For my final project, I focused on the graphic novel. I have created a weebly site to show off my amazing attempts (now known as Exhibit A in the case as to why I should not be an art educator) at creating comics and graphic novels. The site also includes important vocabulary and additional resources. My final project paper is below, if you want to avoid burning your eyes out with my comic creations. (I’m trying to be humble, but I am really quite proud of my creations.)

Thanks,

Kym

Getting Graphic:

Using Graphic Novels in the Language Arts Classroom

Sequential art narratives are images structured into a sequence to tell a story. Carter (2009) outlines the transition of sequential art, from cave paintings to comic books to the graphic novel. The first comic book was published in 1938, and children very quickly began collecting and exchanging them. Unfortunately, by the 1960’s, a combination of criticism and the advent of the television left comic books by the wayside (Monnin, 2010). In the 1970s, comic artists responded to societal assumptions that comics were immature and created graphic novels to prove the opposite. Chun (2009) defines graphic novels as original, book-length fiction or non-fiction stories, with mature themes and complex narratives, published in a comic book style. Graphic novels provide a reading experience with simultaneous images and text, as if the reader is both reading and watching a movie simultaneously. Jim Steranko created Red Tide and Will Eisner wrote and illustrated A Contract with God in 1978. Since these were first published, graphic novels have garnered critical acclaim; Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel, Maus II, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1992 and Gene Luen’s <em “mso-bidi-font-style:=”” normal”=””>American Born Chinese won the Michael L. Printz Award in 2007 (Monnin, 2010).

In more recent years, graphic novels have inspired countless films and television shows. Today, society is dominated by the visual image, and transmedia is becoming more prominent. Today, society is dominated by the visual image. Television, films, magazines, and the Internet are using images to communicate, entertain, and profit (Gillenwater, 2009). Graphic novels have impacted the images we view daily. Movies such as Batman, Spider-Man, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, and Iron Man are all based on graphic novels (Behler, 2006). Television shows, such as The Walking Dead,Smallville, and The Human Target are based on graphic novels.

Educational Implications of Visual Literacy

Chun (2009) outlines the 2004 PISA 2000 report, which surveyed the teens of 43 countries. Research found that students’ level of reading engagement was more important than socioeconomic background as a predictor of literary performance. Educators with marginalized students, with limited access to resources, can nurture a love of reading to eliminate these socioeconomic barriers to success. Moreover, increasing student engagement in reading provides a gateway into social groups and networks in the classroom, community, and world through book clubs, blogs, chat groups, and other online activities (Chun, 2009).

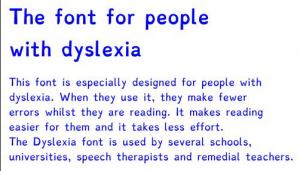

Visual literacy is the reading of text and images in conjunction, and requires traditional reading skills as well as ability to read frames, gutters, speech bubbles, and other graphic novel features (Monnin, 2010). Students need access and interaction with both print and visual literacy in order to be best prepared for the demands of the 21st century. Both literacies require interpretation, negotiation, and meaning making from readers, which in turn supports student ability to interpret the world. Graphic novels provide the ideal vehicle for both print and visual literacy skill to be developed in the classroom (Gillenwater, 2009).

Despite the prolific nature of visual images, many educators continue to use traditional text and “teach a one-dimensional concept of literacy, while students learn to negotiate their out-of-school experiences with images via …personal trial and error, peers, and from the media itself” (Gillenwater, 2009, p. 33). The popularity of graphic novels has led educators to question their validity in the classroom. Some educators consider them to be a dumbed down version of literature and inappropriate for children. In actuality, graphic novels are effective tools for fostering literacy skills (Monnin, 2010).

Griffith (2010) summarizes prior research regarding the effectiveness of graphic novels as an educational tool. Graphic novels support vocabulary development, language learning, motivation to read, and reading comprehension through effective combination of print and visual literacy in a mutually complimentary manner. Because graphic novel text does not describe what is happening in the illustrations, it demands a sophisticated level of literacy from the reader (Gillenwater, 2009). Dialogue and complex literary elements such as symbolism, imagery, and theme are woven between the text and images presented on the graphic novel page; the reader must synthesize these elements to understand the story being told.

