An overview of a Remediation: From Scroll to Codex

Introduction:

Writing as a mode or method of human communication, has been in existence for a very long time and has been continuously evolving, progressing, regressing, moving forward, and changing (Botero et al 2000). These processes of change, these transitions or remediations of ways of writing, reading and of knowing are shaped by and acted upon complex socio/political and historical/cultural forces that continue to inform our ways of communicating today, at the cusp of the twenty first century (Bolter 2001).

A brief overview of the trajectory of a specific remediation, that of the transition from the primacy of the use of the Scroll as a way of storing and communicating written text and knowledge into that of the Codex will be the focus of the discussion to follow. Remediation here will specifically refer to the movement from one media or mode of written communication to another as described in Jay Bolter’s work about writing in the context of the advent of computers (Bolter, 2001). It should be noted that the outline of the cultural and political forces at play is limited here not only to a specific western and Eurocentric context but also to a specific chronological period or range, with a primary focus on the late Roman period extending to about the third century AD. This particular remediation traces a fascinating and complex path, weaving a trajectory through great cultural and historical shifts that occurred over a period of several hundred years.

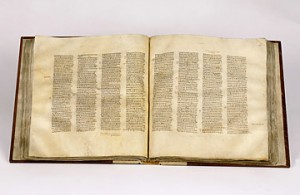

Scroll to Codex: One of the First Bibles [1]

Scroll to Codex: One of the First Bibles [1]

Writing in its many forms has always communicated the literal content of the text, however, the information contained within the text and the way and the format in which it is presented communicates much more (Edney, 1992). The Scroll and the Codex “speak” of or describe the extant power relations of the historical moment, and in many ways also of the specific culture from which it emerged. Writing delineates and reflects specific epistemological systems and communicates what a specific culture considered important enough to be considered Knowledge (Mokyr, 2002).

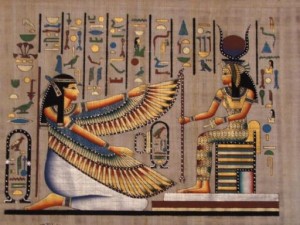

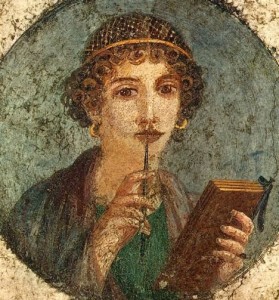

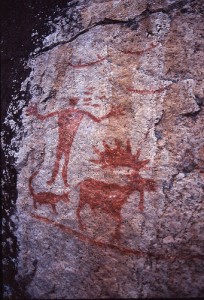

Moreover, the act and process of writing is not a neutral one; nor are compilations of writing, whether contained in Scroll or books, neutral artifacts. Where ever writing appears and in whatever technological form it manifests, it bears the very specific imprint of the cultural, political and economic influences that shaped and created it (Bolton ibid). This holds true for all forms of writing over the vast expanses of recorded history as they are all grounded in the specifics of their unique cultural and historical milieu. From the ancient hieroglyphics of Egyptian dynasties, to the letters on the papyrus Scrolls of the ancient Greeks or the illuminated manuscripts of medieval Europe, from the printed pages of industrial era texts to the digital traces of keystrokes in the email communications of modern societies; all reveal and reflect the culture and the power relations within that specific historical moment or epoch.

The act of Writing: framed by culture and by history [2]

This discussion will demonstrate that the remediation of writing on the Scroll as it reconfigured and resituated itself into the technology of the Codex was enabled by a unique set of cultural forces, and was framed by the socio-economic and political power relations of a specific historical context.

A brief introduction to the terminology used here and the historical and cultural contextual backdrop to this transition will begin the discussion, and an examination of the changes that occurred to transform the Scroll into the Codex will follow.

Terminology:

Remediation as used by Bolter is a process, it describes the transition from one media or mode to another, it is dynamic [not static] it has the potential to be and frequently is, evolutionary, but not necessarily logically progressive. It is a series of changes, but they are not simple or linear trajectories of change. The process of remediation may involve simultaneous progression and digression, and tangential leaps forward followed by regressive movements away from positive innovation. All of these changes involve a myriad of forces and or characteristics having nothing inherently to do with the actual media or medium itself (Bolton ibid). To sum up, the process of remediation of modes of communication is as complex as the historical and cultural forces that shaped those changes.

