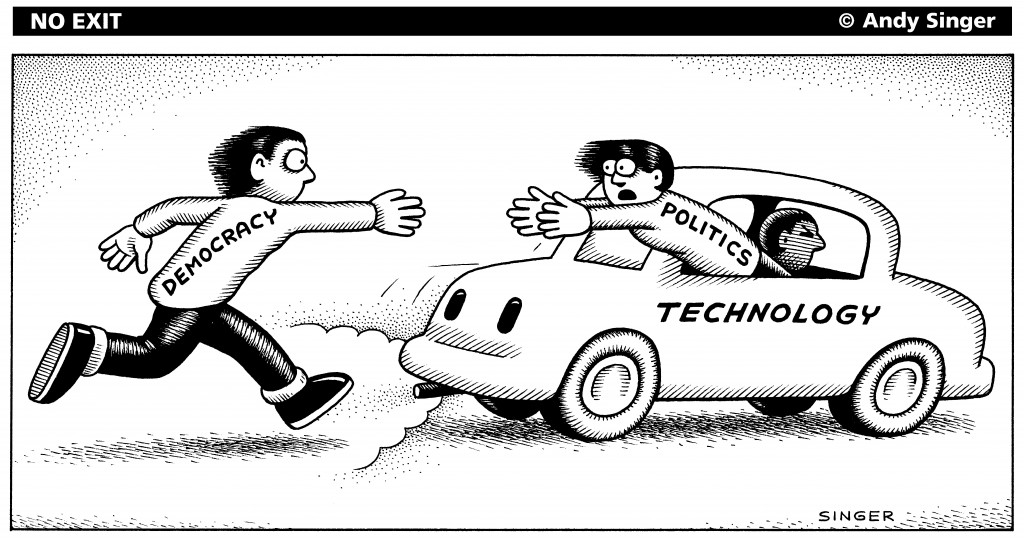

There is, in the world, real and perceived social and economic gaps that exist between cultures, societies, countries and even within such geopolitical entities. These gaps or divides often separate the world into those who have and those who have not, feed local and global conflicts, drive environmental degradation, marginalize groups and individuals, and are perpetuated by economic interests and political power. Technology, of course, is often considered to be central to such divides. At the same time, technology is also looked to and advanced in ways that potentially bridge and eliminate such divides. Further, there is at present a divide that exists within context of advancing technologies called the digital divide where some across the globe have access to 21st century technologies while others are seemingly excluded. It is from these contexts that the role of technology will be considered here. More specifically, by comparing and contrasting perspectives on writing and print technologies with emerging perspectives on digital technologies and examining ideas around the neutrality of technology, in the work of Ong (1982), Postman (1992), Chandler (1994) and Petrina (2008), we can better understand the role of technology in the potential creation and elimination of social, economic, and political inequities mentioned above.

In chapter 4 of his text Orality and Literacy, Ong (1982) posits that writing, with its use of tools and artificial orientation, is to be considered a technology. Further, Ong articulates that print technologies and digital (computer) technologies are then extensions and evolutions of this original ‘drastic’ technological leap from orality. For Ong the literate culture supported by writing and print technologies is one that is fundamentally different from purely oral cultures where human consciousness is transformed and a deeper human potential can be realized. If we accept this perspective it would follow that those who have access to such a technology would have an advantage over those who did not.

Gleaned from Ong’s discussion and text is the idea that as written or print literacy takes hold in a culture the significance of print begins to provide, not only deeper intellectual affordances but also, real political power where the (real or perceived) legitimacy of written literacy trumps that of oral literacy. The use of the written word in law and court proceedings stands as an example here. In the development and evolution of print literate cultures some groups adopt and gain access to this technology before others. When print begins to wield political power this puts a knowledge power structure in place that create inequities. Ong outlines this ‘power monopoly’ as he casts the light on various early written languages that became the exclusive domain of an exclusive male culture. This theme of technology politics is present in the discourse and spread of modern digital technologies.

The lack of political neutrality inherent in modern technologies including digital technologies is seen to have created a divide where some experience political and economic power while others are left out (Chandler, 1994; Postman, 1992; & Petrina). In Chandler’s (1994) review of literature on this theme the inherent biases built into technologies including beliefs about progress, modernity, and the resulting social structures that use and are influenced by technologies is explored as evidence of the technological determinism and lack of neutrality present in technology. In his reflections on writing technologies and computer technologies, Postman’s (1992) Thamusian skepticism is framed by the idea of technology being intrinsically non-neutral. He questions the power inequity that is established when a perceived wisdom and reverence that is granted to those who are knowledgeable in relation to particular technologies. Further, among other criticisms Postman suggests that the ideologies, values and beliefs that are part of the technological design process are complicit in putting the values of one perspective over another, or more succinctly a society of winners and losers.

It is interesting to consider the pessimistic classroom computer use example Postman uses near the end of his, now somewhat dated, chapter ‘The Judgement of Thamus.’ Here he offers support for his position of technology carrying a bias by suggesting that the use of computers in classrooms, by their design, will be likely to result in an academic culture that is purely isolated, individualistic, and lacking in community. This of course seems antithetical to much of the learning theory embedded in educational technologies that promote collaboration, open dialogue and, a cultivation of a community of learners. Petrina (2008) although equally skeptical of the underpinning biases inherent in technologies offers a competing view of educational technologies to that put forth by Postman.

