The Natives are Restless

By Laura Bonnor and Soraya Rajan

In “Digital Natives/Digital Immigrants”, Prensky (2001) outlines the challenges for today’s teachers when confronted by the technological natives in their classrooms. In “Growing up Digital,” Tapscott (1997) suggests that the “children are the authorities,” and that teachers have to get used to that. Tapscott goes on to explain that from age 8 to 18 is the adolescent brain is creating and developing the neurological pathways that will serve them in the future. So many of today’s youth are engaged in multi-tasking with technological tools, their brains are developing differently from the brains of the previous generation. This is, according to Tapscott, leading to a ‘generation lap’. These students are able to challenge their teachers and parents with their linking, navigating pathways and networks, seeking new experiences through the ever emerging spaces on the Internet. The conventions, organization and structure of hypertext is challenging our perceptions, beliefs and expectations and even our cognitive abilities. Tapscott (1997) discusses adolescents as having a better active working memory and “switching” ability, allowing them a greater ability to multi- task. Both hypertext supporters, (Bolter, 2010) and Tapscott (1997) see it as an interactive, associative, layered and a learner centric, critical thinking environment populated by users that is spread out in all places of the world but is yet connected globally. All of this seems to suggest that there is very little room for traditional teaching practice. If this is true, what is the role of the educator in today’s schools? Are educators prepared to act as facilitators? Can the students teach themselves or rely on the technology to teach them what they need to know? Is there a role for the elders, who may be “heavily accented, unintelligible foreigners” (Prensky, 2001) in today’s technological world? It is possible that the educator with the accent has critical literary skills to analyse and evaluate hypertext materials that are not conducive to constructing knowledge and critical thinking ?(Horning, 2002). Does everyone have an accent in the technological world with some accents being left unheard? Survival will depend on adaptation through reading and writing spaces and with the assistance of a well informed facilitator.

Both Prensky and Tapscott claim that “our children have changed dramatically” (Prensky, 2001) (Tapscott, 2009) While current brain research is changing what we understand about the brain and we are aware that the adolescent brain is in a critical phase of development, do we know that this change is happening faster than in previous generations? Greenfield (2010) thinks so, but since our MRI technology has only been used to analyse brain activity for the past ten years, it could also be true that major societal adjustments such as literacy of the adoption of the automobile have always lead significant changes in brain-structure. Even if we accept that this change is happening and is different from changes that previous generations have gone through, we should at least ask ourselves if and how we, as educators can support this change? According to Bolter, hypertext is constructive as reading hypertext is interactive with the reader conscious of the text moving on a virtual journey through the visual and conceptual spaces created by or with the author (Bolter, 2001). SInce reading and writing hypertext moves one beyond print text into globally connected spaces beyond the reach of those readers viewing the print text there is a major change in the use of the brain. Perhaps this can account for the changes noticed by scientists in viewing MRI’s of the brain. As educators, with brains less suited to the environment, we may find it challenging to compete with electronic learning spaces. Items that we would use in our more ‘traditional’ classroom, that we may even consider diverse, such as newspaper and radio are being replaced at a rapid pace by sources found on the World Wide Web. Don Tapscott explains that in many ways, today’s youth are moulding the culture that is expanding, driving and defining Bolter’s remediation of text to hypertext and hypermedia. Tapscott and Prensky both suggest that it is educators role to ensure that this responsibility does lie solely with the adolescent but that educators must seek out ways to share that responsibility.

Both Prensky and Tapscott feel the current education system is not meeting the needs of students. “Today’s students are not the people our system was designed to teach” (Prensky 2001) I would have to suggest that this current grade-age based system was never designed to teach children. As Goodlad (1963) and many others have chronicled, our current public education was designed on a factory model to produce a more educated and useful workforce. It is possible that technology and its promise of individualized learning sheds a harsher light on the inadequacies of this system. It seems overly harsh to create such great divide between the digital natives and the digital immigrants laying the blame for an outdated model on a rift between adolescents and educators. The challenge of adults communicating effectively with youth has always existed. The tone of the Prensky and Tapscott suggests that the leading role should be played by the youth in the education system. According to Taspcott, today’s students have the tools to question, challenge and disagree; they are becoming a generation of critical thinkers that love to argue and debate. Does hypertext and hypermedia really provide tools that are interactive and encourage critical thinking as Tapscott suggests? Does this new ‘student centered’ ideology support the goals of global society? Does it create self- directed students engaged in constructing knowledge that they find to be true? As educators, perhaps this is our place to guide students and teach them to look at many sources critically to find truth even on the NET.

