Audiovisual Development and Education

If a picture is worth a thousand words, what about a video? In his book Writing Space, Bolter explains that “remediation” happens when our writing space changes with the development of technology. He suggests that when we study the history of writing, we should always ask:

How does (the new) writing space refashion its predecessor?

How does it claim to improve on print’s ability to make our thoughts visible and to constitute the lines of communication for our society? (Bolter, p13)

Even though the Bolter’s argument focuses on electronic writing, I believe the same applies for audiovisual (AV) media. The development of AV started around 1930s. At the time, it provided a revolutionary way for people to communicate – our expression is no longer limited to verbal, but can also be visual (or both at the same time). With its specific affordances, how do AV media make our thoughts visible? How did they impact the way we communicate and teach? In this essay, the development of audiovisual (AV) media is revisited to explore the impact of AV on the importance of printed text and for education.

Development of Audiovisual Media

1. What is AV?

AV materials are both visual and verbal, and are available in various forms and sizes. They include film and video, which were produced by machines like film projectors, lantern slide projectors, tape recorders, television, and camcorders. This list continues to expand as people seek to communicate through multimedia.

2. Origin of AV:

The development of audiovisual media was based upon visual media. At the early stages of AV development, 52% of American schools were using visual films and 3% were using sound films according to a National Education Association (NEA) survey performed in 1933. AV development started to gain momentum after WWII. One of the reasons is that people came back from the war with first-hand experience of rapid, massive training through the use of motion pictures and other AV media. Since then, more people were receptive to the idea of learning from AV. In addition, the baby boomer generation started going to school. New schools were built with new AV equipment, and hence there was a need for technological and pedagogical support. Positions were created for building and district audiovisual coordinators. In 1947, the Department of Visual Instruction (DVI) of NEA in the United States changed its name to the Department of Audiovisual Instruction (DAVI), which developed into today’s Association for Educational Communications and Technology (AECT).

3. Mission of DAVI

In 1950, the first DVI president, Harry Wilson, stated the missions of the DAVI as follows:

|

The necessity for teaching more and more without increasing the class period, school day, or graduation age; the futility of trying to provide meaningful learning experiences without showing that which cannot be adequately expressed or understood thru words alone / the tragic neglect of the paramount responsibility for building better citizens of the nation and of the world by instilling desirable attitudes and appreciations thru the use of dramatic, emotionally derived learning—these are some of the vital problems which can be solved best, if not only, thru the use of audio-visual materials. (“AECT History.” 2010) |

It is interesting that AV was viewed as the best, or the only solution to “teaching more” and providing “meaningful learning experience” in limited time because our goals for using educational technology today is still the same. It is also interesting that Wilson pointed out the possibility to express more contents with AV, which is impossible with text alone. AV was seen as a media to complement, but not replace text.

The impact of AV on Education

The integration of AV in the field of education was made possible by the contribution of many people. They include Thomas Edison, James Finn, and Edgar Dale.

1. Thomas Edison

The great inventor of phonograph and motion picture believe that “motion picture is destined to revolutionize our educational system and that in a few years it will supplant largely, if not entirely, the use of textbooks.” (Thomas Edison, 1922)

Until now, motion pictures are often used to supplement teaching, but have not replaced textbooks. It seems like textbook is going to stay, though it might be presented in different forms to include different media. Looking into Edgar Dale’s insight provides some hints as to why this is so.

2. Edgar Dale’s Cone of Experience

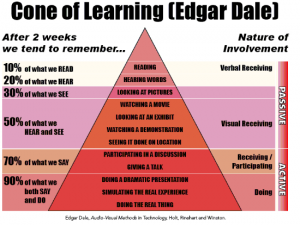

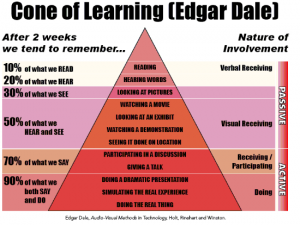

In 1946, Dale’s cone of experience was published his textbook, “AudioVisual Methods in Teaching”. The cone of experience (Fig. 1) was a tool for media selection, with in a continuum from concrete teaching techniques and instructional materials at the bottom of the cone, to the most abstract techniques at the top.

Figure 1: The original labels for Dale's ten categories are: Direct, Purposeful Experiences; Contrived Experiences; Dramatic Participation; Demonstrations; Field Trips; Exhibits; Motion Pictures; Radio; Recordings; Still Pictures; Visual Symbols; and Verbal Symbols.

