Please see “The History of the Study of Grammar” in the class wiki and follow the links

ETEC540/2010WT1/Assignments/ResearchProject/StudyofEnglishGrammar

Tamara Wong

Please see “The History of the Study of Grammar” in the class wiki and follow the links

ETEC540/2010WT1/Assignments/ResearchProject/StudyofEnglishGrammar

Tamara Wong

In his 1945 paper “As We May Think,” Dr. Vannevar Bush made many accurate predictions about future technologies. Bush suggested that cameras could be as small as walnuts, they would automatically adjust the exposure to the light in the room, the lens would be of universal focus, there would be film for over 100 pictures, and they would only need to be wound once. Bush also predicted that “the Encyclopaedia Britannica would be reduced to the volume of a match box,… material for [it] would cost a nickel, and it could be mailed anywhere for a cent” (p. 4). Even Bush’s prophecies about “the author of the future talk[ing] directly to the record” (p. 5) have been realized, with speech to text and text to speech programs.

Although many of the predictions made throughout “As We May Think” have come true, there is one major prediction that has yet to occur. Bush believed that a machine would be built that would extend human intelligence and memory by giving the user easy and rapid access to vast quantities of information, or “the record.” This hypothetical machine was given the name Memex. According to Bush, science was at a precarious time, because “publication [had] been extended far beyond [their] ability to make real use of the record” (p. 2). He felt that for a record “to be useful to science, [it] must be continuously extended, it must be stored, and above all it must be consulted” (p. 3). Bush was afraid that “truly significant attainments [in science would] become lost in the mass of the inconsequential” (p. 2). His machine was the answer to this problem.

The Memex was to look like a desk, with all of the information stored on microfilm. The user would tap in a code corresponding to the book that he wanted to read, and the Memex would project the pages of the book from the microfilm onto the desktop. The user would be able to add notes, pictures, or other memorabilia to his book via a camera built into the Memex, and he would also be able to purchase other microfilm to add to his Memex so that the information would be current.

The defining feature of Bush’s creation was that it mimicked the human thought process, by enabling the user to pull up information by association. In his paper, Bush states that the human mind works by association, and that “our ineptitude at getting at the record is largely caused by the artificiality of systems of indexing” (p. 9). With the Memex, “any item may be caused at will to select immediately and automatically another. This is the essential feature of the Memex, [because] the process of tying two items together is the important thing” (p. 10). For example, a person may be

“studying why the short Turkish bow was apparently superior to the English long bow in the skirmishes of the Crusades. He has dozens of possibly pertinent books and articles in his Memex. First he runs through an encyclopaedia, finds an interesting but sketchy article, and leaves it projected. Next, in a history, he finds another pertinent item, and ties the two together. Thus he goes, building a trail of many items. Occasionally he inserts a comment of his own, either linking it into the main trail or joining it by a side trail to a particular item. When it becomes evident that the elastic properties of available materials had a great deal to do with the bow, he branches off on a side trail which takes him through textbooks on elasticity and tables of physical constants. He inserts a page of longhand analysis of his own. Thus he builds a trail of his interest through the maze of materials available to him” (p. 11).

Unlike human memory, this trail would never fade, and the user could pass his trail on to another Memex owner. In later versions, Bush’s Memex would even build trails by itself, by recognizing keywords in different articles, and tying those articles together for the owner (Bush, 1967).

In theory, this sounds like a remarkably useful machine, which begs the following question. With so many of Bush’s other foresights coming true, why has this seemingly brilliant idea never come to fruition? The cost of building a Memex, which Bush felt was the major roadblock for a real life installment of his machine, is no longer an issue in the present day and age. Bush’s (1967) other concerns of gross information storage and rapid access have also been rendered moot by digital computing, so why is a modern equivalent of Bush’s Memex not available for purchase?

Part of the problem is that the Memex was a personal memory support, not a public database in the sense of the modern internet (Barnet, 2008). The potential for collaboration is much greater in a public database than in notes and “trails” passed amongst a few highly regarded experts. This is evidenced by the emerging success of Wikipedia over Britannica or Encarta. In addition, a public database has a much wider economic market than a purely academic personal aid.

However, an even larger flaw in Bush’s reasoning may have been the assumption that because his machine mimicked human thought, it was automatically better than a system that did not mirror the human brain. According to Ong, technology does not have to emulate human thought to be effective. Ong (2002) states that “technologies are artificial, but… artificiality is natural to humans. Technology, properly interiorised, does not degrade human life but on the contrary enhances it.”

Further support that mimicry is not crucial for technology to be effective is provided by Barnet (2008). In her examination of the Memex, Barnet indicates that Bush was uncomfortable with digital electronics as a means of storage, as “the brain does not operate by reducing everything to indices and computation.” Bush did not realize that digital electronics could operate unseen to the user, and serve the same function as the actual mechanism he proposed would physically retrieve and display the microfilm. However, digital electronics would hold millions of books, and they would allow users to search through all of those books extremely quickly – both qualities that Bush strove for in his Memex.

In the spirit of Bush’s 1945 article, I will make a prediction about what his Memex may look like, some time in the distant future. The Memex will be a tiny microchip, or network of microchips implanted in your brain and along your brain stem, that can completely and unobtrusively interface with your thoughts. You won’t be able to feel it, and you’ll never notice it, but it will allow you to perfectly memorize an entire book and flawlessly remember every conversation you ever had. You will be able to remember what you had for lunch 37 years, 45 days, and one hour ago, as if you just finished your lunch an hour ago.

This Memex will work by “recording” the electrical impulses as they run to your brain when you watch a TV show, or touch a piece of fur. If you wanted it to, the microchip could re-send those same electrical impulses to your brain, and you would see EXACTLY what you saw when you first watched the show, and feel exactly what you felt when you first touched the fur. In other words a perfect memory would be recreated.

You could go on vacation, and your implant would record every electrical impulse that goes shooting up to your brain. You could then wirelessly send that record to some friends, and they could re-live your entire vacation. Every sight, smell, sound, texture, and taste that you experienced would be replayed as a set of electrical impulses from their implants to their brains, and it would all happen from the comfort of their own homes.

