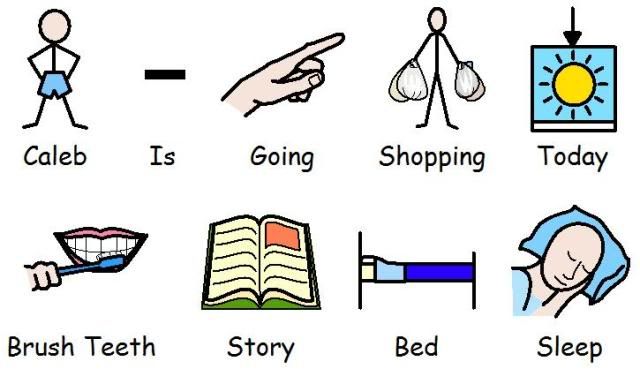

Language as Cultural Identity

Russification of the Central Asian Languages

Pier Borbone asserts that “there is no obligatory relationship between language and writing: per se, every language can be represented with any graphic system, even systems originally created for other languages – if necessary with certain adaptations.” (Borbone, 2007) He further theorizes that “the decision to adopt a certain kind of script depends to a large degree on other considerations, not having to do with the language itself, and that the choices of script made by different peoples and nations are an interesting clue to cultural, political and religious aspects of their history.” (Borbone, 2007)

The former Soviet Union provides an interesting case study when looking at cultural and political implications of using an already existent script for historically and culturally rich but very different languages which already had been using a different script. Specifically looking at the adoption of the Cyrillic alphabet to the Central Asian and Far Eastern languages, we can examine the Russification of these particular languages and cultures.

With the creation of the new Soviet Union came many challenges. One of the major challenges was to create an identity and somehow unify over 100 different ethnic groups. A systematic policy of Russification was adopted by the early Soviet government but it was by no means a new development. Russification dates back to the 16th century with the conquest of Khanate of Kazan and other Tatar areas. At its early stages, Russification mostly involved Christianization and implementation of the Russian language as the sole administrative language.

The Cyrillic alphabet was created by St. Cyril and his brother St. Methodius, who were Byzantine missionaries and were sent to convert the Slavs to Christianity. The original alphabet was known as Glagolitic from which modern day Cyrillic evolved.

Glagolitic alphabet

Cursive version of the Glagolitic alphabet

http://www.omniglot.com/writing/glagolitic.htm

1918 version

The names of the letters are in Russian.

http://www.omniglot.com/writing/cyrillic.htm

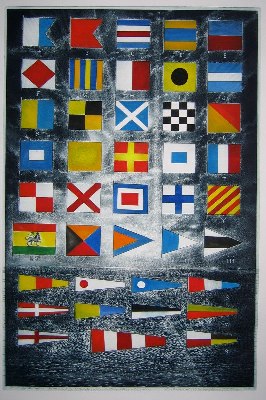

Languages written with the Cyrillic alphabet

Abaza, Abkhaz, Adyghe, Archi, Avar, Azeri, Balkar, Bashkir, Belarusian, Bulgarian, Buryat, Chechen, Chukchi, Church Slavonic, Chuvash, Dargwa, Dungan, Erzya, Even, Evenki, Gagauz, Ingush, Kabardian, Kalmyk, Karakalpak, Kazakh, Komi, Koryak, Kumyk, Kurdish, Kyrghyz, Laz, Lak, Lezgi, Lingua Franca Nova, Macedonian, Mansi, Mari, Moksha, Moldovan, Mongolian, Nanai, Nenets, Nivkh, Old Church Slavonic, Ossetian, Russian, Ruthenian, Serbian, Slovio, Tabassaran, Tajik, Tatar, Turkmen, Tuvan, Tsez, Udmurt, Ukrainian, Uyghur, Uzbek, Votic, Yakut, Yukaghir, Yupik

http://www.omniglot.com/writing/cyrillic.htm

In the early centuries, the Christian missionaries had difficulties in converting eastern Slavs to Christianity due to language barriers. The western missionaries were using Latin and the eastern missionaries were using Greek but both were foreign to the Slavs. St. Cyril (827-869 AD) developed the Glagolitic/Cyrillic script which made the conversion process much simpler. The brothers modeled Glagolitic alphabet on a cursive form of Greek. The Glagolitic alphabet evolved into Old Church Slavonic which “was used as the liturgical language of the Russian Orthodox Church between the 9th and the 12the centuries.” (Blech, 2008) Currently the Russian Orthodox Church uses Church Slavonic which appeared during the 14th century. There are some speculations that the Old Church Slavonic may have been invented by St. Kliment of Ohrid based on the Glagolitic alphabet.

