New literacy in the Digital Age: understanding the dynamics of needed information and media competencies in a post-secondary educational setting.

Introduction

As we progress through the early stages of the twenty-first century, we are witnessing a dramatic change in the use of traditional text and words; they are rapidly being augmented and replaced with images. These images are becoming central to communication and meaning making and are no longer there to only entertain and illustrate (Mitchell, 1995). Thus we are quickly moving into a media rich, visual world made possible with advancements in computer technologies. In 2008 for example, the photo sharing site, Flickr, had more than two billion images and in January 2008 YouTube had 79 million viewers and 3 billion videos (Felton, 2008). This visual, screen-based world is the domain of today’s post-secondary students who are visual learners, “intuitive visual communicators” and “more visually literate then previous generations” (Oblinger and Oblinger, 2005, ch. 2.). This pervasive new form of media requires the development of knowledge and skills to help value and interpret what they mean.

Information, whether it be text or visual based, is more abundant today through the Internet, then it was 20 years ago. Individuals no longer need to go out of their way to search for information by going to the Library. Today proliferating information sources are available instantly through the Internet, community resources, special interest organizations and television. Going further, information today is now searching for and finding individuals based on their previous search habits. This immediate access to volumes of information does have challenges as it is increasingly in unfiltered formats which question its reliability, validity and authenticity (ALA, 2000). Like media sources, text and visual information require a honed set of knowledge and skills to help determine the validity of this information and how to use it effectively.

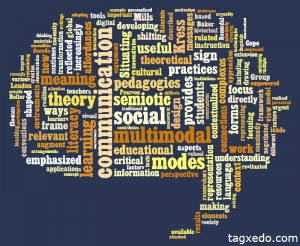

From these examples and many other aspects of digital technologies, comes the need to expand the traditional definition of literacy beyond text and numbers to a whole new agenda of multi-literacies including visual, media, digital, computer and information literacies.

Background

Post-secondary institutes invest large sums of money in information technology to support both teaching to meet the needs of students and to enhance student technology knowledge and skills to develop the graduates that employers demand (Lewis, Coursol and Khan, 2001). Employers expect graduates to have current technology knowledge and skills to support them and to provide growth in the workplace (Wilkinson, 2006). Many employers expect their employees to be information literate and consider information literacy as important as communication skills (ILAC 2003). However, expectations around information technology use and the associated required skills are constantly changing as technology rapidly evolves.

Associated with the development and use of digital tools and technology is the development of specialized literacies that are growing and changing rapidly as technology changes. Traditionally, literacy referred to reading and writing, and like numeracy, these skills have never been optional to be a fully functional member of society (Jones-Kavalier and Flannigan, 2006). Since the computer revolution for example, computer and digital literacy have appeared and evolved, and are currently merging into a broader literacy called information literacy.

There are several types of technology related literacy discussed in the literature: computer, digital, information, visual and media. Computer literacy deals with the use of computers and related technologies. Digital literacy goes beyond basic computer skills and deals with the use of information with digital technologies (Media Awareness Network, 2010). Information literacy deals with abilities to analyze information to support decision making. Some researchers (as reported by Higntte, Margavio and Margavio 2009) argue that the concept of computer literacy is dated and that we should focus on information literacy. Visual literacy as defined by Felten (2008), p. 60) “involves the ability to understand, produce and use culturally significant images, objects and visual actions”. Media literacy deals with critically analyzing messages that people watch, hear and read.

All of these different literacies are important; however this essay will focus on information and media literacy skills as they play a key role that supports workforces competing in the global economy (Finn, 2004). In addition, the Media Awareness Network (2010) reported in 2010 that Canada has fallen behind many countries in developing our digital economy. They also state that Canada has not made digital literacy a cornerstone of our digital economy strategy like some of our competitors have such as the UK, Australia, New Zealand and the US.

Information literacy stems from the need to find and use appropriate information, thus it has a cornerstone in library science. With the development of information and communications technologies over the last 20 years, information and library science have evolved to incorporate these technologies as tools to help find and process information.

