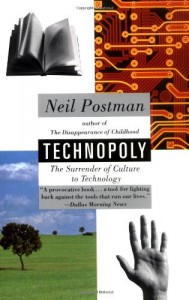

Postman (1992) begins his book, Technopoly, with The Judgment of Thamus from Plato’s Phaedrus. Thamus, an Egyptian king, judges the god Theuth’s invention of writing. Although Theuth claims that writing will improve wisdom, Thamus predicts that writing will create false wisdom. Postman builds on Thamus’ prediction by claiming that modern writing technologies, such as the Internet, have falsified the concept of wisdom by downgrading wisdom to mere knowledge and by allowing those with access to quick and convenient information the right to undeservingly consider themselves among the wise.

The Oxford English Dictionary (2010) defines wisdom as the “capacity of judging rightly in matters relating to life and conduct; soundness of judgement in the choice of means and ends; sometimes, less strictly, sound sense, especially in practical affairs: opposite to folly.” If wisdom is the ability to judge, or think critically about issues or problems and the ability to make sound decisions in real situations, then the mere receiving and memorization of information and facts is not wisdom. Remembering comparatively useless or impractical information, whether purposely or unwittingly, may actually be considered an act of folly. Thamus states that receiving information will give people the façade that they are gaining wisdom when they are in actuality only remaining ignorant (Postman, 4). Postman, who does not actually completely dismiss technology as Plato dismisses writing, elaborates by explaining that the danger of holding onto a façade of wisdom is not only that it creates factions of egotistical elites, but that those elites continue to assume more and more power as technology advances, while societies without access to information remain or are kept powerless (Postman, 9).

Because Plato was able to spread his teachings through oral means, he perhaps did not see the use in writing to teach. Plato valued the ability of the mind to remember actively, as oral cultures do. Thamus, therefore, expressed his worries to Theuth that memory would be downgraded to mere “recollection” with the introduction of writing. Through this parable of Plato’s, Postman is able to bring light to the issues concerning human dependence on technology for retaining information. An active human mind, or an active memory, is one part, or the basis of, a wise mind, therefore, artificially stored memory challenges the value of human memory. Perhaps Plato feared the invention of writing because it challenged his own regard as a wise man: “By storing knowledge outside the mind, writing and, even more, print downgrade the figures of the wise old man,” (Ong, 41). Ironically, it may be that because of the spread of writing and information, that Plato’s wise philosophies have existed to this day.

Certainly, writing technologies such as the Internet have helped speed the spread of knowledge and information. Education that does not include at least a hint of technology may be quickly and inaccurately judged as inadequate or insufficient. This is the view that Plato and Postman are warning about, that technology is bought into blindly, even by knowledgable educators, without critical evaluation. Without being instructed on what wisdom is, without learning how to apply new knowledge, there is little meaning to increasing the quantity of information one holds. In “The Balance Theory of Wisdom” in The Brain and Learning, it is argued that wisdom should be included in the school curriculum, that providing only knowledge, information and facts, is not sufficient, that in order to allow students to build better lives and a more harmonious world, wisdom is what needs to be taught (Sternberg, 2008: 141).

As technology, such as writing, makes its shifts and changes, so do the terms that are associated with those technologies, such as “memory,” “information,” even “technology” itself. Perhaps the meaning of “wisdom,” need not be regarded in the same sense it was in Plato’s day, the exercising of one’s own memory (Postman, 4) and the ability to rely on one’s own internal resources (information) instead of external resources (Postman, 12). “Wisdom,” however, ought to mean that a person is able to think critically about how new information effects how they view the world around them. In the preface of Brabazon’s (2002) book, Digital Hemlock, she states that “ignorance of history and political debate will cut the heart out of education. Without attention to social justice, critical literacy and social change, our students will know how to send an email but will have nothing to say in it.” The job of educators is not so much to impart knowledge or information and its retainment, but to ensure that students think critically about that information and find a beneficial way to apply it through discourse or practice. By doing so, educators who use writing and technological aids may be able to prove that Plato’s prediction on the invention of writing is the real falsity.

References

Brabazon, T. (2002). Digital hemlock: Internet education and the poisoning of teaching. Sydney: Griffin Press.

Ong, W. J. (2002). Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. New York: Routledge.

Postman, N. (1992). Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. New York: Vintage Books.

Sternberg, R. J. (2008). “The Balance Theory of Wisdom” in The Brain and Learning.

