The article “Does the brain like e-books” in our readings is relevant to my educational work since I deal exclusively with adult learners who are not “digital natives” (term after Pranskey, cited in Mabrito & Medley, 2008). A typical student in my online class has grade 12 education, and ages range from 18-65, with many students engaging in online constructivist collaborative learning using modern hypermedia for the first time. The typical student seems to have a period of adaptation which is required for them to become comfortable with the new skills needed for use of computer and Internet, and to develop independent self-learning and critical thinking skills.

The article “Does the brain like e-books” in our readings is relevant to my educational work since I deal exclusively with adult learners who are not “digital natives” (term after Pranskey, cited in Mabrito & Medley, 2008). A typical student in my online class has grade 12 education, and ages range from 18-65, with many students engaging in online constructivist collaborative learning using modern hypermedia for the first time. The typical student seems to have a period of adaptation which is required for them to become comfortable with the new skills needed for use of computer and Internet, and to develop independent self-learning and critical thinking skills.

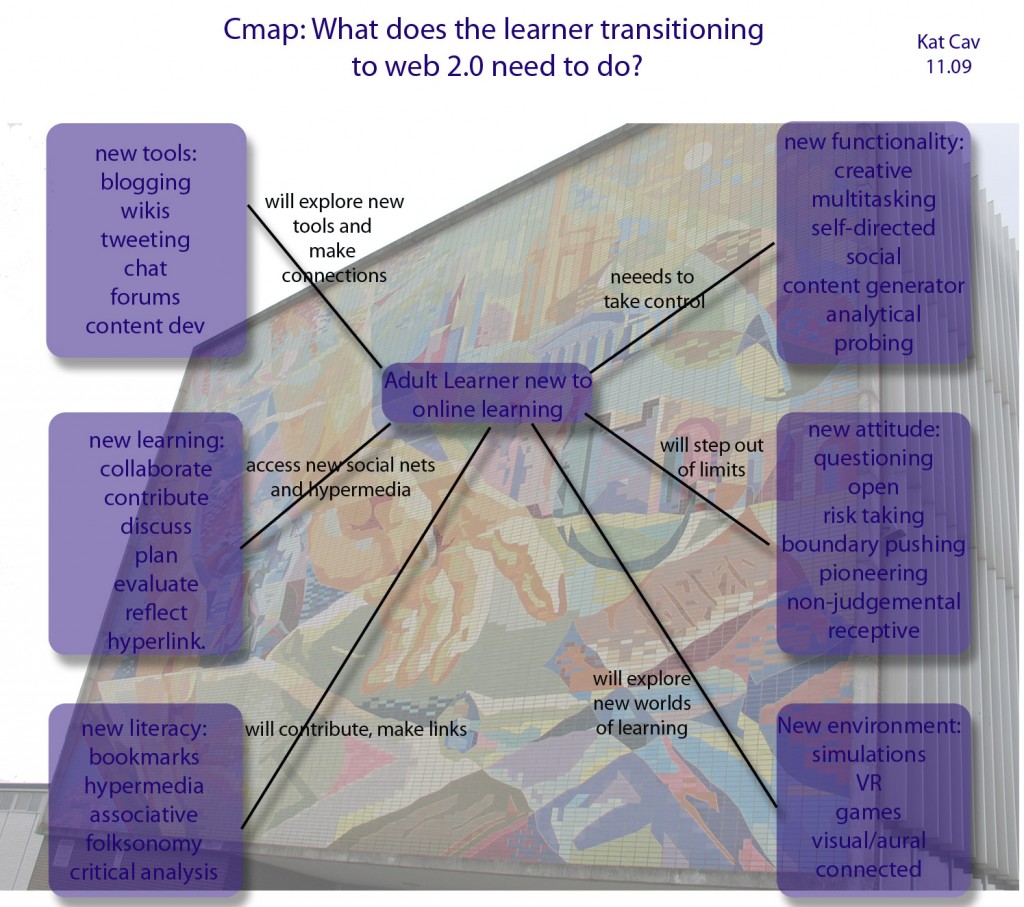

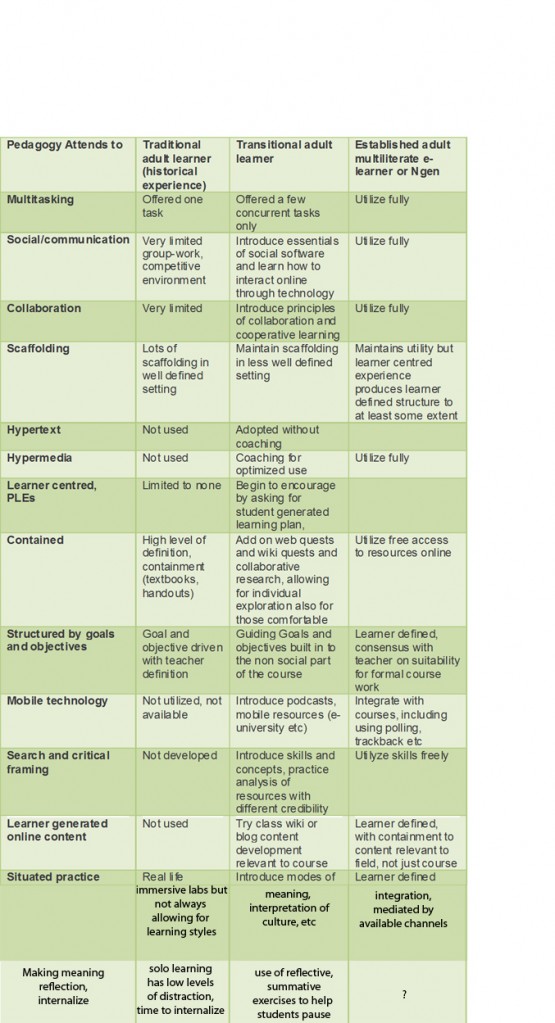

I dealt with the issue of the aspect of independent learning (learning how to learn) “the what” (after the New London Group, 1995, p 24) and its importance for students new to hypermedia in commentary #2. This commentary will focus on the learning of the content itself (the “how”, after the new London Group, 1995, p 24), and the social focus of web 2.0 learning, for students in transition between traditional literacy and learning methods, going into a web 2.0 environment. The research here will help to support or disprove my driving question of whether the transition learning period requires different pedagogy, as my daily observations seem to suggest. This subject is perhaps not as relevant for those in K-12 learning since these students are either digital natives or well versed in multiliteracy (term after the New London Group, 1996), and not faced with many first-time issues. The commentary will close with a reflective summary I developed to help understand integration of teaching initiatives outlined in the New London Group paper.

Other study groups such as Liu’s in California, the ”Transliteracies Project” (October, 2009) are shedding valuable light on this area. Liu reports “Initially, any new information medium seems to degrade reading because it disturbs the balance between focal and peripheral attention”. His observation does seem typical for newly-online learners who do in fact get sidetracked in class. Even for those adult learners with educational backgrounds, some time to adjust is required. In the MET 540 discussion forum Prizeman (2009) observes “The hypertextuality of digital writing spaced at first confused my linear mind, but now that I have spent a great deal of time interacting with them, I feel like “I’ll never go back”!” Her insight certainly reinforces the sense that there is a transitional period.

