“Few people will deny that the cinema has become one of the most powerful of influences in modern society. It is necessary, first, to recognize the twofold aspect of the cinema as an educational force. On the one hand, it is an instrument, one among many others, for achieving certain definite results: for example, the vivid presentation of facts and ideas which it is desired to impress upon children’s minds; the giving of knowledge which could be only very inadequately depicted in words or by static presentation; the representation of growth and movement; the simplification of complicated processes. It has also a second aspect: it is a method by which the human mind can be affected and directed”.

When I was searching the UBC library, I found the above sentences from Barbara Low’s article in contemporary review journal. I really liked her ideas about cinema; they seems to be correct and clear. Meanwhile, she wrote them eighty four years ago! Yes, I was also shocked when I found her article published in 1925 on the old paper. And after 84 long years, what should I add to her thoughts for Cinema?

The power of cinema is indisputable. Since the beginning of cinema, a little over a hundred years ago, it has captivated audiences. We want, badly, to watch. And this power seems unique to film. As the philosopher Stanley Cavel remarks “the sheer power of film is unlike the powers of the other arts” (McGinn, 2005).

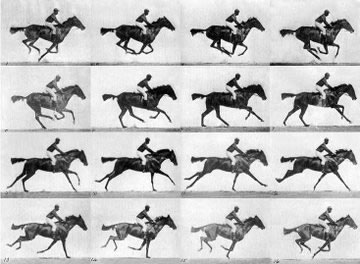

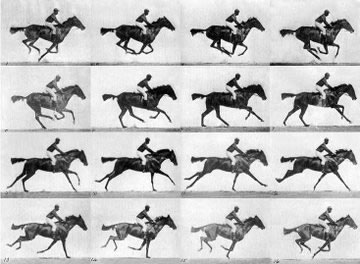

The arrival of cinema at the close of the nineteenth century immediately excited public imagination. Cinema can be considered as the illusion of movement by the rapid projection of many still photographic pictures on a screen. In fact, no one person invented cinema. In 1878, under the sponsorship of Leland Stanford, Eadweard Muybridge successfully photographed a horse named “Sallie Gardner” in fast motion using a series of 24 stereoscopic cameras. The experiment took place on June 11 at the Palo Alto farm in California with the press present (Clegg, 2007).

picture of “Sallie Gardner”

In 1893, Thomas Edison and his chief engineer Dickson successfully demonstrated the Kinetoscope, a motion picture system that enabled one person at a time to view moving pictures. Two years later, Lumiere brothers used the cinematograph to project moving photographic pictures onto a screen to a paying audience for the first time in a Paris cafe. Their machine was light, neat and versatile, serving as printer as well as camera and projector.

The standard Cinématographe Auguste and Louis Lumière

This was the beginning of a long journey. By 1914, several national film industries were established. Films got longer and story telling, or narrative, became the dominant form. As more people paid to see movies, the industry that grew around them was prepared to invest more money in their production, distribution and exhibition. Large studios were established and special theatres built (National Media Museum). In fact, the early histories of film lie in the rise of consumer culture.

Cinema has been an important means of shaping public opinion in its history. In England the Committee on Public Information produced such films as “The Kaiser: The Beast Of Berlin”, and Charlie Chaplin made several propaganda films, including one promoting British war loans. Cinema was also influential in wartime France. In 1917 Griffith filmed “Hearts of the World” in France, showing realistic battle scenes and the mistreatment of civilians by Germans, which reportedly boosted recruitment in the U.S. (Nebeker, 2009 ).

Lots of people thought that cinema could advance progress toward mass literacy. They believed that technologies such as cinema would radiate a utopian promise of ultimate democratic enlightenment. Edison, for instance, believed that cinema would bring about the perfection of education. He said that “I intend to do away with the books in the school….When we get the moving pictures in the school, the child will be so interested that he will hurry to get there before the bell rings, because it is the natural way to teach, through eyes” (Naremore, Brantlinger, 1991). In 1925, a headmaster of a school with 300 pupils, ranging from seven to fourteen years of age, stated that he has found the cinema of the highest value as an adjunct in imparting instruction in general science, geography and history (Low, 1925). He also reported “children remember what they see, though they forget what they hear.” However, the following years proofed that those initial ideas were very optimistic.

