In a world where nothing is written and words are not thought of in separate entities and people only speak, we, the typographical/chirographical people, cannot judge.

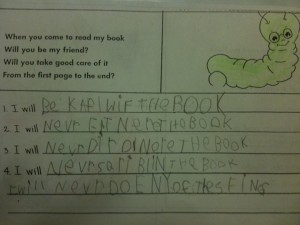

Walter J. Ong’s book Orality and Literacy focuses the reader’s attention on those people who have lived or do live in an oral culture and what it would be like to live in an oral culture/society. His sentence “Try to imagine a culture where no one has ever ‘looked up’ anything” attempts to put the reader in the shoes of a person from an oral culture. Ong specifically explains that oral cultures use mnemonic devices and formulas to remember important events and describes that the recitation of a story is rarely the exact same with each telling. He found that the story was not always accurate, but was told to the audience according to the way the teller wanted to tell it – literally becoming hisstory. If a bard told a story according to the audience or according to the way he/she thought it should go, the history turned into his/her story.

Our western typographic/chirographic culture does not see the tendency to change a story as a legitimate way of remembering, but complete accuracy might not have been an important aspect of an oral culture. It could be that, in our literate minds, we construct this idea that things must be presented exactly how they occurred when, in fact, these oral cultures had no need for this. When Ong writes about imagining oral culture, he alludes to the fact that our brains may not understand their practices because we have been so immersed in a culture of writing and scribing.

This immersion of a writing culture is problematic for Ong as he is writing from the perspective of a person coming from an oral culture and also is writing about oral cultures. It may be impossible for anyone who has lived in a writing society to fully understand and accurately convey what an oral culture was like. This also leads to difficultly in accurately describing an oral culture as it appears that those members were not concerned with accuracy themselves due to the ever changing nature of the story. The only way Ong could truly discover what an oral culture was like would be to interview a person in an oral culture and record the interview. This method would be problematic as the person from the oral culture might not be able to reveal the differences between orality and typography/ chirography, as they have no knowledge of a literate culture.

This brings us to the study Luria did of illiterate people (pg. 50). While these people might know some aspects of oral culture and literate culture, they also would not be true oral cultures resulting in a catch -22. Ong’s inclusion of these studies is enlightening, but problematic, as these people, to some degree, have been exposed to writing and may be completely different from the oral cultures before cuneiform. Also, Ong includes resources from the Bible and Plato, but these resources are all written – not spoken therefore his resources should be called into question. The only evidence that survives of truly oral people are all written down. How much of the semi- admissible information that Ong presents is due to the difficulty of collecting authentic resources? Again, this leads us to the question the importance that we ‘correctly’ reveal these people as they might not even worry about themselves?

Ong’s chapter on the psychodynamics of orality does have some resources that should be questioned, but in the same token, they provide interesting insight into a culture we have little knowledge about because it is not written down. While I read Ong’s book, I wondered two things: one is about the illiterate people in Canada and USA today and the second is how we can use this information in a classroom.

If illiterate cultures were studied by Luria and written about by Ong, what could their research mean to the study of illiterate people in Canada and USA today? Would they have similar qualities to the illiterate people that Luria studied? It seems as though technologies will eventually be incorporated by everyone, like writing, but to what extent are the illiterate people of today still trying to incorporate the technology of writing into their everyday lives? Will this happen with the computer? Will the computer last that long and will there still be illiterate computer users thousands of years from now? Does it take that long for a new technology to engulf the entire population? Will it ever?

I think that the illiteracy in the sense of merely reading and writing will always be there because of many different disorders, but as history has shown us, the trend is that the illiteracy rate will decline. If the computer lasts as a technology as long as writing has, then I believe computers will go the same way as writing. The rate of integrating learning the new language of the computer might be faster because of the computer. It connects to the world in a matter of seconds so this new technology could create a rate of learning that far exceeds that of writing.

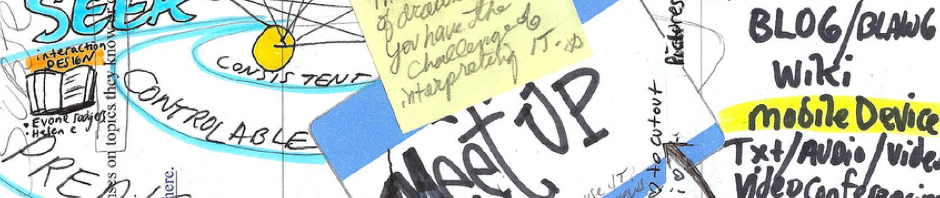

While reading the chapter “Some Psychodynamics of Orality” I began to think about ways to include forms of memorization, utilized by oral cultures, into the classroom. As I teach students how to speak English, I found learning with mnemonic devices, formulas, and other strategies mentioned in the book might be helpful. I performed a little bit of research on my own (admittedly very small and not very scientific) asking my friends how they remembered information. More often than not, those who did well in school used many of the devices that the oral cultures used. So, as this world comes to a bottleneck of information overload, I wonder if we can use the information of our oral ancestors to learn the most important things – the things that we need to know faster than a computer can load?