Readers are drawn into the graphic novel narrative through their own complex visual and print language that requires readers to use imagination and inference. Students incorporate text, pictures, facial expressions, panel progression, color, and sound effects to find meaning. Graphic novels are one example of sequential art, and are considered effective means of engaging reluctant readers and inspiring motivated readers. Graphic novels have been found to attract new readers, motivate male readers, and challenge gifted students (Carter, 2009).

Carter (2007) identifies three ways that students can view graphic novels: cross curricular, as complimentary to traditional classroom text, and using contact zone theory to examine social issues. Contact zone theory challenges teachers and students to critically examine issues from multiple points of view in order to dialogue with others. Through these three lenses, graphic novels support student learning of social issues and development of personal opinions on justice.

The Depth of Graphic Novels

Graphic novels encompass fiction, historical fiction, and non-fiction, and cover a variety of themes and topics, including true crime, history, science, biography, and memoirs (Behler, 2006). Additionally, graphic novels deal with mature and relevant topics to students, including date rape, natural disasters, genocide, and violence. Equally important, they focus around adolescent issues such as coming of age, identity, and friendship (Carter, 2009). Their educational value and universal appeal make them an important part of the Language Arts curriculum (Behler, 2006).

Outside of Language Arts, graphic novels are powerful tool for teaching history (Monnin, 2010). Chun (2009) articulates the value of historically-based graphic novels, such as <em “mso-bidi-font-style:=”” normal”=””>Maus, for their ability to communicate historical content in an engaging and meaningful way. He argues that students “can mediate these historical realities with their unique visual narrative styles that allow many readers, especially adolescent ones, to imagine and interpret characters’ experiences that are far removed from their own daily lives” (p.. 146).

Chun (2009) speaks to the human value of graphic novels, stating that “graphic novel[s] can potentially influence students’ lives. Reading these powerful narratives gives students a sense of ownership over these texts through their intellectual and emotional engagement with them” (p. 152). By using their own background knowledge, students can connect to the graphic novel stories and understand global issues at a deeper level.

The Gutters and Panels

Monnin (2010) describes how the gutter and panels work together to tell a complex story. The gutter, or space between the panels, creates moment for readers to infer and use their imagination to move the story along. Even though each panel includes its own story and plot elements, it is the gutters that glue the story together. There are several types of panels: word, image or word and image combined. In addition to these categories, Monnin (2010) describes eleven types of panels, including plot, character, and conflict. Through the varied use of these panels, in partnership with word, thought, dialogue, and sound effect balloons, complex stories are told. The reader must interact with the text, making critical connections, to comprehend and extend the story.

Graphic Novel & Visual Literacy

According to Monnin (2010), students must activate reading strategies to comprehend graphic novel text with efficiency and fluency. Carter (2009) states that there is a need “for authentic reading and writing experiences, textual investigations that help bridge the gap between the school world and the lived world” (p. 72). Reading and writing graphic novels can motivate struggling and reluctant readers, support multimodal learning, and foster 21st century learning. It is fundamental that youth develop multimodal literacies, as they are exposed to them on a daily basis. Research shows that students experience greater success when they interact with a wide range of texts, and graphic novels offer a way to encourage multiliteracy skills. (Hughes et al., 2011)

Visual literacy is becoming more and more important, as visual communication is considered to be more powerful than words. Graphic novels and comic books support this shift from traditional text. “The nature of graphic novels – with frames around moments in the story and the interconnectedness of the text with the image – fits into the definition of new media. It is reminiscent of screenplays and film.” (Hughes et al., 2011, p. 602)

Carter (2009) suggests that educators think beyond just encouraging the reading of graphic novels. Instead, students need to be planning, writing, and illustrating graphic novels as authentic writing activities. “By acknowledging that there is a process behind the production of comics and asking students to consider the process and even engage in it, teachers help students build crafting, composing, viewing, and visualizing skills” (Carter, 2009, p. 71). Students hone writing skill and create stories that connect to life experiences and relevant social issues.

Chun (2009) encourages the use of graphic novels as a means to support language learning and multiliteracies, which “work to promote learning that recognizes students’ own knowledge resources” (p.145). Students with learning disabilities, and those in need of visual support, benefit from reading graphic novels. Visual and spatial learners learn best from materials with a visual element; in addition to graphic novels, educators need to include graphic organizers, picture books, graphic notes, and mind mapping (Kluth, 2008). Computer software and web 2.0 tools are available for students to write, design, and create their own graphic novel stories. When students are encouraged to share text with peers, family, teachers, and the broader public, they grow in self-confidence, self-esteem and community belonging (Cummins, Brown, & Sawyer, 2007).

