Heavy Heroes: More than just memorable

The Cultural and Psychological Roles of Heroic ‘Heavy’ figures and of the Bizarre in Ancient Mythology: More than just memorable

Walter Ong asserts, in his discussion [pp 69 -71] that the heroic tradition [meaning the great works of Homer (the Iliad, the Odyssey et al)] and the great pantheon of gods of ancient mythology, specifically that of the Greeks, was an outcome of the inherent characteristics of “primary” oral culture and of early literate culture. According to this interpretation of the attributes of oral culture, oral residues include a necessary structural mnemonic component in terms of what is included in works of poetry and literature. Ong states that these works include what he has termed “…type figures, wise Nestor, furious Achilles, clever Odysseys….” that is, that these figures constitute typologies. (Ong, 2000 pp 69). It will be shown in this discussion that, these ancient works do indeed present specific “types” but that their appearance function primarily as expressions of cultural values and psychological types, which has very little to do with mnemonics.

A culture of War [1]

A culture of War [1]

It will be shown that these stories arose out of an evolutionary meshing of critical points of juncture, framing a “space” where personal & psychological history and cultural values and mythology complexly intersect. It will be demonstrated that it is not the needs of an orality based culture but the language of the Unconscious and the needs of a military based culture, that provided the impetus for the creation of the bizarre psychological types and “heavy” dramas that are portrayed in these works.

More than just a clever ruse: An ancient psychodrama [2]

The connection between psychoanalytic theory [especially Freudian and Jungian] and literature [especially ancient classical mythology] is intimate and complex, indeed among the honours Freud received in his lifetime, was the prestigious Goethe Prize for Literature (Nelson, 1963). In Freudian psychology, many of the fundamental concepts, [for example parapraxis, dreams, symptoms] have direct analogies within literary theory. Specific psychoanalytic constructs constitute a sort of involuntary language, with its own laws and logic, which serve to define and describe the operation and nature of the Unconscious, within the Freudian concept of the psyche [Orlando 1978].

Personality and History fuse together in Psychoanalysis [3]

Personality and History fuse together in Psychoanalysis [3]

Mythology and mythological analogies are fundamental and integral to the central theoretical construct of Freudian psychological theory; the Oedipus Complex, which is based upon Sophocles Oedipus Tyrannus {Morford & Lenardon, 1991]. It would be dismissive of the entire field of psycho-analysis [and of much “talk therapy”] to conclude that the roots of the frequently bizarre and strange characters from these ancient stories is driven by the need to make them memorable in the sense of easier to recall, rather than by a fusion of complex psychological and cultural values, needs and characteristics.

It has been suggested that the Iliad reveals not just the attributes and characteristics of the Heroes and the gods of the mythological world but also serves to illuminate many aspects of features of Homeric and Classical Greek culture, providing insight into the ways that the Greeks viewed or perceived themselves and their society (Armstrong, 1993).

A cast of characters expressing psychological types and cultural values [4]

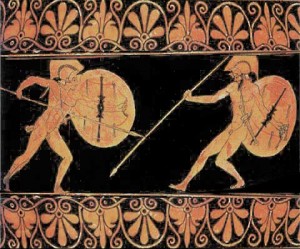

In terms of values or ethics, it is clear that within the mythical world of the Iliad, human beings are continually and dramatically playing out their predestined roles within specific well-constructed constraints, which are imposed upon their agency or range of actions, by the gods. Human beings are controlled by and subservient to, various levels or hierarchies of power [both divine and human] and domination.

Not surprisingly, in a world defined by graduations or degrees of tyranny [with the great warring kingdoms as political models], and within a story chiefly concerned with the consequences of war, the virtues [or passions] manifest in the Heroes of the Iliad [Achilles, Hector, Priam] are those that fit a military paradigm of ‘greatness’. Thus, martial values are asserted, among them, two extremely praised attributes are those embodied in the concepts of “Honour” and “Glory” defined within a specific set of military values and ethics [sic] of Greek military, partriarchical, tyranny based culture.

In summary, the story of the Iliad is clearly concerned with asserting the validity of the ‘honour culture’, which the Greeks held in such high esteem though the actions and examples of both gods and men. The power relationships between man and the divine are interactionist, that is, the same passions and character flaws plague both the Heroes and the deities. The gods participate in aspects of humanity and the Heroes participate in aspects of the divine in a complex and dialectical fashion. Nowhere in all of this, whether in terms of cultural values or in terms of psychological needs, does the role of mnemonics figure as having primacy.

Achilles: A Postmodernist Hero? [5]

Achilles: A Postmodernist Hero? [5]

Ong asserts the notion that mnemonics, and the needs of orality [as though it was in itself an entity] or of an oral based culture, are more important than the cultural values or psychological forces at play here. Ong states “…. all of this not to deny that other forces beside mere mnemonic serviceability produce figures and groupings….” and that “…psychoanalytic theory can explain a great many of these forces…”. Clearly, psychoanalytic theory and cultural forces explain the vast majority of factors at work, and mnemonic structure [like the well documented use of repetition of phrases and of whole scenarios] was a secondary, even minor attribute to these great works. The critical or primary function of these works was to support or validate cultural beliefs [representing specific values] and to express the language of the unconscious [through the representation of universal attributes] as it functions within the human psyche.

The importance of the universality of some of these values, the cultural specificity of others, and the deep psychological underpinnings of these characters and their behaviors, can be dismissed if taken at surface value. However, such surface interpretations can be misleading. These stories portray humans as being at the mercy of, or aided by, divine powers, with questions about mortality and morality often left unanswered. Indeed the great questions posed in stories like the Iliad are not resolved, and seemed shrouded forever in ambiguity.

For me these stories resonate well in our highly technical and highly literate society, even these thousands of years after they were passed down to us. These works are not merely bizarre stories from the past, made easier to remember because of their strange set of characters. Ambiguity itself is asserted within them [a very post modern concept] and functions as a sort of mythic signifier or semiotic sign, of those realities that constitute the significant and universal components of the human experience and of what it means to be human.

An eternal conflict plays out in the human psyche as well as the battlefield [6]

2 comments

1 Catherine Gagnon { 11.17.09 at 1:50 pm }

Barb, I saw your picture of the Trojan horse and was reminded of my trip to Turkey last spring, where the ancient city of Troy was actually located. I want to post 2 pictures of Troy to add to your commentary but I have to put them in a separate post on this blog. I hope you’ll check them out.

2 Clare Roche { 11.29.09 at 8:33 am }

If ound your commentary very interesting and I loved your use of pictures.

You must log in to post a comment.