Posts from — November 2009

RipMixFeed – my blog

Please visit my blog when you get a chance. I started it around the same time I started this course and the MET program. It’s been my place to experiment with different software and understand the world of blogging. I don’t blog frequently enough but that may change over time. What I particularly like is having links to other blogs or sites that are important to me.

I guess what I find hardest about blogging is trying to keep a balance between my private and professional self. I want to give my colleagues a glimpse of my interests and skills but I don’t want to share myself with the world. Hopefully you will discover me a little bit at cteachr.wordpress.com

November 11, 2009 2 Comments

RipMixFeed Explanation

My Toondoo is on the King-Byng crisis of 1926. It was the last time the Govenor General was able to control the affairs of Canada. Prime Minster Mackenzie King wanted to dissolve parliament and call a new election due to the fact that his cabinet had done some less than reputable things. By calling an election, King was hoping he would aviod a vote of non-confidence which he was surely loose. However, when King asked to dissolve parliament the Govenor General, Lord Byng of Vimy said no due to the fact that he thought King was not owning up to his responsiblities. King, outraged, resigned on the spot which brought in the leader of the opposition, Aurthur Meighen into power. What is ironic, is that Meighen then asked Byng to dissolve parliament which Byng granted. King was able to twist the story to make it look as though Byng and Meighen had a plot to overthrow him! In the election King won by a landslide and gained a majority. This is a significant moment in Canadian history because it was the last time the Governor General was able to override the Canadian elected officials (the PM).

I had so much fun making this toondoo! I am going to use them with my classes for sure. It is a great way to represent material in a visual format. Also, I find it interesting that my cartoon conveys the same material that I wrote above. A fantasic site as well!

If you haven’t checked it out yet, Toondoo even has political figures such as Obama, Clinton etc. They even have superstars like Michael Jackson! I chose to make my own characters by uploading a picture of the real characters and then make my cartoon version based on the picture.

A great resource!

November 11, 2009 No Comments

RipMixFeed – My ToonDoo!

November 11, 2009 No Comments

Commentary 2: Hypertext

In Chapter 3: Hypertext and the Remediation of Print in the book Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print, Jay Bolter examines hypertext. In the introduction to the chapter, he states how common hypertext has become and that it provides beneficial links to other information (Bolter, 2001, p.27). He compares hypertext to a footnote in a book and says that it is the electronic equivalent of a footnote, except that hypertext can point to a page that has additional hypertext links that point to additional pages that are not necessarily less important (Bolter, 2001, p.27). He states that the role of hypertext is to provide a transparent structure to a website, provide footnote-like information, and define relationships (Bolter, 2001, p.27). He also describes the role of writers who use hypertext: “The principle task of authors of hypertextual fiction on the Web or in stand-alone form is to use links to define relationships among textual elements, and these links constitute the rhetoric of the hypertext” (Bolter, 2001, p.28-29).

The author has subdivided the chapter into the following sections:

· Word Processing and Topical Writing

· Hypertext

· Writing as Construction

· Global Hypertext

· Hypertext as Remediation

· The Old and New Hypertext

In Word Processing and Topical Writing, Bolter (2001) describes word-processing with a computer as being a dynamic and flexible way to work because documents can easily be edited (p.29). He states that when word processing, writers think and write about topics “whose meaning transcends their constituent words” (Bolter, 2001, p.29). Also through word processing, you can set up complex hierarchies of many topics in a tree-like structure which is a manageable way to work because word processing enables users to move, delete and add information with ease, unlike a typewriter, where more than one hierarchy is difficult to manage (Bolter, 2001, p.32).

In Hypertext, Bolter (2001) describes the process of writing on a computer called prewriting in which students create a “network of elements” (p.33) that can be easily edited, moved around, and removed (p.33). Prior to writing with a computer, the writing process was linear (Bolter, 2001, p.33). Bolter (2001) describes the electronic connections that hypertext affords its readers compared to having to use an index or page numbers in printed books (p.35). He also describes electronic writing as being topographic whereby writers organize their text into units of information that are linked to a “textual structure spatially as well as verbally” (Bolter, 2001, p.36).

In Writing as Construction, Bolter (2001) describes writing with a computer as being both inclusive because it is “open to multiple systems of representation” (p.36) and constructive because “an electronic writer can build new elements from traditional ones” (p.37).

In Global Hypertext, Bolter (2001) defines hypertext as “the dynamic interconnection of a set of symbolic elements” (p.38). He states that it’s the melding of both computer programming and writing that creates hypertext whereby writers write within data structures (Bolter, 2001, p.38).

In Hypertext as Remediation, Bolter (2001) states that hypertext would not exist without digital technology and that it is the “remediation of print” (p.42) because it is an improvement to printed text, which is linear and static (p.42). He states that hypertext is more representative of how people think because people think by making associations, not in a linear manner (p.42). As a result, the use of hypertext allows us to “write as we think” (Bolter, p.42).

In the Old and the New Hypertext, Bolter (2001) describes hypertext as a type of writing that has made a break from the past with printed writing (p.44). It is characterized by “interactivity and the unification of text and graphics for achieving an authentic experience for its reader” (Bolter, 2001, p.45). Bolter (2001) describes the dependency that hypertext has on print: “print forms the tradition on which electronic writing depends, and electronic writing is that which goes beyond print” (p.46). This dependency is reminiscent of “the age of Secondary Orality” (Ong, 1982, p.3) meaning that electronic technology such as hypertext “depends on writing and print for its existence” (Ong, 1982, p.3).

Throughout the chapter, Bolter (2001) describes hypertext as being a positive invention due to the fact that word processing and the creation of hypertext links have made the processes of writing and reading easier. However, DeStefano and LeFevre (2005) state that hypertext links impair reading performance due to the fact that it makes it more demanding for people to make decisions and process graphics while reading (p.1636).

Bolter (2001) also provides a positive account on the linking capability of hypertext links: being able to link to additional information. Horton (2006) concurs that people are accustomed today to being able to quickly read through online text by using hypertext links to navigate through an online document and link to relevant information inside or outside an online document (p. 534-535). Horton (2006) recommends the use of hypertext links when designing eLearning courses because hypertext links make it easier for learners to access and read about topics related to the course content (p.305). Horton (2006) suggests that hypertext links be used to cross-reference reference information, background theoretical information, exceptions to rules, procedures, definitions, and prerequisite information (p. 305-306).

However, Clark and Mayer (2008) recommend that hypertext links be used sparingly when designing an eLearning course because if they are used too much, they can have a negative impact on the learner’s ability to learn (p.308). They recommend that hypertext links not be used for core course information and that they be used for information that is peripheral to the course as many learners will skip the linked information (Clark and Mayer, 2008, p.308). In addition, Driscoll (2000) also cautions against the use of hypertext links in instruction because they can distract the learner by removing them from where they are currently learning and sending them off in different directions (p.161-162).

Conclusion

The invention of hypertext has revolutionised the way in which people write and read electronic documents and learn. Bolter (2001) describes the many qualities that hypertext has brought to us including: ease of writing, ease of linking to additional information, ease of navigating, and ease of reading. In addition, hypertext links can be a wonderful resource when designing an eLearning course. However, they need to be used with caution: only when necessary and not for essential core course content as they can distract the learner.

References

Bolter, J. (2001). Writing spaces: computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Eribaum.

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2008). e-Learning and the Science of Instruction: Pfeiffer San Francisco.

DeStefano, D. & LeFevre, J. (2007). Cognitive Load in hypertext Reading: A review. Computers in Human Behaviour, 23, 1616-1641.

Driscoll, M.P. (2000). Psychology of Learning for Instruction. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Horton, W (2006) E-Learning by Design, John Willey & Sons, Inc.

Ong, Walter (1982). Orality and literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London: Methuen.

