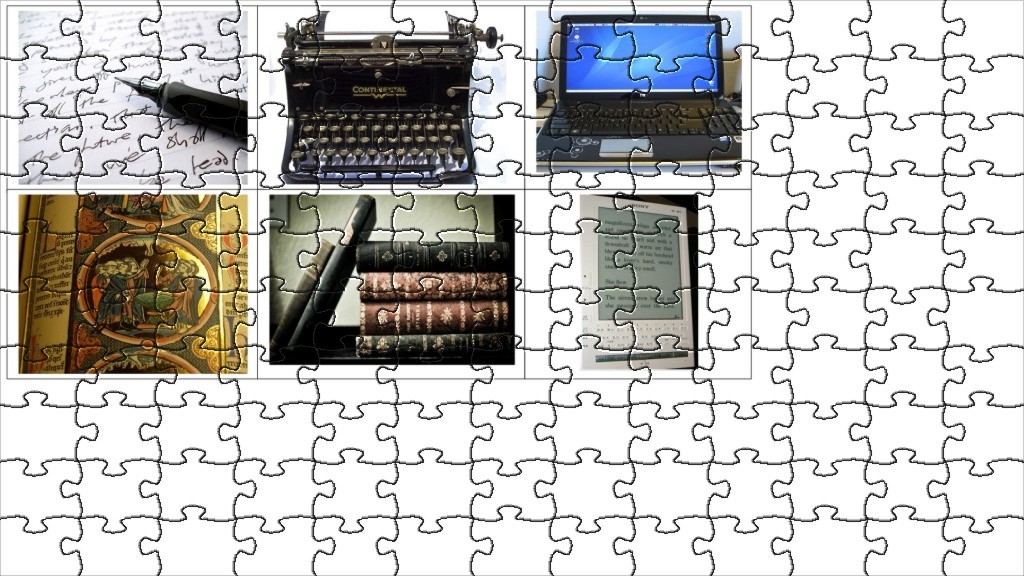

In Chapter 5, The Electronic Book, Jay Bolter (2001) explores the notion of the “The Changing Idea of the Book”. He rightly states that by changing the technological form of the book, the reader, writer, as well as related organizational structures will experience change. According to Bolter (2001), for the remediation of the paper book to the electronic book (e-book) to be successful the latter must offer something more than the former. He suggests the e-book offers a couple of advantages – hypertext to look up words and the ability of e-readers to hold numerous books whereas traditional books are self contained. Bolter (2001), notes that national libraries for years have been actively building digital sources thereby demonstrating their value with traditional and digital structures. However, the emergence and advancement of organizational structures in the digital era present a potential challenge to library structures as the primary repositories of books. Anthony Grafton (2007), in his article Future Reading Digitization and its discontents highlights the scope of digitalization projects by various organizations such as Google, Microsoft and Amazon. Consequently, the advancement of the e-book, including the digitalization of old books, has the potential to fundamentally change post secondary education, in particular libraries.

Since Bolter (2001) wrote this chapter on e-books, there have been dramatic technological advances that have greatly enhanced the benefits of e-readers. In addition to increased models, the advancements in mobile technologies have resulted in considerable improvements in the readability, providing colour options, increased memory, and devices that are multifunctional. Many e-readers use an E-Ink that permits the e-book to be read in bright sunlight and does not provide the glare and is much easier to read.

As suggested by Bolter (2001), e-book’s are influencing organizational structures. According to Steve Haber, the head of Sony’s digital reading business division, the growth is expected to continue “Within five years there will be more digital content sold than physical content. Three years ago, I said within ten years but I realized I was wrong – it’s within five”(Richard, June 2010). CourseSmart – an on-line e-book distributor – claims that e-book subscriptions have increased by 400 percent from 2008 to 2009 (Educause, 2010). The Association of American Publishers announced e-book sale revenues increased from 46.6 million in January 2008 – October 2008 to 130.7 million in January 2009 – October 2009 for a 180.7% increase with predictions that it will reach 500 million by the end of 2010 (not including professional markets such as libraries and educational institutions (Kho, 2010).