To some, this prediction may seem far fetched and unlikely. Those skeptics may agree with Bush (1945), who felt that “prophecy based on extension of the known has substance, while prophecy founded on unknown is only a doubly involved guess,” so I will leave you with a few articles to peruse, should you happen to have the time.

http://www.robaid.com/bionics/controlling-a-robot-arm-with-your-mind-even-a-monkey-can-do-it.htm

http://www.physorg.com/news194796581.html

References

Barnet, B. (2008). The Technical Evolution of Vannevar Bush’s Memex. Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne. Retrieved October 26, 2010, from http://digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/2/1/000015/000015.html#nyce1991

Bush, V. (1967). Memex Revisited. Retrieved October 26, 2010, from http://courses.kathiegossett.com/pdfs/bush_memexrevisited.pdf

Bush, V. (1945). As We May Think. The Atlantic Monthly, 176(1), 101-108. Retrieved October 25, 2010, from http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/194507/bush

Keep, C., McLaughlin, T., & Parmar, R. (2000). The Electronic Labyrinth: Vannevar Bush. Retrieved October 25, 2010, from http://www2.iath.virginia.edu/elab//hfl0034.html

Nelson, T. (1999). Xanalogical structure, needed now more than ever: Parallel documents, deep links to content, deep versioning and deep re-use. Retrieved October 25, 2010, from

Ong, W. J. (2002). Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London and New York: Routledge.

Just a note before beginning!

Even though plenty of literature available on studies on the relation of technology and cultural changes, I didn’t have much success on trying to find scholarships related to the impact of the printing press in the Renaissance in the 15th century, Italy until I read Elizabeth Eisenstein ’s book “the Printing Press as an Agent of Change” Therefore, I was not surprised when Eisenstein (1979) states that the advent of printing and fifteenth century cultural change has not been explored yet.

Renaissance Humanism in the 15th century, Italy

One of the most important aspects of the Renaissance in the fifteenth century in Italy was the Humanism which refers to the return of the classical Greek. At that time the humanist movement was a success on the cultural stage. The humanists were more in tune with the intense Christian Renaissance society than other cultural movements. The Christian Petrarch and his followers achieved a high position for themselves and for the studia humanitates. It is known that they were wealthy, powerful and intellectual people. But historians such as Seigel (1968) argue that their place in the life of Renaissance Italy is arguably more complex than it seems. One of the arguments is related to the humanists’ prestige, which exceeded that of the medieval dictatores (Gray, 1963) that may have influenced in the fading of the scholastics’ popularity.

Renaissance Humanism permeated through the fifteenth century, but it was not replacing medieval scholasticism. Literature shows that there was still a strong interest in scholastic philosophy. At the beginning of the century both of the two have their own place in the intellectual life of the time. While the humanists often succeeded in gaining the available university chairs in moral philosophy for themselves; the scholastics obtained theirs in logic. Humanism and scholasticism shared men’s attention inside as well outside of the universities.

The Renaissance humanists believed that education should equip a man to lead a good life and knowledge was not merely to demonstrate the truth but to impel people toward its acceptance and application. They believed a man could be molded through ‘the art of eloquence’. They implied an almost incredible faith in the power of the word (Gray, 1963). Many Italian scholastic philosophers and theologians encouraged a positive attitude toward civic and practical life and opened the door for science as well.

For Petrarch and his successors, Cicero’s oration Pro Archia was a sacred text. Gray (1963) argues that the pursuit of eloquence joined humanists of all shades; and to ignore the impact of eloquence and the ideas associated with it is to distort the mentality of humanism and disregard a vital dimension of Renaissance thought and method as well.

To this extent, Eisenstein (1979) adds that there was evidence that the humanists mentality lacked modern perspective because they were focused on ancient poets belonging to a remote pre-Christian context.

The advent of the printing press

Since the invention of the press western culture lost its medieval characteristics and became distinctively modern. It was a shift from the hand written book to the printed one. The name most associated with the press is Johannes Gutenberg (1397-1468) a German goldsmith whose great invention was not exactly the printing press, but the creation of movable, variable-width, metal type.

Petrarch’s revival of Cicero’s rhetoric was flourishing in Italy in the age of the hand-copied books. The book culture did not change much with the advent of the printing press. While there was no encouragement of the spread of the new technology, the advent of the press may have forced manuscript bookdealers, such as Vespasiano, to close their shops.

On the other hand, Eisenstein (1979) argues that from the view point of most Renaissance scholars, the advent of the printing came too late to be taken as a point of departure for the transition to a new epoch. They believed it began with the generation of Giotto and Petrarch before Gutenberg. It was believed this technological and cultural change did not indeed concern the major cultural changes that had occurred under the auspices of scribes. Eisenstein (1979) remarks that the Italian Renaissance underwent a mutation after the advent of printing, but it does not mean that there was nothing else that may have affected the Renaissance before this event.

But, what is the relation of the revival of rhetoric and the changes introduced by printing needs? Eisenstein (1979) mentions that in ‘The history of the book’ published by UNESCO Vervliet states: “It is not so much that printing made the Renaissance possible as that the Renaissance contributed to the successful spread of printing’. Did printing make Petrarchan revival possible? How? How did the Renaissance contribute to the spread of printing?

Eisenstein (1979) argues the persistence of the notion that printing came as ‘by-product of the Renaissance spirit.’ What was the spirit? In fact the first attempt to use the benefits of the printing press as new medium to arouse widespread mass support was not in connection with Italian humanism but with a late medieval crusade, which was the war against the Turks.

It is difficult to establish the impact of the printing press in its first century especially on a very conservative and religious society. The scribal culture revered the ancients because they were closer to uncorrupted knowledge, which was not yet corrupted through the process of scribal transmission (Dewar, 2000). It had to pass a full century before the outlines of a new world began to emerge.

Eisenstein (1979) argues that by 1500 various printed materials were already being registered. But, the number of books produced was not much different from the number produced by scribes.

