claim seems to undermine the complexity and the intricacy of the intersection between orality and oral groups, peoples, and cultures. Specifically, I would like to introduce Indigenous knowledge through oral traditions like oral narratives.

For over thousands of years, Indigenous knowledge has accumulated because Indigenous Peoples have a close and interconnected relationship with their surroundings, observe their environment carefully, and learn through experience. Here, the teachings of Indigenous Peoples come from observing and learning from the water, the moon, the plants, the animals, the stars, the wind, and the spirit world. In turn, the world of Indigenous knowledge includes language, governance, philosophy, education, health, medicine, and the environment (McGregor, 2004). Thus, Indigenous knowledge is founded in “… the immediate world of personal and tribal experiences… and … spiritual world evidenced through dreams, visions, and signs” (Battiste, 1986, p. 2). Thus, by way of oral traditions and histories, this accumulated knowledge has been passed on to subsequent generations, using oral narratives like sacred creation stories, songs, historical events, cultural traditions, environmental knowledge, educational lessons, and personal life experiences (ibid).

However, as per the colonial impacts on Indigenous oral narratives, the forces of colonization affected the writing and the orality of the Indigenous Peoples of Canada. Here, the European colonizers rejected the “pictographs, petroglyphs, notched sticks and wampums [that] were the primary Native texts of Algonkian ideographic literacy” (Battiste, 1986, p. 2). The symbolic literacy of Algonkian was suppressed, and then replaced by the European written system (ibid). Furthermore, by way of the Indian Act, the forced assimilation affected the oral traditions of the Indigenous Peoples. The assimilation policies and regulations took over the social, the political, and the economic autonomy of Aboriginal Peoples. For example, the banning of speaking Native languages in residential schools has created a gap in transferring traditional knowledge to subsequent generations. In addition, various epidemics and diseases reduced the number of elders who were the custodians of the Indigenous oral tradition (Gill, 2009).

For Indigenous Peoples, oral narratives are relevant in today’s society because oral narratives connect the past to the present. Here, the orator constantly evaluates and balances “… old customs with new ideas” (Cruikshank, 1990, p. 21). As such, to address these challenges and to avoid resistance by the young generation, teaching oral narratives and stories necessitate qualification, guidance, and creativity of the elders who need to bridge the past to the present. Indeed, one of the significant elements of the Indigenous narratives is “… understanding of a worldview embedded in Aboriginal oral traditions” (Archibald, 2008, p. 13). A lack of cultural understanding of a particular Indigenous worldview limits the process of uncovering the layers that are embedded within the Indigenous stories, and Indigenous oral narratives may have many variations, metaphors, and symbols with implicit meanings and layers (Cruikshank, 1991).

Furthermore, animals and supernatural characters are present in most Indigenous traditional stories. In response to the reason for the presence of animal characters in the stories, Ellen White explains that, “If I was to mention a name and point at one of you I might be injuring you [and] the whole universe” (Archibald, 2008, p. 137). It is necessary to understand the Indigenous belief systems, worldviews, and cosmology before approaching indigenous oral narratives. In some oral narratives, the animals and the supernatural characters are neither fictitious nor fake. Instead, they are rooted in the Indigenous worldviews, cosmology, and belief systems (ibid).

Moreover, it is important to note the inherent challenges of translating oral tradition and oral narratives into the English language. This is due to the “… cultural boundaries” between Indigenous Peoples and non-indigenous people (Cruikshank, 1991, p. 6). Oral traditions include “a belief system” that is meant to be shared orally. When the Indigenous oral tradition is presented in written form, it hinders true understanding because written form fails to capture the cultural contexts in a meaningful way. Additionally, many non-indigenous writers and translators appropriate, distort, and exploit Indigenous oral narratives by, at least, romanticizing indigenousness by emphasizing ‘nobility’. In this context, language can become an instrument for perpetuating colonial stereotypes, tone, and attitudes (Archibald, 2008).

