Introduction

Reading today is a silent and solitary activity, in the West its roots lay in the oral tradition. Saenger (1997), who has researched the spaces between words and punctuation extensively, notes that reading was originally an oral activity, and that the processes and tools that we use to make sense of the written word have not always been the same. The spaces between words, and indeed punctuation, are, in the history of reading/writing relatively new inventions and have evolved significantly over the past millennium. Manguel (1996) notes writers in antiquity made the assumption that readers (listeners) preferred to hear text, not read it, and furthers by noting that present-day sayings such as “This text doesn’t sound right”, speak to these origins. From the perspective of literacy, word dividers and punctuation are powerful inventions which “freed intellectual capacity of the reader to read silently.” (Saenger, 1997, p. 13) In this essay, the historical significance of the technological advent of word dividers and punctuation is explored alongside discussion on how literacy and education were impacted.

The World Without Word Dividers

The Rosetta Stone, which provided the key to understanding Egyptian hieroglyphics, is a clear example of three languages representing both graph- and letter- based writing systems in which word spaces and other modern tools such as capitalization and punctuation are not used. Languages that use logographic writing, in whole or in part, such as ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs and contemporary Mandarin and Japanese are written without spaces between words. Japanese newspapers provide a good visual example as to how modern Japanese is rendered without spaces.

In the present day, one thing that many students of Japanese express discomfort with is the lack of separation between words (see note). At a rudimentary level, Japanese is written, as Saenger (1997) notes, in kana (syllabic Japanese script not dissimilar to the English alphabet). Students inevitably break words apart using spaces, because kana, like letters, do not have meaning per se in the way that Chinese characters do. While Saenger’s description of reading in Japanese is somewhat incorrect and lacks depth of understanding of how kana are used in conjunction with Chinese characters (e.g. verb infliction), he is correct in noting that characters themselves aren’t “read” in the Western sense. Rather, they intrinsically have and convey meaning whereas individual letters and kana do not. In other words, Chinese characters, by themselves or in combination, have meaning.

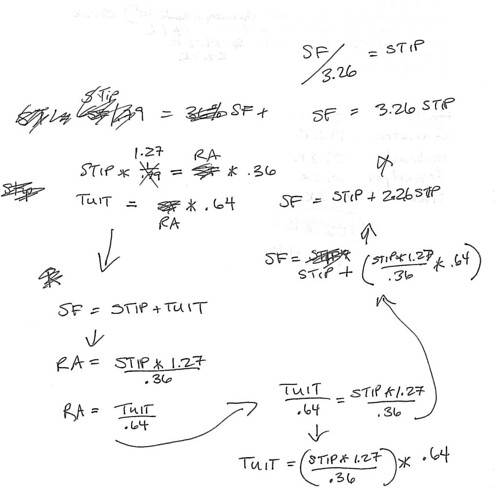

A useful analogy is reading math equations. The = sign has a meaning that we “read” as equals and it conveys a clear meaning/concept. Thus, a simple equation such as 12/7-4=0 requires no spaces for comprehension. doingthesamewithenglishtextisextremelydifficultespeciallyforlongpassagesoftext. Indeed, for a work of any length written without spaces between words, deciphering meaning and reading with any sense of flow is extremely difficult. In the West, it is difficult to imagine text without spaces, and yet, that is exactly how English and other languages were first written.

From Scriptura Continua to Spaces Between Words

As mentioned, manuscripts and other written works historically were written without spaces between words and punctuation, and text in scriptura continua (or scriptio continua) were long strings of uninterrupted and unpunctuated text. In antiquity, there was no need or desire to identify ways to make reading easier (Saenger, 1997). Literacy was not wide-spread, and the limited number of texts available were read aloud slowly. Reading was a very different process. In the first century, Quintilian stated that for orators in learning reading: “It is through the practice of reading that the child will learn where he should breathe, and where he should separate each line.” (Ponbo, 2002, p. 32) Given that it was oral, Ong (1982) suggests that reading in this sense was as much about listening as it was about reading. He furthers by suggesting that memorizing text helped those reading since “in highly oral manuscript cultures, the verbalization one encountered even in written texts often continued the oral mnemonic patterning that made for ready recall.” (Ong, 1982, p. 117)