The current form of the Cyrillic alphabet came into being in 1708 during Peter the Great’s westernization and secularization campaigns. The newly modified alphabet was known as grazhdanka.

The 1917 Russian revolution paved the way for the inception of the Soviet Union in 1922 which united several republics under one umbrella. After 1922, the authorities decided to eradicate the use of the Arabic alphabet in Turkic and Persian languages in the Soviet-controlled Central Asia, in the Volga region, including Tatarstan, and in the Caucasus.

This drastic change was well thought out because it detached the local population from the exposure to the language and writing system of the Koran. This served a twofold purpose of curbing religious activities and further separating the local population from their ethnically closer groups in other Middle Eastern countries. As well it prevented the “formation of alternative ethnically based political movements, including pan-Islamism and pan-Turkism.” (Absoluteastronomy, 2009)

A very effective way of accomplishing this was to “promote what some regard as artificial distinctions between ethnic groups and languages rather than promoting amalgamation of these groups and a common set of languages based on Turkish or another regional language.” (Absoluteastronomy, 2009)

The new alphabet was inspired by the Turkish alphabet and was based on the Latin alphabet. However, in 1939-1940, the policy changed and it was decided to change Tatar, Kazakh, Uzbek, Turkmen, Tajik, Kyrgyz, Azeri and Bashkir languages and make them use variations of the Cyrillic alphabet. It was claimed that the switch was made “by the demands of the working class.” (Absoluteastronomy, 2009)

In the Soviet Union the Latin alphabet was first officially introduced in Soviet Azerbaijan in 1925 13, and a “Unified Turkic Latin Alphabet” for all the Turkic languages of Soviet Central Asia followed between 1927 and 1930. In the second half of the 1930s the policy was changed, and a campaign began to introduce, in place of the unified Latin alphabet, several Cyrillic alphabets somewhat different for each Turkic language. For instance, the Cyrillic alphabet for the Uighur language consisted of 41 letters – the Latin one being of 32. (Winner, 1952)

Since the Soviet government decided that a nation was defined by the existence of a language, a language had to be selected each time it was decided that there was to be a nation. This activity produced considerable problems. One of the major ones was the fact that dialectic differences had to be accentuated between the populations of a single linguistic area. Each nation was constructed on the basis of difference.

The most ludicrous case was the separation created between Tajik and Persian. The Tajik used literary Persian as their written language. There exists a perfect comprehensibility between the literary languages current in Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan. However, in their daily lives the Persian speakers of Central Asia use dialects which vary considerably. The relationship between Iranian and Tajik Persian is similar to the relationship between Persian French and Quebecois. Russian linguists had to formalize and fix differences and to invent a modern literary Tajik language. Instead of taking one of the existing Tajik dialects as their standard, they created an artificial language which combined characteristics from different regions. They kept the phonological system of Old Persian, but adopted grammatical variations which highlighted the difference with Iran.

Uzbek was also severely manipulated. It was linked with Kazakh and Tatar which have the least similarities with Uzbek. Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan were quick to adopt Latin script, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan delayed the switchover, and both still use Cyrillic.

The situation is different for the Turkic-speaking peoples of the Soviet Union. The use of various modified Cyrillic alphabets, in this case with variations for the Azeri, Kazakh, Turkmen, Kyrgyz languages, was the norm at the time of the break-up of the Soviet Union. Nowadays the various independent states each go their separate ways: in Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan a modified Latin alphabet is used, while in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan the Cyrillic ones are still used. Obviously to some extent these choices reflect the political relationships that exist, or are desired, with Russia and Turkey.