To survive as a people, Indigenous Peoples have accumulated valuable knowledge over thousands of years. This wealth of knowledge has been passed on to subsequent generations. To Indigenous Peoples, oral language is the most important vehicle of transferring Indigenous knowledge. More specifically, Kwiaahwah Jones of the Haida Gwai’i Nation, writes about the importance of oral language in that the “… Haida language is a link to our past, our present and our future [and] gives us a deep knowledge of the land and sea, and a way of thinking that is uniquely Haida” (Jones, 2009, p. 1). That is, Haida’s sophisticated ecological knowledge is reflected in its oral language. Haida words are very specific to its meaning. Through oral narratives, the elders have carried the responsibility of transferring the oral traditional knowledge to subsequent generations. Oral language is an essential instrument that allows the elders to communicate their knowledge to others, particularly children (Ramsay, 2005, p. 3).

Although Ong writes that oral narratives are found in all cultures and are more functional in primary oral cultures, he limits his perspective when he maintains that knowledge via oral narratives cannot be managed in elaborate scientific ways, that oral cultures cannot generate scientific categories (Ong, 1982, p. 137). However, the demarcation line between Indigenous knowledge and Western knowledge has resulted in differentiating between Indigenous and Western knowledge. That is, the Euro-centric perspective highlights the differences by labeling Indigenous knowledge as non-scientific, ‘primitive’, concrete, non-systematic, and localized (Agrawal, 2004, p. 3). Here, Agrawal states that there is “ intolerance of scientists towards insights and inquiry outside established, institutionalized science” (ibid). Agrawal believes that both Indigenous and Western knowledge should be considered as “multiple domains of knowledge, with differing logics and epistemologies” (ibid, p. 5). In addition, Barnhardt and Kawagley (2005) write that Indigenous Peoples “have studied and know a great deal about the flora and fauna, and they have their own classification systems and visions of meteorology, physics, chemistry, earth science, astronomy, botany, pharmacology, psychology” (p. 7). Certainly, it seems that categorizing and comparing Western and Indigenous knowledge have served only non-indigenous interest.

Overall, without oral traditions like oral narratives, Indigenous knowledge will be recorded only in text for viewing. Ong’s Euro-centric perspective does not consider this, for he states that the written word can exist, whereas oral narratives cannot exist without an orator (Ong, 1982, p. 11). However, in response to this, Indigenous communities have taken an active role in re-claiming their voices and re-telling their oral tradition. For instance, curriculum developers, Indigenous elders, and educators are working together in creating educational programs that value orality. Here, there is a need for creating a space for Indigenous communities in establishing curriculum that is based on their respective Indigenous traditions around oral narratives (Archibald, 2008, p. 83).

References

Agrawal, A. (2004). Indigenous and scientific knowledge: some critical comments. IK Monitor, 3(3). Retrieved October 1, 2010, from http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:clNYr-MDso0J:www-personal.umich.edu/~arunagra/papers/IK+Monitor+3(3)+Agrawal.pdf+Indigenous+and+scientific+knowledge:+some+critical+comments&hl=en&gl=ca

Archibald, J. (2008). Indigenous storywork: Educating the heart, mind, body, and spirit. UBCPress. Vancouver.

Barnhardt, R. & Kawagley, A.O. (2005, March). Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Alaska Native Ways of Knowing. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 36(1), 8-23. Retrieved October 1, 2010, from http://www.ankn.uaf.edu/curriculum/Articles/BarnhardtKawagley/Indigenous_Knowledge.html

Battiste, M. (1986). Micmac literacy and cognitive assimilation. In J. Barman, Y. Hebert, & D. McCaskill (Eds.), Indian education in Canada: The legacy (Vol. 1, pp. 23-44). Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Bolter, Jay David. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print [2nd edition]. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Cruikshank, J. (1991). Oral and written interpretations of the past. In Dan dha ts

edenintth e = Reading voices: Oral and written interpretations of the Yukon’s

past (pp. 11-21) Vancouver, BC: Douglas and McIntyre.