Liu (October, 2009) also concludes “It takes time and adaptation before a balance can be restored, not just in the “mentality” of the reader…but in the social systems that complete the reading environment.” This makes good sense as all literacy occurs in context, and so the student would be expected to adapt to the new way of learning in a bigger sense. Traditional pedagogy is didactic and students are used to being passive, linear and focused on one package of learning at a time as described in the Mabrito & Medley (2008) article. The Liu group confirms that in early phases of transition to new media “We suffer tunnel vision, as when reading a single page, paragraph, or even “keyword in context” without an organized sense of the whole. Or we suffer marginal distraction, as when feeds or blogrolls in the margin (”sidebar”) of a blog let the whole blogosphere in.”

The multidimensional environment calls on the learner to multitask. The open-ended resources on the Internet can be overwhelming at first as the learner enters this novel research realm. It is not the reading comprehension that suffers, as most students are adept at reading on a screen. In the “Does the Brain like e-Books?” article, Aamodt concludes, “Fifteen or 20 years ago, electronic reading also impaired comprehension compared to paper, but those differences have faded in recent studies.”

Aamodt (October, 2009) also reports that “Distractions abound online — costing time and interfering with the concentration needed to think about what you read. “ The deep concentration which is required to reflect on what is read, heard and seen may be reduced in this type of environment. Learning to focus on the work at hand and dismiss the outliers is a learning strategy that can be coached. Aamondt points out that, “Frequent task switching costs time and interferes with the concentration needed to think deeply about what you read.” Mark (October, 2009) concurs “When online, people switch activities an average of every three minutes (e.g. reading email or IM) and switch projects about every 10 and a half minutes”. That is bound to impact reflective learning. Mark also reports “My own research shows that people are continually distracted when working with digital information” so maintaining focus is confirmed to be a challenge, and her study did not just include learners new to hypermedia. She agrees with Aamondt about depth of engagement, “ It’s just not possible to engage in deep thought about a topic when we’re switching so rapidly.”

Well adapted online learners with established multiliteracy are comfortable with social networking, and multitasking in hypermedia, so more experienced learners will need more flexible environments to correlate with their skill set. Prizeman (2009) in our forums put it very well “The possibilities are endless, and the once hierarchical order that knowledge was presented in print, no longer exists in hypertext–I feel more in control of my learning, and with flexibility and freedom, I am able to search out the information that I need, as well as explore the connections between it and my world.”