For instance, let’s consider movies’ effects in Hawaii education system. Since the 1930s, Hollywood has embraced Hawaii as a sultry paradise in film classics such as Bing Crosby’s “Waikiki Wedding”, Elvis Presley’s “Blue Hawaii” and classic World War II movies such as “From Here to Eternity”. Even today, more than 100 film and TV shows have been shot in Hawaii. Hawaii has two official state languages: English and Hawaiian. Throughout the last century as more and more Americans and British settled in the islands and developed movie industry and lots of jobs in this field were created, the everyday use of Hawaiian declined. Later, speaking Hawaiian was even seen as a deterrent to American assimilation, thus adult native speakers were strongly discouraged from teaching their children Hawaiian as the primary language in the home. This attitude remained until the early 1970s when the Hawaiian community began to experience a cultural renaissance (Grant, Bendure, 2007). It seems that, from time to time, cinema can affect process of reading/writing in an unexpected ways.

Effects of cinema on different classes of societies should not be ignored at all. Jacobs (1967) believed that the power of cinema has been a major problem of the social revolution it reflects; for one thing, to persistent pressure for restriction of content and presentation, not only for ideological purposes of control over forces of influence and persuasion, but on the part of religious, parental and educational groups concerned with effects upon the young.

In England, in the majority of 1950s war films, the role of middle class of society in winning the war was heavily emphasized. The main reason was due to fear that middle class of society had an alliance between upper class and worker class. The great Victorian invention, the middle class, had always affected to despise both these other classes, although remaining ready to allow the upper class to rule and the working class to work as long as its own class position as backbone of England, remained undisturbed. The promises made or implied by a people’s war seemed to offer consolidation of that position and to have improved along with improving the conditions of working class (Dixon, 1994).

According to Bolter’s (2001) concept of remediation, each technology claims to be superior to the one it sets out to remediate. This was also valid for cinema. In 1930s in Soviet Union, Stalin began to perfect the techniques used by Lenin in the civil war of deploying non literary modes of mass propaganda. Soon it followed more effectively by the fascist regimes in Italy and Germany, learned how to use the inventions of new century to solve the problems of the old. The dark forests of oral communication, which 19th century governments had sought to open up with the written word, were now invaded by devices which bypassed print altogether. Later as some kind of peace was achieved, so the technological developments of the era, especially the cinema, were pressed into the service of the totalitarian state (Vincent, 2000).

According to Henderson (1992), cinema and its effect on the rise of a celebrity-based culture in this century can in part be attributed to America’s change-over from a producing to a consuming society. It also has to do with the shift in our cultural perspective that occurred in the late nineteenth century. The essential power of the cinema lay in its specificity. Cinema is both the space of isolation and the space of shared experience and its presence in our culture is significant (Harvey, 1996).

Power of cinema can also affect cultural identities of youth and young adults in different societies. In the mid 1950s, the gradual relaxation of the Hollywood production code and the growth of independent filmmaking brought to the forefront a whole series of American movies which openly explored taboo breaking subjects about sexuality, crime, and the use of drugs. One series of movies causing a heated public controversy dealt with the social problem of juvenile delinquency. Films like The Wild One, with Marlon Brando in 1953, directly confronted the issue of postwar youngsters’ crime and gang life, initiating cycles of teenage exploitation films often called juvenile delinquency movies.

In the U.S., these successful film cycles about the misbehavior of rebellious post war baby boomers sparked a wider controversy about the increase in juvenile crime, the failing educational system, and the loss of family values in American society. The movies only increased the anxious inquiries from different parts of the society. What is so interesting about these 1950s juvenile delinquency movies is that they could stir up such a heated debate across various groups and organizations. Everyone from the average audience to the U.S. Senate, including leading journalists, intellectuals, politicians, and religious leaders, was moved to raise their voices about these movies’ effects on endangered core social values. This situation, where various moral guardians express their concern over key values, often signals a society wide moral panic. The controversy and moral panic were not restricted to the U.S. In the U.K. and other European countries, a wider public debate addressed juvenile delinquency and the influence of imported American movies (Biltereyst, 2007).

