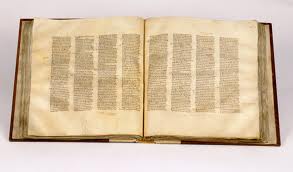

Educational textbooks date back to the founding of the first Church schools in England in 700 CE. (Carpenter and Pritchard, 1984) Latin was the language of the Church and English state, and thus indispensible to the education of Old English-speaking young men entering the Church’s monastic orders.

Teaching reading and writing in the medieval Church was delivered with the aid of Latin primers and grammar texts, as well as books covering the basic alphabet, songs and liturgical prayers for youngsters. Such books contained collections of well-known dialogues, sayings and quotations from classical authors that were memorized and recited by rote. The predominant mode of pedagogy for younger students was the question and answer format, or catechism, which required only one manuscript textbook with little or no supporting materials or outside knowledge on the part of the teacher. (Wakefield, 1998)

One of the most important early textbooks is The Grammar and Colloquy of Ælfric (1006 CE), which served as a manual of Latin grammar and glossary intended for young pupils. Ælfric’s school book is exceptional because it is set as an entertaining dialogue between some lay-person students and their teacher (Carpenter and Pritchard, 1984). With the rise of medieval universities in England between the 12th and 16th centuries, textbooks began to include manuals on logic and rhetoric in Latin based on classical models. Textbooks were also created to train Latin students in verbal fluency and rhetorical skill. They were part of the medieval curriculum of the Trivium and Quadrivium, intended to provide training in the liberal arts by including arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music. (Fideler, 1996)

During the 16th century, Elizabethan Grammar Schools educated the boys of the nobility from ages 7 to 14. One specialized type of textbook used in teaching younger children was the horn-book, which was built from a wooden board and handle protected by a horn cover with printed ABC’s, grammar lessons or prayers pasted on parchment. (see Fig. 1) The first English-language manuals of Latin grammar and syntax were also put into use during Elizabethan times, which led to the standardization of William Lily’s Grammar (1540) as the only authorized Latin teaching text by order of Henry VIII. This textbook remained in use for over two hundred and fifty years in English universities and Grammar Schools. (Carpenter and Pritchard, 1984)

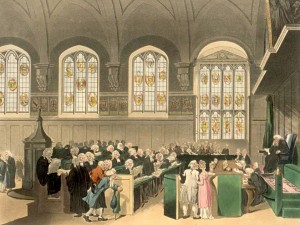

The Enlightenment ushered in some profound changes in English education during the 18th C, including the addition of teaching in English alongside Latin, and the beginning of the textbook publishing industry among booksellers. Illustrated primers for younger children began to be published, and there was a rise in overall opportunities for gaining literacy, book ownership and home-based instruction in England. At the same time, certain Enlightenment philosophers questioned the value of rote memorization and the rigid, limited classical curricula of English schools. John Locke proposed that education should cultivate both the mind and body, and that it be directed toward achieving broad vocational and social purposes in line with citizens’ natural rights to life, liberty and property.

The late 18th century also saw a change in the English-language textbooks used in the United States that stemmed from the Enlightenment philosophies and nationalism which inspired the American Revolution. Religious instruction was combined with teaching of American language, spelling, and pronunciation as distinguished from English models (e.g., a famous example is Noah Webster’s American Spelling Book). (Chall & Squire, 1996)

An important development of the Victorian period in the English-speaking world was the publication of children’s textbooks and readers that presented historical, geographical and scientific facts and information, rather than just religious instruction, though moral instruction was a common feature of children’s books that taught reading through stories (Wakefield, 1998, 11-14). This differed between boys and girls among the upper classes that could afford education, however, as private home-instruction by tutors and governesses for girls mainly consisted of hours of memorizing a limited range of questions and answers from popular instructional books.

Textbooks introduced during this time in the English-speaking world responded to advances in educational philosophy, the rise of regional schools systems, the professionalization of teaching, and the introduction of standardized curricula, all of which have continued to be central concerns in modern textbook editing, publication and instructional design. (Fagan, 1980)

Anthologies and Introduction of Literature into the School Curriculum

The introduction of teaching anthologies as classroom textbooks coincides with a change that occurred in the late 19th century in Britain, and other parts of the English-speaking world, which saw the addition of literature a field of study in the school curriculum and provided a transition from the moralistic instructional readers of the Victorian period.

