Here is my Major Project, which explores the changing relationship between text and image from the medieval to the digital age.

Introduction

The relationship between the visual and textual elements used in representation has changed in the time from the scribal culture of the Middle Ages through to the digital age, as new technology and changing sociocultural conditions have altered the balance between the image and the word.

Prior to the invention of the movable type printing press in the 15th century, scribes and copyists wrote manuscripts where the words and images were directly integrated, flowing from the same hand and pen and serving the same narrative goals. As Edward Tufte observed, “the words followed the images and the images followed the words” (2006, p. 90). However, the printing press separated the visual from the verbal (even in their physical production), leading eventually to a situation where the picture became subservient to the word.

Throughout the age of print culture, now seemingly in its waning days, text has fought off challenges from visual modes such as photography and film; however the emergence of computer technology has led to what J.D. Bolter has described as the “break out of the visual” (2001. p. 47), where the image has reasserted itself on the computer screen and now competes for control with text.

This competition presents challenges for designers and educators who must reconsider the roles of the author and audience – formed during the age of print culture – while they create digital content; as Gunther Kress noted, the “digital age brings with it a profound change in the relationship between authors, readers and knowledge” (2005, p.10). Additionally, text and visual modes offer different affordances, and content creators, no longer contending with technological constraints, now face an array of design decisions that did not exist in the age of print.

In this paper, I will analyze the historical relationship between the visual and the verbal, and how this relationship has served the construction of knowledge in the reader. I will discuss the implications of the current destabilized digital landscape where text no longer holds sway while also raising the question of how literacy may be defined in the digital age.