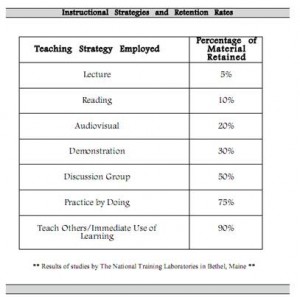

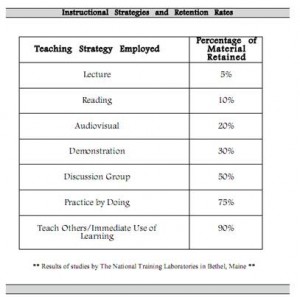

Many misconceptions arose, that the amount of content retained increases with the level of concreteness of the learning experience. This misconception was cross referenced in many papers in the discourse, as demonstrated in Figure 2 and 3.

Figure 2. Percentages were added to Dale’s Cone of Experience.

Figure 3. Instructional Strategies and Retention Rates.

Numbers were attached to the different media presented in the cone without the backup of research data. Dale clarified that there is no rank or order to the level of efficiency in communicating through media that are concrete or abstract. In fact, different media would be appropriate for specific learner and task. He acknowledged that “words can be a powerful and efficient means of conveying ideas even for the youngest children.” (Januszewski, p13)

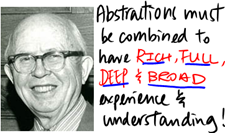

Dale believes that “we ought to use all the ways of experiencing that we can” to have rich, full, deep and broad (learning) experience and understanding.” (Januszewski, p13)

Figure 4. Edgar Dale.

Dale’s cone of experience was very influential in the field, as it was the first attempt in the discourse of the field to integrate media with learning theories.

3. James Finn

In 1963, James Finn, the president of DAVI at the time, defined “AudioVisual communication” in his article “The Changing Role of the AudioVisual Process in Education: A Definition and a Glossary of Related Terms”:

Audiovisual communication is that branch of educational theory and practice concerned primarily with the design and use of messages which control the learning process. (Robert and Ronald, p 65)

The term “messages” within this definition indicate the shift in focus away from the AV equipment (tape and films) to design of the content that is being communicated.

Conclusion

The discourse of both Finn and Dale, two influential scholars in the AV movement, agree that it is not the medium that controls the efficiency of communication, but appropriate media, or a combination of medium needs to suit particular user and content. Text has different affordances than AV media; effective communication is achieved by different media complementing, but not replacing each other.

Reference

“AECT History.” AECT. Web. 17 Nov. 2010. <http://www.aect.org/about/history/>.

“AVCR.” AECT. Web. 17 Nov. 2010. <http://www.aect.org/about/history/avcr1.htm>.

Bolter, Jay David. Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print. Mahwah (N.J.): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2001. Print.

“The Human Touch: in the Rush to Place a Computer on Every Desk, Schools Are Neglecting Intellectual Creativity and Personal.” Web. 17 Nov. 2010. <http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0MJG/is_4_4/ai_n6335687/>.

Januszewski, Alan. Educational Technology: the Development of a Concept. Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited, 2001. Print.

“Print Media Vs. Broadcast Media | EHow.com.” EHow | How To Do Just About Everything! | How To Videos & Articles. Web. 17 Nov. 2010. <http://www.ehow.com/facts_6389859_print-media-vs_-broadcast-media.html>.

Reiser, Robert A., and Donald P. Ely. “The Field of Educational Technology as Reflected through Its Definitions.” Educational Technology Research and Development V45.N3 (1997): 63-72.

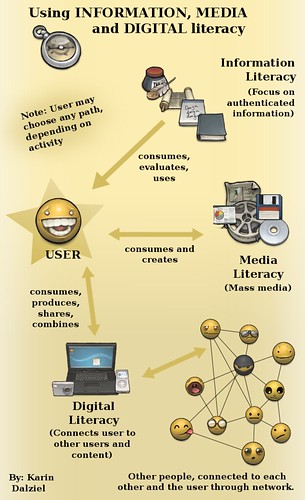

The Digital Divide

It has long been accepted that literacy is strongly connected to democratic and human rights. In the past, literacy was crucial for individuals to make educated decisions on current events, such as choosing which party was best suited to lead the nation going forward. In the modern day and age, digital media and the internet are allowing people to remain up to date on those same issues, but at a much lower cost to the environment, the producer, and the consumer.

It appears that digital media is the future of communication. Although it is likely that humanity will benefit from the great number of advantages it provides, many believe that the prevalence of digital media does not come without concern. According to Dobson and Willinsky (2009), the digital divide that currently exists is one of those concerns.

The term “digital divide” refers to the gap between those with effective access to digital information and technology, and those without such access. This gap could be due to a number of factors, such as the language, gender, or economic barriers found in computer and internet use (Dobson & Willinsky, 2009). While it is undeniable that this gap exists, the question of whether the divide is as worrisome as some believe is a more difficult one to answer.