Technopoly: will it survive?

People working in educational technology are inundated with latest tools all proclaiming to act as major disruptive forces in traditional education. It is easy to get swept up in the excitement of innovation and become marketers of various technology applications in our school settings. It is also easy to introduce and promote these tools as they become available without much thought to the long-term consequences. Neil Postman, in his article Technopoly: the Surrender of Culture to Technology articulates the “dangerous and disturbing” view of technology that should be addressed today. (Postman, n.d.)

Bill Gates often says that people tend to overestimate technology in the short term and underestimate it in the long term (Kirkpatrick, 2010). In my undergraduate classes in the 90s I learned of the coming impact of the Internet that would change education forever. That decade passed with little change. The educational impact of technology that was prophesized by some of my professors simply did not revolutionize the way we learn. Search technology such as Yahoo and later Google allowed us greater depth of research but there was no pressing reason to change teaching methodology.

It was during this time that Neil Postman was proposing his pessimistic view of technological capabilities. In his article, Tehnopoly: The surrender of culture to technology, Postman alerts us to the negative impact technology can have. He also proposes that humans have little control in this direction, “Once a technology is admitted, it plays out its hand; it does what it is designed to do” (p.7). This is what Daniel Chandler (2002) refers to as “technological determinism” (Introduction section, para.2). From this perspective, we have no control in the development in technology. In fact, Postman suggests that the best we can do is be aware of it: “when we admit a new technology to the culture, we must do so with our eyes wide open” (p.7).

Contrary to this view, I believe those in the educational technology have the power to go much further than the awareness level. When technology is admitted, we should be judicious in its use and apply it in a way driven from instructional design that will captivate students and promote student learning to broad audiences. That is, the usefulness of educational technology should be evaluated in terms of its alignment to course outcomes and assessment rather than its function outside the context of pedagogy.

The other important issue that Postman raises concerns knowledge monopolies. It is true that in the past technology was often controlled and exploited by the few. In the past century, television, film, and telephone were industries completely controlled by a handful or collaborating competitors. The result was, and still is, an overpriced system with poor quality. This system fit well with modern marketing that supported a narrow spectrum of content and benefitted the producers far more than the consumers.

The development of web applications in the past few years, however, moves in a direction that may actually break up this knowledge monopoly. Schools such as MIT, which Postman says have been a part of the knowledge monopoly created by the invention of print, are now offering Open Courseware. The traditional consumers of information are now also producing content in wikis, blogs, and video. In this development stage, there is a democratizing of information where the powerless are empowered to collaborate in new ways; but how effectively and for how long? Popular writer Malcolm Gladwell argues that relationships built on social media platforms are weak and unable to create real social change such as the change that took place in the 60s (Gladwell, 2010). Do we as educators play a role in helping students to strengthen these relationships to enable positive social change? How long will these tools remain democratic? Can we trust Google to continue to “not be evil” by keeping content open, or will they become another example of what Postman describes, an elite company accumulating power to serve itself.

When we consider how social media has developed in recent years, we can see that Postman got a few things wrong. For example, the computer did, and will not, kill “communal speech” in the classroom; it in fact enables it though various web applications. Postman believes that technology changes fundamental concepts such as “knowing” and “truth”. For now, as we witness applications such as Twitter challenge political authority as it did last year in Iran, it would seem it is giving these concepts back to people. Moving forward, we may benefit from asking the balanced questions Postman raises in order to prevent the knowledge monopolies from appearing again in new forms.

References

Chandler, D. (2002). Technological or media determinism. Retrieved from http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/tecdet/tdet01.html

Gladwell, M. (2010). Small change: Why the revolution will not be tweeted. Retrieved from http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2010/10/04/101004fa_fact_gladwell

Kirkpatrick, M. (2010). Google TV will “change the way people live their lives”. Retrieved from http://www.readwriteweb.com/archives/google_tv_will_change_the_way_people_live_their_li.php

Postman, N. (n.d.). Technology: The surrender of culture to technology. New York, NY: Vintage Books.