The Dark Side of Graphic Novels

Graphic novels haven’t always been seen as educationally sound resources. Teachers are often reluctant to utilize graphic novels. This may be due to a lack of awareness for the current research supporting the benefits, lack of teacher testimonials, and lack of policy in regards to the use of graphic novels (Carter, 2008). There are certainly limitations in the use of graphic novels in the classroom. Graphic novels do not function well as read-aloud books, which limits group reading. Students lacking in confidence may balk from reading with others. Lastly, individual reading pace may impact graphic novel work negatively. (Hughes et al., 2011)

Critics have expressed concerns that there is a gender gap in readers, specifically that girls dislike graphic novels. Moeller (2011) reports that graphic novel elements tend to appeal to boys more than girls. Girls are attracted to fiction that centers on character relationships, whereas boys connect with text of a non-fiction nature that emphasizes action. Beyond gender differences, all readers appreciate a connection with the characters.

Additionally, it has been found that there is a negative social association with graphic novels. Moeller (2011) explains that young people feel graphic novel reading creates a subculture of nerds. Although both male and female students enjoy reading graphic novels, both genders expressed difficultly balancing what they find engaging and what is socially acceptable. Students described graphic novel reading as nerdy; those that enjoy graphic novel reading in public would be ostracized and ridiculed by popular groups. Moreover, Moeller’s research found students were concerned about judgment from teachers. Although students were initially excited to read graphic novels, they didn’t believe their teachers would value the graphic novels over the traditional novel choices read in class.

Despite these challenges, graphic novels are effective hooks for reluctant and struggling readers, and support visual literacy and comprehension as students make inferences across the gutters. Hughes et al. (2011) report that students engaged in creating graphic novels were excited to complete the project. Even those who struggled with traditional writing created meaningful stories. All students involved demonstrated personal growth and development of multimodal literacy skills and literary elements such as plot, characterization, setting, and conflict.

The Weight of Educating with Graphic Novels

In order to support the value of graphic novels in the classroom, educators must ensure effective and responsible use of visual text. Not all graphic novels are appropriate for a young audience; educators must preview and evaluate resources prior to using them in the classroom. Educators must read each page and each panel carefully, and evaluate the graphic novel in relation to curriculum standards (Carter, 2009).

It is of utmost importance that content and readability levels are evaluated by educators before students use them. Griffith (2010) encourages educators to evaluate the text, illustrations, and content for appropriateness and effectiveness. In addition, consideration needs to be given to the conflict and themes represented in the graphic novel, to ensure they are appropriate for the age of the reader. In addition to evaluating resources on a professional level, Carter (2009) encourages educators to provide parents and students an opportunity to preview graphic novels and discuss the central issues before they are utilized in the classroom.

Graphic novels can be used in the classroom to build students’ vocabulary, reading comprehension, and writing skills. Educators need to be aware of the high-quality graphic novels available to young adults today. Similarly, schools need to add graphic titles to their libraries and teachers need to create and share plans and articles on the subject to continue to advance the practice of teaching with graphic novels (Carter, 2007).

Conclusion

Graphic novels have received attention for their ability to motivate reluctant readers and support multiliteracies. However, graphic novels are not only for readers who struggle. Carter (2009) summarizes the research of Mitchell and George (1996), who found that sequential art benefits already motivated readers and supports the examination of ethical issues with gifted students. McTaggert (2008) reminds educators that they need to teach graphic novels because “they enablethe struggling reader, motivate the reluctant one, and challenge the high-level learner” (p. 32). In addition, graphic novels improve reading comprehension while complimenting the other core curriculum areas (McTaggert, 2008).

Carter (2009) reports that certain populations prefer to read visual texts and students who don’t typically connect with literature will be motivated to read graphic novels. Furthermore, students who struggle with English language literature will be able to increase comprehension through the use of images and text combined in graphic novels. Lastly, readers who find motivation on the pages of a graphic novel will begin to read other texts, using the graphic novel as a gateway to other literature.

Graphic novels are changing way we educate students in the Language Arts classroom, not only by changing the texts used to learn but also by challenging the traditional learning practices. Educators need to change as well; we need to pay attention to what students are reading for enjoyment, read graphic novels ourselves, and bring appropriate texts into the classroom to interact with.