In Education

The impact of print on education may have been hidden or delayed since it could have no effect on unlettered folk; it affected only a very small literate elite recording more sermons, orations, adages and poems in order to serve the needs of preachers and teachers pursuing traditional Christian ends.

By the time a new approach in education had emerged it was called “New Learning” . It sought to learn from classic texts that the medieval texts did not address, but without challenging the Christian belief.

Reference:

Dewar, J. (2000). The information age and the printing press: Looking backward to see ahead. Retrieved from: http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=347634.348784archive Volume 2000.

Eisenstein, E. (1979). The Printing Press as an Agent of Change: Communication and cultural transformation in early modern Europe. (2 Vol.) UK: Cambridge University Press.

Gray, H. (1963). Renaissance Humanism: The pursuit of eloquence. Journal of the history of ideas, Vol 24, No. 4, pp.497-514.

Seigel. J. (1968). Rhetoric and philosophy in Renaissance humanism: The union of eloquence and wisdom, Petrarch to Valla. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

In western educational systems of today, children are taught to read much the same as they have been taught to read for decades. Generally speaking, children are taught to read phonetically, breaking words down into their sounds (individual letter sounds and digraphs, of which there are 42 sounds in the English language), they are taught to recognize ‘tricky words’ (such as ‘the’) that cannot be sounded out phonetically, and they learn to read first out loud, and then silently and independently to themselves. Many aspects are assessed when children first learn to read, such as comprehension and fluency, as well as knowing what to do when encountering punctuation in the texts read. However, being able to read silently and independently is the ultimate goal. Indeed, silent reading is so important in the western educational system that parts of every school day are devoted to it (particularly in younger grade levels), with popular programmes such as Silent Sustained Reading (SSR) and Drop Everything and Read (DEAR) being two of the more common. The purpose of this paper is to look at the origins of silent reading and the influence it has had on reading programmes today in western education systems.

The origins of silent reading are not exactly precise, neither our knowledge of early print and text literacy a thorough, detailed, historical account. We do know that early, pre-text society was an oral-aural one, where information and knowledge were passed through word of mouth, often in rhyme or song (for lengthy accounts), with repetitive elements so that it could be remembered easily by the orator. Written text was first developed among the Sumerians in Mesopotamia around the year 3500 BC (Ong, 2002). By Plato’s time however, written text had become the new way of storing knowledge, allowing for less repetitive thought (Ong, 2002).

Though written text (manuscripts) had become the new way of storing knowledge, it was still originally written to be read aloud, either to others or to oneself (among other people), with little or no punctuation as we would recognize it today (Ong, 2002). It was not until much later that we see recorded accounts of people reading silently to themselves and in these accounts the writers are often surprised to be witness to such events. In AD 383, in the first recorded instance in Western literature, Saint Augustine wrote of Ambrose, “we found him reading like this in silence, for he never read aloud” (Manguel, 1996). Further instances can be seen in plays from the 5th Century BC from Euripides and Aristophanes, with both having characters read items silently and then react to them. (Manguel, 1996).

With the development of the written word came the intimacy of the author with his work. In the fourteenth century authors began composing texts in cursive script, making the text and writing a more intimate affair. With this intimacy of the author came the expectation that it would be read with intimacy, or independently and in silence to oneself (Saenger, 1997). In the centuries to follow, throughout the Middle Ages, silent reading began to work its way into education. Scholarly libraries began to be developed where reference books were chained to lecterns so that they would always be consulted in the library (Saenger, 1997). From these libraries the first instances of a need for the reader’s silence was made note of and this has continued through to libraries throughout the world today (both academic as well as public), as we know them.

Why was there a delay in the move from reading text aloud to reading silently? Early manuscripts were written to be read aloud and did not include punctuation in any way as we know it today. Punctuation as we know it today can be defined as “the practice or system of using certain conventional marks or characters in writing or printing in order to separate elements and make the meaning clear, as in ending a sentence or separating clauses” (dictionary.com). With the development and beginning widespread use of print, as well as the development of the printing press, punctuation started to be used more widely and uniformly in order for people to make meaning of what they read easier and quicker. In addition to punctuation being added to print, so too did proper spacing between words and sentences, as well as paragraphs begin to be seen.

While there has been well documented impact on religious and political fronts over the early years of silent reading, of which I will not even attempt to go into here, there has also been great impact on education, especially in the last few decades. Being able to read silently and with comprehension and fluency is the goal of western language programmes and students are routinely tested on their ability to glean information from text without uttering a word.

Schools continue to spend valuable time every day, devoted to individual, silent reading programmes. These programmes, often called Silent Sustained Reading (SSR), Drop Everything and Read (DEAR) or something similar, are enforced based on the belief that the more often children and young adults read silently, the better they will become at reading in general (mentality of practice makes perfect perhaps). Silent reading is thought to instill a love of reading in children, increase comprehension and fluency and, often of most importance, speed of reading (Surrey School District). There is little supported evidence however, that silent reading programmes in schools are all that effective. One has to wonder how much time has been spent on a daily event that shows few dividends.

It is difficult to imagine what a library would be like today if everyone were not reading silently, or similarly what a coffee shop or metro station would be like. We are taught to value finding a comfortable nook to curl up in with a good book. Oral reading has become a lost art of sorts, with students able to be kept captive while listening to a gifted story-teller. Silent reading has made learning individual in many ways. Though one could always read orally to oneself, silent reading promotes individual, silent reading by its very nature.

References

Bolter, Jay David. (2001). Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the remediation of print. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates (digital copy purchased from Amazon.com)

Manguel, Alberto. (1996). A History of Reading. New York: Viking. Retrieved from http://www.stanford.edu/class/history34q/readings/Manguel/Silent_Readers.html

Ong, Walter. (1982). Orality and Literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Methuen (digital copy purchased from Amazon.com)

Saenger, Paul. (1997). Space between words: the origins of silent reading. Palo Alto, Stanford University Press.