An example of Graffiti: late twentieth century writing [3]

An example of Graffiti: late twentieth century writing [3]

A similar qualification must be placed upon the meaning of Codex. Although it evolved over time to have a specific meaning within legal contexts, in our examination here the term Codex will denote leaves of wood, papyrus, and more frequently, to parchment, bound together into the form of a modern volume, or what is commonly referred to as a book.

When referring to the term Scroll we are going to define it for the purpose of our discussion here as very simply a roll of paper [originally papyrus] or of parchment, usually, having writing on it.

The Process of the Remediation of Writing:

The remediation of writing is complicated because the process is not only driven by functional or rational requirements, that is, it is not just a series of what could be evolutionary or progressive innovations or improvements to a particular medium [employed as communication device] over time. Nor according to Bolton, is there a clear division or cut off between the use of one medium to the other.

Writing is Knowledge & Knowledge is Power:

Throughout history the use, access to and control of modes of writing, has been recognized by all cultures, as was noted above, not just for its inherent importance as a way of communicating, but also as an effective way of demonstrating and communicating power. Therefore, what is conveyed within a specific scroll or codex [or book] has always been something more than just its literal, surface or even just its cultural meanings. Writing and the information a civilization formulates into knowledge, as it manifests and is contained in scrolls and in books, issues out of a complex mixture of cultural and historical forces that frame and represent specific ways of perceiving and of interacting with the world (Lunsford 2006). These cultural and historical forces fuse with ways of knowing [systems of knowledge and knowledge acquisition or learning] that are specific to each unique context. All cultures in the western context from the very earliest of times, seem to have shared a recognition that being able to control the distribution, the storage and the access to knowledge [including what is left in and what is excluded from that corpus] that is incorporated within written texts, is both central to the control of societies [and its people] and is a secure gateway to power (Mokyr, 2002). Knowledge, so they say, is power.

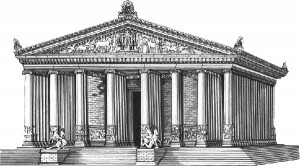

Ancient Greek Library: Artists rendition [4]

Ancient Greek Library: Artists rendition [4]

Writing, as a mode of communication, has been a hallmark of human civilization since the beginning of what has become know as history. History as a compilation of the writing of those who were in power, tracks a series of social, cultural and political transitions, involving the rise and fall of human cultures and civilizations over time as seen through the lens of those political and historical power structures and institutions. Many of the same forces [power dynamics, economics, regional and geographical realities] that shaped these historical shifts also determined the shape of the transition from Scroll to Codex.

The Primacy of The Scroll:

An ancient writing technology evolves and then fades away

The Scroll in its many forms, was used over a period of over three thousand years and as a writing and communication device, was the first record keeping technology that allowed changes, revisions and/or edits to be made. Early scrolls were developed using papyrus, a reed native to ancient Egypt, found in abundance along the banks of the Nile River and in marshes throughout the region. The Egyptians perfected the use of papyrus and developed procedures and instructions on how to best prepare it. In an elaborate process, the reeds of the papyrus plant were cut, peeled, moistened and pounded out into layers. The layers were pressed together to form sheets, left to dry and then finished, by rubbing with stones or shells, into a smooth surface suitable for writing on (Szirmai, 1990).

An example of ancient Egyptian {light} papyrus [5]

An example of ancient Egyptian {light} papyrus [5]

A significant and early form of the scroll was the ancient Hebrew text contained within the Torah [3300 BCE]. However, traditionally the use of animal skins, treated in special ways, was employed for the surface of the “page” or viewing area of the Torah. The history of the Torah Scroll, along with its many fascinating and elaborate traditions [in terms of transcription practices and protocols] is a bit of an anomalie, in terms of forms of writing in the Scroll format.

The Torah Scroll [6]

The Torah Scroll [6]

The papyrus scroll was much more common. It was developed chiefly in its early forms by the Egyptians, then modified also by the Greeks and further developed later by the Romans. Over time it became more & more refined and somewhat more practical in its applications.

Papyrus Scrolls: the medium of choice for centuries

The inherent features or characteristics of papyrus determined certain features of the Scroll. For example, only specific areas of the plant could be used for the creation of papyrus, and the size of the both the width of the scroll and its length was limited. That is, beyond certain parameters the papyrus page would simply fall apart and of course there were limits to how big a scroll could be, just as there were very real limits to how much text could be viewed at one time, as it was unrolled for reading (Szirmai, 1990).

