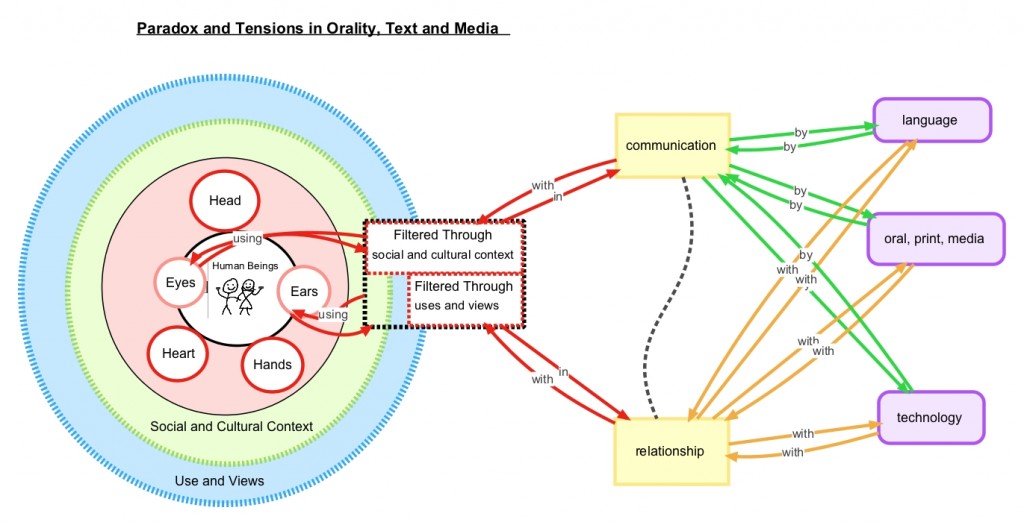

The introduction of new technologies within a society often results in a critique of how such innovations will affect human consciousness. Plato argues how the technology of writing influences one’s memory, does not represent reality, and ultimately weakens the mind. Such arguments are presented in The Seventh Letter and Phaedrus which in turn, ironically, are recorded by way of text.

“The specific [writing] which you have discovered is an aid not to memory, but to reminiscence, and you give your disciples not truth, but only the resemblance of truth; they will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing; they will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing; they will be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without the reality.” (Plato, n.d.)

Unlike Plato, Ong (1982) seems to make a similar argument in his text; complicating our thoughts on the written word. My understanding is that Ong believes print and writing isolates humans from one another creating multiple perspectives that do not resemble the truth. I disagree with Ong, but I am slightly cautious because I have never experienced a predominantly oral culture. I try to imagine if oral culture is more united and truthful than print culture, but I instantly begin to wonder if both cultures demonstrate complexities because human beings themselves seem to complicate language, stories and texts; despite being oral or print based. If we take children for example before they are able to read or write, their oral stories are imaginative and creative and most importantly never are told the same way each time, consistently details change. This theory can be applied to all human beings; language changes in all capacities oral or print—I do not believe one is any better than the other or more authentic.

I do believe print has the potential to isolate; however not always. Print has created unity especially among groups in our postmodern world. For example if we take a group from a grade 10 class and ask them to read a text—the group than has a common thread to discuss, work through, connect and expand on. The students who do not read the text and instead stare out the window become isolated from the group losing the only thread that connects each individual in the room to form the group. Human society may have once been unified by oral culture, but nothing concerning contemporary society is unified or open. We are a culture of individuality—this may have been brought about by way of technology innovations, but I am really not convinced. However Ong seems very convicted, “The spoken word forms human beings into close-knit groups. When a speaker is addressing an audience, the members of the audience normally become a unity, with themselves and with the speaker. If the speaker asks the audience to read a handout provided for them, as each reader enters into his or her private reading world, the unity of the audience is shattered, to be re-established only when oral speech begins again. Writing and print isolate.” (Ong, 1982, p.73) I believe that we have moved very far away from a unified model.