Despite a century of development cinema, with a huge industry, is still a young event. Cinema was not invented. Nor was it precisely a process of evolution. Rather it was the realization of a conception that had been clearly envisioned for centuries before. Edison, Dickson, Paul, the Lumieres merely chanced to be the ones privileged to add the last elements to the building that had been foreseen and in the making for many generations (Robinson, 1996). Perhaps, it is better to say that movies are not documents of their time; they are feelings of their time. Its effects on culture, reading/writing, mass literacy, politics of the societies can not be ignored. In general, emerge of cinema at the end of the nineteenth century initiated a movement from text culture to visual culture societies.

Let me finish what I started with some sentences from Barbara Low (again!) about cinema written eighty four years ago. “It is, therefore, very much worth while to consider to what extent this extremely powerful force of the cinema may help or intensify different attitudes”.

References

Biltereyst, Daniel. American juvenile delinquency movies and the european censors, in youth culture in global cinema, edited by Timothy Shary and Alexandra Seibel, University of Texas press, Austin, 2007.

Bolter, Jay David. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print [2nd edition]. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Clegg, Brian (2007). The Man Who Stopped Time. Joseph Henry Press.

Dixon, W. Winston. Re-viewing British cinema, 1900-1992, State University of Newyork Press, Albany, 1994.

Grant, K. Bendure, G. Hawaii, Lonely Planet. 2007.

Harvey, Sylvia. (1996). What is cinema?, in Cinema: the Beginnings and the future, edited by Cristopher Williams, University of Westminster press. London.

Henderson, Amy, (1992). Media and the Rise of Celebrity Culture. OAH Magazine of History, Spring 1992.

Jacobs, Lewis. The rise of the American film. Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, 1967.

Low, Barbara. (1925). The Cinema in Education: Some Psychological Considerations. Contemporary Review, November, 1925.

McGinn, Colin. The power of Movies. Pantheon Books, New York, 2005.

National Media Museum. http://www.nationalmediamuseum.org.uk/pdfs/cineHISTORY.pdf

Naremore, James. Brantlinger, Patrick (1991). Modernity and mass culture, Indiana University Press, 1991.

Nebeker, Frederik. Dawn of the electronic Age: Electrical Technologies in the Shaping of the Modern World. John Wiley & Sons. Newjersy. 2009.

Robinson, David. (1996). Realising the vision: 300 years of cinematography, in Cinema: the Beginnings and the future, edited by Cristopher Williams, University of Westminster press. London.

Vincent, David. (2000). The rise of mass literacy: reading and writing in modern Europe. Pility Press, UK.

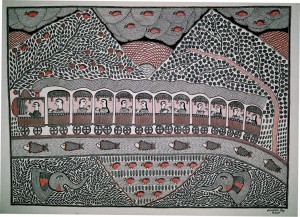

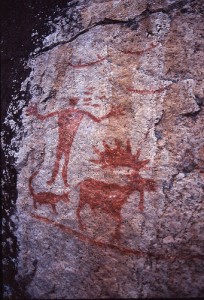

Long before there were computers in most of our homes, there was Mithila Art in homes of what is now India and Nepal. Originally, this folk art form mainly consisted of lively murals painted on the walls of homes in rural villages. But it was much more than simple art for art’s sake. “Mithila painting is part decoration, part social commentary, recording the lives of rural women in a society where reading and writing are reserved for high-caste men” (Arminton, Bindloss & Mayhew, 2006, p. 315). This was art that gave a voice to powerless rural women as a communication technology.

Long before there were computers in most of our homes, there was Mithila Art in homes of what is now India and Nepal. Originally, this folk art form mainly consisted of lively murals painted on the walls of homes in rural villages. But it was much more than simple art for art’s sake. “Mithila painting is part decoration, part social commentary, recording the lives of rural women in a society where reading and writing are reserved for high-caste men” (Arminton, Bindloss & Mayhew, 2006, p. 315). This was art that gave a voice to powerless rural women as a communication technology.