Media literacy stems from the need to critically evaluate different forms of media and to effectively create content and communicate it through various forms, thus it has a cornerstone in media studies, mass communication, journalism and education. In post-secondary education then, media literacy is taught through either media or education lenses.

Media and Information Literacy Standards

In the US, media literacy is defined as: “ ….the ability to access, analyze, evaluate and communicate messages in a variety of forms” Aufderheide, 1993, p. xx) and “a media literate person … can decode, evaluate, analyze and produce both print and electronic media” (Aufderheide, 1997, p. 79). Conceptualizations of media literacy include: “a) Media are constructed and construct reality; (b) Media have commercial implications, (c) Media have ideological and political implications; (d) Form and content are related in each medium, each of which has unique aesthetics, codes and conventions; and (e) Receivers negotiate meaning in media” (Aufderheide, 1997, p. 80). Canada has very similar conceptualizations with eight key concepts for media literacy (AML, 2011)

In the US, there are no direct media standards for post-secondary education, however there are two indirect media standards. The Accrediting Council for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (ACEJMC) is responsible “for the evaluation of professional journalism and mass communications programs in colleges and universities” (ACEJMC, 2004, para. 1). These standards are aimed at practitioners. The second indirect standard is with the National Communication Association (NCA) that has media standards and competencies developed for K-12 education, thus these standards are aimed at students (Christ, 2004).

There are many different definitions of information literacy in the literature. The American Library Association (ALA) defines literacy as a set of abilities requiring individuals to “recognize when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information” (ALA, 1989). In addition, the ALA describes an information literate person with the ability to: (1) determine the information needed, (2) access the information needed, (3) evaluate the information and its sources critically, (4) incorporate and use information effectively and (5) understand the economic, legal, ethical and social issues associated with accessing and using information.

Information literacy standards for post-secondary education are well documented by the Association of College and Research Libraries a division of the American Library Association (ALA, 2000). These higher education standards are designed to articulate with K-12 literacy competencies to provide a continuum of expectations for students of all ages and levels. The standards support information literacy abilities as follows: five standards, each with several performance indicators and these in turn supported with outcomes.

Similarly in the United Kingdom, the Society of College, National and University Libraries (SCONUL) have developed standards, or information literacy pillars. Seven pillars of information literacy were developed in 1999 and were recently updated and expanded in 2011 due to a broader range of terminology and concepts included in information literacy today (SCONUL, 2011). SCONUL currently defines information literacy broader than in the North American context as it includes digital, visual, media, academic literacy in addition to the traditional aspects of information literacy. The seven key pillar terms are: identify, scope, plan, gather, evaluate, manage and present.

Jarson (2010) provides a concise summary of issues and sources of information for information literacy in higher education. Included in these sources are definitions and standards, curriculum models, plans and instruction, embedded librarianship, assignment design, assessments, multi-institutional projects and toolkits.

Post-Secondary Education

Media Literacy

Mihailidis (2008) describes the state of media literacy in US higher education as tenuous, inconsistent, marginal and often contested resulting in intangible and incoherent media literacy learning outcomes. He blames this on three general trends: late introduction, thus the US lags behind other major English speaking countries, second, most initiatives related to media literacy and scholarship has been developed for K-12 education and third, the US definition of media literacy is based on broad and figurative terminology.

Several scholars (as reported by Mihailidis, 2008), have connected the need for media literacy with civic processes, citizenship and democratic rights. Masterman (1985 and 1998) described the need for media literacy to support participatory democracy for citizens to have power, make reasonable decisions and to become change agents. He also encourages students to strengthen their values and beliefs about democracy through increased media literacy. Further, Mihailidis (2008) encourages citizens to pursue lifelong learning supported with media literacy to find and use relevant information related to their lives, community and country.

Holistic media education as described by Duran, Yousman, Walsh and Longshore (2008) takes media literacy beyond the traditional textural form of critically analysing messages, to a contextual form that deals with production and consumption of media. This involves asking questions such as: why are messages produced, who produces the messages and under what conditions and constraints were they produced (Jhally and Lewis, 1998).

In summary, the literature seems to agree that media literacy education stops for the most part at the end of a student’s K-12 journey. It only continues in post-secondary for students who are enrolled in media studies, mass communication, journalism and education programs.