November 11, 2009 1 Comment

An overview of a remediation: From Scroll to Codex

An overview of a Remediation: From Scroll to Codex

Introduction:

Writing as a mode or method of human communication, has been in existence for a very long time and has been continuously evolving, progressing, regressing, moving forward, and changing (Botero et al 2000). These processes of change, these transitions or remediations of ways of writing, reading and of knowing are shaped by and acted upon complex socio/political and historical/cultural forces that continue to inform our ways of communicating today, at the cusp of the twenty first century (Bolter 2001).

A brief overview of the trajectory of a specific remediation, that of the transition from the primacy of the use of the Scroll as a way of storing and communicating written text and knowledge into that of the Codex will be the focus of the discussion to follow. Remediation here will specifically refer to the movement from one media or mode of written communication to another as described in Jay Bolter’s work about writing in the context of the advent of computers (Bolter, 2001). It should be noted that the outline of the cultural and political forces at play is limited here not only to a specific western and Eurocentric context but also to a specific chronological period or range, with a primary focus on the late Roman period extending to about the third century AD. This particular remediation traces a fascinating and complex path, weaving a trajectory through great cultural and historical shifts that occurred over a period of several hundred years.

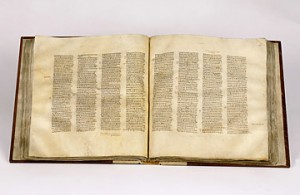

Scroll to Codex: One of the First Bibles [1]

Scroll to Codex: One of the First Bibles [1]

Writing in its many forms has always communicated the literal content of the text, however, the information contained within the text and the way and the format in which it is presented communicates much more (Edney, 1992). The Scroll and the Codex “speak” of or describe the extant power relations of the historical moment, and in many ways also of the specific culture from which it emerged. Writing delineates and reflects specific epistemological systems and communicates what a specific culture considered important enough to be considered Knowledge (Mokyr, 2002).

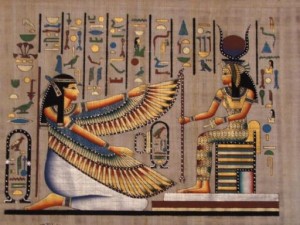

Moreover, the act and process of writing is not a neutral one; nor are compilations of writing, whether contained in Scroll or books, neutral artifacts. Where ever writing appears and in whatever technological form it manifests, it bears the very specific imprint of the cultural, political and economic influences that shaped and created it (Bolton ibid). This holds true for all forms of writing over the vast expanses of recorded history as they are all grounded in the specifics of their unique cultural and historical milieu. From the ancient hieroglyphics of Egyptian dynasties, to the letters on the papyrus Scrolls of the ancient Greeks or the illuminated manuscripts of medieval Europe, from the printed pages of industrial era texts to the digital traces of keystrokes in the email communications of modern societies; all reveal and reflect the culture and the power relations within that specific historical moment or epoch.

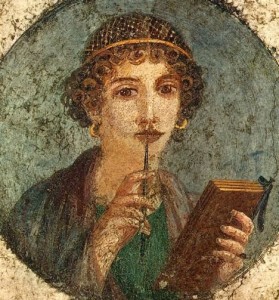

The act of Writing: framed by culture and by history [2]

This discussion will demonstrate that the remediation of writing on the Scroll as it reconfigured and resituated itself into the technology of the Codex was enabled by a unique set of cultural forces, and was framed by the socio-economic and political power relations of a specific historical context.

A brief introduction to the terminology used here and the historical and cultural contextual backdrop to this transition will begin the discussion, and an examination of the changes that occurred to transform the Scroll into the Codex will follow.

Terminology:

Remediation as used by Bolter is a process, it describes the transition from one media or mode to another, it is dynamic [not static] it has the potential to be and frequently is, evolutionary, but not necessarily logically progressive. It is a series of changes, but they are not simple or linear trajectories of change. The process of remediation may involve simultaneous progression and digression, and tangential leaps forward followed by regressive movements away from positive innovation. All of these changes involve a myriad of forces and or characteristics having nothing inherently to do with the actual media or medium itself (Bolton ibid). To sum up, the process of remediation of modes of communication is as complex as the historical and cultural forces that shaped those changes.

An example of Graffiti: late twentieth century writing [3]

An example of Graffiti: late twentieth century writing [3]

A similar qualification must be placed upon the meaning of Codex. Although it evolved over time to have a specific meaning within legal contexts, in our examination here the term Codex will denote leaves of wood, papyrus, and more frequently, to parchment, bound together into the form of a modern volume, or what is commonly referred to as a book.

When referring to the term Scroll we are going to define it for the purpose of our discussion here as very simply a roll of paper [originally papyrus] or of parchment, usually, having writing on it.

The Process of the Remediation of Writing:

The remediation of writing is complicated because the process is not only driven by functional or rational requirements, that is, it is not just a series of what could be evolutionary or progressive innovations or improvements to a particular medium [employed as communication device] over time. Nor according to Bolton, is there a clear division or cut off between the use of one medium to the other.

Writing is Knowledge & Knowledge is Power:

Throughout history the use, access to and control of modes of writing, has been recognized by all cultures, as was noted above, not just for its inherent importance as a way of communicating, but also as an effective way of demonstrating and communicating power. Therefore, what is conveyed within a specific scroll or codex [or book] has always been something more than just its literal, surface or even just its cultural meanings. Writing and the information a civilization formulates into knowledge, as it manifests and is contained in scrolls and in books, issues out of a complex mixture of cultural and historical forces that frame and represent specific ways of perceiving and of interacting with the world (Lunsford 2006). These cultural and historical forces fuse with ways of knowing [systems of knowledge and knowledge acquisition or learning] that are specific to each unique context. All cultures in the western context from the very earliest of times, seem to have shared a recognition that being able to control the distribution, the storage and the access to knowledge [including what is left in and what is excluded from that corpus] that is incorporated within written texts, is both central to the control of societies [and its people] and is a secure gateway to power (Mokyr, 2002). Knowledge, so they say, is power.

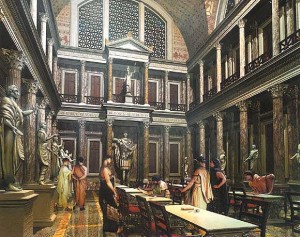

Ancient Greek Library: Artists rendition [4]

Ancient Greek Library: Artists rendition [4]

Writing, as a mode of communication, has been a hallmark of human civilization since the beginning of what has become know as history. History as a compilation of the writing of those who were in power, tracks a series of social, cultural and political transitions, involving the rise and fall of human cultures and civilizations over time as seen through the lens of those political and historical power structures and institutions. Many of the same forces [power dynamics, economics, regional and geographical realities] that shaped these historical shifts also determined the shape of the transition from Scroll to Codex.

The Primacy of The Scroll:

An ancient writing technology evolves and then fades away

The Scroll in its many forms, was used over a period of over three thousand years and as a writing and communication device, was the first record keeping technology that allowed changes, revisions and/or edits to be made. Early scrolls were developed using papyrus, a reed native to ancient Egypt, found in abundance along the banks of the Nile River and in marshes throughout the region. The Egyptians perfected the use of papyrus and developed procedures and instructions on how to best prepare it. In an elaborate process, the reeds of the papyrus plant were cut, peeled, moistened and pounded out into layers. The layers were pressed together to form sheets, left to dry and then finished, by rubbing with stones or shells, into a smooth surface suitable for writing on (Szirmai, 1990).

An example of ancient Egyptian {light} papyrus [5]

An example of ancient Egyptian {light} papyrus [5]

A significant and early form of the scroll was the ancient Hebrew text contained within the Torah [3300 BCE]. However, traditionally the use of animal skins, treated in special ways, was employed for the surface of the “page” or viewing area of the Torah. The history of the Torah Scroll, along with its many fascinating and elaborate traditions [in terms of transcription practices and protocols] is a bit of an anomalie, in terms of forms of writing in the Scroll format.

