In the first two modules of our course, we used Walter Ong’s 1981 text Orality and Literacy as a catalyst for discussion. It initiated a significant shift in my way of thinking about literacy, not as simply the ability to read and write, but as a doorway into a different world of thinking, one characterized by signs, symbols, abstraction, analysis and objectivity, but which also constitutes a loss of some elements of oral culture. One of our discussions hinged on the value of verbal memory and the memorization of poetry, just one example of a skill highly valued in oral culture, but much less valued in literate, and especially Internet-age culture.

Gordana Jugo talked about memorizing poetry as a child in school, saying she found there to be “an intimate relationship between person and poem that occurs.” This intimacy and connection with language can be abstracted and easily externalized in literate society, however, and more so in a culture pervaded by digital tools which are constantly reading, writing, and recording the world around us. In a literate culture, upon hearing a beautiful speech, a desire to share it might spur the listener to write it down (or in contemporary society record it), rather than to memorize it to repeat later. This ability to write or record something serves to stabilize, add permanence to, and offer the opportunity to revisit an otherwise fleeting auditory experience.

In Jay David Bolter’s (2001) book Writing Space, he cited one of the primary advantages of print as “fixity and accuracy,” that is, that once the human hand is removed from the production of each individual letter of text, it becomes much more stable, and subsequent copies of text can include improvements without introducing additional errors to the equation. Ken Buis described how the production and then private ownership of printed books brought about “a new shift in consciousness by moving print to an inert space and out of the auditory realm.” Print literacy in particular thus jumpstarted a process by which ideas came to be refined, developed, and built upon in a continuously advancing cycle, something which is not been possible to achieve in oral cultures in quite the same way, where ideas, however brilliant, are far more difficult to analyse, scrutinize, and build upon. In contrast, “when an argument becomes a visible and therefore durable structure in two dimensions, the reader can take the time to examine both the soundness of the parts and their relation to the whole” (Bolter, 2001, p.192). So while I would resist the idea that literate thinking is “better” I would certainly concede that literacy opens up possibilities for sharing and expansion of ideas which orality does not.

But these early modules were only the tip of the iceberg in terms of what now constitutes text, and what it means to be literate in a computer age flooded with digital information in the form of images, sounds, and words on screens.

Gunther Kress (2005) discusses how digital text and web pages have come to reject linearity and author-determined order of the printed book, empowering the reader to “fashion their own knowledge, from information supplied by the makers of the site” (p.10). Readers become visitors, participants in the construction of knowledge.

So too have Marc Prensky’s (2001) “Digital Natives,” the students of today, come to engage with the world around them as active members collectively building, sharing, and organizing knowledge. While his arguments have been criticized and dissected extensively in academia over the past decade, his essay served as a jumping off point for intensive discussions about why many teachers are currently struggling to engage their students in a meaningful way. Setting aside the Native and Immigrant metaphor for a moment, Prensky makes an effective point in arguing that students today, having grown up with digital technologies surrounding them, do think differently. They do, as he says, “prefer their graphics before their text rather than the opposite” and “prefer random access (like hypertext)” (Prensky, 2001, p. 2). This has more to do with access, however, than entertainment. To have a useful, explanatory image alongside text allows for a clearer understanding and application of the text in many cases, just as having one-click access to additional, elaborating materials benefits students in allowing them to go deeper into the subject matter if they so desire – without roaming through library stacks, no less! What Prensky (2001) sees as the emergence of a new, “native” culture, I see as the emergence of a generation which can (thanks to digital technologies and the Web) access, create, manipulate, share, organize, and transmit information multi-modally. Their insistence on graphics, video, podcasts, and hyperlinks is an insistence on getting the most versatile, complete view of the information being presented, something which should be encouraged and developed by teachers and administrators alike.

The New London Group (1996) had taken a close look at this changing literacy environment of the five years earlier, but instead of identifying changes in the students themselves, they focused on the environmental changes involving media, communication, and literacy. They responded with a new definition of literacy, which they termed “multiliteracies.” They argued that a traditional definition of literacy is limiting, that in a globally networked world, “negotiating the multiple linguistic and cultural differences in our society is central to the pragmatics of the working, civic, and private lives of students” (New London Group, 1996, p.1). This emphasis on social awareness is characteristic of a networked society in which information is produced and shared socially. Doug Connery cites Masterman (1985 and 1998), who “described the need for media literacy to support participatory democracy for citizens to have power, make reasonable decisions and to become change agents,” an idea championed by the New London Group (1996) as well, who suggest that promoting a pedagogy of multiliteracies would help students “to develop the capacity to speak up, to negotiate, and to be able to engage critically with the conditions of their working lives” (p.7). In short, to empower them to participate fully in society.

Becoming an agent of change, a producer of knowledge, or a full participant in society, importantly does not require any one person to become an individually prolific knowledge producer or sharer. Online social networks such as Facebook, Google+, Twitter, Flickr, and Youtube, as well as blogs, wikis, and other Web 2.0 tools which have materialized in the past decade have allowed information and knowledge to be produced, shared, and organized in the aggregate. One hundred thousand authors and over 20 million articles on Wikipedia are evidence of the power of collaboratively constructed and edited text, while hundreds of millions of Facebook and Twitter users share information and musings across cyberspace by sending, linking, and embedding text, images, videos, and audio.