Although, ultimately Tapscott and Prensky state that educators need to engage the learners and approach the problem in a balanced fashion, neither expresses any need for caution with regard to adopting technology. Tapscott cites studies that were conducted by major corporations and acknowledges the role that major corporations play in the adoption of technology but does not seem to observe that these companies and technologies may not be benign. Plensky cites that youth are spending endless hours playing video games and being digitally absorbed. While this is true for many youth, we should question if this is a positive outlook. Plensky suggests that the programs will teach the students (Prensky, 2001) He suggests that we aught to put ourselves in the hands of whichever programmer or corporation that has created the product without necessarily any critical thought or guidance. Further research by Horning (2001) in her analysis between hypertext and critical literacy have showed that students often click from page to page when conducting research; if they do not see the information that they are looking for on the first page few investigate further. Perhaps today’s youth are good at video games, surfing, skimming but what about their attention span, and their ability to select, evaluate and interpret information in a critical manner? (Horning, 2002) Can we really agree with Tapscott and Prensky that the programs and the net are positively benefiting our youth? As Neil Postman (1992) reminds us, there are positive and negative aspects to every technological change and to embrace new technology without critically thinking about all the implications is foolhardy. Students benefit from being exposed to variety and if they don’t know what a “dial” is, perhaps they should learn that the world at this second is not all there is or was. We stand on the shoulders of our ancestors.

Both articles stereo-type both the older and younger generations. It is not true that all students are digital natives and neither are all adults digital immigrants. Brown and Czerniewicz (2010) determined that technical skill was more and attribute of the “digital elite” and a product of “access and opportunity” in their study of students in South Africa. Throughout the world there are varying degrees of digital acceptance and adoption. Furthermore, these terms carry excessive baggage suggesting that one actually belongs and the other belongs somewhere else or that one is less valuable to society than the other. Brown and Czerniewicz, refer to this polarization as “digital apartheid”. Plensky makes assumptions about the level of networking that he attributes to most if not all students and certainly about the level of skill, or lack of same, of most if not all educators. There is a wide skill range amongst both groups. Prensky’s model of natives vs. immigrants only further to widen the generation gap.

The sweeping generalizations such as “digital immigrants think learning (shouldn’t) be fun” (Prensky, 2001) and that students “won’t take it” (Prensky, 2001) are generally unfounded and anecdotal. Both of these statements cater to a narcissistic cultural that it might be better to control, rather than encourage. Greenfield (2010) suggests that this attachment to video games and instant gratification be considered as similar to drug addiction and if so is it not essential that we act to protect students? It seems that we should not be so quick to denigrate certain areas of learning such as reading to a “legacy” (Prensky, 2001) skill and run headlong into the future with new, untried skills? In many ways, both Plensky and Tapscott seem too eager to throw the baby out with the bath-water. While it is true that many educators would benefit from developing skills with new technology, it is equally true that many students would benefit from continued development and reflective learning opportunities using old technologies. Brown and Czerniewicz (2010) suggest that trying to achieve a “digital democracy” might be more appropriate. The tool that they suggest is the most useful is the ubiquitous cell -phone that is used by old and young, rich and poor alike in nations across the world.

Prensky and Tapscott are enthusiastic about the potential of newer technologies to reach students and the students ability to manage the pace of change. However, they suggest a complete shift in the societal structure that gives the adolescent never before imagined control over their learning. The knowledge transfer changes from elder to youth and presumably a power would shift along with that. Given Giedd’s work on the adolescent brain and Greenfield’s concern about the effects of technology, this may be more responsibility than the students are able to manage. Tapscott himself admits that the studies for his book were funded by large corporations. It seems naive to assume that the large corporations only care about the good of society. While technology offers great potential for learning and educating in the decades to come, such unbridled enthusiasm, heralded at the cost of tradition and wisdom that pits one group in society above another, needs to be taken with a certain amount of caution.