The Torah Scroll [6]

The Torah Scroll [6]

The papyrus scroll was much more common. It was developed chiefly in its early forms by the Egyptians, then modified also by the Greeks and further developed later by the Romans. Over time it became more & more refined and somewhat more practical in its applications.

Papyrus Scrolls: the medium of choice for centuries

The inherent features or characteristics of papyrus determined certain features of the Scroll. For example, only specific areas of the plant could be used for the creation of papyrus, and the size of the both the width of the scroll and its length was limited. That is, beyond certain parameters the papyrus page would simply fall apart and of course there were limits to how big a scroll could be, just as there were very real limits to how much text could be viewed at one time, as it was unrolled for reading (Szirmai, 1990).

Early Greeks like the Egyptians, recognized how important the control and storage of knowledge was to the success of an empire. Unfortunately, many of the great libraries, such as those of the Babylonians and of the early Greeks, are known to us only through descriptions of their grandeur in the writings of ancient scholars. Much as been said for example, of the great scroll based libraries of ancient cultures, such as those of Solomon and of Alexandria (Gibbons, 1877). Early recognition of the esteem in which these receptacles of knowledge were held, is reflected in the prestige which attached to the leaders who deliberately acquired them in their conquests, and to the grand and impressive architecture that was created to house them.

A monument to Roman Knowledge & History:

A monument to Roman Knowledge & History:

Interior of Trajan Library Artist Concept [circa 53 -177 a.d] [7]

Roman Ingenuity improves the Scroll:

By the time that the Scroll was being used by the Romans, many auxiliary technologies for the viewing and storage of the scroll had evolved. Special tables and podiums were developed which allowed for maximum viewing of areas of the scroll, and for reading and for writing on the scroll, which improved the efficiency and practicality of their use (Szirmai, 1990).

Eventually, Roman scholars and officials specified optimum measurements for scrolls, standardized its manufacture and developed guidelines for its overall appearance. Best practices included standards for width, length, colour and smoothness as well as the overall appearance of top quality scrolls. It should be noted that papyrus, throughout its time as the most favored writing medium, was always an expensive item. Writing, reading, having access to knowledge and to the materials required for writing, was the privilege only of the elite ruling classes, and was never something that the average citizen would have had access to (Roberts, C.H., 1984).

The Message is the Problem: Inherent flaws in the Medium

Part of the remediation of the scroll to codex involved the recognition by the Romans in particular, as the last great cultural inheritors of the Scroll, of some of the difficulties inherent in the medium, even with all of the accommodations, [such as special tables and podiums] that had been made. These problems including that it was difficult to move forward or backward within the scroll itself. In fact, there were many cases where this difficulty resulted in mistakes by scribes [those responsible for copying texts] who either accidentally missed sections of text [fragmentation of texts] or who unnecessarily repeated sections of text [because the section already recorded was not easily viewed].

Storage and Transport of Scrolls:

Storage of scrolls was always challenging, as noted above, it was limited by the strength of the papyrus, which delineated the maximum length of the scroll. It was a fragile medium at best, even when it was reinforced. Sticks, rods, or rollers made of wood or of ivory were inserted within the scroll to try and reinforce and support them but scrolls were always in danger of collapsing altogether or of bending and cracking in the middle (Roberts, 1984).

Papyrus scrolls could be damaged quite easily by moisture and needed special containers for both storage and transport. Sheets of papyrus that were pounded together [known as rolls, within the larger scroll] taken together, could not exceed a specific size, the maximum length was about 15 feet. It was the parameters of the technology, in terms of the maximum length for the document itself and the size and quantity of the sheets or rolls of papyrus within the Scroll that determined both how long a document it could be, and determined how it could be divided into segments or sections.

Early Greek Scroll showing wooden rolling sticks [8]

Early Greek Scroll showing wooden rolling sticks [8]

Sections or partitions of works contained within scrolls were very much defined by the medium, just as manuscripts at a later time were influenced by the format of books. These sections or partitions gradually transformed, eventually forming the familiar sections or chapters, of the codex or book. These parameters determined also the amount of viewing and writing “space” [known as the paginae, later to become the page] and the amount of text that could be communicated within the viewing area [estimated at between twenty and fifty lines] (Roberts, 1984). These characteristics became standardized features so that the work involved in unrolling and re-rolling the scroll was kept to a minimum. Even so, reading and writing using scrolls, was a fairly labour intensive activity and every time the scroll was manipulated it was at risk of being damaged.

Shelving with holes in it [like the cubbyholes of a post office] was used for the storage of scrolls, but when several scrolls collected together were required [like the chapters or sections of one book] a container called a book box was employed to store the work. Marking, labeling and storing of libraries filled with scrolls was very difficult and again the limitations of the medium itself determined how many scrolls could be contained together and how they were stored.

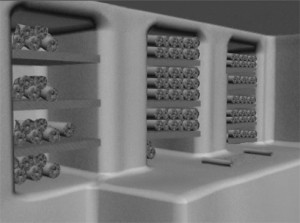

Scroll Library of Qumran:

Scroll Library of Qumran:

Reconstruction of Qumran’s Library (illustration S. Pfann, Jr.) [9]

Pens filled with ink, were the mostly common implements used for writing on papyrus. Early pens were fashioned out of a variety of materials. Some pens were made from reeds, some were carved out of wood, and some were formed from bronze or of copper sheets that were shaped into vessels that were filled with ink. Ink was made from a variety of substances, such as ash or soot, the ink from cuttlefish or octopus, or from resin, sometimes the residue of wine [the proverbial dregs] was used for ink also (Lunsford, 2006).

A temporary alternative leads the way to a permanent solution: The Tabula Cerata

Although papyrus scrolls were expensive, difficult to edit and challenging to store and transport, fortunately, there was always, a less expensive alternative. In tandem with the advent of the scroll an auxiliary technology for short term and unofficial or casual and temporary, communication needs was used. Even during the time of the primacy of the scroll, the use of the Tabula Cerata [or the wooden writing tablet] was the medium of choice for many, such as students practicing their writing skills, for business people and merchants who had quick and frequently cryptic information to impart, and for unofficial internal government communications. These tablets usually had two leaves [two was the most common number of leaves but there could be as many as four to an upper limit of ten] which were thin pieces of birch or alder, treated with a surface of smoothed out wax that could be written or inscribed on, with a metal stylus or pen (Szirmai, 1990).

An example of the Tabula Cerata shown with stylus or wooden pen [10]

An example of the Tabula Cerata shown with stylus or wooden pen [10]

Roman Necessity as a Driver of Innovation:

As mentioned above the use of papyrus reigned supreme for a very long time, with the notable exception of the Hebrew tradition [and the production of the Torah in particular] that employed the use of parchment of made from animal skins. However, a set of circumstances caused a break in the flow of the distribution of papyrus and the resulting temporary shortage of the material in tandem with modifications to the wooden writing tablet, congealed to create an innovation, a shift, a remediation that laid the way for the final transformation of the Scroll into the Codex.

There is some controversy as to when and why there was a shortage of papyrus supplies, but there is consensus that it was the temporary inability of the Romans to import papyrus that forced a search for alternatives and resulted in the first real transition from the use of the scroll to that of the earliest forms of the Codex (Szirmai, 1990). The refinement of the early Tabula Cerata was among the many inventions and innovations of Roman culture. Parchment began to replace the more cumbersome wooden sheaves or leaves of the wooden tablet. Because of their pliability and because the leaves were so much thinner, the amount of sheets that could be contained, immediately increased, moving from [as above] the usual two, to as many as sixteen to pages within one tablet or book. It was the flexibility of the parchment that made the difference; it could be folded or bent without breaking or falling apart.