Wisdom (2010). In the Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved from: https://dictionary-oed-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/cgi/entry/50286109/50286109se7?query_type=word&queryword=wisdom&first=1&max_to_show=10&sort_type=alpha&result_place=2&search_id=wnWq-Xl0SEp-11059&hilite=50286109se7

Technology and Power

Commentary 1

By Melanie Wong

Technology has had a significant impact on individuals in the 21st Century. In Postman’s (1992) work he states that “once a technology is admitted, it plays out its hand; it does what it is designed to do. Our task is to understand what the design is- that is to say, when we admit a new technology to the culture, we must do so with our eyes wide open” (p. 7). It is apparent form this statement how powerful technology is. Technology provides a platform for a power struggle between the “powerless” and the “powerful.”

Postman (1992) indicates in his writing that “those who have control over the works of a particular technology accumulate power and inevitably form a kind of conspiracy against those who have no access to the specialized knowledge made available by the technology (p. 9). Technologies have provided individuals with more access to knowledge and information. In turn it has also provides individuals with more “power.” Willinsky (2003) discusses the concept of “Open Access.” It is apparent from his arguments that digital technologies have enabled the individuals with many affordances. “However, as prolific scholars…we are implicated in a secondary digital divide that is becoming all the more pressing with the spread of…technology” (Willinsky, 2003). He echoes the views that were written in Postman’s (1992) work. Although Willinsky’s arguments are centred on digital technologies, his comments regarding the “knowledge divide” are significant. It is becoming apparent that with knowledge comes privilege and power.

In Postman’s (1992) work he cites Harold Innis. In particular he indicates that “Harold Innis… repeatedly spoke of the ‘knowledge monopolies’ created by important technologies (p. 9).” Postman also mentions that there are “benefits and deficits of new technology [when] not distributed equally… [and there] are winners and losers” (p.9). Again this sense of inequality between the powerful and the powerless is expressed. Interesting when you reflect on when Postman wrote his book. It was over ten years ago that he made the comments that he did. Yet his comments are still significant and hold true at present. In many aspects being a member of a literate society, we are privileged. Our access to technologies is never an issue. We often take for granted technologies. In particular I consider digital technologies and books. In our society we have an abundance of written material and as a result an abundance of knowledge.

Ong (1982) discusses the technology of writing. Part of his argument focuses on how oral cultures are very different when compared to a literate culture. In particular he argues how oral cultures are somewhat more primitive then literate cultures. Although I have indicated in previous discussion forum postings that I don’t agree with Ong’s (1982) biased views, Ong still mentions some very valid points about the powerful and the powerless. In particular he mentions how writing has changed the human consciousness. Writing, as argued by Bolter (2001), is a technology. Ong’s (1982) takes on a semi-biased stance on literate cultures being better then oral cultures. It is my opinion that since Ong comes from a privileged position (i.e. has access to technology (writing), published a book) he is in many aspects accumulating power. Accumulation of power is when an individual has control over the works of a particular technology; this concept was expressed in Postman’s (1992) book. When we speak about technology and in particular writing, it is obvious that those who publish a book are very much in a position of power. Ong (1982) also indicates that “once a word is technologized there is no effective way to criticize what technology has done with it without the aid of the highest technology available” (p. 79). Technology is a powerful tool. Even as I write these words, I understand the significance of the power of this action.

One final point of power that was brought up in Postman’s writing was the issue of the competition between new and old technologies. He mentioned how these new technologies competed for many things (i.e. money, attention, time, prestige). It is interesting that he brings this up. Ong (1982) in his book recaps the history of writing. In particular he discusses how writing has always been considered prestigious. He provided several examples of how people who were literate in the past were in a position of power. Ong’s examples support Postman’s comments. Even now, with digital technologies or written technologies, whenever a new product is released there is a sense of competition between the old and new.

Postman’s work presented an interesting theme regarding the powerful and powerless. As an educator, I have to consider the implications of technology on my students. In particular, I have to consider the possible struggles between the powerful and powerless. In many ways, there are “knowledge monopolies” represented even in North America. Perhaps they are minor in comparison to a global scale. However, many students on a daily basis do not have access to new technologies (whether it is digital or even a book). There are certainly winners and losers as a result of this.

References

Bolter, J.D. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ong, Walter. (1982.) Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Methuen.

Postman, N. (1992). Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. New York, NY: New York

Willinsky, J. (2003). Open access: Reading (research) in the Age of Information. In C. M. Fairbanks, J. Worthy, B. Maloch, J.V. Hoffman, and D.L. Schallert, 51 st National Reading Conference Yearbook. Oak Creek, WI: National Reading Conference. Pre-print version available: http://pkp.sfu.ca/files/NRC_Galley.pdf