The 20th century is one in which national languages have rapidly developed and increased in number. If we speak about European national languages, they have increased nearly threefold (from 16 to 50) in something more than 100 years. In Central Asia, if only the Turkic language writing systems are taken into consideration, the unified literary language (Chagatay Turkic) developed into 30 different literary languages.

Ong asserts that “more than any other single invention, writing has transformed human consciousness.” (Ong, 2000, p.77) He further states that “writing establishes what has been called ‘context-free’ language … or ‘autonomous ‘ discourse, discourse which cannot be directly questioned or contested as oral speech can be because written discourse has been detached from its author.” (Ong, 2000, p.77)

The result of this manipulation of languages was loss of local languages and cultures. The official policy of sending Russians to non-Russian speaking republics resulted in the local population adopting Russian language and culture while Russian people did not learn local languages or partake in the local cultures. To do so was considered backward. When non-Russian speakers moved to another non-Russian republic, they learned Russian instead of the local language. For example 57% of Estonia’s Ukrainians and 70% of Estonia’s Belarusians claimed Russian to be their native language in the 1989 Soviet census.

Patterns of linguistic and ethnic assimilation (Russification) were complex and cannot be accounted for by any single factor such as educational policy. Also relevant were the traditional cultures and religions of the groups, their residence in urban or rural areas, their contact with and exposure to Russian language and to ethnic Russians, and other factors.

There is strong evidence to suggest that language was viewed as the first attack in the government’s Russification policy because it is very closely tied with who we are, individual identity and the identity of a group. Changing a language eventually brings about changes in culture and thinking. Changing a script in a particular language to another aligns that language and culture with the dominant culture.

References

Absolute Astromony: Exploring the Universe of Knowledge. (2009) Russification. Retrieved October 3, 2009, from http://www.absoluteastronomy.com/topics/Russification

Allworth, A. Ed. (2002). 130 Years of Russian Dominance, A Historical Overview . Duke University Press. Retrieved October 2, 2009, from Google Books http://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=X2XpddVB0l0C&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=use+of+cyrillic+alphabet+in+central+asia&ots=-95SLd9pSF&sig=QTiOnWJkrczLApCu-d6ffsl9aEM#v=onepage&q=use%20of%20cyrillic%20alphabet%20in%20central%20asia&f=false

Blech, A. (2008) The Russian Orthodox Church: History and Influences. Retrieved October 23, 2009, from http://www.utexas.edu/cola/centers/creees/_files/pdf/curriculum/CREEES-developed-units/russian_orthodox.pdf

Bodrogligeti, A. (1993). Dissolution of the Soviet Union: The Question of Alphabet Reform for the Turkic Republics. Azerbaijan International, 1.3, 16-17. Retrieved October 28, 2009 from http://azer.com/aiweb/categories/magazine/13_folder/13_articles/13_sovietunion.html

Borbone, G. P.(2007). Choice of Script as a Mark of Cultural or/and National Identity. Retrieved October 18, 2009, from http://www.stm.unipi.it/programmasocrates/cliohnet/books/language2/02_Borbone%201.pdf

Burghart, D. L., (?/) In the Tracks of Tamerlane: Central Asia’s Path to the 21st Century. Retrieved October 5, 2009, from http://ndu.edu/CTNSP/tamerlane/Tamerlane-Chapter1.pdf

Eurasia Insight. (2006) President Ponders Alphabet Change in Kazakhstan. Retrieved October 24, 2009, from http://www.eurasianet.org/departments/insight/articles/eav111706b.shtml

Omniglot: Writing Systems and Languages of the World. (2009). Retrieved October 27, 2009, fromhttp://www.omniglot.com/writing/glagolitic.htm

Omniglot: Writing Systems and Languages of the World. (2009). Retrieved October 27, 2009, fromhttp://www.omniglot.com/writing/cyrillic.htm

Ong, W. J., (2000). Orality and Literacy. New York: Routlage.

Winner, T. G.(1952). Problems of Alphabetic Reform Among the Turkic Peoples of the Soviet Central Asia, 1920-1941. The Slavonic and East European Review, 76, pp. 133-147.