Background

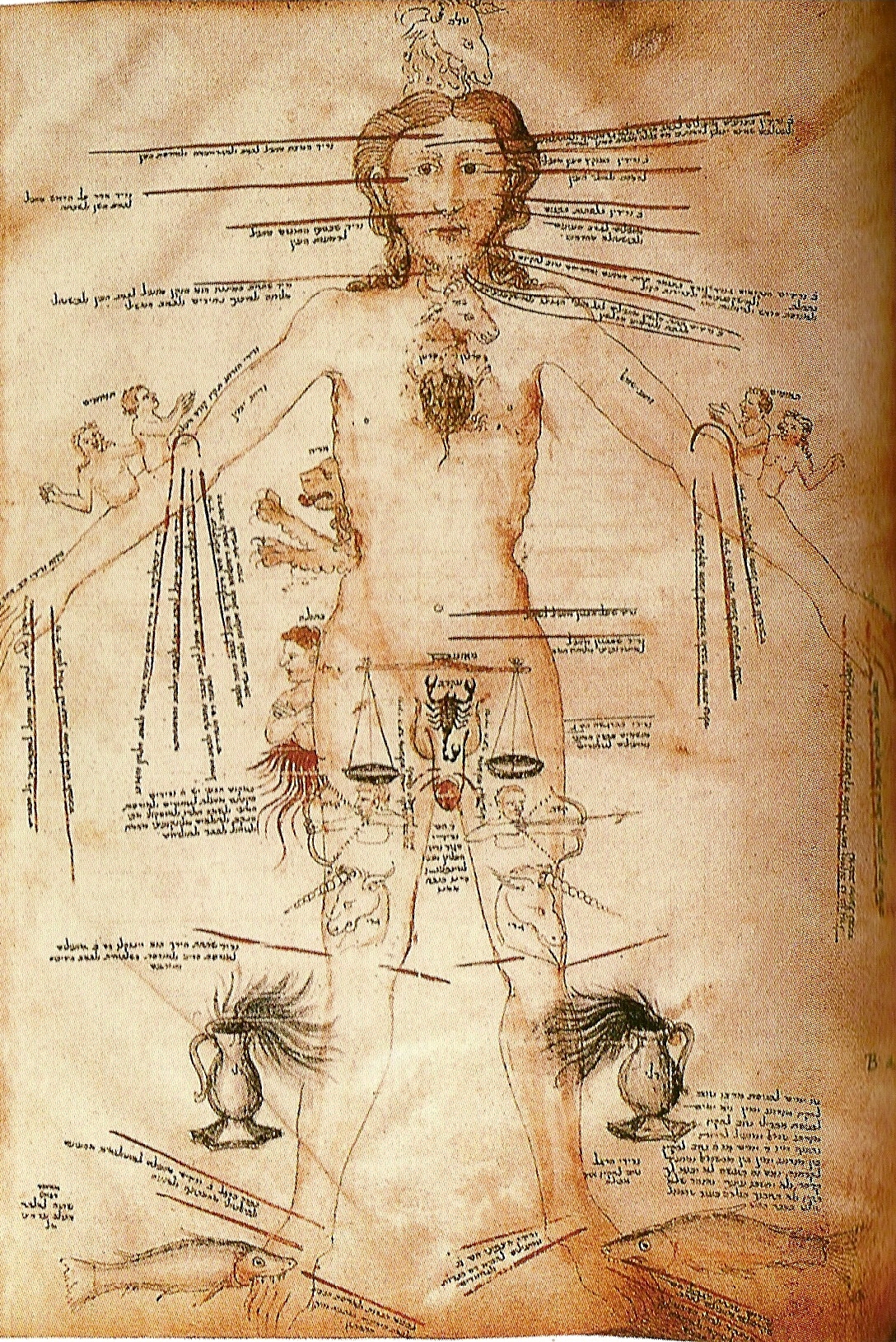

Astrological signs and the human body: 14th century manuscript

Text and image tended to be unified in representation during the Middle Ages in Europe, with hand produced manuscripts integrating words and pictures together in designs that were inherently multimodal, in part to make sense to a largely illiterate population.

With each manuscript drawn by hand, skilled scribes would create pages that seamlessly wove text and images together producing a unified visual-verbal display that was as much a picture as it was a written work.

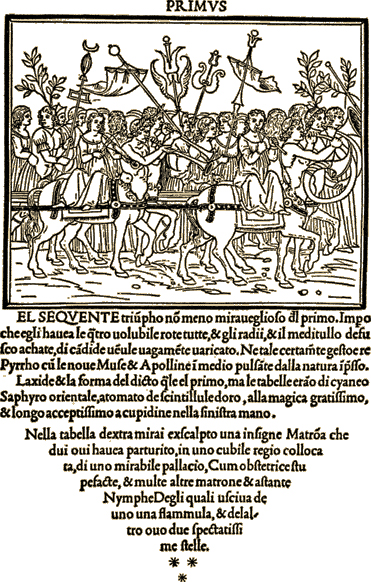

Manutius from Hypnerotomachia Poliphi from the 15th century

Early printing methods also maintained a unity between visual and verbal elements as printing remediated the medium of manuscripts. Text and images were physically created and cut together in a woodblock (in relief in reverse mirror image) and printed as one unit resulting in, as Edward Tufte observed, in his description of the Hypnerotomachia Poliphi (a famous woodcut print published in 1499), a “harmonious whole combining type and woodcut illustrations”. (2006, p. 88). And, while only 6% of this book is image, the text itself acts as a visual element. (Tufte, 2006).

Tufte argues that, as printing techniques began to segregate the production of images and text, the relationship between the two elements began to change. This can be seen in a number of publications in the 16th and 17th centuries as technologies evolved.

Galileo's "The Starry Messenger" from 1610.

Galileo’s “The Starry Messenger” published in 1610 used copper engravings to create images and embed them in the text, producing a beautifully integrated book; however the cost and complexity of the embedding process made it prohibitive for many publishers, who preferred to separate the pictures from the text.

This can be seen in Newton’s Opticks in 1704, a physics book presenting new information on the properties of light – certainly a topic lending itself to visual display – that presented its images in flaps separate from the text (Tufte, 2006), which may have been cheaper to produce but at the cost of verbal-visual unity. Stuart Sillars (2004) also noted that technology constraints in the 19th century continued to limit the number of images in books, as too many illustrations on a plate caused production difficulties. While late 19th century lithographic technology made it possible to simultaneously print text and image more efficiently, for much of the print era economics and technology promoted the separation of the elements, contributing to a imbalance between text and image in publications.