References

Carter, J. B. (2009). Going Graphic. Educational Leadership, 68-72.

Carter, J. B. (2007). Transforming English with Graphic Novels: Moving toward Our “Optimus Prime”. The English Journal, 97(2), 49-53.

Chun, C. W. (2009). Critical Literacies and Graphic Novels for English-Language Learners: Teaching Maus. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 53(2), 144-153.

Cummins, J., Brown, K., & Sayers, D. (2007). Literacy, technology, and diversity: Teaching for success in changing times. Boston: Pearson.

Gillenwater, C. (2009). Lost Literacy: How Graphic Novels can Recover Visual Literacy in the Literacy Classroom. Afterimage, 37(2), 33-36.

Griffith, P. E. (2010). Graphic Novels in the Secondary Classroom and School Libraries. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 54(3), 181-189.

Hughes, J. M., King, A., Perkins, P., & Fuke, V. (2011). Adolescents and “Autobiographies”: Reading and Writing Coming-of-Age Graphic Novels. Journal of Adolescent & Adult LIteracy, 54(8), 601-612.

Kluth, P. (2008). “It Was Always the Pictures…”. In N. Frey, & D. Fisher (Eds.), Teaching visual literacy: Using comic books, graphic novels, anime, cartoons, and more to develop comprehension and thinking skills (pp. 169-188). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

McTaggert, J. (2008). Graphic Novels: The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly. In N. Frey, & D. Fisher (Eds.), Teaching visual literacy: Using comic books, graphic novels, anime, cartoons, and more to develop comprehension and thinking skills (pp. 27-46). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Moeller, R. A. (2011). “Aren’t These Boy Books?”: High School Students’ Reading of Gender in Graphic Novels. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 54(7), 476-484.

Monnin, K. (2010). Teaching graphic novels: Practical strategies for the secondary ELA classroom. Gainesville, FL: Maupin House Pub.

Wallace, C. (2001). Critical literacy in the second language classroom: Power and Control. In Negotiating critical literacies in classrooms (pp. 209-228). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

MEDIA AS METAPHOR?

COMMENTARY 3: MEDIA AS METAPHOR?

Reading the last two chapters of Bolter’s Writing Space I found myself wondering what does ‘writing the self’ mean?, what would be the implications of this process? Bolter (2011) immediately suggests that

“it seems almost inevitable that literate people would come to regard their writing technologies as both a metaphor for and the principal embodiment of thought…. It may be that cultures invent and refine writing technologies at least in part in order to refashion their definitions of mind and self (p. 189).

In this very intimate relationship of language, self and technology, is technology only a metaphor? From the 1960s when McLuhan first prophesied that the ‘medium is the message’, many theorists like Postman (1992) and Heidegger (1977) have insisted that people needed to become aware of the hidden agenda of technology, its power to create unforeseen effects – this is much more than a metaphorical relationship. The clash of powerful forces characterizes the continuing evolution of social structures and self-image through the technologies of writing, and the current embodiment of the self as a “human-technology symbiont”, in Andy Clark’s (2003) words.

The transformational power of writing on human consciousness (Ong, 1982) gave rise to the reflexive consciousness, the gradual separation of self/other; the knower/known, and the rise of objective scientific knowledge (Eisenstein, 1979). In this way, the paradoxical reflection on the effects of the technologies of writing on self/mind and culture could unfold only through the use of the technologies of writing- so now with digital multimedia (Ong, p.79).

Andy Clark (2003) traces the “cognitive fossil trail” of writing technologies through writing, printing, to digital multimedia, each successively representing “mindware upgrades” as our technologies become ever more complex, multimodal and miniaturized – “cognitive upheavals in which the effective architecture of the human mind is altered and transformed” (p. 4). The self-mind, instantiated in its technologies now dwells in cyberspace – in a world of instantaneous texts, transient digital signals, globally connected to millions of other ‘selves’ where image, sound, icon, electronic writing and collaborative creations all mix and mingle in the creation of multiple meanings. In the face of this, the independent, stable author of the closed text; the Cartesian rational, cognizing self has morphed into “a fragmented and constantly changing postmodern identity” (Bolter, 2011, p. 190).