Cruikshank, J. (1990). My stories are my wealth: Angela Sidney. In life lived like story: Life stories of three Yukon elders. (pp. 21, 23-52). Omaha: University of Nebraska Press.

Curator & Collector: A Blog about the Art, Museums, and Numismatics of the Northwest Coast. Retrieved October 1, 2010, from http://curatorandcollector.com/?p=341

Gill, I. (2009). Guujaaw and the reawakening of the Haida Nation: All that we say is ours. Douglas & McIntyre. Vancouver.

Jones, K. How do we say cell phone in Haida? (2009, April) Haida Lass. A Special Language Edition. Retrieved October 1, 2010, from http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:oOeoAspCd2IJ:www.haidanation.ca/Pages/Haida_Laas/PDF/Newsletters/Language_09.pdf+Haida+Laas.+A+Special+Language+Edition&hl=en&gl=ca

McGregor, D. (2004). “Coming full circle: Indigenous Knowledge, environment, and our future” American Indian Quarterly. 28 (3&4).

Ong, Walter. (1982.) Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Methuen.

Ramsay, H. (2005, Winter). Preserving the Haida Language. Canadian Teacher Magazine. Retrieved October 1, 2010, from http://www.canadianteachermagazine.com/ctm_first_nations_education/winter05_preserving_haida_language.shtml

Boomers – Winners or Losers in the Age of Technology?

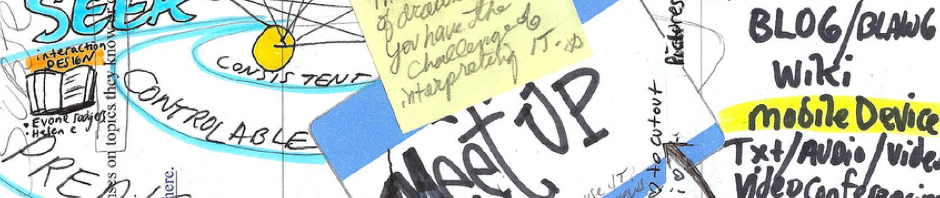

Postman’s theory of gains and losses is used as a framework through which issues facing the Baby Boom generation and its use of emerging text and communication technologies are examined. General attitudes toward technologies and specific motivations for and against the eventual uptake of skills and knowledge are addressed. For the purposes of this commentary, the Baby Boom generation is defined as having been born between 1946 and 1964. Similarly generations X, Y and Z are respectively defined as having been born between 1964 and 1981, 1982 and 1995, and 1996 and the present.

Baby Boomers are a unique generation in terms of how they view their relationship to the rapid evolution of technology. They span the digital divide, often unsure of the implications inherent in a decision to remain a technophobe or become a technophile (Postman, 1992). Boomers didn’t grow up with technology; O’Neill (2008) considers them to be ‘digital immigrants’, examining technology from an outsider’s perspective. The distinction between technophiles and technophobes illustrates Postman’s belief that there are winners and losers; gains and losses associated with the, “development and spread of computer technology.” (Postman, 1992, p.10) Postman’s stance of weighing the gains and losses associated with technology is relevant when examining the impact information technology is having on Boomers’ lives. However Postman’s theory is perhaps less applicable when examining the relationship subsequent generations (Generations X, Y and Z) have with emerging technologies. These generations have grown up fully immersed in information and communication technologies throughout their formative years—consideration of Postman’s gains and losses where they are concerned does not necessarily apply.

What has become apparent for Boomers is a pronounced shift in the balance of workplace power and mentorship away from themselves towards younger and less experienced members of subsequent generations, who have assumed the seat of power as it relates to technology. Innis focuses attention on knowledge monopolies, where “those who have control over the workings of a technology accumulate power and inevitably form a kind of conspiracy against those who have no access to the specialized knowledge made available by the technology.” (Postman, 1992, p.9) Members of generations X, Y and Z have a monopoly in the workplace when it comes to fluently using new technologies, leaving Boomers to fear that their accumulated decades of wisdom and experience will be lost if they are not able to match the speed of changing technologies and regain this lost power.