Information Literacy

Information literacy skills are important across most disciplines of post-secondary education. Information literacy is critical for any student gathering information or conducting research. A study in the US in 2009 revealed that college students almost always turned to Google or Wikipedia for everyday research, but for course related research they used course readings and Google first. They also used library resources; online databases, for course related research but underutilized librarians; only about 20% used librarians. The study concludes that in general, college students “dial down the aperture of all the different resources that are available to them in the digital age” (Head and Eisenberg, 2009, p. 3). These results are supported by research summarized by (Van de Vord, 2010) that indicates current post-secondary students lack critical thinking skills needed to evaluate information accessed and thus do not have the information literacy skills to be successful in the twenty first century.

Discussion

There is a connection between information and media literacy. The critical evaluation and thinking skills developed to find and use appropriate information can also be used to critically analyze messages. Van de Vord, (2010) found a significant positive correlation between information and media literacy skills of distance students taking on-line courses. Thus critical thinking skills are the key to student media and information literacy skills. To build on the media and information literacy skills of students transitioning from K-12, post-secondary institutes need to apply critical thinking skills to situations in the curriculum that allow students to increase their media and information skills. This can and is being done through specific courses to address these literacies or integrated throughout the courses in programs. The Information Literacy Across the Curriculum Continuous Improvement Team recommends the course integrated approach ILAC, 2003). General education outcomes can be easily expanded to include media and information literacy by broadening the interpretation of critical thinking skills.

References

Accrediting Council for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication. (2004). Accrediting standards. Retrieved November 24, 2011 from http://www2.ku.edu/~acejmc/PROGRAM/STANDARDS.SHTML

American Library Association (1989). Presidential Committee on Information Literacy: Final Report. Retrieved November 26, 2011 from: http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/acrl/publications/whitepapers/presidential.cfm

American Library Association (2000). The information literacy competency standards for higher education. Association of College and Research Libraries. Retrieved October 15, 2011 from: http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/acrl/standards/informationliteracycompetency.cfm

AML (2011) What is media literacy. Retrieved November 22, 2011 from http://www.aml.ca/whatis/

Aufderheide, P. (Ed.). (1993). Media literacy: A report of the National Leadership Conference on Media Literacy. Aspen, CO: Aspen Institute. Retrieved November 24, 2011 from http://www.medialit.org/reading-room/aspen-institute-report-national-leadership-conference-media-literacy

Aufderheide, P. (1997). Media literacy: From a report of the National Leadership Conference on Media Literacy. In R. Kubey (Ed.), Media literacy in the information age (pp. 79-86). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Christ, W. G. (2004). Assessment, media literacy standards, and higher education. American Behavioral Scientist, 48, 92–96.

Duran, R., Yousman, B., Walsh, K., and Longshore, M. (2008). Holistic Media Education: An Assessment of the Effectiveness of a College Course in Media Literacy. Communication Quarterly, 56 (1), 49-68.

Felton, P. (2008). Visual Literacy. Change. November/December 2008. Retrieved November 24, 2011 from http://www.changemag.org/Archives/Back%20Issues/November-December%202008/abstract-visual-literacy.html

Finn, C., (2004). The mandate of digital literacy. Technology and Learning Magazine. August 1, 2004. Retrieved November 24, 2011 from: http://www.techlearning.com/article/2602

Head, A.J., and Eisenberg, M. (2009). How College Students Seek Information in the Digital Ages. Project Information Literacy Progress Report. The Information School, University of Washington. Retrieved November 24, 2011 from: http://projectinfolit.org/pdfs/PIL_Fall2009_Year1Report_12_2009.pdf

Higntte, M., Margavio, T., & Margavio, G. (2009). Information literacy assessment: moving beyond computer literacy. College Student Journal, 43(3), 812-821. Retrieved from Education Research Complete database.