Pictures continued to have a role in representation as the post-printing press period progressed, but typically in the service of text (Bolter, 2001), with images supporting the narrative advanced by the text, either by placement – with the illustration slightly preceding the next to arouse expectations to be fulfilled by the text (Sillars, 2004) – or to act as graphical navigational tools (Drucker, 2008).

According to Bolter (2001), in the print era, writers used imagery and metaphor in order to produce the effect of visual display. Bolter refers to “ekphrais”, which is the process where words are used to demonstrate that they can describe visual scenes without the use of images. On this point, Drucker (2008) has noted that a unique affordance of text is that it allows the reader to take in textual representation and then visualize the story. Bolter suggests that prose and poetry met the challenge of newer visual media (photography and motion pictures) in the 19th and 20th century with even more extreme attempts to produce a sensory dimension. This is an example of remediation, where a newer medium borrows or imitates characteristics of an older or outmoded medium.

The Nature of the Verbal and the Visual

By its nature, communication is multimodal (Kress, 2005) but different modes have different “logics” and they create different relationships between the author, the reader/viewer and knowledge. Text representation possesses an authority that “transcends the material presence of words on a page” (Drucker, 2008, p. 95), and the reader is required (in most cases) to follow the thought order established by the author (Kress, 2005). Knowledge is presented in a linear sequential form, lending itself to the development of a narrative (envisioned and structured by the author), which reinforces the authority of the author’s voice. In contrast, visual content offers immediacy, and easily satisfies the desire to see the world (Bolter, 2001). Bolter also observes that visual display seems natural and appears not even to be representation at all. On the other hand, as cognitive neuroscientist Maryanne Wolf (2007) noted, reading is not a natural activity and our brains were not designed to do it. It is a learned activity.

The relationship between text and image is “blurred and complex” (Prior, 2005, p. 26) though, and the elements are not completely distinct. There is a visual grammar and spatial dimension to the presentation of text that influences the meaning making of the words. (Dobson, 2011) Over the years, print culture has developed methods of using graphic devices (indentations, page numbers, paragraphs, image location, etc) in order to aid navigation and support the narrative. These devices gradually became part of print culture writing conventions with readers largely being unconscious of their navigational role. (Drucker, 2008). However, their absence is striking when viewing manuscripts and early prints that do not use these tools.

The Digital Age

The onset of the digital age upset the balance between text and image, undermining the domination of the word, and pushing speech and writing “to the margins of representation to be replaced at the centre by the mode of image” (Kress, 2005, p. 17). As computer technology and graphic design improved, even better and more integrated image display became possible. The affordances of new media created an opportunity for images to break free from the limitations of words ultimately producing a unity between text and image on the computer screen not seen since the medieval codex (Bolter, 2001). Delivery had become truly multimodal, with text still providing its own distinct logic (sequential and narrative based) but having to share space with the immediacy of the visual, whether it was a still image or video. As Bolter (2001) observed, prose has become the last resort of a website designer, used when he or she had run out of ideas, time or resources. Websites followed a non-linear image-based logic offering multiple entry points (Kress, 2005) reducing blocks of text to pictures.

The altered balance between text and image on the computer screen has changed the relationship between author and reader, and has influenced how the reader – or more appropriately, the viewer – makes meaning from a variety of sign systems not just the alphabet, leading to a situation where the concept of reading (and literacy) may need to be rethought. Knowledge is no longer supplied; information is, which the viewer must order according to their own “lifeworld”, and then construct his or her own meaning. The role of the author as an authority is diminished; he or she must now, as a designer, consider the “aptness” of the mode of representation and how well it aligns with the needs of the imagined audience (Kress, 2005).