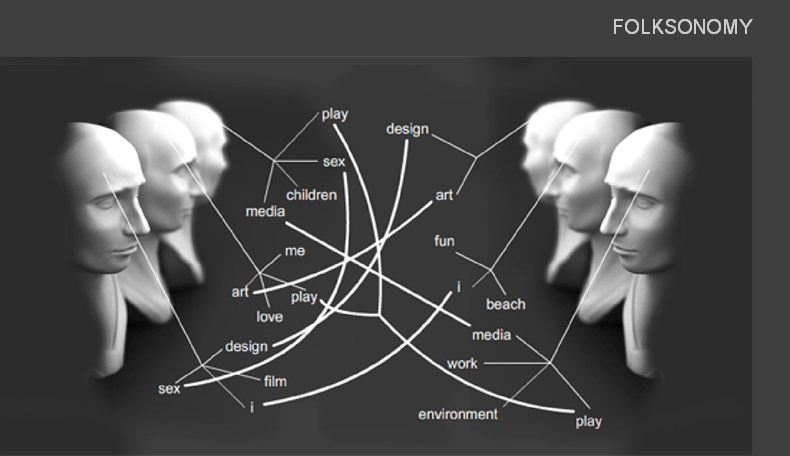

All of this content production and sharing has resulted in what Bryan Alexander (2008) calls social filtering, which in turn “has lead to the advent of folksonomies,” which “consist of single words that users choose and apply to microcontent” (p. 5). This system of labelling words has become a tremendously powerful engine of content organization and sharing. Users pay attention to the tagging practices of other users and adopt them rapidly, creating and spreading movements. Folksonomies are rapidly remediating traditional classification/organization approaches, improving on old taxonomic structures by employing the popular classification systems based on user preference.

Bolter (2001) threads the concept of remediation of writing mediums throughout his book, citing examples of how “one medium takes the place of an older one, borrowing and reorganizing the characteristics of writing in the older medium and reforming its cultural space” (p.23). That idea is extended from writing to all media in the final chapter of his book, where he describes the “breakdown of the distinction between elite and popular literature (and art in general),” saying that “our network culture, which rejects such hierarchical distinctions, finds in the Internet and the Web media that it can shape to express its preference for popular forms” (Bolter, 2001, p.208). The masses, having become literate and able to self-publish at will, have achieved true democratic power in this way, and they are gradually learning to wield it. Everyone has a say, and no one need be left out in the cold, although some undoubtedly still are. But longer do the elites make the rules about what the right way is to express an idea, or who has the right to express it.

One of the sticky issues that has come up in course discussions this semester with digital text is its permanence. How do I know that the webpage I read today will say the same thing tomorrow? Or if it will even exist next week? Or if the author ever completed his or her thought on the subject being presented? The freedom to express ideas on the Internet has led some to lament the tidal wave of information, much of which is garbage, half-baked, or unclear. Often the words produced by the masses link to other pages, ideas, and authors, following the author’s thought process by reading and clicking along. This hypertext format raises issues about when and whether a text is ever “ready” for publishing. One of the primary advantages of digital, Internet-based publishing is that it can adapt, it can update, it can correct its facts post-publication. In response to Jasmeet Virk’s questions about whether or not hypertext is ever finished, as well as whether or not it is safe “being prone to viruses, hacking, and malfunction electronic structures”, Everton Walker responded that “hypertext will always be work in progress as it has transcends the borders of print limitation. Our thoughts are always connecting to others and therefore there is always something to be added.”

So as the written word continues its ever-accelerating transition from symbols etched in stone to bits and bytes whizzing across cyberspace (and beyond), we are left with questions of permanence, of our own thought processes and preferences, of our transition from text-based information sharing to much more highly visual systems of communication.

How do we navigate the complexity of a hypertextual environment, and how to we instruct our students to do so as well, effectively? While I don’t think there are any easy answers, two major parts of the solution are continuing teacher education, and hand-in-hand with that, being involved in a community of practice. The socially-organized, multimodal pages of Web 2.0 are richer than ever, full of communities of forward-thinking, experienced educators eager to give practical suggestions for applying new tools in the classroom or send links to what they are reading to stimulate growth in their own teaching practices.

Text scratched into stone has evolved into text, pictures, video, and sound flashing through wires and waves, circling the globe in seconds. It is an evolution which will continue. Our students are chomping at the bit, ready to adapt along with it – are we ready to lead them?

Alexander, B. (2008). Web 2.0 and Emergent Multiliteracies, Theory Into Practice, 47 (2), p. 150-160

Bolter, J.D. (2001). Writing Space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Kress, G. (2005). Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge, and learning. Computers and Composition. 22. (pp. 5-22).London: University of London

The New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review. 66(1). p. 60-92.

Ong, W. (1982). Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the World. London: Routledge.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. Retrieved from: http://www.marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky%20-%20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf

Great and comprehensive work. I found all the chapters and topics interesting but your mention of Marc Prensky’s (2001) “Digital Natives,” is embedded in my mind and I don’t think it will be ever be removed. This is based on the fact that technology is here to stay which simply means that the future will be all about digital natives. This has serious implications for teachers, especially those who are unwilling to use technology in their instructions. As a result, I think that it should now be mandatory for all teachers to use technology in class and not just do things based on personal interest.

Everton

Insightful and thought provoking connections. I particularly connected to your comments relating to the challenges ahead for educators. “While I don’t think there are any easy answers, two major parts of the solution are continuing teacher education, and hand-in-hand with that, being involved in a community of practice” Continuing to connect to others, learn side by side (linked across time and space), and practice what we believe in, are important parts of this solution. Our students deserve no less! Helen