The consumer market has demonstrated the feasibility of reading on these devices, thus opening an opportunity for them to be used in the university environment (Princeton Report, 2009). This, in part, speaks to the mega projects by Google, and other organizations to digitize old books. According to Anthony Grafton (2007), the estimated global volume of books range from 32 million to 100 million books. However, these organizations are driven by the profit motive, and are potentially competitive organizations with university and national libraries, thus having the influence to change library organization structures. “Google and Microsoft pursue their own interests, in ways that they think will generate income, and this has prompted a number of major libraries to work with the Open Content Alliance, a nonprofit book-digitizing venture” (Grafton, 2007, pg4.) By collecting as many books as possible libraries have traditionally been the holders of knowledge (Bolter, 2001) however, the digitalization projects present serious competition as the repository of digital content.

Nonetheless, the university and college sectors are integral to the advancements and profitability of e-book market as evidenced by Springer Publishing’s investigation in to its e-book program. According to Springer data, libraries and universities are responsible for 63 percent e-book traffic (van der Velde & Ernst, 2009). This is further demonstrated in JISC national e-books observatory project (2009) that surveyed 52,000 respondents about e-book usage. The respondents identified the university library being the source of the e-books at 51.9 percent (pg. 13). HighWire Press conducted a 2009 Librarian E-book Survey that determined the market in the education sector is starting to make a reallocation of resources to the e-book market. Most of the respondents indicated that they have large budgets – 79% in excess of $250,000 for digital resources – yet they also noted that in most cases a small percentage is allocated to e-books. However, the table below highlights the anticipate shift toward increased investment in e-books (HighWire Report, 2009).

Budget Allocation for E-book Acquisitions

| Budget Acquisitions |

2009 Current Acquisitions |

E-book Acquisitions

In 5 years |

Percentage Change |

|

|

|

|

| 0% |

14 |

3 |

-78.5% |

| 1% – 10% |

77 |

20 |

-78% |

| 11% – 25% |

12 |

55 |

+450% |

| 26% – 50% |

6 |

20 |

+333% |

| 51% – 75% |

0 |

6 |

+600% |

| >75% |

1 |

5 |

+500% |

| Decline to Answer |

26 |

27 |

|

| Total |

136 |

136 |

|

Source: HighWire Press 2009 Librarian eBook Survey (pp.8 & 9)

The above table demonstrates the potential for a significant budget allocation toward e-books and a paradigm shift for students, libraries, not to mention publishers.

Notre Dame e-Reader Study

The increased importance of digital content is reflected by Joe Murphy, Yale University science librarian when he states “the only time print is relevant is when it’s not yet available digitally”(Hadro, February 2010). Nonetheless, Grafton, makes a valid argument for the contributing value of original book copies. Grafton suggests any dedicated reader will have two paths – the broad easy one of digitalization and traditional method of accessing physical books in a library, for example. He cites John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid regarding the “social life of information”, thus suggesting that “the form in which you encounter text can have a huge impact on how you use it” (cited in Grafton, 2007, pg.6). For example, the book binding can inform one who owned a book, as well as, their socio-economic status within society (Grafton, 2007). Frequently, I have read comments about the tactile benefits of having a book in one’s hand, rather than merely reading content on a screen, thus supporting the point that there is a social life of information beyond the content within the technological device.

These points leave me reflecting on Neil Postman’s (1992) argument that technology will change the culture. This shift is also reflected by some educational leaders, such as Case Western Reserve’s President Barbara Snydor stating that “we believe e-Book technology has significant potential to change the way students learn” (Reyes, July 2009 ). These comments imply a positive development however, Postman and Grafton’s observations suggest that such assumptions should not be readily accepted by educational organizations and/or students. Grafton’s emphasis on the social life of information is something I’ve experienced conducting hours of searching journal stacks, experiencing a journey of sorts as I sought out relevant information, whereas, now I conduct relatively narrow searches of electronic data bases. No longer are there the distractions of inadvertently coming across an interesting article that temporarily sidetracks the information search for the academic research paper. Grafton (2007), states that “if you want deeper, more local knowledge, you will have to take the narrower path”, thus meaning the hands-on in the library search (pg.6).

