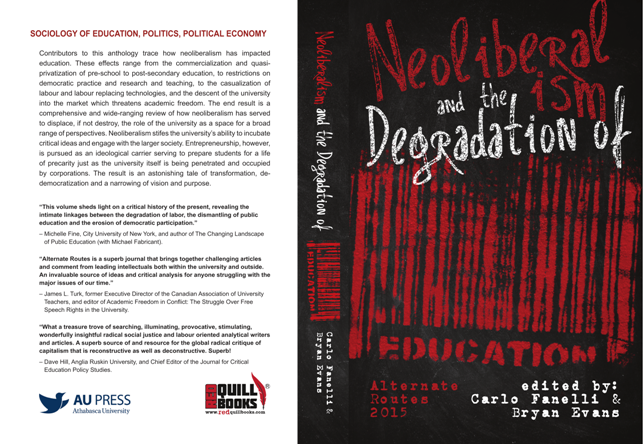

Edited by:

Paul R. Carr, Université du Québec en Outaouais

Brad J. Porfilio, CSU, East Bay

A volume in the series: Critical Constructions: Studies on Education and Society. Editor(s): Curry Stephenson Malott, West Chester University of Pennsylvania, Brad J. Porfilio, California State University, East Bay, Marc Pruyn, Monash University, Derek R. Ford, Syracuse University.

Published 2015

Anyone who is touched by public education – teachers, administrators, teacher-educators, students, parents, politicians, pundits, and citizens – ought to read this book, a revamped and updated second edition. It will speak to educators, policymakers and citizens who are concerned about the future of education and its relation to a robust, participatory democracy. The perspectives offered by a wonderfully diverse collection of contributors provide a glimpse into the complex, multilayered factors that shape, and are shaped by, education institutions today. The analyses presented in this text are critical of how globalization and neoliberalism exert increasing levels of control over the public institutions meant to support the common good. Readers of this book will be well prepared to participate in the dialogue that will influence the future of public education in United States, and beyond – a dialogue that must seek the kind of change that represents hope for all students.

As for the question contained in the title of the book – The Phenomenon of Obama and the Agenda for Education: Can Hope (Still) Audaciously Trump Neoliberalism? (Second Edition) –, Carr and Porfilio develop a framework that integrates the work of the contributors, including Christine Sleeter and Dennis Carlson, who wrote the original forward and afterword respectively, and the updated ones written by Paul Street, Peter Mclaren and Dennis Carlson, which problematize how the Obama administration has presented an extremely constrained, conservative notion of change in and through education. The rhetoric has not been matched by meaningful, tangible, transformative proposals, policies and programs aimed at transformative change, and now fully into a second mandate this second edition of the book is able to more substantively provide a vigorous critique of the contemporary educational and political landscape. There are many reasons for this, and, according to the contributors to this book, it is clear that neoliberalism is a major obstacle to stimulating the hope that so many have been hoping for. Addressing systemic inequities embedded within neoliberalism, Carr and Porfilio argue, is key to achieving the hope so brilliantly presented by Obama during the campaign that brought him to the presidency.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments. Foreword: Barack Obama’s Neoliberal War on Public and Democratic Education (2014, for the second edition), Paul Street. Foreword: Challenging the Empire’s Agenda for Education (2011, for the first edition), Christine Sleeter. Introduction: Audaciously Espousing Hope (well into a second mandate) Within a Torrent of Hegemonic Neoliberalism: The Obama Educational Agenda and the Potential for Change, Paul R. Carr and Brad J. Porfilio.

SECTION I: USING HISTO RICAL AND THEORETICAL INSIGHTS TO UNDERSTAND OBAMA’S EDUCATIONAL AGENDA. Even More of the Same: How Free Market Capitalism Dominates Education, David Hursh. “The Hunger Games”: A Fictional Future or a Hegemonic Reality Already Governing Our Lives?Virginia Lea. Ignored Under Obama: Word Magic, Crisis Discourse, and Utopian Expectations, P. L. Thomas. The Obama Education Marketplace and the Media: Common Sense School Reform for Crisis Management, Rebecca A. Goldstein, SheilaMacrine, and Nataly Z. Chesky.

SECTION II: THE PERILS OF NEOLIBERAL SCHOOLING: CRITIQUING CORPORATIZED FORMS OF SCHOOLING AND A SOBER ASSESSMENT OF WHERE OBAMA IS TAKING THE UNITED STATES. Charter Schools and the Privatization of Public Schools, Mary Christianakis and Richard Mora. Undoing Manufactured Consent: Union Organizing of Charter Schools in Predominately Latino/a Communities, Theresa Montaño and Lynne Aoki. Dismantling the Commons: Undoing the Promise of Affordable, Quality Education for a Majority of California Youth, Roberta Ahlquist. Obama, Escucha! Estamos en la Lucha! Challenging Neoliberalism in Los Angeles Schools,Theresa Montaña. From PACT to Pearson: Teacher Performance Assessment and the Corporatization of Teacher Education, Ann Berlak and Barbara Madeloni. Value-Added Measures and the Rise of Antipublic Schooling: The Political, Economic, and Ideological Origins of Test-Based Teacher Evaluation, Mark Garrison.

SECTION III: ENVISIONING NEW SCHOOLS AND A NEW SOCIAL WORLD: STO RIES OF RESISTANCE, HOPE, AND TRANSFORMATION. The Neoliberal Metrics of the False Proxy and Pseudo Accountability, Randy L. Hoover. Empire and Education for Class Consciousness: Class War and Education in the United States, Rich Gibson and E. Wayne Ross. Refocusing Community Engagement: A Need for a Different Accountability, Tina Wagle and Paul Theobald. If There is Anyone Out There…, Peter McLaren. Afterword: Working the Contradictions: The Obama Administration’s EducationalPolicy and Democracy to Come (from the 2011 edition), Dennis Carlson. Afterword: Barack Obama: The Final Frontier, Peter Mclaren. Afterword: Reclaiming the Promise of Democratic Public Education in New Times, Dennis Carlson.About the Authors. Index.