Information Literacy Across the Curriculum (2003). Information literacy across the curriculum action plan. Retrieved November 24, 2011 from: http://www.cod.edu/library/services/faculty/infolit/actionplan.pdf

Jarson, J. (2010). Information Literacy and Higher Education: A Toolkit for Curricular Integration. College and Research Libraries News. 71 (no10), 534-538. Retrieved November 24, 2011 from: http://crln.acrl.org/content/71/10/534.full.pdf+html

Jhally, S., & Lewis, J. (1998). The struggle over media literacy. Journal of Communication, 48, 109–120. Retrieved November 24, 2011 from: http://myweb.wwu.edu/karlberg/444/readings/struggle.pdf

Jones-Kavalier, B., and Flannigan, S. (2006) Connecting the Digital Dots: literacy of the 21st century. EDUCAUSE Quarterly, 29 (2). Retrieved November 24, 2011 from: http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/eqm0621.pdf

Lewis, J., Coursol, D., and Khan, L. (2001). College students @tech.edu: Study of comfort and the use of technology [Electronic version]. Journal of College Student Development, 42(6), 625-632.

Masterman, L. (1985). Teaching the media. London, UK: Routledge.

Masterman, L. (1998). Forward: The media education revolution. In Hart, A. (Ed.), Teaching the media: International perspectives, (p. xi). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Mihailidis, P. (2008). Are We Speaking the Same Language? Assessing the State of Media Literacy in U.S. Higher Education. Simile, 8 (4), 1-14.

Media Awareness Network (2010). Digital Literacy in Canada: From Inclusion to Transformation. A submission to the digital economy Strategy Consultation. Available at: http://www.media-awareness.ca/english/corporate/media_kit/digital_literacy_paper_pdf/digitalliteracypaper.pdf

Mitchell, W. J. (1995). Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

SCONUL (2011). The SCONUL seven pillars of Information Literacy: Core model for higher education. SCONUL working group on information literacy. ). Retrieved November 24, 2011 from: http://www.sconul.ac.uk/groups/information_literacy/publications/coremodel.pdf

Oblinger, D. G., & Oblinger, J. L. (2005). Educating the Net Generation. Boulder, CO: Educause. Retrieved November 24, 2011 from: http://www.educause.edu/educatingthenetgen

Van de Vord, R. (2010). Distance students and online research: promoting information literacy through media literacy. Internet and Higher Education, 13, 170-175.

Wilkinson, K. (2006). Students Computer Literacy: Perception Versus Reality. Delta Pi Epsilon Journal, 48(2), 108-120. Retrieved from Education Research Complete database.

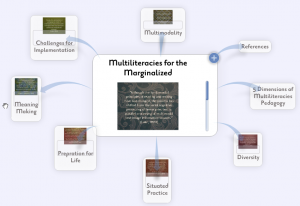

In the digital space of flows, where ideas collide and coincide across a fluid state of chaos within data streams across the nodes of our network society, there exists a new level of creativity impacting global society. Like sparks of creative flows across the synaptic pathways of the brain, media-rich stories are being created across the internet uniting author and reader into a combined and seemingly paradoxical role of both producer and consumer. In this creative space, Web 2.0 digital stories move beyond the linear construction of the printed book into a more unpredictable, open-ended, participatory, hyperlinked and flexible form of media. Alexander and Levine (2008) describe the Web 2.0 digital story as a new form of storytelling based on microcontent and social media. Microcontent is self-contained, embedded and in continual flux, whether it’s a blog post, a wiki edit, online video or podcast. This new space for creative production and consumption is easily accessible through keywords and exists in a virtual place of distributed discussion (Alexander & Levine, 2008). Web 2.0 stories are narratives constructed in a participatory space, buttressed by social media, and enabled with flexibility to enable consumers to leave and return through hyperlinking. Similar to oral traditions, digital stories are structured around people, yet beyond both oral and print methods, rich media provides a multimodal experience. This hearkens to the theories of the