How will digitization change the learning experience in post secondary education? What is the potential loss? Is the potential loss the in-depth experience with the process of learning?

References

Bolter, J. D. (2001). Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print. Second Edition. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Educause Learning Initiative. (March, 2010). 7 Things You Should Know About E-Readers. Retrieved from http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ELI7058.pdf

Grafton, A. (2007). Digitization and its discontents. The New Yorker, November 5, 2007, pp. 1-6. Retrieved from November 16th, 2010 http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2007/11/05/071105fa_fact_grafton?printable=true

Hadro, J.(2010).Top Tech Trends: User Expectations and Ebooks. Library Journal, 135(3), 18-20. Retrieved from Academic Search Complete database. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=48227835&site=ehost-live

HighWire Stanford University (2009) 2009 Librarian eBook Survey. Retried from http://highwire.stanford.edu/PR/HighWireEBookSurvey2010.pdf

JISC Final Report. (2009). national e-books observatory project. Retrieved from http://www.jiscebooksproject.org/

Kho, N. (2010). E-Readers and Publishing’s BOTTOM LINE: The Opportunities and Challenges Presented by the Explosion of the E-Reader Market. EContent, 33(3), 30-35. Retrieved from Academic Search Complete database. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=49011059&site=ehost-live

Postman, N. (1992). Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. New york: Vintage books.

Reyes, D. (2009). Amazon releases new eBook reader aimed at educational market. New York Amsterdam News, 100(28), 29. Retrieved from Academic Search Complete database. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=43308678&site=ehost-live

Richards, S. (2010, June) Sony: ebooks to overtake print in five years. Telegraph. Retrieved from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/sony/7798340/Sony-ebooks-to-overtake-print-within-five-years.html

The Trustees of Princeton University.(2010) The E-reader pilot at Princeton Final Report. Retrieved from http://www.princeton.edu/ereaderpilot/eReaderFinalReportLong.pdf

van der Velde, W., & Ernst, O. (2009). The future of eBooks? Will print disappear? An end-user perspective. Library Hi Tech, 27(4), 570-583. Retrieved from Education Research Complete database. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=48075734&site=ehost-live

Commentary 3

Text vs. The Visual

“The reports of my death may be greatly exaggerated.” Mark Twain

Comments on the shifting nature of literacy

By Laura Bonnor

The nature of writing, reading and text are certainly changing as a result of recent technological developments. However, Bolter seems premature to predict the demise of written text in his chapter, “The Breakout of the Visual”. (Bolter, 2001) As Kress states in “Gains and Losses”, these changes must be “seen in the wider framework of economic, political, social, cultural and technological changes.” (Kress, 2005) A decade in the technology race makes quite a difference and new technology such as smart phones and blogs have brought text back to the foreground. Bolter discusses the increasing significance of visuals, pictures and icons in our hyper-textual computer-based society and sees this as ultimately leading to the end of text as we know it. Kress and Hayles note this change as well, but rather than seeing as the end of a battle where text finally loses, they see it as the remediation and negotiation process. Although Bolter refers to the remediation process, in his view, text ultimately loses ground to hyper-mediated visuals. He calls this era, “the late age of print” and muses in the last chapter about the potentially “late age of prose”. It’s interesting to note that although he predicts the end of print, he chose to write a book and that although he has created a website to accompany the book he has done it in such a way as to “not seek to render the printed version unnecessary.”(Bolter, 2001)