References

Brown, C. and Czerniewicz, L. (2010) Debunking the ‘digital native’: beyond digital apartheid, towards digital democracy. Article first published online: 15 SEP 2010. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning Volume 26, Issue 5, pages 357–369, October 2010

Giedd,Jay. (2002) Inside the teenage Brain. Frontline, PBS Special.(original airdate January 31, 2002) Goodlad, John I. (1963). The Nongraded Elementary School. New York. Harcourt, Brace & World Inc.

Greenfield, Susan. (Nov. 14, 2010) Modern Technology is changing the way our brains work, says neuroscientist. Mail Online: Daily Mail Associated Newspapers.

Horning, A (2002) Reading the World Wide Web: Critical literacy for the new century,

The Reading Matrix Volume 2, Number 2, June, 2002

Postman, N. (1992). Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. New York: Vintage Books

Prensky, Marc (2001) . Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. From On the Horizon (MCB University Press, Vol. 9 No. 5, October 2001)

Tapscott, Don, “Growing Up Digital” Interview with Allan Gregg. (April 2009)

Tapscott, D. (1997) Growing up digital: the rise of the net generation. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Power Shifts Reflected Through Changing Literacies

“The issue—given that representation, especially in the linguistic modes of speech and writing, is so closely bound up with social and ethical values—cannot be debated at the level of representation alone. It does, always, have to be seen in the wider framework of economic, political, social, cultural and technological changes. This is so because on the one hand representation is used as a metaphor for social, cultural, and ethical issues, and because on the other hand representational changes do not happen in isolation. The technologies of representation and those of communication and/or dissemination are everywhere bound up with the larger, wider changes in the (global) economy, in social and political changes, and in accompanying ethnic and cultural changes.” (Kress, 2005, p. 6)

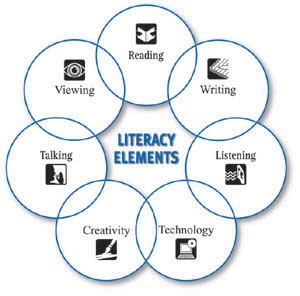

In an examination of gains and losses in new literacies and ways of knowing (Kress, 2005), I cannot help but wonder if our shift from traditional text-based literacy to multiliteracies – spurred in part by the integration and even dominance of the visual image into common information resources – will result in a much more significant shift, that being a power shift from note-worthy authors to the empowerment of every and any individual seizing his or her opportunity to have voice ¹. So situating the need for multiliteracies, then, demands evaluation of social and ethical values and the greater political, economic and cultural changes that such a power shift may both invite and reflect.

Cautious to avoid being apocalyptic with regards to the possible extreme our shift towards the individual could reach, reading Kress (2005) expounds – for me – that the literary shifts experienced over the last 50 years will be reflected in reassignment of power from author to reader, from leaders to the individualized everyman. This power shift, encouraged under the worthy guise of goals for children then adolescents to become increasingly independent, may have unintended repercussions.

Kress (2005) details a linguistic shift describing modes of message delivery: where the book has readers, the webpage has visitors. Websites are being designed to be visited, rather than written to be read. With only the possibility of websites’ linguistic text being read, this may not only predetermine the change of literacy and reading but also a change in power structures with regards to what constitutes authority. We are designing pages not to be read but to merely offer information which the visitor may or may not choose to attend to in a way we would traditionally call reading. Presuming visitors will attend only to the most immediately attainable information, we design pages so as to sculpt a shattering of attention via multimedia, reinforcing scanning behavior, a perceptual literacy rather than attentive literacy. This invites visitors, learners, to resort not to the traditional authority of the author, but to construct knowledge of their own. This is in many respects laudable and desirable and rests alongside sound constructivist pedagogy, but ultimately, when or how do we enforce the actuality of authority beyond the individual? And do we need to? While literacy itself is requiring re-evaluation (New London Group, 1996; Dobson and Willinsky, 2009) in today’s cyber-presentation of information, as readers/visitors change their approach to the page, a deeper re-evaluation of how this reflects power structures may also be prudent.