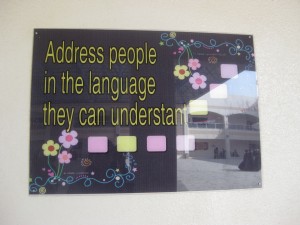

Reading Latin and Greek text in scriptura continua, Saenger (1997) contends, was a difficult and mentally draining art, and the eyes need to be kept ahead of the text. He argues that it was the introduction of word separation around the seventh century that helped allow the development and advent of oral readings much quicker cousin, silent reading. The spaces between words had a clear impact on helping build and enable literacy, but associated with this growth is a loss of how learning and communication took place in oral cultures. The change to silent reading is described by Parkes (1993) as a shift to “conveying information directly to the mind through the eye.” (p. 1)

Punctuating Text

If the spaces between words are one piece, then how punctuation played into the change in the way text was written and rendered is another key development. Punctuation, from the Latin punctus (meaning point) was used by Roman teachers (grammatici) as a way for students to distinguish between words or phrases (Parkes, 1993). Adorno and Nicholsen (1990) suggest that one of the distinguishing features of (present day) punctuation is that more than anything else, punctuation marks are similar to music. One example they offer is that of the question mark and the accompanying rising intonation in interrogatives.

Similar to the way that spaces between words act as “guideposts” (Saenger, 1997, p. 15), punctuation has a clear role in serving to help readers make sense of text. Parkes (1993) argues that punctuation was originally an aid to reading aloud, and differed from its later uses. For example, the interpunct and slash in their earlier use, were used for word separation, not punctuation marks. In other words, they aided the reader (orally) in deciphering text, but did not offer the benefits that later developments did for the silent reader. The introduction of the printing press in the fifteenth century paved the way for more standardized use of punctuation and other refinements such as indented paragraphs in text that are common today (Parkes, 1993).

Similar to the way that spaces between words act as “guideposts” (Saenger, 1997, p. 15), punctuation has a clear role in serving to help readers make sense of text. Parkes (1993) argues that punctuation was originally an aid to reading aloud, and differed from its later uses. For example, the interpunct and slash in their earlier use, were used for word separation, not punctuation marks. In other words, they aided the reader (orally) in deciphering text, but did not offer the benefits that later developments did for the silent reader. The introduction of the printing press in the fifteenth century paved the way for more standardized use of punctuation and other refinements such as indented paragraphs in text that are common today (Parkes, 1993).

Implications on Literacy

Both punctuation and word dividers were powerful advances in text that provided critical tools for silent reading to develop and become widespread. Word separation enables readers to readily identify words and turn their attention to meaning (Saenger, 1997). By the time the printing press was invented, both word separation and punctuation were well-established, but standards were lacking, particularly in terms of punctuation (Parkes, 1993). As the printing press became more widely used, conventions began to take root and these further aided literacy. Standardization made it much easier for readers to silently decode text authored by a variety of individuals ( Saenger, 1997). Furthermore, the organization of text that occurred with these innovations made words, clauses, sentences and paragraphs easily distinguishable. Saenger (1997) adds that the act of silent reading, in particular, shifted the “neurological process of reading” (p. 13).

Conclusion

As illustrated, text without spaces between words and punctuation leaves contemporary readers of English lost trying to read text of any length with any degree of fluency. Even this sentence, the dependent clause with commas as bookmarks, offers a case in point as the punctuation makes deciphering the content much easier and avoids potential misunderstanding. In the evolution of writing, these inventions have played a critical role in advancing literacy and making text accessible for the average person. Even in the absence of v w ls, w c n d c ph r nd c mpr h nd t xt in many instances. The same text without spaces between words becomes increasingly incomprehensible (s m l tt rs, w c nd c ph r ndc mpr h ndt xt) as the spaces between works, a critical element of silent reading is removed. Scriptura continua still exists in languages that use letters, such as Thai, but most non-logographic languages use conventions such as spaces between words and punctuation. Of interest now is how digital media is beginning to challenge how we read and decipher mixed media messages online. It seems apparent that as renderings of text and information continue to change, our notions of literacy and reading will continue to evolve.

References

Adorno, T. & Nicholsen, S. (1990). Punctuation Marks. The Antioch Review, 48(3), 300-305. Retrieved from JSTOR database.

Manguel, A. (1996). “Chapter 2: The Silent Readers”. In A History of Reading. New York: Viking). Retrieved from http://www.stanford.edu/class/history34q/readings/Manguel/Silent_Readers.html

Ong, W. (1982). Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London: Routledge.