Dobson and Willinsky (2009) state that “the pervasiveness of English on the Internet can form a… point of exclusion.” While this is true, and while by Canadian standards this might be problematic, that is not necessarily true for other cultures. In his 1998 essay “Cyberspace Is No Place for Tribalism,” Craig Howe argues that the attributes of the internet “are antithetical to the particular localities, societies, moralities, and experiences that constitute tribalism.”

Dobson and Willinsky (2009) also indicate that the ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange) was gradually superseded by the Unicode standard, “which is capable of handling the full extent of the world’s writing systems.” This was an important step toward reducing the digital divide, the results of which can be seen in the fact that Wikipedia has entries in over two hundred languages (Dobson and Willinksy, 2009).

Gender issues are also discussed by Dobson and Willinsky. They mention that in the past, computer use was much higher in males than it was in females. They go on to say that in more recent times, “males and females report relatively similar levels of use,” which is obviously not the problem. However, what is concerning is the fact that “males tend to use computers in more diverse ways, such as programming… and desktop publishing,” and that “enrolments of males and females in secondary school courses requiring sophisticated use of computers is severely skewed, with males comprising between 79% and 90% of the student population.”

While this is also true, again this may not be hugely problematic. The number of females enrolled in higher level computer classes is not nearly as important as accessibility to those classes for females. In Canada, at the very least, high schools and universities do not turn students away from classes based on gender, and it is questionable at best whether there is a social stigma attached to a female engaged in computer and technology studies. It is possible that the divide in this case is due as much to gender interest as it is to gender inequality.

Dobson and Willinsky also touch on economic factors that contribute to the digital divide, mostly in the difference between richer, more developed nations, and in less developed nations. Although I did enjoy their work, I would have been interested in seeing a closer look at the digital divide that exists in Canada.

Being a country with a very low population to land area ratio, I expected that bringing broadband internet to the entire nation would be a challenge. Marlow and McNish (2010) confirmed my suspicion. They state that “building expensive wired connections to sparsely populated rural regions [is] a multibillion dollar challenge.” They also declare that “Ottawa’s $225-million contribution to building broadband networks… is a pittance compared with the tens of billions of dollars spent on national digital programs in… the US, Britain, Australia and even such small economies as Portugal.”

Geographic location in Canada is a major source of digital divide. With dependable, high capacity fibre optic cables being very expensive, they are only available in well populated urban areas. Rural communities, which contain about 20 percent of Canadians, are restricted to satellite or wireless connections (Marlow and McNish, 2010).

This creates two problems for people living in rural areas. First, the cost is much higher. Bates (2010) reports that the average cost for satellite is $70 per month for 1 Mbps, compared to the consumer cost for fibre optic cable of $47 per month for 10 Mbps. Secondly, satellite and wireless connections are highly unreliable (Marlow and McNish, 2010). I have had my own frustrating experience with this. I live near the edge, but well within city limits of a city with a population of 85 000. My internet drops out approximately four or five times per week, at times for more than an hour, and my ISP is unable to do anything about it due to how far I live from their building. It does appear that the digital divide due to geographic location is problematic, though it is probably more of an economic concern (ie. a lack of reliable broadband makes it difficult to attract large businesses that create jobs) rather than a human rights concern (Marlow and McNish, 2010).

The digital divide clearly exists from an international level, right down to a very local level. It is most certainly a concern for many, though in some respects it seems the problem is overstated, while in others it is understated. It is worth noting that many of the “current [digital divide] concerns parallel an earlier interest in the great literacy divide between oral and literate cultures” (Dobson and Willinksy, 2009), as we can possibly compare successes and failures in efforts to reduce the literacy and the digital divide. To conclude, I’d like to include a memorable quote from Dobson and Willlinsky (2009) who make the following statement:

“The growing global dimensions of people’s participation in digital literacy… suggest that efforts to increase opportunities for access remain a worthwhile human rights goal, much as access to literacy itself has always represented.”

Resources

Bates, T. (2010). Canada`s digital divide and its implications for other countries. Retrieved Nov. 14, 2010, from http://www.tonybates.ca/2010/04/04/canadas-digital-divide-and-its-implications-for-other-countries/

Dobson, T. & Willinsky, J. (2009). Digital Literacy. The Cambridge Handbook on Literacy. Retrieved Nov. 9, 2010, from http://pkp.sfu.ca/files/Digital%20Literacy.pdf

Howe, C. (1998). Cyberspace Is No Place for Tribalism. Wicazo SA Review.

Marlow, I. & McNish, J. (2010, April 2). Canada`s Digital Divide. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved Nov. 14, 2010, from http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/canadas-digital-divide/article1521631/

Sciadas, G. (2001). The Digital Divide In Canada. Science, Innovation, and Electronic Information Division; Statistics Canada. Retrieved Nov. 14, 2010, from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/56f0009x/56f0009x2002001-eng.pdf