Postmodern Cyborgs

The strangeness in seeing ourselves in our technologies, describing our bodies and minds in their terms is overcome once we realize that this is not a mere metaphor, a comparison between two different things that can help us elucidate essential features of each thing. Bolter goes on to suggest that writing is a metaphor in a strong sense – an ‘identification’ of the two, intimacy of technology and mind (p. 193). The postmodern age understands that the dichotomies of self/other, nature/culture etc. no longer apply. For Clark (2003), our technologies extend and complement our senses, modes of ‘processing’, problem-solving and thinking – “the tools and culture are indeed as much determiners of our nature as products of it” – indeed, our thinking, imagining, feeling self is embodied in these technologies now – mind is not only what’s inside the “fortress of skin and skull” (p. 4,5).

How has digital technology remediated the printed word and so the writing of the self? The very concepts of text and literacy have expanded as fast as the digital technologies have brought audio, video, film, images and icons, collaborative creative spaces, instantaneous searches and connections to everyone’s fingertips. Barthes (1977) describes the implications of these new texts and the millions of readers that have become authors: “We know now that a text is not a line of words releasing a single ‘theological’ meaning (the message of the author-God) but a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash” (par. 5) – ourselves seem to be everywhere.

http://www.publicdomainpictures.net/hledej.php?hleda=computer

http://www.public-domain-image.com/objects-public-domain-images-pictures/electronics-devices-public-domain-images-pictures/computer-components-pictures/computer-sound-card.jpg.html

The intimacy of text and technologies is in the organism’s DNA and inscribed in the circuitry itself as Haraway (1991) writes: “The silicon chip is a surface for writing; it is etched in molecular scales disturbed only by atomic noise, … Writing, power, and technology are old partners in Western stories of the origin of civilization, but miniaturization has changed our experience of mechanism. Miniaturization has turned out to be about power; small is not so much beautiful as pre-eminently dangerous” (p.153), as hard to see politically as materially.

Turkle’s (2004) research highlights impacts of digital technologies on people, and the apparent comfort with multiple identities in online virtual worlds; and children interacting with digital devices from digital pets to phones,. As Clark (2004) points out, we are already part of this invasion of the miniature in our phones, ipads, ipods, trackers, implants, nanobots: “minds and selves are spread across biological brain and non-biological circuitry” (p. 3).What kinds of cyborg selves and relationships are being written? For Haraway, it is critical to realize that machine and organism are coded texts “through which we engage in the play of writing and reading the world” (p. 152), that there is a need for creative imagination in order to write the kind of world we want, be the selves we desire, to deflect the “the final imposition of a grid of control on the planet” (p.154). And McLuhan’s (1962) question is still important: “is it not possible to emancipate ourselves from the subliminal operation of our own technologies?” (p. 246). Is the subliminal the circuitry of our bodies or the electronic structures?

References

Roland Barthes. (1977). The Death of the Author in Image, music, text, (Richard Howard, trans.). Retrieved from: http://evans-experientialism.freewebspace.com/barthes06.htm

Bolter, J. D. (2011). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Clark, A. (2004). Natural Born Cyborgs: Mind, technologies and the future of human intelligence. London: Oxford University Press. Excerpt article published by Edge/Third Culture Series. Retrieved from: http://www.edge.org/3rd_culture/clark/clark_index.html

Clark, A. (2003). Natural Born Cyborgs: Mind, technologies and the future of human intelligence. London: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from:

http://it.mesce.ac.in/downloads/CriticalPerspectives/booksforreview%20CPT%20S7/Clark%20E.%20Natural-Born%20Cyborgs-%20Minds,%20Technologies,%20and%20the%20Future%20of%20Human%20Intelligence.pdf

Eisenstein, E. (1979). The printing press as an agent of change. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Haraway, D. (1991). “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century,” in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York, NY: Routledge, 1991), pp.149-181. Retrieved from: http://www.stanford.edu/dept/HPS/Haraway/CyborgManifesto.html

McLuhan, M. (1962). The Gutenberg galaxy: The making of typographic man. ON: University of Toronto Press.

McLuhan, M. (1969) The Playboy Interview: Marshall McLuhan. March 1969 ©, 1994 by Playboy.

Retrieved from: http://www.mcluhanmedia.com/mmclpb01.html

Ong, W. J. (2002). Orality and literacy (2nd ed.) New York, NY: Routledge.

Postman, N. (1992). Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. New York: Vintage Books.

Turkle, S. (2004). Whither psychoanalysis in computer culture? Psychoanalytic Psychology,

21(1), 16–30. DOI: 10.1037/0736-9735.21.1.16