Through equal parts careful examination and applied imagination, tracing the effects of codices’ change from manuscripts to printed text is possible. This reformation altered the very situation of codices in society. The explosion of access precipitated by the printing press also changed the very nature of consuming information.

According to Benjamin in his seminal work Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, a “tremendous shattering of tradition” is one result of the m reproduction possible post-Gutenberg. The “aura” or uniqueness is lost (1936). This abstract notion is difficult to grasp and could be considered too amorphous to define differences between manuscripts and printed text. However, further support comes from more concrete corners. Pre-Gutenberg chirography details the numerous writing systems in simultaneous use by one society. Salen (2001) details these multiplicities. For example, Early Rome had three formal writing systems each meeting a specific textual need. Discerned through this research is, “the inscription of language by human hands involved practices in which value and meaning were assigned not to just what was written, but how it was written” (p. 134). Printed text cannot share in these characteristics; something is lost in translation from manuscripts to printed text. The move disconnects readers from the “discovery of that magical moment of creation” (Trachsler, 2006, p.7). The philologists use their own, distinct phrases to communicate their stand: “pretty books” and “ugly or dirty manuscripts”. But those same ugly manuscripts reveal the creative process, “those chartae and pages with all their cross-outs, deletions, erasures, marginalia, and insertions that reveal the author’s hand in the struggle of artistic creation” (Storey, 2006, p. 3). Whether you align with the philologists or the chirographers, something is lost when the flow of many hands writing is replaced by a single machine printing.

The move from manuscripts to printed books also re-located the reader. Ong in his chapter “Writing Restructures Consciousness” explores the effect of changing textualities. “Early writing provides the reader with conspicuous help for situating himself imaginatively” (2002, p.102). Eventually the reader must disengage with the printed book, as there is a shift in the senses. Pre-Gutenberg manuscripts contained residual orality – they stemmed from and recorded the spoken word. Added to this were the illuminations and very flow of the script immersing the reader into a multi-sensory experience. The reader seemed invited into a conversation through reading. Printed books were confined to the visual and the delivery of the text reflected this. [See Ong, Chapter 4]

Manuscripts were possessed by the few and the knowledge disseminated to the many. This closed system, where what was worth knowing and preserving, seemed clearly defined by the efforts of scribes, provided a sense of security (McLuhan, 1962). The flow of information was top down. Gutenberg’s printing press removed established means of selection and unlocked the flood gates – the first information overload. Readers no longer savoured the content of a manuscript; soon they were able to sip from many selections. Consuming text also became a solitary, independent exercise, independent of the usual sites of practice – universities, church, or crown. The force of these sites of practice to dictate what information was shared diminished. Rather than loyal scribes capturing the knowledge, the printing press became the new amanuensis and loyalty was scarce. “Multiplication was one of the main points in the praise of the new invention” (Widmann, 1972, p. 253), but the technology that had the capability to retain knowledge for everyone and for always did not fulfill its promise. The explosion of printed knowledge actually decreased the value of that knowledge. The written tradition soon fell prey to supply and demand. As the price and investment of print decreases, anyone can be an author; it is no longer an exalted position held by scholars and religious leaders. The marketplace floods (Mueller, 1994; Swierk, 1974). Rather than knowledge being preserved through this more stable medium, texts fell out of favour as quickly as they had achieved popularity. The printed book becomes a commodity, subject to the whims of society rather than a communication tool for knowledge.

“Setting type also emphasizes the importance of the letter as the basic unit of written forms, as an element in its own right with particular characteristics and not only as the representation of the patterns of spoken language” (Drucker, 1984, p. 11). The whole starts to separate and break down into many parts. Again, the flow is interrupted when codices change from manuscript to print. Once one begins to view something differently such as fragments rather than a whole, how one interacts with it is open to change as well. Engaging with the text no longer resembles a conversation; the text grows into an object to be acted upon. “Print suggests that words are things far more than writing ever did” (Ong, 2002, p. 116). Commoditization of text happens in another form.

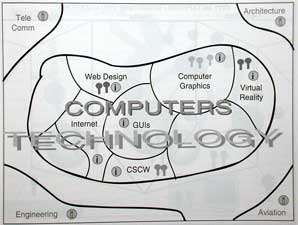

One of the most striking examples of changing attitudes toward texts is the increased use of indexes. Pre-Gutenberg, indexing was inefficient and ineffective. “Two manuscripts of a given work, even if copied from the same dictation, almost never correspond page for page” (Ong, 2002, p. 122). The precision possible Post-Gutenberg provided a radical change. No longer did texts need to be digested whole or scanned closely. Indexing as way finding allowed a reader to jump in and jump out as s/he saw fit. Although this information architecture allowed the reader to zero in on items of most interest, it also fragmented the text. What once were global understandings and deep interactions with a text became analytical pieces and short exchanges.

The combination of the explosion of texts and the different means of access led to fundamental changes. Previously, a person would be exposed to a limited number of manuscripts, but most likely would continue to explore their meanings and apply the wisdom gained from close scrutiny. With the post-Gutenberg information overload merging with the growing popularity of organization through indexing, breadth overtook depth. The natural conclusion to this was that it became more likely a person would know a few things about a great many subjects rather than know a few subjects in great detail.

I’ve attempted to give you a glimpse into how changing the visual representation may affect a person. Please follow this link if you’re interested.