Bolter claims that the hypermedia in the World Wide Web, that existed in 2001, represented a direct challenge to the printed book and that the “image will take over from the written word”. (Bolter, 2001) Hayles counters this with “the book is dead, long live the book,”(Hayles, 2005) and notes that prose is alive and well and that the new media present different but still predominately text-based opportunities for writers and artists alike. Our recent fascination with texting and blogging, both predominantly focused on text and generally, as a result of bandwidth and the requirements for speed, not heavy with images, is not part of Bolter’s vision. Ten years ago Bolter may not have seen the potential for micro-content, such as tweets to significantly reinforce the value of the alphabetic system that he claims is so artificial. (Bolter, 2001)

Why does Bolter say the alphabet, a symbol system that represents spoken language, is artificial or more artificial than computer generated visuals? In fact, Hayles refers to our traditional text form as “natural language” (Hayles, 2003) as it relates most closely to our spoken word. Both are pathways to communication and both may be open to variety in interpretation. Certainly, when possible, text is balanced with images in traditional books. Bolter rightly points out that Medieval Manuscripts, ancient Greek and Chinese art demonstrated an intertwining of text and visual but goes on to suggest that the visual became subjugated to text with the advent of printing. He says that “printing has placed the word effectively in control of the image.” (Bolter, 2001) It seems more likely that the limits of technology are the basis for this. Bolter claims that the “ideal of the printed book was and is a sequence of pages containing ordered lines of alphabetic text.” (Bolter 2001) For practical reasons, printed text has been predominantly black and white with limited illustrations and not necessarily because text is seen as superior. Bolter acknowledges that technology plays a role but insists that the printing press was a promoter of “homogeneity and reinforcing the sense of the author as authority,”(Bolter, 2001) and that text itself has been waging a struggle against the visual. Returning to Kress’s idea that we consider the wider and more complex context, it seems that this apparent conflict was due to the combined forces of the limits of technology, the political climate and the dawn of the industrial revolution.

When examining electronic picture writing, Bolter, accurately, describes how the interaction of image and text interact has changed with new technology. He allows that, historically, this “juxtaposition of word and image creates a pleasing tension” and may lead to a deeper understanding. This combination develops into layers of meaning, which Bolter acknowledges was already part of the history of the codex in the Medieval Manuscripts. (Bolter, 2001) Our concept of literacy is changing but when Bolter says that “it becomes hard to imagine how traditional prose could successfully compete with the dynamic and heterogeneous visual experience that the web now offers,” it seems he is both limiting the definition of traditional prose and disregarding the significance that the visual has always played in the history of civilization. To be sure, technology is having a great effect on the way we read and write. The audience is no longer controlled by the author and the content is controlled by the interests of the reader. (Kress, 2005) Time is altered and our sense of order has changed. (Kress, 2005) (Hayles, 2003) The text, which may consist of any combination of text, visual or code, does not necessarily exist as an artifact but as part of the process and integration of hardware and applicable software. (Hayles, 2006) Although our relationship with text will likely continue, our text will also be intermingling with computer code that ultimately links us with the machine. Hayles suggests that this intermingling of text and code may lead to a “better comprehension of our post-human condition.” (Hayles, 2003)

The English language is always evolving, the endless texts and tweets, wikis and blogs that are currently being developed, although not universally of a high literary quality, certainly do not spell the death of prose. Today’s technology users are benefiting from the quickness and ease of textual exchange used in combination with visuals as needed and possible. Today’s learners have tools that can allow a layered experience that has the potential to lead to a deeper understanding of both text and visuals. These changes do not demand the end of prose or of text, or as Bolter suggests the triumph of the visual, but are steps along the pathway of communication that we are creating, as we strive for understanding of the complex interactions of ourselves as humans, our planet and technology.

References

Bolter, Jay David. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print [2nd edition]. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hayles, Katherine. (2003). Deeper into the Machine: The Future of Electronic Literature. Culture Machine. 5. Retrieved, August 2, 2009, from http://www.culturemachine.net/index.php/cm/article/viewArticle/245/241

Katherine Hayles, “The Future of Literature,” at UBC in January 2006. Katherine Hayles – Video Stream | Audio Stream

Kress, Gunter. (2005). “Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge and learning. Computers and Composition. 22(1), 5-22. Retrieved, August 15, 2009, from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2004.12.004