Early Greeks like the Egyptians, recognized how important the control and storage of knowledge was to the success of an empire. Unfortunately, many of the great libraries, such as those of the Babylonians and of the early Greeks, are known to us only through descriptions of their grandeur in the writings of ancient scholars. Much as been said for example, of the great scroll based libraries of ancient cultures, such as those of Solomon and of Alexandria (Gibbons, 1877). Early recognition of the esteem in which these receptacles of knowledge were held, is reflected in the prestige which attached to the leaders who deliberately acquired them in their conquests, and to the grand and impressive architecture that was created to house them.

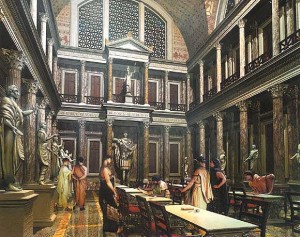

A monument to Roman Knowledge & History:

A monument to Roman Knowledge & History:

Interior of Trajan Library Artist Concept [circa 53 -177 a.d] [7]

Roman Ingenuity improves the Scroll:

By the time that the Scroll was being used by the Romans, many auxiliary technologies for the viewing and storage of the scroll had evolved. Special tables and podiums were developed which allowed for maximum viewing of areas of the scroll, and for reading and for writing on the scroll, which improved the efficiency and practicality of their use (Szirmai, 1990).

Eventually, Roman scholars and officials specified optimum measurements for scrolls, standardized its manufacture and developed guidelines for its overall appearance. Best practices included standards for width, length, colour and smoothness as well as the overall appearance of top quality scrolls. It should be noted that papyrus, throughout its time as the most favored writing medium, was always an expensive item. Writing, reading, having access to knowledge and to the materials required for writing, was the privilege only of the elite ruling classes, and was never something that the average citizen would have had access to (Roberts, C.H., 1984).

The Message is the Problem: Inherent flaws in the Medium

Part of the remediation of the scroll to codex involved the recognition by the Romans in particular, as the last great cultural inheritors of the Scroll, of some of the difficulties inherent in the medium, even with all of the accommodations, [such as special tables and podiums] that had been made. These problems including that it was difficult to move forward or backward within the scroll itself. In fact, there were many cases where this difficulty resulted in mistakes by scribes [those responsible for copying texts] who either accidentally missed sections of text [fragmentation of texts] or who unnecessarily repeated sections of text [because the section already recorded was not easily viewed].

Storage and Transport of Scrolls:

Storage of scrolls was always challenging, as noted above, it was limited by the strength of the papyrus, which delineated the maximum length of the scroll. It was a fragile medium at best, even when it was reinforced. Sticks, rods, or rollers made of wood or of ivory were inserted within the scroll to try and reinforce and support them but scrolls were always in danger of collapsing altogether or of bending and cracking in the middle (Roberts, 1984).

Papyrus scrolls could be damaged quite easily by moisture and needed special containers for both storage and transport. Sheets of papyrus that were pounded together [known as rolls, within the larger scroll] taken together, could not exceed a specific size, the maximum length was about 15 feet. It was the parameters of the technology, in terms of the maximum length for the document itself and the size and quantity of the sheets or rolls of papyrus within the Scroll that determined both how long a document it could be, and determined how it could be divided into segments or sections.

Early Greek Scroll showing wooden rolling sticks [8]

Early Greek Scroll showing wooden rolling sticks [8]

Sections or partitions of works contained within scrolls were very much defined by the medium, just as manuscripts at a later time were influenced by the format of books. These sections or partitions gradually transformed, eventually forming the familiar sections or chapters, of the codex or book. These parameters determined also the amount of viewing and writing “space” [known as the paginae, later to become the page] and the amount of text that could be communicated within the viewing area [estimated at between twenty and fifty lines] (Roberts, 1984). These characteristics became standardized features so that the work involved in unrolling and re-rolling the scroll was kept to a minimum. Even so, reading and writing using scrolls, was a fairly labour intensive activity and every time the scroll was manipulated it was at risk of being damaged.

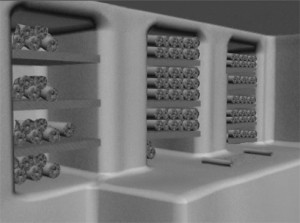

Shelving with holes in it [like the cubbyholes of a post office] was used for the storage of scrolls, but when several scrolls collected together were required [like the chapters or sections of one book] a container called a book box was employed to store the work. Marking, labeling and storing of libraries filled with scrolls was very difficult and again the limitations of the medium itself determined how many scrolls could be contained together and how they were stored.