It is important to reflect on the influence of today’s technological innovations on the 21century learner. Like those who were raised in a literate culture find it difficult to fully understand the influence of writing and text on an oral culture, I believe that some will find it difficult to comprehend the full effects of today’s technologies on human consciousness. Today’s learner has been raised in a society whereby the World Wide Web has been commonplace, a great number of North American households have multiple cell phones, and social networking is perhaps the most prevalent communication means among teens and young adults. Oral communication by way of face-to-face interaction is diminishing. How will such tools affect human consciousness? Will these tools “enrich the human psyche, enlarge the human spirit, and intensify its interior life”? (Ong, 1982, pg. 82). Will such innovations lead to a greater degree of human isolation?

References

Ong, W. J. (1982) Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. New York, NY: Routledge.

Danielle’s Ong Commentary

I have chosen to write a commentary on Ong’s (1982) fourth chapter entitled Writing Restructures Consciousness because I am finding the history of writing fascinating and I wanted to explore the questions surrounding the human motivation to write as well as our motivation to create new technologies.

Ong briefly illustrates the history of writing and how this amazing technological innovation transformed and heightened human consciousness. This was a particularly eye-opening history lesson for me. I have often thought of writing as a technology but I have not considered how, unlike speech, writing is artificial – that it is governed by consciously contrived, artificial rules. While I agree with this to some extent, I would not go so far as to call it artificial. It is perhaps an extension of ourselves – a reproduction of our thoughts or speech. It could therefore be argued that speech is not truly speech unless it is heard. In the same way, writing is not truly writing unless it is seen (or touched in the case of Braille). Those who see Ong as a technological determinist would likely agree that writing is not an independent, self-controlling force that is completely removed from who we are as human beings. As Chandler (1995) points out, technology is shaped by society and “is subject to human control” (para . 29).

Ong also goes on to further define writing and differentiates very early writing with mere pictures or memory aids that do not in any way represent words through a code system. When a code or set of conventions is applied to a picture or memory aid (in order to represent the exact words the writer intends to convey to a reader), it becomes writing (Ong, 1982). This particular discussion once again raises the point that writing is only writing if it is seen by others. I think this point further illustrates the social nature of language. Codes and conventions need to be known to the reader in order for their particular writing sample to be considered writing. When the writer is not the reader, these codes and conventions are imperative. While I agree with Ong that a script is more than a mere memory aid, I would disagree that the memory aids exemplified here including drawings, notches on a stick or suspended cords do not constitute writing if only decipherable to a select number of people or the writer alone. Though these examples are far from those found in high literacy, and though language is meant to take place in a social context, namely as communication, I feel that writing as a language decipherable even to the writer alone should still be considered writing.

In Ong’s discussion of memory and written records, he illustrates how writing did not always inspire trust. Those who were able to give verbal accounts of an event were considered more reliable than a written account of the same event. Ong points out that in writing’s early days, texts could not be disputed. Only those present and able to verbally refute or prove a statement were considered trustworthy. What is particularly interesting is how witness testimony has evolved with the onset of literacy. Ong points out that thinking through one’s thoughts promotes dictation and while those thoughts may appear in writing as they would in a verbal testimony, they are deemed unreliable. In comparing our present situation with the oral cultures of the past, it is clear to see how the invention of writing and spread of literacy has in fact diminished our memories as Ong mentions earlier. It has not only diminished our memories but our confidence in the spoken word to the point where we do not trust what is said unless we “see it in writing”.

Ong has aptly exemplified at various points throughout his book that writing has diminished our memory capabilities. I think that this is part of the reason why many find writing to be an agonizing process. Ong mentions the agonizing process of writing enough times to make one think that he in fact shares this opinion, though I find reading his work to be the complete opposite of agonizing. He illustrates the roles that writers must design for their readers. He also mentions the important need to be clear and unambiguous to the point where the reader can see and hear what has been written. Creating an image or a sound through text is indeed agonizing when it is much more easily said or demonstrated in an oral context. Writing is a painstaking process where the writer must account for every detail of each word. Such exquisite circumspection, as Ong (1982, p.103) puts it, is the very reason that the book is often better than the movie.

References

Chandler, D. (1995). Technological or media determinism [Online]. Retrieved from http://www.bos.org.rs/cepit/idrustvo/st/TechorMediaDeterminism

Ong, W. (1982). Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London:Methuen.