From Scroll to Tablet: From Tablet to Codex:

The early uses of these tablets remained chiefly for temporary or business communications that were brief and/or repetitive, so the early codex was used chiefly for records of business transactions and for brief official communications and letters. However, the scholars and writers of the first century soon adapted the technology, and over the first few centuries it became more and more common (Roberts, 1984). The traditional wooden tablet was transformed into a tablet with parchment leaves and then finally into a collection of leaves bound together [originally sewn together] which began to resemble the modern book.

Roman Mural: Keeping Track of the Harvest: early uses for the cerata [11]

Roman Mural: Keeping Track of the Harvest: early uses for the cerata [11]

The final remediation [which never completely eliminated the use of the scroll], was the result of more than just shortages of materials or even practical considerations of which medium would be easier to use and to store. As has been indicated in many works, (Lunsford 2006) (Roberts 1984) (Szirmai, 1990), it was the early Christian church that completed the remediation of the scroll into the Codex. Not only was the church interested in establishing the primacy of a specific work [what later became known as “The Bible”], they were also very concerned with distinguishing themselves from other religions and from those in power, specifically the Romans.

The practical aspects of the decision to adopt the codex was also relevant, that is, the entire work known as the Gospels, was more readily packaged in the form of the codex. At the dawn of the new millennia this format was critical to the early dissemination of the first versions of the bible at a time when the church was actively promoting itself across Europe and was not yet in a position of power.

Finally, it was not only important to the early church that they distinguish themselves from the Romans with their pagan traditions but it was also important to them to demonstrate that they were different from the Hebrew religion and its scroll based traditions [as noted above].

Gutenberg Bible: later version of the ever evolving Book [12]

To sum up, the remediation of the scroll to the codex, occurred in tandem with the growing dominance of the Christian faith, which had established itself as a major force by the end of the fourth century [Gibbons, 1877). Writing, as a mode of communication, has been a hallmark of human civilization since the beginning of what has become know as history. History as a compilation of Writing, tracks a series of social, cultural and political transitions, involving the rise and fall of human cultures and civilizations over time through the lens of the dominant political and historical power structures and institutions.

Many of the same forces that shaped these historical shifts also determined the shape of the transition from Scroll to Codex. However, as has been shown, the remediation of this format for communication, was not straight forward and in the end was pushed not just by practical, economic or political forces alone, but also and importantly, in this instance, by the perceived needs of an emerging religion, that was soon to become a dominant force in the history of western culture.

References:

Bolter, J.D.(2001)Writing Space: Computers, hypertext, and the Remediation of Print

Lawrence, Erlbaum Associtates Inc. Mahwah, NJ, USA

Bottero, J., Herrenschmidt, C., & Vernant, J. P. (2000). Ancestor of the West: Writing, reasoning, and religion in Mesopotamia, Elam, and Greece.

Edney, M. H. (1992). Mapping the early modern state: The intellectual nexus of late Tudor and early Stuart cartography.

ETEC 540: Module 4:Literacy and the New Media

Digital Literacy and Multiliteracies

Habermas, J. (1986) Knowledge and Human Interests Cambridge, Polity Press

Lunsford, A. A. (2006). Writing Technologies and the Fifth Canon. Computers and Composition. 23, 169–177.

Mokyr, J. (2002). The Gifts of Athena: Historical Origins of the Knowledge Economy.

Roberts, C.H. (1984) The Birth of the Codex

Oxford University Press, USA

Digital References:

Szirmai, J.A. (1990) Wooden Writing Tablets and the Birth of the Codex

Gazette du Livre Medevale, No. 17

Also: retrieved online October 2009

http://cool.conservation-us.org/byorg/abbey/an/an15/an15-4/an15-407.html

Classic Encyclopedia Online (2006) 11th Edition, Encyclopedia Britannica

http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Later_Roman_Empire

Reference: Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1877)

The British Museum Online: What is Writing?

http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/themes/writing/what_is_writing.aspx

Retrieved online: October 2009

The Israel Museum, Jerusalem: A Wandering Bible: The Aleppo codex

http://www.english.imjnet.org.il/HTMLs/article_453.aspx?c0=13815&bsp=13246

Retrieved online: October 2009

List of Digital Visual References: All images from Google Images

Retrieved: October 2009

[1] First Bible: one of the earliest versions of the Bible

[2] The Act of Writing: Artist’s conception

[3] Graffiti: Late twentieth century writing

[4] Ancient Greek Library: Artists rendition

[5] Early Egyptian Papyrus: {light type} Google Images

[6] Torah Scroll: one of the earliest parchment scrolls

[7] Trajan Library: A monument to Roman History: circa 53 – 177 a.d

[8] Early Greek Scroll: showing wooden rolling sticks

[9] Scroll Library of Qumran:

Reconstruction of Qumran’s Library (illustration S. Pfann, Jr.)

[10] Tabula Cerata: Example showing wooden stylus or pen

[11] Roman Mural fragment:

Keeping Track of the Harvest: early use of the Tabula Cervata

[12] Gutenberg Bible: example of the evolution of the Book

November 10, 2009 1 Comment

PBS:Digital Nation

I found an interesting transcript of an interview involving Mark Prensky and Mark Bauerlein on the topic of education and technology. The interview took place on June 25, 2009 and is posted on PBS’ Frontline: Digital Nation link. It’s interesting beyond the topic (respecting youth culture, gaming to learn, integrating ed-tech) and on the level of “why isn’t this a sound file”? Something to ponder!

Click to PBS Frontline: Digital Nation

November 10, 2009 2 Comments

Altered Tales: Fairy Tales through Oral, Literary and Cinematographic Traditions

–Wiki research Project by Caroline Faber–

Follow the link below for a brief overview of the adaptations of fairy tales over time and in the face of technologies of orality, print, and cinema.

November 9, 2009 2 Comments

How word processors and beyond may be changing literacy

Commentary #2

The word processor, in combination with the computer disk and CRT monitor, was first introduced in 1977 (Kunde, 1986). As Bolter points out “the word processor is not so much a tool for writing, as it is a tool for typography (p. 9).” It seems that, even today, the word processor is essentially used as a tool to mimic conventional methods of typing. Whereas older printing processes lock “the type in an absolutely rigid position in the chase, locking the chase firmly onto a press,” a word processor only differs in that it composes text “on a computer terminal” in “electronic patterns (letters) previously programmed into the computer (Ong, p. 119).” Bolter notes this by stating “most writers have enthusiastically accepted the word processor precisely because it does not challenge their conventional notion of writing. The word processor is an aid for making perfect printed copy: the goal is still ink on paper (p. 9).” The word processor helps better facilitate the processes that were once done on the typewriter. That is, writers still type in text letter by letter, but the computer greatly improves revision. A few of these improvements include copying/cutting and paste, changing fonts and paper size, and inserting automatically updating table of contents, outlines, references. It is “in using these facilities, the writer is thinking and writing in terms of verbal units or topics, whose meaning transcends their constituent words (Bolter, p. 29).” In this regard, the word processor did not change the printed word. However, although the word processor did not fundamentally change how a printed product looks, it did have a major impact on industry and business and on literacy in education.

In the early 1980s there was much focus on the difference word processors were making in industry, business, and scholarly work. Bergman points out that “this electronic revolution in the office [word processing] may change who does what sort of work, create some jobs and eliminate others (p. F3).” In fact, in 1977 5.8% of jobs offered in the New York Times mentioned computer literacy skills such as word processing, this number doubled by 1983 (Compaine, p. 136). This was especially evident in clerical positions in which “the proportion of secretary/typist want ads that required word processing skills went from zero in 1977 to 15 percent in 1982 (Compaine, p. 136).” Furthermore, Word processors, coupled with a phone line greatly increased the speed that documents were sent and received. Instead of mailing or dictating documents to another person, documents including graphs and charts could now be written and transmitted, in seconds, over the telephone, more cheaply than previous methods (Bencivenga, p. 11). Scholars “with the help of a computer programmed to scan the text quickly, picking out passages that contain the same word used in different contexts (Compaine, p. 137).” In the early 1980s Word processors and computers fundamentally changed how we process information and thus had much impact on literacy. Compaine refers “to computer skills as additional to, not replacements (p.139)” to literacy and that “whatever comes about will not replace existing skills, but supplement them (p. 141).” Compaine’s essay was written in 1983, but this trend continues today.