Scroll Library of Qumran:

Scroll Library of Qumran:

Reconstruction of Qumran’s Library (illustration S. Pfann, Jr.) [9]

Pens filled with ink, were the mostly common implements used for writing on papyrus. Early pens were fashioned out of a variety of materials. Some pens were made from reeds, some were carved out of wood, and some were formed from bronze or of copper sheets that were shaped into vessels that were filled with ink. Ink was made from a variety of substances, such as ash or soot, the ink from cuttlefish or octopus, or from resin, sometimes the residue of wine [the proverbial dregs] was used for ink also (Lunsford, 2006).

A temporary alternative leads the way to a permanent solution: The Tabula Cerata

Although papyrus scrolls were expensive, difficult to edit and challenging to store and transport, fortunately, there was always, a less expensive alternative. In tandem with the advent of the scroll an auxiliary technology for short term and unofficial or casual and temporary, communication needs was used. Even during the time of the primacy of the scroll, the use of the Tabula Cerata [or the wooden writing tablet] was the medium of choice for many, such as students practicing their writing skills, for business people and merchants who had quick and frequently cryptic information to impart, and for unofficial internal government communications. These tablets usually had two leaves [two was the most common number of leaves but there could be as many as four to an upper limit of ten] which were thin pieces of birch or alder, treated with a surface of smoothed out wax that could be written or inscribed on, with a metal stylus or pen (Szirmai, 1990).

An example of the Tabula Cerata shown with stylus or wooden pen [10]

An example of the Tabula Cerata shown with stylus or wooden pen [10]

Roman Necessity as a Driver of Innovation:

As mentioned above the use of papyrus reigned supreme for a very long time, with the notable exception of the Hebrew tradition [and the production of the Torah in particular] that employed the use of parchment of made from animal skins. However, a set of circumstances caused a break in the flow of the distribution of papyrus and the resulting temporary shortage of the material in tandem with modifications to the wooden writing tablet, congealed to create an innovation, a shift, a remediation that laid the way for the final transformation of the Scroll into the Codex.

There is some controversy as to when and why there was a shortage of papyrus supplies, but there is consensus that it was the temporary inability of the Romans to import papyrus that forced a search for alternatives and resulted in the first real transition from the use of the scroll to that of the earliest forms of the Codex (Szirmai, 1990). The refinement of the early Tabula Cerata was among the many inventions and innovations of Roman culture. Parchment began to replace the more cumbersome wooden sheaves or leaves of the wooden tablet. Because of their pliability and because the leaves were so much thinner, the amount of sheets that could be contained, immediately increased, moving from [as above] the usual two, to as many as sixteen to pages within one tablet or book. It was the flexibility of the parchment that made the difference; it could be folded or bent without breaking or falling apart.

From Scroll to Tablet: From Tablet to Codex:

The early uses of these tablets remained chiefly for temporary or business communications that were brief and/or repetitive, so the early codex was used chiefly for records of business transactions and for brief official communications and letters. However, the scholars and writers of the first century soon adapted the technology, and over the first few centuries it became more and more common (Roberts, 1984). The traditional wooden tablet was transformed into a tablet with parchment leaves and then finally into a collection of leaves bound together [originally sewn together] which began to resemble the modern book.

Roman Mural: Keeping Track of the Harvest: early uses for the cerata [11]

Roman Mural: Keeping Track of the Harvest: early uses for the cerata [11]

The final remediation [which never completely eliminated the use of the scroll], was the result of more than just shortages of materials or even practical considerations of which medium would be easier to use and to store. As has been indicated in many works, (Lunsford 2006) (Roberts 1984) (Szirmai, 1990), it was the early Christian church that completed the remediation of the scroll into the Codex. Not only was the church interested in establishing the primacy of a specific work [what later became known as “The Bible”], they were also very concerned with distinguishing themselves from other religions and from those in power, specifically the Romans.

The practical aspects of the decision to adopt the codex was also relevant, that is, the entire work known as the Gospels, was more readily packaged in the form of the codex. At the dawn of the new millennia this format was critical to the early dissemination of the first versions of the bible at a time when the church was actively promoting itself across Europe and was not yet in a position of power.

Finally, it was not only important to the early church that they distinguish themselves from the Romans with their pagan traditions but it was also important to them to demonstrate that they were different from the Hebrew religion and its scroll based traditions [as noted above].