Silence is Not Always Golden: Examining Research into Silent Reading. Research Currents, Surrey School District. Retrieved from http://www.sd36.bc.ca/general/research-eval/researchcurrents/silentreading_vol2.pdf

Punctuation. In Dictionary.com. Retrieved November 6th 2010 from http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/punctuation

Sustained Silent Reading. Retrieved November 6th 2010 from http://wik.ed.uiuc.edu/index.php/Sustained_Silent_Reading

Assignment 3 (Research Topic)

As an educator a great emphasis in my own recent professional growth and learning has been in the area of technology literacy and preparing the 21st century learner for a 21st century world. There is, of course, a challenge and considerable debate in defining exactly what those glittering terms mean and the knowledge and skills required of the ‘21st century learner.’ Further, at times, getting to the deeper understanding, clarification, and meaning of such terms and concepts are left unquestioned because it is implied, from those who promote and demand such an educational focus, that these essential learnings are the only route to student success in a modern age. For educators who are mindful of the broader implications of the role of technology and technological literacy in their practice with students it is important to question and critically assess whose interests are best served in the development of curriculum to meet 21st century technological literacy standards. That varying interests are being served in this process speaks to the underlying politics that are attached to all technological advancement. Therefore, considering the politics embedded in the evolution of print technologies and mass literacy, from a historical perspective, can help with critical reflection on the current shift in technological literacy. As well, by examining more closely the promotion and development of mass literacy, parallels can be drawn to how technological literacy is being promoted in current educational environments.

One aspect of mass literacy, through print based and digitally based technologies, that helps to inform educators and others is to consider the position of literacy between perspectives of equality and dominance. Put another way, we must be cognizant of whose interests are best being served by the form, content, and control of the literacies being introduced and promoted. Throughout the literature exploring the political ramifications of mass literacy researchers uncover and draw attention to the power relations that are often attached to the diffusion of literacy within a society (Ong, 1982; Ohmann, 1985; Rockhill, 1987; Collins; 1995; Petrina 2000; & Wingrove, 2005). Ong (1982), for instance, explores the onset of literacy in scribal cultures where written literacy was often restricted to specific sub-groups in a culture. Evidence emerges positing that, as the printing press appeared and scribal technologies gave way to print technologies, a cultural/social bias emerged from those who had the needs and means to develop the technology and distribute print based texts.

Threading through the research then, are a few dominant cultural perspectives that pervaded early (and late?) mass literacy movements through print based text. Firstly, in their work Rockhill (1987); Wingrove (2005) and Collins (1995) all explore concepts of gender dominance in print based texts. Rockhill (1987) draws the general conclusion that mass literacy, in male dominated public literate worlds, has been central to the gendering of a society and resulted in the oppression and social exclusion of women. In her rhetorical analysis of the writing of Mary Wollstonecroft, Wingrove (2005) explores the complex gender politics of 18th century print culture. For her part Wingrove acknowledges gender biased identities cultivated in literature, yet suggests that understanding the impact of that literature on the public sphere of women is difficult to determine. Collins (1995), like Rockhill, is more categorical in his position on the social power relations embedded in mass literacy and posits that historically literate discourse has supported traditional idea of males in public power based roles and female in private domestically based roles. Regardless, that power relationships and cultures of dominance have been cultivated through the onset of mass literacy is clearly evident in the literature on the subject.

In addition to gender politics, it is the role that the state or other controlling interests, such as an economic elite, have in the promotion or restriction of mass literacy where the politics of literacy is most evident. Who should and should not be literate?, Who should have access or be denied access to printed text? Who needs to or needs not to be able to read? These are questions that are often directly determined by the state or indirectly answered by controlling power structures in a society. Historically, literacy is situated in dichotomous positions determined by the controlling power structures of the state or culture. For instance access to texts, as the necessary basis for literacy, is often divided like other socio-economic structures into have and have not hierarchies. Ong (1982) discusses pre-print, clergy dominated, societies where the manuscripts and were the sole domain of the religious authority. Similarly, with the advent of print technologies and various forms of state authority through the 18th and 19th centuries cultures of dominance were supported by ruling elites who felt that mass literacy was not desirable. Indeed, keeping second or underclass citizens (subjects) ignorant was a goal of the powerful ruling classes. Concentrating the literate class and cultivating a state which denied access to literacy among large populations of underclass citizens was a common theme for many states which feared putting knowledge in the hands of those beneath them. That literacy could serve as a mechanism for social disorder and dissent was motivation for autocratic states to concentrate and control access to printed text (Collins, 1995; Ohmann, 1985; & Ruud 1981).

Contrastingly, in her comprehensive work, on the impact of the printing press, Einstein (1968) acknowledges that while power and access did often concentrate in the hands of the ruling religious, monarchical, and despotic elites for a time, eventually with the diffusion of print based texts this power structure was transformed and broken down. Further, she asserts that as mass literacy emerged and entrepreneurs took the lead on printing texts traditional power relations were broken down as the rise of scientific thought and philosophy was diffused to the growing literate classes. Likewise, Ruud (1981) chronicles the role of the printing press in supporting revolutionary change in Russia at the beginning of the 20th century.

The evolution and eventual diffusion, in many societies, of print from written manuscripts to mechanical print, via moveable type, had a profound effect on what is termed ‘literacy.’ Indeed, many would suggest that the innovations in mass print technologies and the growing collection, access, and distribution of mass print based resources has resulted in improved literacy. At the same time, critical reflection on what exactly constitutes literacy sheds light on the pervasive politics and power relations that surround the uses of literacy in maintaining and legitimizing power. Further, state interventions to solve and respond to literacy issues reflect the underpinning politics and social power relations that are at interplay at any given point in time. In his 1985 work exploring Literacy, Technology and Monopoly Capital, Richard Ohmann, articulates how the rates of literacy vs illiteracy are used and manipulated in a political policy context to support social order among the poor and perpetuate the prosperity and stability of the economic elite. Roberts (1995) carries this further and highlights how defining literacy has come to be profoundly a political question where the meaning and measurements of literacy are constantly shifting to meet political agendas. These agendas include efforts by the state to be seen to be improving literacy rates where they are perceived to be lacking, supporting and being in control of policy decisions, developing educational strategies supportive of state goals, and seeking conformity to a desired social order.