Furthermore, the word processor has affected literacy amongst students. In 1983 Ron Truman published an article in The Globe and Mail in which he reported that elementary teachers said word processors were “having a remarkable effect on how children learn to use language: writing on a computer screen improves spelling, grammar and syntax (p. CL14).” An article by Goldberg et al. entitled “The effect of computers on student writing: A meta-analysis of studies from 1992 to 2002″ summarizes that thirty-five previous studies concluded that the “writing process [in regards to K–ı2 students writing with computers vs. paper-and-pencil] is more collaborative, iterative, and social in computer classrooms as compared with paper-and-pencil” and that “computers should be used to help students develop writing skills . . . that, on average, students who use computers when learning to write are not only more engaged and motivated in their writing, but they produce written work that is of greater length and higher quality (p. 1).” Similarly, Beck and Fetherston conclude that “The use of the word processor promoted students’ motivation to write, engaged the students in editing, assisted proof-reading, and the students produced longer texts” and “produced writing that was better using the word processor than that which was achieved using the traditional paper and pencil method (p. 159).”

Different forms of electronic writing have participated “in the restructuring of our whole economy of writing (Bolter, p. 23).” Even as early as 1983, Compaine predicted that in respect to electronic texts, “many adults would today recoil in horror at the thought of losing the feel and portability of printed volumes . . . print is no longer the only rooster in the barnyard (p. 132).” Looking at present day and into the future, the computer continues to reshape and challenge the traditional form of the printed book: “our culture is using the computer to refashion the printed book, which, as the most recent dominant technology, is the one most open to challenge (Bolter, p. 23).” The World Wide Web and most recently the advent of web 2.0 have challenged traditional writing media and the way in which we create electronic media. Word processors have become one tool in an arsenal of programs developed for electronic publishing (such as Dreamweaver for web development, PowerPoint for presentations, iMovie and Movie Maker, and Adobe Flash for animations). As such, literacy still includes traditional texts, but much has been added with digital literacy. Books, magazines, newspapers, academic journals, etc. predominately written using a word processor (or another desktop publishing software), in their traditional form will not be replaced in the near future, but they have certainly had to give up much of their dominance to non-traditional, electronic, writing spaces.

John

References

Barbara R. Bergmann (1982, May 30). A Threat Ahead From Word Processor. The New York Times. p. F3.

Beck, N., & Fetherston, T. (2003). The effects of incorporating a word processor into a year three writing program. Information Technology in Childhood Education Annual, 2003 (1), 139 – 161. Retrieved January 15, 2009, from http://www.editlib.org/index.cfm/files/paper_17765.pdf?fuseaction=Reader.DownloadFullText&paper_id=17765.

Bencivenga, Jim (1980, March 28). Word processors faster than dictation. The Christian Science Monitor. p. 11.

Bolter, Jay David. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print [2nd edition]. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Compaine, Benjamin, M. (1983). The New Literacy. Daedalus, 112(1), pp. 129-142.

Goldberg, A., Russell, M., & Cook, A. (2003). The effect of computers on student writing: A meta- analysis of studies from 1992 to 2002. Journal of Technology, Learning, and Assessment, 2(1). Retrieved November 7, 2009, from http://escholarship.bc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1007&context=jtla

Johnson, Sharon. (1981, October 11). Word Processors Spell Out A New Role for Clerical Staff. New York Times, p. SM28.

Kunde, Brian. (1986). A Brief History of Word Processing (Through 1986). Fleabonnet Press. Retrieved November 7, 2009 from http://www.stanford.edu/~bkunde/fb-press/articles/wdprhist.html

Ong, Walter, J. (1982). Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London and New York: Methuen.

Truman, Ron. (1983, November 24). Word processors prove boon in making youngsters literate. The Globe and Mail. p. CL.14.

November 8, 2009 1 Comment

The school library and the breakout of the visual

In Chapter 4 of his book, Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print, Jay David Bolter (2001) discusses the rise of the visual and its impact on text. As a Teacher-Librarian the rise of the visual in our culture is particular interest to me. As our post-print generation moves through the education system we are being challenged to redefine the nature of libraries and their role in education. In this commentary I view Bolter’s work through the lens of my profession.

Of immediate interest in Bolter’s work is the notion that images on the World Wide Web dominate but images on the printed page are contained by the text that surrounds them. There is an element of control in print culture that is not evident in web-based applications. Specifically mentioned is the way that professional journals and other scholarly texts surround the images they permit and supervise the reading of the image.

Bolter points out that even when images dominate in scholarly text there is little doubt that the text is in a position of control. He refers to this use of image as “textural”. This notion gives rise to the question of whether images in web-based works don’t often provide this same function. When I think of the way that I, my colleagues and my students use images in the products of our learning it seems that they often serve to give texture to the work. Images are frequently included after text is written or are accompanied by explanatory text. This may indicate that our use of image is still in its infancy to some extent. Are those of us born of a predominantly print-based culture slow to learn how to harness the power of the visual?

Bolter questions what is happening to print and prose in what he calls the, “late age of print” (2001) and suggests that text is morphing itself to both compete with and incorporate the proliferation of images and their inherent cultural power. In the school library this is evident in the rise of graphic novelizations of classic children’s books such as the Hardy Boys series by Scott Lobdell and Paulo Henrique. Text in these graphic novels is far less than in the original book versions and are accompanied by images that serve to both complement and supplement the story. Works such as the ground-breaking, The adventure of Hugo Cabret by Brian Selznick offer a combination of text and stand-alone images to tell the story. Additionally, many text-based works now offer web-based links to additional story features and activities based on the books. These applications are largely visual and demonstrate the turning tide children’s literature. An excellent example of this is the 39 Clues series, by Scholastic Press.

Interesting too is the suggestion that this remediation of print is born out of both enthusiasm and fear. Change is generally a feared state of being and as a Teacher-Librarian I am constantly aware of the combination of these reactions to changes in our formerly print-based culture among my professional colleagues. While some embrace and endorse the changes in literacy there are a great number who wish to stem the tide of change in order to maintain their sense of purpose.

Teacher-Librarians, in their quest to maintain the sanctity of the physical library space and all that it contains, are also uniquely challenged by the fact, as Bolter explains, that text is now competing, “for a reader’s attention with a variety of pictorial elements, any or all of which may be in motion” (2001). This increasingly visual world with its cultural expectation of high quality images, special effects and incredible animations makes capturing the attention of today’s students very difficult. Students are often witnessing works of text as image-based before they discover that the material existed in a print-based form long before it was released as a full-length feature movie. There have been a number of films based on children’s literature in the last few years. What Teacher-Librarians are commenting on is how often these movies serve as the first introduction to the material for most children. Eragon, Cloudy with a chance of meatballs, Where the wild things are, and Hoot are some of the many movie scripts derived from books. Many of my professional colleagues criticize these movies and what they perceive as their detrimental effects on reading. However, I often notice in my own practice that these movies often lead my students to seek out the books that the movie plots came from. In this way the text seems to be benefited by the image and draws a new generation of consumers of print into the fold.

The breakout of the visual will undoubtedly have significant impacts on many areas of our culture. This impact will not escape the school library and its keepers. Teacher-Librarians are at a cultural turning point. They will need to find a way to adapt and manage as text changes in the wake the rise of the visual. How well they will fare remains to be seen.