This makes the role of the designer considerably more complex than the author in the age of print, who, possessing the authority of a subject matter expect, was expected to express him or herself with words on a page, occasionally using pictures to support the order of the narrative. The creator of multimodal digital content has a series of design decisions that require knowledge of the affordances and “logic” of each mode and an understanding of the interaction of each one of them. As well, as our cultural understanding of how we navigate through textual and visual environments has largely been shaped in the age of print, and this understanding creates assumptions in the viewer on structure and design of sign systems (Drucker, 2008). In order to produce comprehensible work, designers must still function within the constraints of these culturally formed conventions. Also, literacy has historically been understood in terms of reading; the definition may need to be enhanced to include meaning making from a wider range of media.

Conclusion

However we a understand the post-printing press relationship between image and the word, it is clear that text is not now, and likely will never be again, the dominant mode of representation. Textual display has defined our understanding of meaning making for 500 years, but now, in the late age of print, tension between word and image has increased as they have become competitors for space on the computer screen: each one offering their own logic – one temporal and the other spatial. Still, even as scholars discuss the differences between modes, we must also remember that these elements are not entirely distinct and that there has always been interaction between the two: for example the spatial characteristics of textual data influence our understanding, and visual display may possess narrative properties as well. There is complexity to the relationship as new media remediate older forms.

The challenge before designers and educators is to function within an increasingly multimodal cultural and educational space, and to select appropriate modes for who they imagine their audience to be. They must also recognize that viewers still rely on culturally determined graphical and textual devices to support navigation and meaning making, and that these must be considered as new designs are conceived. Designers risk irrelevance is they move too far ahead of their audience.

Finally, entering the digital age will require us to think carefully about how we define literacy and how we want students to develop the capacity to make meaning from the range of sign systems they work within, and then, to develop meaningful measures of this capacity as we go forward.

References

Bolter, J.D. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Dobson, S. (2011). [Review of the paper Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge, and learning, by G. Kress]. Seminar. Net: International Journal of Media, Technology & Lifelong Learning, 7(2). Retrieved from http://seminar.net/index.php/reviews-hovedmeny-110/72-reviews/39-literacy-i n-the-new-media-age-by-gunther-kress.

Drucker, J. (2008). Graphic devices: Narration and navigation. Narrative, 16(2), 121 -139. doi: 10.1353/nar.0.0004

Kress, G. (2005). Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge, and learning. Computers and Composition. 22(1). 5-22. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2004.12.004

Prior, P. (2005). Moving multimodality beyond the binaries: A response to Gunther Kress’ “Gains and Losses”. Computers and Composition, 22(1). 23-30. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2004.12.007

Sillars, S. (2004). The illustrated short story: Towards a typology. In P. Winther, J. Lothe & H.H. Skei (Eds), The art of brevity (pp 70-80). Columbia, S.C: University of South Carolina Press.

Tufte, E.R. (2006). Beautiful evidence. Cheshire, CT: Graphic Press LLC.

Wolf, M. (2007). Proust and the squid: The story and science of the reading brain. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers.

All images Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Hi Andrew,

RE: “The challenge before designers and educators is to function within an increasingly multimodal cultural and educational space, and to select appropriate modes for who they imagine their audience to be. They must also recognize that viewers still rely on culturally determined graphical and textual devices to support navigation and meaning making, and that these must be considered as new designs are conceived. Designers risk irrelevance is they move too far ahead of their audience.”

I did my major project on multiliteracies which, as you know, considers multimodality, culture, design, and meaning making. I would venture to say that students as well as teachers need to choose their preferred modality for learning/designing when searching for meaning. I’m not sure I understand your last sentence in the quote above. Can you give me an example of moving too far ahead of an audience? Do you mean using an unfamiliar modality?

Hi Jennifer,

Irrelevance probably wasn’t the best choice of words, now that I think of it. But the point I was trying to make was based on Johanna Drucker’s work. Although I can’t think of a great example off hand to illustrate this, Drucker points out that our understanding of media is largely based on conventions, whether they are print-visual cues like paragraph indentations, reading from left to write, or more subtle devices, and readers/viewers use them to navigate through content. If they aren’t present, they have a harder time figuring out where they are going. For example, photographers are often trained to have leading lines follow from left to write to align with our reading style. If they switch it around, it can be jarring.

I probably should have fleshed that point out a bit more.

Andrew