Reflecting the ongoing trend towards the individual associated with the rise of the novel among other historical socio-cultural factors in the 1800s, the shift from competence to critique in the late 1960s to early 1970s (Kress, 2005) also shifted the emphasis from ability (positive) to inability (negative), asking the questions, “where does this fall short?” and, “how does this measure up?” The confrontation found in critique of an author’s writing is again a power issue, but “the project of critique seems somewhat beside the point” (Kress, 2005, p. 17). We have already progressed to the next shift Kress (2005) details: from critique as the reader acting upon the author’s work to design as the reader distancing that much further from the author’s work, using it as nothing more than catalyst for one’s own thinking. With this, the power shifts further toward the individual and the social system is decidedly in crisis (Kress, 2005, p. 17).

There is constructive power involved in knowledge-building within society, but in the way detailed thus far it is not societal; it is individual. And it is increasingly moving away from dependence and interdependence towards a greater independence, a greater individualism in linguistic expression. With respect to the less powerful critique (compared to design), Kress (2005) reflects that

It challenges the existing configurations of power and expects that in exposing inequities more equitable social arrangements could be developed. In terms of representation that would amount—at that time when the focus was clearly linguistic—to lessening the effects of power and its realization in linguistic form. (2005, p. 17)

As readers and critics become designers – as opposed to becoming writers, a more difficult transition – incorporating the image as much or more than the word into their designs, the linguistic form becomes less powerful. Its message is conveyed by its multimedia accompaniments; when the words are not readily comprehensible, the remaining visual and/or audio design elements will ease translation. In so doing, the words are side-stepped. They need not be understood in and of themselves. This may lead to greater social equity, but – for better and worse – it may be at the expense of traditional literacy. With design, power is shifting from the linguistic to multimedia, and from the author to the reader. (The shift is not complete, nor may it be for some time – published work such as a journal article carries credentials readers still do not possess and which continues to demand the linguistic form for full explication. Case in point is my consultation with and reference to Kress as a notable author with published work in a reputable journal. My work certainly does not stand alone as authority.)

The trend toward the digital is not likely to be ebbed any time soon. We are not likely to change web design to preserve or enforce traditional text-based literacy, nor should we. With concerns of what this shift means socioculturally, “Reading has to be rethought given that the commonsense of what reading is was developed in the era of the unquestioned dominance of writing, in constellation with the unquestioned dominance of the medium of the book” (Kress, 2005, p. 17). Multimedia feels more natural, intuitive, but with the shift, we do move against a culture that has been of force for 500 years. In doing so, we challenge power structures. Our linguistic freedoms in reading, expression and the expansion of literacy to multiliteracies need to be connected to their effects and correlations in the larger societal picture.

Coming back to this now & subsequent to Jeff’s feedback, I see it is reminiscent this is of Roland Barthes’ “The Death of the Author” (1977). This was entirely unintentional, but now noted, I think it is worth connecting so here it is. In this, Barthes also attributes a certain power to the reader (though it is equally important that I note he undermines the reader being anymore than “simply that someone who holds together in a single field all the traces by which the written text is constituted”):

“Thus is revealed the total existence of writing: a text is made of

multiple writings, drawn from many cultures and entering into mutual relations of

dialogue, parody, contestation, but there is one place where this multiplicity is

focused and that place is the reader, not, as was hitherto said, the author. The reader is

the space on which all the quotations that make up a writing are inscribed without any

of them being lost; a text’s unity lies not in its origin but in its destination.”

References

Dobson, T. and Willinsky, J. (2009). Digital literacy (draft). The Cambridge Handbook on Literacy. Retrieved online at http://pkp.sfu.ca/files/Digital%20Literacy.pdf

Kress, G. (2005). Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge, and learning. Computers and Composition, 22 (1). Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2004.12.004

doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2004.12.004

The New London Group. (1996). A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies:Designing Social Futures. Harvard Educational Review 66(1). Retrieved online at http://newlearningonline.com/~newlearn/wp-content/uploads/2009/03/multiliteracies_her_vol_66_1996.pdf