References:

Bolter, J. D. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print [2nd edition]. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

November 8, 2009 1 Comment

Library 2.0 – The Community of the Library

This past week the Toronto Star reported on the reinvention of libraries in the City of Toronto. Though the article does not delve into the deeper issues of knowledge organization, it illustrates how libraries have been evolving to remain relevant within their communities.

Cheers,

Natalie

November 8, 2009 No Comments

Refashioning the Writing Space

Refashioning the writing space for the elementary school student

Commentary #2~ Kelly Kerrigan Section 65A

What does the writing space look like today?

The writing space has undergone many changes in technology, from stone to papyrus to manuscript to computer screen. “Each writing space is a material and visual field, whose properties are determined by a writing technology and the uses to which that technology is put by a culture of readers and writers” (Bolter, 2001, p. 12). Bolter discusses how recording, organizing and presenting text is now done with a word processor and the Internet. One might see this as the modern take of the wall of a public bathroom stall. There are thoughts to ponder, to take away, and others to merely disregard. Sifting through these thoughts can take a moment or a few trips. It is our prerogative to decide what’s worthwhile.

Most adults are aware of changes to our current writing space, but what does that mean for the elementary school student? “Our culture has chosen to fashion these technologies into a writing space that is animated, visually complex, and malleable in the hands of both writer and reader” (Bolter, 2001, p. 13). For a parent of an elementary school student today, this image of the computer and online writing space as being malleable could provoke major fear for their child. This is especially true if the parent has never used the internet during their secondary or post-secondary education years. As a teacher, I have come across many parents who are opposed to using the internet as a writing space. For the children that I teach, their generation needs to be taught how to use this space appropriately and to their advantage, for this is their codex!

Bolter argues that the writing space is a cultural decision. Our current use of the internet as a writing space is a refashioning of the printed book. That being said, do we try to differentiate within this writing space? Do we as readers and writers tend to shun those rants and raves on weblogs and prefer instead those who have posted a document? As if those who took the time to post a document are much more competent in their thoughts than those who write in the common forum or wiki. Teachers must help students discern what is appropriate, but also help them use these spaces effectively.

For the elementary teacher and student, the forum and wiki are great spaces for students to develop their writing skills (McPherson, 2006). Collaboration within these contexts also provides an excellent space for skill development. “Unlike much of the individualized writing required in school and the real world, writing entries in a wiki demands that students be taught writing skills that emphasize negotiation, cooperation, collaboration, and respect for one another’s work and thoughts” (McPherson, 2006). One could imagine the wiki as the technology replacing the bathroom stall!

How does the changing writing space affect literacy?

As Bolter states, “literacy is, among other things, the realization that language can have a visual as well as an aural dimension, that one’s words can be recorded and shown to others who are not present, perhaps not even alive, at the time of the recording” (p.16). Within a wiki, students can use different mediums to enhance their message. “… Students can use wikis to insert music, graphics, video, and photos in their writing and to communicate meanings that were once inaccessible or not fully expressed through the printed word” (McPherson, 2006). This has a huge effect on the overall literacy of a group of students. For those who struggle with writing assignments or with conveying meaning in their work, using a multimodal approach to complement their writing can foster student achievement in literacy.

Research has shown that these new technologies being employed in the classroom challenge the traditional views of literacy (Jewitt, 2005). The technologies that create a new writing space enable a new level of literacy for elementary school students. What it means to be literate in the 21st century is very different from previously set standards. Unfortunately, students are caught between what is written in the curriculum and what is real. Teachers who embrace the new literacy standards are often criticized or held back from trying out new ideas, such as wikis; While older generations of teachers force their students to maintain the literacy levels they were once held to. The refashioning of the writing space for today’s student population involves new technologies, including the use of online writing spaces. All teachers need to embrace these technologies in order to maintain a high level of literacy for their students.

References

Bolter, Jay David. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print [2nd edition]. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Jewitt, C. (2005) ‘Multimodality, “reading”, and “writing” for the 21st century’,

Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 26(3), 315–31.

McPherson, K. (2006). wikis and student writing. Teacher Librarian, 34(2), 70-72. Retrieved from Academic Search Complete database on November 4, 2009.

November 8, 2009 1 Comment

Literacy initiative

Hi all. I thought I’d create a wiki where people could add reviews about their favourite reads, either books, magazine, graphic novels, maybe even web articles. I am pretty open.

I am hoping to get this wiki operational so that I can use it in school next year as part of a reading club for grades 7-12.

Have a look and add a contribution if you like.

If you like to read in French, there is this site as well Juste pour lire.

November 7, 2009 No Comments

Yellow journalism

My brief look at how yellow journalism evolved during the penny press era in response to social, market/economic and technological developments in the late 19th Century is posted here at the wiki site.

November 7, 2009 1 Comment

Revolutionizing information organization and academic authority

Commentary #2 – In response to Michael Wesch’s video, “Information R/evolution” (Module 4)

Appropriately “hyper” for the purposes of framing hypertext and the changing technologies of writing and archiving information, Micheal Wesch’s Information R/evolution is a dynamic interplay of text technologies that incorporates both the hypertext discussion of Jay David Bolter and the organization discussion of Walter Ong. Wesch speaks to the evolution of the pre-typographic notion that information is “a thing… housed in a logical place… where it can be found” and how we have now moved towards a place where technology affords the ability for anyone to create, critique, organize and understand. Information R/evolution touches upon two interesting developments supported by the hypertext environment of our technological world: the nature by which information is stored and the nature of authority.

Information R/evolution starts out with images of the typewriter, standard filing cabinet and card catalogue. This is intentional as each of these three objects were, for many years, definitive symbols of the way by which information was recorded, stored and retrieved. In unpacking the information evolution, these images quickly transform into those of word processing programs, blogs and search engines. Wesch suggests that it does not take an expert to attend to organizational tasks; rather, we are all responsible for the tagging, bookmarking, categorizing and otherwise organizing of information. The organizational affordances of technology are illustrated in the video and echo Walter Ong’s discussion about categories and lists and how they create meaning out of space, impressing through “tidiness and inevitability” (Ong, 2002, p.120). Wesch illustrates this revolution as a true transcendence of place with regards to the means by which information can be rethought “beyond material constraints”. The ability to store information simultaneously in multiple places is not only crucial to the way information is stored but also crucial to the speed at which information is retrieved. Bolter (2001) further discusses this issue in his study of hypertext and cites hyperlinking as the process by which the reader can “continue indefinitely…through the textual space…throughout the Internet” (p.27). An interesting facet of Wesch’s video is that he does not rely on lengthy text to illustrate his point, rather, he demonstrates visually the remediation of print by modeling the organizational affordances of hypertext on a single computer screen, devoid of the paper trail that previously defined information technology.

The nature of authority is touched upon in Information R/evolution and it is suggested that the nature of modern typographic culture has broadened the constraints of previously established information authority (academics, librarians etc.). Information R/evolution raises the issue of how people, either for personal or academic purposes, come to find the information they are seeking and what format they are ultimately presented with. Simply put, “together, we create more information than experts”, is a powerful truth that highlights not only the responsibility of those posting on the web to categorize their information, but also the fact that authorship is seemingly more open. The boundaries of expert and non-expert were more defined in a chirographic and early typographic culture whereby there was an entire process surrounding how one became an author and therefore, an authority. Wesch encourages the viewer to think about authority in the context of this information revolution. While there exists scholarly access points through university libraries, Google Scholar etc., the mainstream user relies on search engines such as Yahoo and Google in order to find definitive sources of information. The breadth of information allows the viewer to view not only authoritative sites (National Geographic, BBC, etc.) but also collaboratively edited sites (Wikipedia) and personal sites (parenting blogs, personal interest sites, etc.) thereby creating a multidimensional approach to any given topic.