The interface with online learning needs to evolve with a new appreciation of interacting with media versus human communication. Ong explores this concept and determines “communication is inter-subjective” (Ong, 2002, p 173). Ong refers to a media model of communication that focuses on informational, performance oriented interpretation, versus true communication which requires one to have advance appreciation for the other person’s inner self. That new setting is important as he points out that getting inside the minds of persons you will never know is not an easy thing to do, “but it is not impossible if you and they are familiar with the literary tradition they work in” (Ong, 2002, p. 174). Learning online does require this re-set of human communication through the window of the computer screen, and learning a new type of literary tradition, which takes time to become internalized.

Guided learning will help to address the distracting environment for transitioning students. Use of learning objectives, goal-oriented learning agreed upon by instructor and student and web or wiki quests help to direct newly-online learners to a subset of what is a large resource pool for relevant information. This limited structure is a guide not a limit. Bolter (2001, p169) points out that “relationship between the author, the text, and the world represented is made more complicated by the addition of the reader as an active participant”. A transitional learner will need to become adapted to the necessity of being more engaged and constructive when interfacing with electronic materials compared with one-way media. Use of RSS feeds can help students find key learning materials that are of high relevance. Another strategy to help a learner in that adaptation phase is to pair them with a mentor who is comfortable in web 2.0, and can be a resource for them. As well, collaborative grouping will allow students to split up a literature search or web search so that each has a self assigned area to focus in. Critical analysis of resources can be integrated with that orientation session. Some of these strategies will only be needed until new-online students’ multiliteracy is established.

The appendix table below will provide a summary of the critical pedagogy strategies that may be used to cultivate the intellect, and how they can be utilized in courses for learners of varying competence in multiliteracy.

In conclusion, it does appear that the literature supports observations that transitioning learners may need to have some early scaffolding and support and that their learning is constantly evolving through that period. Once transitioned, students can enjoy the full richness of multiliteracy and online networked learning.

A hanging issue is sparked by the observation reported by Mark (October, 2009 in “Does the Brain like e-Books?) “More and more, studies are showing how adept young people are at multitasking. But the extent to which they can deeply engage with the online material is a question for further research” Baxter (2009) mirrors these concerns when she posted “I’m not convinced that getting used to the extra activities does actually enable one to concentrate fully in spite of them. I’m more inclined to think that – along with a lot of other abilities, like amusing themselves during a power outage – the “digital generation” is losing the ability to concentrate fully on something that doesn’t engage them.”

Though these learning strategies summarized below will help us understand the transition to multiliteracy in an online learning environment, that is another realm of future enquiry; addressing the hanging issue of how transitioned students can effectively internalize and reflect on what they have learned which has been left as a question mark in the summary table.

References

Bolter, J.D. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print [2nd ed]. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

[Ed’s] Does the brain like e-books? (October 2009) featuring Liu, A., Aamodt, S, Wolf, M., Mark, G. Accessed online at the New York Times, November 1, 2009 at: from http://roomfordebate.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/10/14/does-the-brain-like-e-books

Ito, M., Horst, H., Bittani, M., Boyd, D., Herr-Stephenson, B., et al. (2008). Living and learning with new media: Summary of findings from the digital youth project. From: macfound.org , University of Southern California and the University of California, Berkeley.

Mabrito, M & Medley, R. (2008). Why Professor Johnny Can’t Read: Understanding the net generation’s texts. Innovate. Vol. 4, No. 6. Retrieved online November 1, 2009 from: http://www.innovateonline.info/index.php?view=article&id=510&action=article Page 1 of 7

New London Group (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, Vol. 66, No. 1, 60-92. Retrieved online from : http://wwwstatic.kern.org/filer/blogWrite44ManilaWebsite/paul/articles/A_Pedagogy_of_Multiliteracies_Designing_Social_Futures.htm

Ong, W. (2002) Orality and Literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Menthuen.

Prizeman, S. (2009). From Calculator of the humanist-Miller MET ETEC 540 Forum on November 23, 2009 10:34 am.

Baxter, D. (2009). From Origin and nature of hypertext-Miller MET ETEC 540 Forum on November 27, 2009 1:18 pm

2 replies on “Final project, Comment#3”

I worry that sometimes the multitasking students engage in is making them less adept at concentrating for longer periods of timeon one task.

Thanks Clare, the interesting thing is that this is an experiment really since nobody knows in advance the effects!

Is everyone seeing the table below the top cmap ok? When I just logged in again, the table is not visible in the main area but is viewable in this window? Any problems please message and I will check it–might just be gremlins at my end? Kathleen