The age-old need to teach reading and writing created the opportunity to use literary works as teaching tools in widely available textbook formats, of which the literary anthology was a new development. The change to textbook-format literary anthologies presented students with samples and specimens of writing in their original form, either with or without abridgment, in a way that differed from the miscellaneous format of the Latin readers. Also, the anthology type of textbook was not as well suited to memorization and repetition as the miscellany; it was better suited to the modern pedagogical practices of selective reading and teacher-directed comparative study.

Literary anthologies have been used in mass education in the 20th Century because they provide formats for shorter works (the story, the essay, the poem) in a single volume. They also may be structured around broad sweeps of time, thus presenting a continuous survey of distinct historical periods, and enable a juxtaposition of texts in one volume that can compare and contrast the growth of literary techniques and periods. (Banta, 1993) In addition, modern anthologies may include supplementary resources in the form of footnotes, illustrations, glossaries, historical maps, and other apparatus. For these reasons, literary anthologies are now the standard textbook format for introducing literary works to students from elementary school through to university courses. (Hook, 1971)

On the other hand, literary anthologies have a history of their own stemming from imitations of the classical model (anthology translates from the Greek root: anthos flower +legein to gather) of collecting poems and songs into single volumes. The practice of assembling poetry anthologies, both as classical translations and in English, goes back to Elizabethan times (Ferry, 2001). The format was revived in the 19th century as gatherings of “representative” poetry selections gathered on historical, national or aesthetic themes for home reading. The most prominent and widely read of these was Palgrave’s Golden Treasury (1861). It set the popular mark for incorporating poems on both a historical basis, genre and verse forms (e.g. lyric, sonnet, ode), as well as covering different expressions of feeling and subject matter that would appeal to different types of readers.

This second current in anthology publication involved considerations that were beyond any given anthology’s merits as a classroom textbook. In the United States in the 1920’s, for example, there was a mass movement driven by immigration to provide educational textbooks in literature that were distinctly American, not British, which also would reflect the transition to Modern writing of the era. This created market of teaching anthologies for schools and colleges that was addressed by a number of important American Modernist poets and editors of the time (Abbott, 1990).

Anthologies were instrumental in the canon formation of English-speaking literatures, which is essentially the consensus among authors, critics, publishers and the reading public about what makes a literary work “great”, “timeless” or “representative” of a particular historical period. The matter of canon formation in literary textbook anthologies is far from being settled, however. (Pace, 1992) Because textbook anthologies can confer status and acceptance on a work simply by their choices of what to present to a large and impressionable audience, they can also serve the “gatekeepers of the fortress of high culture” (Landow, 1989) by keeping certain works out of the literary canon. For this reason, widely used modern general anthologies such as the contemporary The Norton Anthology of English Literature (M.H. Abrams editions), are acutely aware of the issues and controversies involved in surveying works by women, minorities, post-colonial and indigenous cultures, and different national literatures. (Mujica, 203-4)

References

Abbott, C.S. (1990) Modern American Poetry: Anthologies, Classrooms, and Canons. College Literature, 17(2/3), 209-221.

Banta, M. (1993). Why Use Anthologies? or One Small Candle Alight in a Naughty World. American Literature, 65 (2), 330-334.

Carpenter, H., & Prichard, M. (1984). Books of Instruction. In The Oxford Companion to Children’s Literature (pgs. 73-74). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chall, J. & Squire, J. (1996). The Publishing Industry and Texbooks. In R. Barr, M. Kamil, P. Mosenthal, &P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (pgs. 121-122) New York: Longman.

Fagan, E.R. (1980). Textbooks and the Teaching of English. The English Journal, 69(5), 27-29.

Ferry, A. (2001). Tradition and the Individual Poem: An inquiry into anthologies. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Fideler, D. (April 27, 1996) The Seven Liberal Arts. Retrieved from http://cosmopolis.com/villa/liberal-arts.html

Hook, F. (1971). The Anthology: To Be or Not to Be. English Education, 2(2), 105-109.

Landow (1989) The Literary Canon. Retrieved from http://www.victorianweb.org/gender/canon/litcan.html

Mujica, B. (1997) Teaching Literature: Canon, Controversy, and the Literary Anthology. Hispania, 80(2), 203-215.

Pace, B.G. (1992) The Textbook Canon: genre, gender, and race in US Literature anthologies. The English Journal, 81(5), 33-38.

Wakefield, J.F. (1998). A Brief History of Textbooks: Where have we been all these years? Paper presented at the meeting of the Text and Academic Authors (pgs. 1-29). Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov.proxy.lib.wayne.edu/PDFS/ED419246.pdf