However, Wesch indirectly highlights the flip side, which is the uncertainty of the information found. The access itself may be much easier by being able to use one’s personal computer to access library catalogues and search engines rather than searching, in person, through an onerous card catalogue, however, the expanse of the web does lessen the power of established authority. Wesch cites Wikipedia as an example by stating “Wikipedia has 15 times as many words as the next largest encyclopedia, Encyclopedia Britannica”. While this is a seemingly simple statement, it has much larger ramifications for the growing debate about authority on the web, as Wikipedia is a collaboratively created encyclopedia that can be openly edited. More powerful than this statement is the fact that Wesch uses a live screen clip showing himself editing Wikipedia in “real time” and then adding one more person to the tally of the 282,874 contributors that appeared at the time, illustrating the very fluid and “living” nature of information on the Internet. While effective in drawing forth questions about authority and research, I would be interested to see Wesch explore, more closely, the nature of how one conducts research through a similarly styled video.

Bolter speaks of the “breakout of the visual” and in that spirit, Wesch shows that the dominating visual message of Information R/evolution can be just as powerful as written prose exploring the same topic. Wesch’s visual inspires reflective thought about the evolution of information but also the current revolution taking place in terms of information organization, conducting research and the nature of authority.

References:

Bolter, Jay David. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print [2nd edition]. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ong, Walter. (2002) Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Methuen.

Wesch, Michael. (2007). Information R/evolution . Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-4CV05HyAbM

November 7, 2009 1 Comment

Rise of Cinema

“Few people will deny that the cinema has become one of the most powerful of influences in modern society. It is necessary, first, to recognize the twofold aspect of the cinema as an educational force. On the one hand, it is an instrument, one among many others, for achieving certain definite results: for example, the vivid presentation of facts and ideas which it is desired to impress upon children’s minds; the giving of knowledge which could be only very inadequately depicted in words or by static presentation; the representation of growth and movement; the simplification of complicated processes. It has also a second aspect: it is a method by which the human mind can be affected and directed”.

When I was searching the UBC library, I found the above sentences from Barbara Low’s article in contemporary review journal. I really liked her ideas about cinema; they seems to be correct and clear. Meanwhile, she wrote them eighty four years ago! Yes, I was also shocked when I found her article published in 1925 on the old paper. And after 84 long years, what should I add to her thoughts for Cinema?

The power of cinema is indisputable. Since the beginning of cinema, a little over a hundred years ago, it has captivated audiences. We want, badly, to watch. And this power seems unique to film. As the philosopher Stanley Cavel remarks “the sheer power of film is unlike the powers of the other arts” (McGinn, 2005).

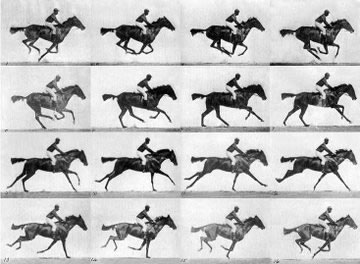

The arrival of cinema at the close of the nineteenth century immediately excited public imagination. Cinema can be considered as the illusion of movement by the rapid projection of many still photographic pictures on a screen. In fact, no one person invented cinema. In 1878, under the sponsorship of Leland Stanford, Eadweard Muybridge successfully photographed a horse named “Sallie Gardner” in fast motion using a series of 24 stereoscopic cameras. The experiment took place on June 11 at the Palo Alto farm in California with the press present (Clegg, 2007).

picture of “Sallie Gardner”

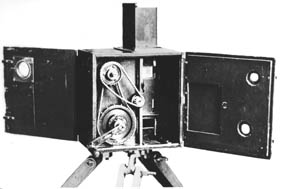

In 1893, Thomas Edison and his chief engineer Dickson successfully demonstrated the Kinetoscope, a motion picture system that enabled one person at a time to view moving pictures. Two years later, Lumiere brothers used the cinematograph to project moving photographic pictures onto a screen to a paying audience for the first time in a Paris cafe. Their machine was light, neat and versatile, serving as printer as well as camera and projector.

The standard Cinématographe Auguste and Louis Lumière

This was the beginning of a long journey. By 1914, several national film industries were established. Films got longer and story telling, or narrative, became the dominant form. As more people paid to see movies, the industry that grew around them was prepared to invest more money in their production, distribution and exhibition. Large studios were established and special theatres built (National Media Museum). In fact, the early histories of film lie in the rise of consumer culture.

Cinema has been an important means of shaping public opinion in its history. In England the Committee on Public Information produced such films as “The Kaiser: The Beast Of Berlin”, and Charlie Chaplin made several propaganda films, including one promoting British war loans. Cinema was also influential in wartime France. In 1917 Griffith filmed “Hearts of the World” in France, showing realistic battle scenes and the mistreatment of civilians by Germans, which reportedly boosted recruitment in the U.S. (Nebeker, 2009 ).

Lots of people thought that cinema could advance progress toward mass literacy. They believed that technologies such as cinema would radiate a utopian promise of ultimate democratic enlightenment. Edison, for instance, believed that cinema would bring about the perfection of education. He said that “I intend to do away with the books in the school….When we get the moving pictures in the school, the child will be so interested that he will hurry to get there before the bell rings, because it is the natural way to teach, through eyes” (Naremore, Brantlinger, 1991). In 1925, a headmaster of a school with 300 pupils, ranging from seven to fourteen years of age, stated that he has found the cinema of the highest value as an adjunct in imparting instruction in general science, geography and history (Low, 1925). He also reported “children remember what they see, though they forget what they hear.” However, the following years proofed that those initial ideas were very optimistic.

For instance, let’s consider movies’ effects in Hawaii education system. Since the 1930s, Hollywood has embraced Hawaii as a sultry paradise in film classics such as Bing Crosby’s “Waikiki Wedding”, Elvis Presley’s “Blue Hawaii” and classic World War II movies such as “From Here to Eternity”. Even today, more than 100 film and TV shows have been shot in Hawaii. Hawaii has two official state languages: English and Hawaiian. Throughout the last century as more and more Americans and British settled in the islands and developed movie industry and lots of jobs in this field were created, the everyday use of Hawaiian declined. Later, speaking Hawaiian was even seen as a deterrent to American assimilation, thus adult native speakers were strongly discouraged from teaching their children Hawaiian as the primary language in the home. This attitude remained until the early 1970s when the Hawaiian community began to experience a cultural renaissance (Grant, Bendure, 2007). It seems that, from time to time, cinema can affect process of reading/writing in an unexpected ways.

Effects of cinema on different classes of societies should not be ignored at all. Jacobs (1967) believed that the power of cinema has been a major problem of the social revolution it reflects; for one thing, to persistent pressure for restriction of content and presentation, not only for ideological purposes of control over forces of influence and persuasion, but on the part of religious, parental and educational groups concerned with effects upon the young.

In England, in the majority of 1950s war films, the role of middle class of society in winning the war was heavily emphasized. The main reason was due to fear that middle class of society had an alliance between upper class and worker class. The great Victorian invention, the middle class, had always affected to despise both these other classes, although remaining ready to allow the upper class to rule and the working class to work as long as its own class position as backbone of England, remained undisturbed. The promises made or implied by a people’s war seemed to offer consolidation of that position and to have improved along with improving the conditions of working class (Dixon, 1994).

According to Bolter’s (2001) concept of remediation, each technology claims to be superior to the one it sets out to remediate. This was also valid for cinema. In 1930s in Soviet Union, Stalin began to perfect the techniques used by Lenin in the civil war of deploying non literary modes of mass propaganda. Soon it followed more effectively by the fascist regimes in Italy and Germany, learned how to use the inventions of new century to solve the problems of the old. The dark forests of oral communication, which 19th century governments had sought to open up with the written word, were now invaded by devices which bypassed print altogether. Later as some kind of peace was achieved, so the technological developments of the era, especially the cinema, were pressed into the service of the totalitarian state (Vincent, 2000).