Apart from and connected to the idea of literacy vs illiteracy is the consideration of types of literacy. Since the onset of mass distribution of print technologies defining who is literate has centered on being print literate in the vernacular of the majority culture. Thus, policy decisions, have often neglected to address the issues of multiple literacies where, for example, being literate in spoken word and public spheres is as necessary for economic security as being literate in written language. Collins (1995) frames this as the cognitive cultural Great Divide and points to how such gaps enter the political sphere as governmental and non-governmental organizations attempt to bridge these such divides through public policy.

Another consideration that deserves attention when exploring the politics associated with mass literacy comes back to the idea of whose interests are best being served in the production, distribution and internalization the printed texts that support ‘mass literacy.’ As mentioned previously, those who had the means and needs to further the development of print technologies did so for their own purposes and manufactured products that reflected their particular world-view (Collins, 1995; Einstein, 1969, Ohmann, 1985; Rockhill, 1987). Einstein (1968) draws attention to the loss of specific vernaculars as printers standardized text that supported the vernacular of the elite. More recently, in her work, Rockhill (1987) argues how the state attempts to detach literacy from embedded ethnocentric power relations when policy is made to deal with issues of illiteracy. By highlighting the fact that the majority of those classified as illiterate are linguistic minorities and women she makes the fundamental argument that illiteracy continues to be supported by neglect of the dominant culture who controls the means of production. Considering these brief examples of whose interests are being brought forward through mass literacy and the preceding discussion of dominant cultural perspectives, and power relations embedded in print based technologies we now return to how this can be used to inform educational philosophy in the area of technological literacy.

Great divide theories have been touched on above as many researchers frame issues of literacy in this context. Divide theories are also explored in the area of technological literacy where it is suggested that technologies developed from a dominant cultural perspective perpetuate an environment where some experience political and economic power while others are left out (Chandler, 1994; Postman, 1992; & Petrina 2000). Chandler (1994) and Postman (1992) make convincing arguments that refute neutrality and confront embedded power relations inherent in technology design and production. Thus, support the ideas that being technologically literate in such an environment cultivates the values of some perspectives over others. Cautioning educators to be critical in their use interactions with technology and the potential interests that are being served by that use, Petrina (2002), challenges educators to ask themselves crucial questions as they infuse technology and attempt to meet the needs of 21st century learners:

Are you prepared to teach both the ‘applications’ and ‘implications’ of this technology? Can you demystify it and resensitise your students to its political implications? Are you familiar with the politics of this technology? How will you prepare resources that deal with the politics of these specific small ‘t’ technologies as well as big ‘T’ Technology? (Petrina, 2002: 36)

At the very least being mindful of the underlying political interests that have threaded their way through the evolution of print culture and the push toward mass literacy help to inform educators as they seek to assist all their students in acquiring an equitable 21st century digital literacy that will not leave some marginalized while others flourish.

References

Chandler, D. (2000). Technological or media determinism. Retrieved fromhttp://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/tecdet/tdet01.html

Collins, J. (1995). Literacy and literacies. Annual Review of Anthropology. AnnualReviews. (24). 75-93. Retrieved October 12, 2010 from JSTOR database: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2155930

Einstein, E. (1968). Some conjectures about the impact of printing on westernsociety and thought: a preliminary report. The Journal of Modern History, (40)1. 1-56. Retrieved October 12, 2010 JSTOR database.

Ohmann, R. Literacy, technology, and monopoly capital. College English. (47) 7. 675-689. National Council of Teachers English. Retrieved October 12, 2010 JSTOR database: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1392734

Ong, Walter. (1982.) Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Methuen.

Petrina, Stephen. (2002) 2020 vision – on the politics of technology. Design & Technology – for the next generation. ETEC 511 Course materials. From https://www.vista.ubc.ca/webct/urw/lc5116011.tp0/cobaltMainFrame.dowebct

Petrina, Stephen. (2000) The politics of technological literacy. International Journal of Technology and Design Education. Kluwer Academic Publishers (10)2. Retrieved October 10, 2010 from http://www.springerlink.com/content/xj23615727k48058/

Postman, N. (n.d.). Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. New York, NY: Vintage Books

Roberts, P. (1995). Defining literacy: paradise, nightmare or red herring? British Journal of Educational Studies. Blackwell Publishing. (43)4. 412-432. Retrieved October 28, 2010 from JSTOR database: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3121809

Rockhill, K. (1987). Gender, language and the politics of literacy. British Journal of Sociological Education. (8)2. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Retrieved October 4, 2010from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1392734

Ruud, C. (1981). The printing press as agent of political change in early twentieth-century Russia. Russian Review. Blackwell Publishing. (40)4. 378-395. Retrieved October 26, 2010 from JSTOR database: http://www.jstor.org/stable/129918

Wingrove, E. Getting intimate with wollstonecroft: in the republic of letters. Political Theory. Sage Publications, Ltd. (33) 3. 344-369. Retrieved October 12, 2010 from JSTOR database: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30038424

During the late 1970s and early 1980s Elizabeth Eisenstein wrote extensively about the revolution that occurred after the invention of print and termed it the ‘Unacknowledged Revolution’ as she felt it had been overlooked. The printing press gave the general public access to knowledge in books that had not been available to them previously, resulting in increased public knowledge and individual thought (“Elizabeth Eisenstein”, 2010). Whether the “Unacknowledged Revolution” is actually a revolution or not has been debated (Johns, 2002, Eisenstein, 2002). In ‘The Emergence of Print Culture in the West’ Eisenstein (1980) is the first to make a strong case for considering the impact of print as a cause of the rise of modern sciences. This essay will focus on the history of biology, specifically the study of human anatomy, and the roles of the printing press and print making press had on advances in the field during the Renaissance.