Change is the one, assured inevitability of technology (Postman, 1992). The last 25 years have seen a myriad of technologies introduced into the workplace. Postman further states that “such changes occur quickly, surely and, in a sense, silently… And it does not pause to tell us. And we do not pause to ask.” (Postman, 1992, p. 8, 9) With each new workplace technology comes a period of being an ‘unconscious incompetent’ for many Boomers. They lack the understanding around what new technologies can do, how they can be effectively used, and what the implications of employing these technologies might be. Soules (1996) writes that, “In order to understand any medium, we must attend not only to its physical characteristics, but also to the way in which it is employed and institutionalized.” (p. 2) Soules further notes that Harold Innis, “sees a dialectical relationship between society and technology.” (p. 2) Whether a Boomer chooses to remain a technophobe or to adapt to the mindset of a technophile will depend on the attitudes of that individual. Our past experiences determine our thoughts and beliefs, which then influence what we are willing to embrace or not.

For most Boomers technologies as they currently exist were not part of daily life as they progressed through formal learning environments prior to beginning their careers. Becoming familiar with the various technologies now available, and then keeping up with the rapid evolutions of each, is overwhelming at best. Members of generations X, Y and Z, who have grown up integrating new technologies into all areas of their lives, need not consider becoming familiar with emerging technologies as either a gain or a loss; rather it is simply part of how we now live.

Each evolution in technology represents an evolution in the way we think, communicate and interact with each other in the workplace and in society. This level of thinking in turn can be viewed as a form of personal currency in these realms. Boomers who accept technological defeat and choose to remain technophobes risk reducing their workplace currency considerably, regardless of wisdom and experience: a considerable loss. To embrace technology and the gains it brings they would need to overcome many of their negative ideas of how technologies impact our work and personal lives: a foreboding sense of impending dependence on an ever-evolving group of technologies, changing social norms associated with new technologies, the tension between continual availability and a struggle for ‘balance’, frustrating moments of technology-based inattention or interruption throughout the day, and Blackberries in boardrooms.

How technology is used is determined by the ways in which one perceives it as well as the way in which one participates in it. Bridging the digital divide requires both, “physical access to technology and the resources and skills needed to effectively participate as a digital citizen.” (Digital Divide, 2010) Innis believes that, “sudden extensions of communications are reflected in cultural disturbances.” (Innis, 1951) Boomers could be the groundswell of just such a disturbance, where the gains for them would be increased efficiency and productivity, the ability to remain dynamically connected to others and to workplace events as they unfold, powerful new skills and knowledge that fits well with their hard earned wisdom and experience. As technophiles, Boomers could regain their lost workplace currency.

References

Digital Divide. Retrieved October 2, 2010 from Wikipedia Web site: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_divide

O’Neill, J. (2008, December 28). More and More Baby Boomers Embrace Technology. Retrieved October 2, 2010 from Finding Dulcinea Web site:http://www.findingdulcinea.com/news/technology/2008/December/More-and-More-Baby-Boomers-Embrace-Technology.html

Postman, N. (1992). Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology. New York: Vintage Books, A Division of Random House, Inc.

Soules, Marshall (1996). Harold Adams Innis: The Bias of Communications & Monopolies of Power. Retrieved October 2, 2010 from Vancouver Island University Web site: http://records.viu.ca/~media113/innis.htm

Innis, Harold. (1951). The Bias of Communication. Toronto: U of Toronto. As quoted in Dobson, T., Lamb, B., & Miller, J. (2009). Prefatory Materials. Retrieved from https://www.vista.ubc.ca/webct/urw/lc5116011.tp0/cobaltMainFrame.dowebct