According to Henderson (1992), cinema and its effect on the rise of a celebrity-based culture in this century can in part be attributed to America’s change-over from a producing to a consuming society. It also has to do with the shift in our cultural perspective that occurred in the late nineteenth century. The essential power of the cinema lay in its specificity. Cinema is both the space of isolation and the space of shared experience and its presence in our culture is significant (Harvey, 1996).

Power of cinema can also affect cultural identities of youth and young adults in different societies. In the mid 1950s, the gradual relaxation of the Hollywood production code and the growth of independent filmmaking brought to the forefront a whole series of American movies which openly explored taboo breaking subjects about sexuality, crime, and the use of drugs. One series of movies causing a heated public controversy dealt with the social problem of juvenile delinquency. Films like The Wild One, with Marlon Brando in 1953, directly confronted the issue of postwar youngsters’ crime and gang life, initiating cycles of teenage exploitation films often called juvenile delinquency movies.

In the U.S., these successful film cycles about the misbehavior of rebellious post war baby boomers sparked a wider controversy about the increase in juvenile crime, the failing educational system, and the loss of family values in American society. The movies only increased the anxious inquiries from different parts of the society. What is so interesting about these 1950s juvenile delinquency movies is that they could stir up such a heated debate across various groups and organizations. Everyone from the average audience to the U.S. Senate, including leading journalists, intellectuals, politicians, and religious leaders, was moved to raise their voices about these movies’ effects on endangered core social values. This situation, where various moral guardians express their concern over key values, often signals a society wide moral panic. The controversy and moral panic were not restricted to the U.S. In the U.K. and other European countries, a wider public debate addressed juvenile delinquency and the influence of imported American movies (Biltereyst, 2007).

Despite a century of development cinema, with a huge industry, is still a young event. Cinema was not invented. Nor was it precisely a process of evolution. Rather it was the realization of a conception that had been clearly envisioned for centuries before. Edison, Dickson, Paul, the Lumieres merely chanced to be the ones privileged to add the last elements to the building that had been foreseen and in the making for many generations (Robinson, 1996). Perhaps, it is better to say that movies are not documents of their time; they are feelings of their time. Its effects on culture, reading/writing, mass literacy, politics of the societies can not be ignored. In general, emerge of cinema at the end of the nineteenth century initiated a movement from text culture to visual culture societies.

Let me finish what I started with some sentences from Barbara Low (again!) about cinema written eighty four years ago. “It is, therefore, very much worth while to consider to what extent this extremely powerful force of the cinema may help or intensify different attitudes”.

References

Biltereyst, Daniel. American juvenile delinquency movies and the european censors, in youth culture in global cinema, edited by Timothy Shary and Alexandra Seibel, University of Texas press, Austin, 2007.

Bolter, Jay David. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print [2nd edition]. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Clegg, Brian (2007). The Man Who Stopped Time. Joseph Henry Press.

Dixon, W. Winston. Re-viewing British cinema, 1900-1992, State University of Newyork Press, Albany, 1994.

Grant, K. Bendure, G. Hawaii, Lonely Planet. 2007.

Harvey, Sylvia. (1996). What is cinema?, in Cinema: the Beginnings and the future, edited by Cristopher Williams, University of Westminster press. London.

Henderson, Amy, (1992). Media and the Rise of Celebrity Culture. OAH Magazine of History, Spring 1992.

Jacobs, Lewis. The rise of the American film. Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, 1967.

Low, Barbara. (1925). The Cinema in Education: Some Psychological Considerations. Contemporary Review, November, 1925.

McGinn, Colin. The power of Movies. Pantheon Books, New York, 2005.

National Media Museum. http://www.nationalmediamuseum.org.uk/pdfs/cineHISTORY.pdf

Naremore, James. Brantlinger, Patrick (1991). Modernity and mass culture, Indiana University Press, 1991.

Nebeker, Frederik. Dawn of the electronic Age: Electrical Technologies in the Shaping of the Modern World. John Wiley & Sons. Newjersy. 2009.

Robinson, David. (1996). Realising the vision: 300 years of cinematography, in Cinema: the Beginnings and the future, edited by Cristopher Williams, University of Westminster press. London.

Vincent, David. (2000). The rise of mass literacy: reading and writing in modern Europe. Pility Press, UK.

November 5, 2009 No Comments

Pioneer of the Visual

I do admit, I love Steven Jobs! Here is a clip about a new book on his presentation secrets. Note that he is called a master storyteller (back to our oral roots?) and that he uses visuals (slides) to create maximum impact (the breakout of the visual?). This seems like a perfect example of multimodal communication where our use of visuals is allowing us to return to orality.

It’s a shame the book does not actually include interviews with Steve Jobs. (I wonder if the book is available in an electronic format?) 🙂

November 5, 2009 No Comments

Eye Tracking

My husband works for Enquiro and they do market strategies for search engines. The are a small Kelowna, BC company but all of their business is large US corporation and the major search engine players. The recent reading by Bolter and Kress made me think of the connections to what this company has to offer. One line of Enquio’s business is eye-tracking research – they capture where people look on a screen and create an image of it. I have taken part in these studies and have seen the images of where by eyes have looked. Very interesting technology and very powerful for the company’s to utilize. If you are interested take a look.

November 4, 2009 1 Comment

Language as Cultural Identity

Language as Cultural Identity

Russification of the Central Asian Languages

Pier Borbone asserts that “there is no obligatory relationship between language and writing: per se, every language can be represented with any graphic system, even systems originally created for other languages – if necessary with certain adaptations.” (Borbone, 2007) He further theorizes that “the decision to adopt a certain kind of script depends to a large degree on other considerations, not having to do with the language itself, and that the choices of script made by different peoples and nations are an interesting clue to cultural, political and religious aspects of their history.” (Borbone, 2007)

The former Soviet Union provides an interesting case study when looking at cultural and political implications of using an already existent script for historically and culturally rich but very different languages which already had been using a different script. Specifically looking at the adoption of the Cyrillic alphabet to the Central Asian and Far Eastern languages, we can examine the Russification of these particular languages and cultures.

With the creation of the new Soviet Union came many challenges. One of the major challenges was to create an identity and somehow unify over 100 different ethnic groups. A systematic policy of Russification was adopted by the early Soviet government but it was by no means a new development. Russification dates back to the 16th century with the conquest of Khanate of Kazan and other Tatar areas. At its early stages, Russification mostly involved Christianization and implementation of the Russian language as the sole administrative language.

The Cyrillic alphabet was created by St. Cyril and his brother St. Methodius, who were Byzantine missionaries and were sent to convert the Slavs to Christianity. The original alphabet was known as Glagolitic from which modern day Cyrillic evolved.

Glagolitic alphabet

Cursive version of the Glagolitic alphabet

http://www.omniglot.com/writing/glagolitic.htm

1918 version

The names of the letters are in Russian.

http://www.omniglot.com/writing/cyrillic.htm

Languages written with the Cyrillic alphabet

Abaza, Abkhaz, Adyghe, Archi, Avar, Azeri, Balkar, Bashkir, Belarusian, Bulgarian, Buryat, Chechen, Chukchi, Church Slavonic, Chuvash, Dargwa, Dungan, Erzya, Even, Evenki, Gagauz, Ingush, Kabardian, Kalmyk, Karakalpak, Kazakh, Komi, Koryak, Kumyk, Kurdish, Kyrghyz, Laz, Lak, Lezgi, Lingua Franca Nova, Macedonian, Mansi, Mari, Moksha, Moldovan, Mongolian, Nanai, Nenets, Nivkh, Old Church Slavonic, Ossetian, Russian, Ruthenian, Serbian, Slovio, Tabassaran, Tajik, Tatar, Turkmen, Tuvan, Tsez, Udmurt, Ukrainian, Uyghur, Uzbek, Votic, Yakut, Yukaghir, Yupik

http://www.omniglot.com/writing/cyrillic.htm