Parkes, M. (1993). Pause and Effect: An Introduction to the History of Punctuation in the West. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Pombo, E. (2002). Visual Construction of Writing in the Medieval Book. Diogenes (International Council for Philosophy and Humanistic Studies), 31-40. Retrieved from Humanities Full Text database.

Saenger, P. (1997). Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading . Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Note: I have taught language, including Japanese, for a number of years at the post-secondary level in Canada, and comments on students of Japanese are based on observations from that experience.

Orality, Literacy, and Education

It is difficult if not impossible for a person living in a literate culture to truly understand what living in a primary oral culture would be like. A primary oral culture is defined by Walter J. Ong (1982, p.11) as one that is completely void of any knowledge of writing or print while a secondary orality is a new orality ‘sustained by telephone, radio, television, and other electronic devices that depend for their existence and function on writing and print’. In an oral culture knowledge must be stored in the collective memory of the people, not in texts written by people. The concept of looking something up does not exist. In ‘Orality and Literacy’, Ong discusses the differences between oral and literate cultures, and makes an argument that thought processes in literate cultures are different than those in primary oral cultures.

‘Without writing, the literate mind would not and could not think as it does, not only when engaged in writing but normally even when it is composing its thoughts in oral form. More than any other single invention, writing has transformed human conciousness.’ (Ong, 1982, p.77)

Ong describes thought in an oral culture to be carried out in mnemonic patterns to increase retention and states that serious thought is sustained by communication and must be memorable. For example, after thinking through a solution to a problem there is no way to leave a permanent solution for others to see, therefore communication of information in a memorable way is vital if the solution is not to be lost. The characteristics of thought in an oral society are described as being additive, aggregative, redundant, conservative, agonistically toned, empathetic, participatory, situational, and close to the human lifeworld. In an oral society memories which have lost their relevance to the present are quickly lost (Ong, 1982).

The invention of writing allowed thoughts to be captured and to live on, unlike verbal words which are lost immediately. Written text is described as ‘context-free’ as it is read separated from the author and cannot be directly questioned as the speaker of language can be. Although text is accused of destroying personal memory it also functions as a permanent record or external memory for a society. Members of a literate society have thought processes that rely on the technology of writing and tend to be analytic and dissecting, rather than the aggregate and harmonizing tendencies of thought by members of an oral society (Ong, 1982).

Ong’s analysis of oral and literate societies is classified as a ‘Great Divide’ theory for suggesting that such different modes of thinking exist in the two different types of societies. Others criticize the idea that a single technological invention such as writing could create such a divide and suggest that a continuum rather than a dichotomy exists between oral and literate societies.

‘Those in non-literate societies do not necessarily think in fundamentally different ways from those in literate societies, as is commonly assumed. Differences of behaviour and modes of expression clearly exist, but psychological differences are often exaggerated.’ (Chandler, D., 1994)

Chandler (1992) points out there is a danger of viewing oral societies as inferior to literate cultures such as our own, especially when the differences are portrayed as a dichotomy. He discusses how research shows many similarities exist between oral and literate societies that should not be overlooked. Differences exist amongst oral cultures that can be as significant as those between oral and literate cultures. He argues that there is not a distinct divide between oral and literate cultures as most societies and individuals show variety in their use of oral or literate modes of communication depending on the situation.

While discussing education and technology, Neil Postman states ‘orality stresses group learning, cooperation, and a sense of social responsibility’ and ‘print stresses individualized learning, competition, and personal autonomy.’ For four centuries teachers have been carrying out a balancing act between dominant print texts and orality in the classroom (Postman, N., 1992, p.17). According to Postman (1992, p.20), we now need to consider not the best use of a computer as a teaching tool but how the computer is altering our interests, our symbols, and the nature of community.

I found Ong’s analysis of primary oral cultures and literate cultures extremely interesting despite finding it hard to believe that the invention of writing has single-handedly transformed human thought processes. I see value for educators in Ong’s work of explaining the thought processes tied to orality and literature as the knowledge can be used when choosing delivery methods based on the educational setting and learning goals. Computers need careful consideration as a technology that is capable of blending literate and oral modes between learners that are physically separated.

References:

Chandler, D. (1994). Biases of the Ear and Eye: “great Divide” Theories, Phonocentrism, Graphocentrism & Logocentrism [Online]. Retrieved, 10 October, 2010 from http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/litoral/litoral.html.

Ong, Walter. (1982.) Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London: Methuen.

Postman, N. (1992). Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. New york: Vintage books.