The book ‘Fathers of Biology’ (McRae, 1890) provides a detailed and interesting summary of the lives and works of Galen and Vesalius. Claudius Galenus (b.136 Pergamon) took anatomy to be the foundation of medical knowledge and conducted dissections on animals as it was taboo to dissect human bodies during his time. His writings serve as a record of the anatomical knowledge of that time period and were translated into Arabic for use as the basis of medical studies for over 1300 years. The Christian Church’s influence was so strong that any knowledge that contradicted Galen’s work was deemed heretical and punishable by death. Not until the 16th century was his authority called into question by Andreas Vesalius (b.1514 Brussels).

The founder of modern anatomy, Vesalius (b.1514 Brussels) was a physician and dedicated anatomist. He was proficient in many languages, he wrote his works in Latin and also learned Greek and Arabi for the purpose of reading the great biological works in their original languages. Vesalius completed human and comparative dissections and concluded that there were flaws in Galen’s anatomical works which were based on animal dissections. This put him in disagreement with Galen and all those who have believed in him for 1300 years. He wrote ‘De humani corporis fubrica (On the fabric of the human body)’ and was able to have some of the best artists of the time illustrate his work. Although McRae (1890) notes the detailed illustrations in Vesalius published work, he makes no mention of the use of new printmaking technologies or the printing press. This suggests the significance of printmaking and the printing press on scientific communication was not recognized at the end of the 19th century.

During the mid to late 15th century the reproduction of written materials shifted from the copyists desks to the printer’s workshop where Gutenberg’s invention, the printing press was being used to produce books. Prior to print manuscripts were copied out by hand, a time consuming and error prone task usually performed by monks (Tessman and Suarez, 2002). The printing press greatly increase the production of books and created a genre of technical literature in the vernacular language, accessible to those outside the university. However, use of the new mass medium was carried out mainly by pseudoscientists and quacks (Eisenstein, 1983). Eisenstein (1980) points out that the major written landmarks of early science, including De Revolutionibus, De Fabrica, and Principia, were all written in Latin by academically trained professional scientists. Therefore, there must be other factors besides the increase in production and availability of print to the public that account for the rise of modern science.

This Greek manuscript of Galen’s treatise on the pulse is interleaved with a Latin translation. (Manuscript; Venice, ca. 1550)

From the time of the ancient Greeks through the middle ages the works of Greek scientists lost clarity as accuracy of pictures was lost by the scribes. Over time the works of Vesalius lost their pictures and only the words were copied and translated (Eisenstein, 1983). Printmaking revolutionized scientific communication by making the timely duplication of intricate and precise diagrams, tables, graphs, charts, and maps possible. The use of accurate and repeatable pictures helped avoid confusion caused by the interpretation and translation of languages. During the 15th century the first images called woodcuts were done by using woodblocks for printing. Woodcuts were first used to combine typographic text with pictures in 1461 by the printer, Pfister in Austria (Mayor, A.H., 1971, cited in Tessmen, 2002). The influence of printing shifted scientific communication from ambiguous words towards precise pictorial representations (Eisenstsein, E., 1980).

Detail of frontisepiece of Vesalius' De humani corporis fabrica (1543), showing Vesalius and the corpse.

More recently the development of print technologies to the development of modern human anatomy has been recognized in academic writings (Ginn & Lorusso, 2008, Tessman, 2002). Some scholars believe there was little scientific progress in the field until the 15th century due to the lack of technology to make reproducible prints. (Ivins, 1992). The advancement of anatomy was dependent on the ability to make reproducible images. Printmaking allowed anatomical images to be distributed and alowed scientists to perform independent anatomical observations and compare results with others. Printing of books with images during the 15th to 17th centuries increased the accessibility of books, enabled self-education, and created a bank of previously acquired knowledge to build on (Tessman, 2002).

References:

“Elizabeth Eisenstein” (2010, July 4). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 20:20, November 7, 2010, from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Elizabeth_Eisenstein&oldid=371684323

Eisenstein, E. (2002). An Unacknowledged Revolution Revisited. American Historical Review, 107(1), 87. Retrieved from Academic Search Complete database.

Eisenstein, E.L. (1983). The printing revolution in early modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from http://books.google.ca/books?id=pyI7Lv__On8C&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false

Eisenstein, E. (1980). The Emergence of Print Culture in the West. Journal of Communication, 30(1), 99-106. Retrieved from ERIC database.

Ginn, S., & Lorusso, L. (2008). Brain, mind, and body: interactions with art in renaissance Italy. Journal Of The History Of The Neurosciences, 17(3), 295-313. Retrieved from MEDLINE with Full Text database.

Ivans, W.M. (1992). Prints and Visual Communication. Cambridge, Mass:MIT Press. Retrieved from http://www.archive.org/details/printsandvisualc009941mbp

Johns, A. (2002). How to Acknowledge a Revolution. American Historical Review, 107(1), 106. Retrieved from Academic Search Complete database.

McRae, C. (1890). Fathers of Biology. London: Percival & Co. Retrieved from Project Gutenberg.

Tessman, P., & Suarez, J. (2002). Influence of early printmaking on the development of neuroanatomy and neurology. Archives Of Neurology, 59(12), 1964-1969. Retrieved from MEDLINE with Full Text database.

Commentary #2 ~ Ryan Edgar

ETEC 540

Source: http://www.thismodernworld.org/arc/1990/90word-processor.gif

Commentary #2: How word processors have changed the writing process

There was a passage from our course notes that struck a chord with me. It is this passage that I have used as the focus for my second commentary. In paragraph 2 of the section titled The Calculator of the Humanist: Word Processing and the Reinvention of Writing (Module 4) it reads:

The text processor is transforming the way philosophy, poetry, literature, social science, history, and the classics are done as much as computerized calculation has transformed the physical sciences based on mathematics. The word processor is the calculator of the humanist . . . . It would seem that not only the speed of intellectual work is being affected, but the quality of the work itself . . . Language can be edited, stored, manipulated, and rearranged in ways that make typewriters obsolete. Extensive sources of knowledge can be accessed electronically and incorporated into the planning and drafting of ideas. This new text management system amplifies the craft of writing in novel ways. (Heim, 1987, pp. 1-2)

As I sat down to write this commentary I decided to stay cognizant of how I write. I asked myself, “do I write from beginning to end or do I tend to write in “chunks” and then organize those “chunks” into something that flows?” I never gave it much thought before in terms of how I write. What I have realized is I tend to first look for meaningful quotes or thoughts from my readings and/or research. After I have located these points, I write them down (ie: input them into my document). I organize them into some meaningful arrangement and build my paper out from there. I find it easier to find quotes and build out then it is to write a paper and try and find quotes that support my thoughts. Regardless of whether or not this is a good strategy for writing it is how I approach writing and more importantly it works for me. Keeping this in mind I realize that a word processor is vital in allowing me to easily manipulate my efforts.