Gutenberg Bible: later version of the ever evolving Book [12]

To sum up, the remediation of the scroll to the codex, occurred in tandem with the growing dominance of the Christian faith, which had established itself as a major force by the end of the fourth century [Gibbons, 1877). Writing, as a mode of communication, has been a hallmark of human civilization since the beginning of what has become know as history. History as a compilation of Writing, tracks a series of social, cultural and political transitions, involving the rise and fall of human cultures and civilizations over time through the lens of the dominant political and historical power structures and institutions.

Many of the same forces that shaped these historical shifts also determined the shape of the transition from Scroll to Codex. However, as has been shown, the remediation of this format for communication, was not straight forward and in the end was pushed not just by practical, economic or political forces alone, but also and importantly, in this instance, by the perceived needs of an emerging religion, that was soon to become a dominant force in the history of western culture.

References:

Bolter, J.D.(2001)Writing Space: Computers, hypertext, and the Remediation of Print

Lawrence, Erlbaum Associtates Inc. Mahwah, NJ, USA

Bottero, J., Herrenschmidt, C., & Vernant, J. P. (2000). Ancestor of the West: Writing, reasoning, and religion in Mesopotamia, Elam, and Greece.

Edney, M. H. (1992). Mapping the early modern state: The intellectual nexus of late Tudor and early Stuart cartography.

ETEC 540: Module 4:Literacy and the New Media

Digital Literacy and Multiliteracies

Habermas, J. (1986) Knowledge and Human Interests Cambridge, Polity Press

Lunsford, A. A. (2006). Writing Technologies and the Fifth Canon. Computers and Composition. 23, 169–177.

Mokyr, J. (2002). The Gifts of Athena: Historical Origins of the Knowledge Economy.

Roberts, C.H. (1984) The Birth of the Codex

Oxford University Press, USA

Digital References:

Szirmai, J.A. (1990) Wooden Writing Tablets and the Birth of the Codex

Gazette du Livre Medevale, No. 17

Also: retrieved online October 2009

http://cool.conservation-us.org/byorg/abbey/an/an15/an15-4/an15-407.html

Classic Encyclopedia Online (2006) 11th Edition, Encyclopedia Britannica

http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Later_Roman_Empire

Reference: Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1877)

The British Museum Online: What is Writing?

http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/themes/writing/what_is_writing.aspx

Retrieved online: October 2009

The Israel Museum, Jerusalem: A Wandering Bible: The Aleppo codex

http://www.english.imjnet.org.il/HTMLs/article_453.aspx?c0=13815&bsp=13246

Retrieved online: October 2009

List of Digital Visual References: All images from Google Images

Retrieved: October 2009

[1] First Bible: one of the earliest versions of the Bible

[2] The Act of Writing: Artist’s conception

[3] Graffiti: Late twentieth century writing

[4] Ancient Greek Library: Artists rendition

[5] Early Egyptian Papyrus: {light type} Google Images

[6] Torah Scroll: one of the earliest parchment scrolls

[7] Trajan Library: A monument to Roman History: circa 53 – 177 a.d

[8] Early Greek Scroll: showing wooden rolling sticks

[9] Scroll Library of Qumran:

Reconstruction of Qumran’s Library (illustration S. Pfann, Jr.)

[10] Tabula Cerata: Example showing wooden stylus or pen

[11] Roman Mural fragment:

Keeping Track of the Harvest: early use of the Tabula Cervata

[12] Gutenberg Bible: example of the evolution of the Book

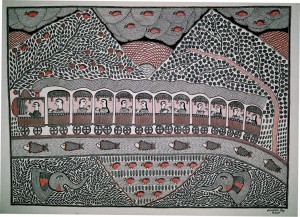

Long before there were computers in most of our homes, there was Mithila Art in homes of what is now India and Nepal. Originally, this folk art form mainly consisted of lively murals painted on the walls of homes in rural villages. But it was much more than simple art for art’s sake. “Mithila painting is part decoration, part social commentary, recording the lives of rural women in a society where reading and writing are reserved for high-caste men” (Arminton, Bindloss & Mayhew, 2006, p. 315). This was art that gave a voice to powerless rural women as a communication technology.

Long before there were computers in most of our homes, there was Mithila Art in homes of what is now India and Nepal. Originally, this folk art form mainly consisted of lively murals painted on the walls of homes in rural villages. But it was much more than simple art for art’s sake. “Mithila painting is part decoration, part social commentary, recording the lives of rural women in a society where reading and writing are reserved for high-caste men” (Arminton, Bindloss & Mayhew, 2006, p. 315). This was art that gave a voice to powerless rural women as a communication technology.