In his work, Petrina (2008) urges educators to avoid the autonomous learning culture Postman hypothesizes. The suggestion is that by embracing open-source technologies that are by nature communally developed educators will be supporting learning that is collaborative. Further, supporting open access and the free circulation of ideas we can move closer to the virtues of learning in oral cultures where cooperation, community and social responsibility are emphasized (Postman, 1992; p. 17). Still technology has always been looked to as a panacea for bridging political and cultural divides and if the logic follows open-source technologies too are not neutral and will contain a bias that supports one view at the expense of another as Postman, Chandler and Petrina have suggested.

References:

Chandler, D. (2000). Technological or media determinism. Retrieved from http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/tecdet/tdet01.html

Ong, Walter. (1982.) Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Methuen.

Postman, N. (n.d.). Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Petrina, S. (2008). The Politics of Educational Technology, Module 5, 1.1 Politics,

Technology and Values. Retrieved November 7, 2008, from https://www.vista.ubc.ca/webct/urw/lc5116011.tp0/cobaltMainFrame.dowebct

Orality and literacy: Supremacy or convergence?

As cultures emerge, their needs evolve and transformations occur. This brings about a lot of changes. Evidently, this triggers schools of thought, promoters, antagonist, neutralists etcetera. Each school presents arguments or positions that matter to them. Ultimately, they each take their stand thinking it is for a good purpose.

The changes that occur in a culture is also in itself to serve a perceived need, hence from oral to literate to electronic cultures, these groups of people of schools of thought remain common denominators.

An innovation or invention is usually perceived as “futuristic” and this creates within the culture, a fear of the unknown which usually presents as the different schools of thought.

Reading through this history as presented in (Ong 1982, ch.3-4), the idea comes across to me that these changes come about not to eradicate the existing or status quo, but rather to consolidate them. Presently, the electronic culture has given a voice to both the oral and literate cultures, in the former (orality), through audio/visual recording and the latter (written word) through emails and chat. Thus the new innovations or inventions make the previous more potent and effective in serving the current and future needs of society. Thus these innovations herald the shift from one culture to another.

These changes seen as technologies appear to be man’s effort (consciously or unconsciously) to refine that which is already in existence in order to communicate better and be more inclusive in approach.

In the end, it all strives to bring unity, while not denying individuality. The electronic culture has emerged to aggregate the oral, written and printed word (technologies)to create a unity while still keeping the individual character of each of them.

“Technologies are not mere exterior aids but also interior transformations of consciousness” (Ong 1982, p.81)

If we perceive writing as a technology, can we also argue that speaking is a technology that came about following man’s desire to communicate more intelligibly?

Ong rightly pointed out the resistance faced by each new innovation from writing to printing to computers. (Ong 2002, pp.78-79).

The recurring arguments in each culture hinges on memory, man’s ability to retain knowledge and originality, man’s ability to produce “authentic” knowledge.

For Socrates, in his oral culture, writing seemed like an innovation that will make man’s brain redundant, “Those who use writing will become forgetful, relying on an external resource for what they lack in internal resources. Writing weakens the mind.” (Ong 1982, p.78)

A closer look at this statement makes me wonder if Socrates words by Plato in the Phaedrus (274-) were indeed prophetic; with the spate of “Google it” going on among school age children (and in society at large) who seem to think there is no need to think any concept through when there is a resource they can “access.”

It makes me wonder how computers have affected the thinking of the electronic culture. I wonder if this has produced a thought process of “e-cheating” in our electronic age hence the issue of originality comes into question like Socrates implied centuries ago.

Printing to Heironimo Sqarciafico was a destructive tool to man’s memory. “Abundance of books makes men less studious” (quoted in Lowry 1979, pp. 29-31): it destroys memory and enfeebles the mind by relieving it of too much work” (Ong 1982, p.79)

The reference here by Ong was the pocket computer, which even though it has a lot of benefits does however seem to impede thinking. You do not need to memorise how to get to a location anymore when your pocket computer has a GPS. Infact, you do not need to remember how you got there the first time if you had to do it again. You simply rely on the GPS to think it through.

While, I agree with Socrates about one thing; “writing pretends to establish outside the mind what in reality can be only in the mind. It is a thing, a manufactured product.” (Ong 1982, p.78), I think that to say that those who use writing will become forgetful is rather preposterous on his part.

Socrates had no idea what the fall out of writing would be at the time because he had not tried it or seen people who had tried it and attest to his proposition. His statement does however bring a few questions to mind.

Why do I keep a journal? Does the singular act of writing in my journal destroy my memory or my ability to remember things?

Am I using my journal as my databank or as a backup to my memory? If something were to happen to my journal, what becomes of my expressed thoughts? How has journal keeping or writing affected the way I think?

The impact of these innovations and the shift from one to the other cannot be denied for it is indeed something to ponder.

How do these innovations affect how we think?

Are these innovations creating different forms of thought, i.e. are the thought patterns of the oral, literate and electronic cultures truly different one from the other?

According to Ong, the literate cultures are more objective in their thinking (Ong 1982, pg.112). As much as Ong considers this a plus, it does have a negative side, it shows that text is not capable of being humane and that implies that a literate society may also create a self absorbed thought pattern

How do they affect what we retain not just in our memories but in our society?

The oral cultures may have lost some information in the process of transfers over time, but not intentionally. It would have been a conscious effort on this culture to task their memories to remember things clearly. I think that for most of them, they would have developed a photographic memory.

In the final analysis, I would say that new innovations or technologies do influence how we relate to our environment (people, attitudes, etc). They are largely change catalysts but with each innovation, from oral to written, to print and to electronic, it is clearly a way to enhance that which already exists. Each innovation or technology is an advancement over what existed before it so it cannot be judiciously compared to the other as each comes about and exists to serve the needs of its era.

References

Ong, Walter. (1982.) Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London: Methuen.

Postman, N. (n.d.). Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. New York, NY: Vintage Books.