In the past, one would have to enter a direct quote word by word. Although there are times that this is still done, generally there is so much available information on the World Web Wide that one can simply copy and paste the information from one source into another. It is like what Bolter (2001) stated when he wrote “They can erase a sentence with a single keystroke; they can select a paragraph, cut it from its current location, and insert it elsewhere, even into another document.” (p. 29) The word processor has allowed people to write almost as if they have “diarrhea of thought”.  Prior to the word processor, some writers experienced an overwhelming sense of fear as they struggled to get their thoughts down on paper before they would lose them. It is safe to say that one can type (on a keyboard) faster than one could write. Therefore, using a word processor allows one to keep up with their thoughts; one is able to get them down almost as fast as they enter the conscious thought (Bolter, 2001). “I only wish I could write with both hands,” noted Saint Teresa, “so as not to forget one thing while I am saying another” (Peers, 1972, vol. 2, p. 88, in Bolter, 2001, p. 33). Saint Teresa would have benefitted from a word processor – don’t you think?

Prior to the word processor, some writers experienced an overwhelming sense of fear as they struggled to get their thoughts down on paper before they would lose them. It is safe to say that one can type (on a keyboard) faster than one could write. Therefore, using a word processor allows one to keep up with their thoughts; one is able to get them down almost as fast as they enter the conscious thought (Bolter, 2001). “I only wish I could write with both hands,” noted Saint Teresa, “so as not to forget one thing while I am saying another” (Peers, 1972, vol. 2, p. 88, in Bolter, 2001, p. 33). Saint Teresa would have benefitted from a word processor – don’t you think?

The word processor has turned the process of writing into something that is “extremely malleable” (Bolter, p. 32). Prior to the word processor, writing was a progression of constant revisions. Now that is not to say that revisions no longer take place but as discussed earlier, making edits is a much easier task.  There is no longer the need for an entire re-write (unless you are completely changing the scope of what was written), only metaphorically speaking do we re-write our drafts. One could stipulate that the word processor has turned the writing process into play dough… allowing for a continual remolding of thoughts until it takes the form of what the writer is satisfied with.

There is no longer the need for an entire re-write (unless you are completely changing the scope of what was written), only metaphorically speaking do we re-write our drafts. One could stipulate that the word processor has turned the writing process into play dough… allowing for a continual remolding of thoughts until it takes the form of what the writer is satisfied with.

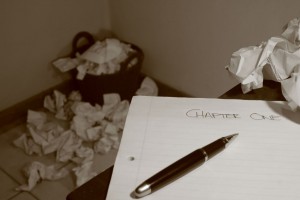

What is for sure is that the word processor has revolutionized the writing process. Getting one’s thoughts down on paper (albeit virtual paper), editing and even storage have all become more simplified with the advent of the word processor. However, what has not changed is the process of coming up with a focus or an idea that the writings will center around. The word processor can do a lot but the technology has yet to be perfected that will eliminate the human element in the writing process. What is written and the final “look” of how it is written is still in the hands of the individual. Having a word processor is similar to a craftsman having the right woodworking tools. Just because one has purchased the proper tools (ie: word processor) it doesn’t mean that one will be able to build a house (ie: write properly). The skills required to write competently are independent to having a word processor. However, having the right tools sure makes the process easier!

Bolter, J.D. (2001). Writing Space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Teresa Dobson and John Willinsky’s “Digital Literacy” article offers a thorough historical overview of the realities and challenges of the written word in a digital landscape, but falls short in fully analysing some of the important changes in this evolving environment. The very fact that these ideas are presented as a static PDF chapter of a more traditional book unfortunately frames the authors as perhaps not having an incredibly high level of engagement with this changing landscape. This is a field that is changing so rapidly that it is almost impossible to accurately document, but this work does serve as a good starting point in further discussion.

In discussing the evolution of digital literacy and various technologies, the authors make note of several affordances that these new mediums allow. One such example, the ability to easily revise and edit a text, should be central to any discussion of digital literacies, as this new ability has transformed the written process. Authors are now able to write more impulsively, and do not need to give careful consideration to each word before it is ‘written’. Dobson and Willinsky see this as largely a net benefit, and most would agree, however some question should be made of what this means for the creative process. It is entirely possible that many authors now create works more hastily, and without giving as great a thought to overall progression of a work. The ability to easily cut and paste ideas means that a work may not necessarily represent a progression of ideas as they naturally occurred, but rather may be a reflection of several rounds of editing and revision.

Dobson and Willinsky do make note of this change in the writing process somewhat when they discuss a loss of immediacy in written work, but they also acknowledge that it is not entirely clear how word processing as changed the way we write. It is unfortunate that the authors do not delve into greater detail in this area, as it is likely that a great many changes have occurred to the writing process as a result of the widespread adoption of word processing. The reality that touch typing is now an assumed skill in many implies that word processing has greatly expanded the pool of potential authors (whether of creative or of more practical works), and the very idea of using a standardized roman alphabet keyboard has likely also meant a great deal of change on the writing landscape, and indeed on language in general.

Dobson and Willinsky’s analysis excels in its discussion of the notion of hypermedia, and the authors do an excellent job of summarizing the historical growth of this concept. They make particular note of the non-linear nature of this type of text, which is key to understanding how it has changed the written word. Unfortunately though, the rapidly evolving landscape of digital technologies has meant that much of the work cited by Dobson and Willinsky is now dated to the point of possible irrelevancy, as it does not encapsulate the current media-rich and highly social environment where a great deal of writing now occurs. The authors allude to this in their discussion of literary hypermedia, as they note that this is area represents a minority, but rapidly changing and evolving segment of digital text.

The authors note, quite rightly, that the words that we read on a screen are created as binary strings of code that can be easily created, modified, and viewed digitally. This is rather irrelevant though, as the digital written word that is now common to our experience is never intended to be viewed in this raw coded form, and this digital transformation is now so completely automated that really no knowledge of this code is necessary of either the writer or reader of digital words. Making note of this point is similar to implying that traditional type-written texts should be considered as constructs of this mechanical process of inked keys pounding on paper. While this is the physical reality of these creations, it does not hold relevant or necessary to consider when examining a written work.

Dobson and Willinsky’s article serves as a good summary of the historical progression of digital literacies, but it should be viewed only through that lens. To discuss the realities and implications of today’s digital landscape requires one to keep up with an online environment that appears to change almost overnight, and so it is likely that we will only have a full understanding of this reality in hindsight. The irony that these authors chose to present their ideas in a traditional and static format that is reminiscent of a pre-digital world should not be lost on the reader. Discussing statistics from 2003 may have some use in helping us to understand where we are coming from, but in a digital landscape that changes with each tap of an iPad, it is becoming increasingly difficult to effectively assess our current situation.

Here is a link to our WordPress site. Please come and have a look to learn all about the invention of the telegraph.

Alison Baillie and Leslie Dawes

http://telegraph540.wordpress.com/

Commentary #2

Commentary #2

Chapter 2 in Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print

In the opening chapters of Jay David Bolter’s Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print, the idea of remediation begins to take hold. Bolter(2001), in Chapter Two, discusses writing as technology, taking up where Ong (1982) leaves off in his text, Literacy and Orality, and outlines the remediation of print from orality through to the computer.

The idea of writing as material or economic is brought forth in Chapter Two. In order to show that the pen and paper are also technology Bolter writes, “the production of today’s pens and paper also require a sophisticated manufacturing process.” (Bolter, 2001, p.17). Here, Bolter writes about print as a material and economy, and, in turn, creating the question of using writing to make money. Writing, according to Bolter (2001) is the remediation of orality. Speech in the western world is free and if writing is its remediation, it would seem that writing should be free as well; however, Bolter points out, that writing is far from orality as there is an economy surrounding writing. Bolter does acknowledge that remediated things are different from the original product, but writing seems to hold a very different purpose than orality. If we adhere to Marshal McLuhan’s (1967) assertions that the medium is the message, than it would reason that writing, even with a pen, is an economic activity, unlike orality. This is true with all print technologies, from the printing press to the computer. Therefore, writing is not merely communication, it is also closely tied with making money- a function of economy.

This begs the question of who is driving these changes in print, especially today, when every year there is new word processing software? Does the natural evolution of print create these changes; is it deterministic? Or would it be a company like Microsoft who sees that writing is not merely communication, it is money; is it a fundamental way of our culture to perpetuate our consumer society? How do the powers that drive the change effect the way we write? These questions are only to be answered by time.

Print is remediated by orality according to Bolter, who writes “they speak, as they write, in a variety of styles and levels, and they often structure their speech as they do their writing in talking in sentences and even paragraphs” (Bolter, 2001, p. 16). Ong wrote that oral societies spoke formulaically in order to preserve memory. This formula was obviously carried over from speech to writing as Ong demonstrates with both Genesis in the Bible and Homer’s poems (Ong, 1892, Ch. 3). This formula would have carried a speech pattern, like all other forms of oral speech, just as writing carries a pattern. Therefore, grammar is remediated from orality to print. It stands to reason that if oral people spoke using grammar structures without ever writing them down, grammar teachers could benefit from the study of orality and how speech formulas were transmitted from one individual to another or to one culture to another. As Bolter and Ong demonstrate, people are capable of creating complex formulaic speech without writing.

Bolter’s view of remediation of print or many other aspects of communication creates a view that nothing has changed to the extent people might think it has. If writing is the remediation of orality and print is the remediation of writing and the word processor is the remediation of print, than somewhere there have been constraints. In the age of technology, it is evident that people often get excited about the possibilities of the ideas of new technologies, but, as Bolter points out, we are just changing the old way in a minute manner. Many aspects of the necessity of remediation are evident, such as ease of use, but it seems our preconceptions about the previous technology are constraining what we can do with that technology. If the computer were invented just as writing was, would our computer screen really just look like a piece of paper? Could it be that a piece of paper has created a version of word that is constrained because that is what we know, so we use it? There is a movie trailer for “The God’s Must be Crazy” (2009) where a tribe in Africa, who do not have much connection with the outside world, get a hold of an empty bottle of Coca-Cola and use it as a pestle, a way to crack a coconut, and a tool to dye cloth; many ways in which most people would not think to use a Coke bottle. These people did not have a preconceived notion of what the bottle was used for and found multiple uses for it.

Bolter’s observations of remediation also brings about ideas that we know what something is used for and therefore are less able to think “outside the box.” We could find many more uses for technology if it were not remediated from something familiar.

“One medium sets out to remediate another, it does so by claiming to do a better job” (Bolter, 2001, p. 26). Bolter’s conclusion for this chapter takes on a new message when you look at through the eyes of economy and the constrictions of remediation. The computer does do a better job than a typewriter, but it also costs more money and has the ability to change the economic message. The new medium might do a better job but is still constrained by the old medium and has the potential to do a better job. Remediation creates new messages that are still constrained by the past.

References

Bolter, Jay David. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print [2nd edition]. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. ISBN: 0-8058-2919-9

McLuhan, M. (1967). The medium is the message. NEA Journal, 56(7), 24-27.

Ong, Walter. (1982.) Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Methuen.

20th Century Fox (2009, October 4) The God’s Must be Crazy. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GorHLQ-jLRQ

The Picture was retrieved from here