In the digital space of flows, where ideas collide and coincide across a fluid state of chaos within data streams across the nodes of our network society, there exists a new level of creativity impacting global society. Like sparks of creative flows across the synaptic pathways of the brain, media-rich stories are being created across the internet uniting author and reader into a combined and seemingly paradoxical role of both producer and consumer. In this creative space, Web 2.0 digital stories move beyond the linear construction of the printed book into a more unpredictable, open-ended, participatory, hyperlinked and flexible form of media. Alexander and Levine (2008) describe the Web 2.0 digital story as a new form of storytelling based on microcontent and social media. Microcontent is self-contained, embedded and in continual flux, whether it’s a blog post, a wiki edit, online video or podcast. This new space for creative production and consumption is easily accessible through keywords and exists in a virtual place of distributed discussion (Alexander & Levine, 2008). Web 2.0 stories are narratives constructed in a participatory space, buttressed by social media, and enabled with flexibility to enable consumers to leave and return through hyperlinking. Similar to oral traditions, digital stories are structured around people, yet beyond both oral and print methods, rich media provides a multimodal experience. This hearkens to the theories of the

Commentary #3 – Alexander’s Web 2.0: A New Wave of Innovation for Teaching and Learning? and Web 2.0: Storytelling, Emergence of a New Genre

Alexander (2008) defines the Web 2.0 as a way of creating Web pages focusing on microcontent and social connections between people, which exemplify that digital content can be copied, moved, altered, remixed, and linked, based on the needs, interests and abilities of users. Microcontent refers to small bits of data (usually, text or visuals) that are posted on a Web page where users can respond to the data through conversation, including their approval, or disapproval of it. According to Solomon and Schrum (2007), Web 2.0 has “morphed from static HTML pages where readers could find and copy information to interactive services, where visitors can create and post information.” They include that Web 2.0 tools transition users from isolation to interconnectedness. Alexander adds that Web 2.0 platforms are organized around people and their interests, instead of hierarchies and directory trees. Solomon and Shrum list some features of the transition from the old Web 1.0 to the new semantic Web 2.0 as Web-based, collaborative, online, free, open source, as well as having shared content and multiple collaborators. Schools and teachers are striving, and sometimes struggling, to teach students with Web 2.0 tools in their classrooms in an attempt to remain current and give students every technological advantage possible. Twenty-first century skills, including Web 2.0 tools, are proving difficult to teach as schools struggle to keep up with technological innovation. Web 2.0 has become a part of our everyday lives as we use the technology to interact and connect with those around us, which in turn, is making our online interactions more human.

The New London Group (1996) noted that the Web needed to overcome regional and ethnical bounds, creating a community of learners. Web 2.0 tools currently accomplish this community through common literacy, reflection, and feedback mostly from anonymous visitors. Solomon and Schrum (2007) suggest 21st century literacy skills include Web 2.0 use in the teaching of content areas like global awareness, financial literacy and health awareness. They go on to expand on how today’s students are surrounded by Web 2.0 tools; schools need to teach students how to use these tools to acquire new skills, not just play with them. Today’s kids are surrounded by websites and Smartphone apps such as Facebook, MySpace, Twitter and Wikipedia. They use these Web 2.0 tools to socialize with friends, follow the news, research school projects, and communicate with each other. These programs are constantly changing as the users mature and new technologies become available. Evidence of how Web 2.0 creates a community has been observed lately as it has assisted in political uprisings and social change. As more people and businesses find ways to apply Web 2.0 tools they become solidified parts of our technological society.

Web 2.0 is continually evolving as the collective users overcome hurdles such as online information storage, security issues (Solomon and Schrum, 2007), computer crime, and low publishing standards (Alexander and Levine, 2008). As with any online platform, there are some inequalities among users and programs. Bates and Poole (2003) address these inequalities in technology through their SECTIONS framework. They explore how each portion of their framework (Students, Ease of Use, Cost, Teaching and Learning, Interaction and Interactivity, Organization, Novelty and Speed) needs addressing before educators can effectively use them in their teaching. Some Web 2.0 tools are not appropriate for academia, as Alexander (2006) suggests, and institutions often block sites, as they feel students cannot use the tools effectively, without distraction. These reasons may be why some educators are reluctant to use Web 2.0 tools at all in their classrooms. Solomon and Schrum (2007) argue that these tools need to be fostered as they, “promote creativity, collaboration, and communication, and they dovetail the learning methods in which these skills play a part.” They go on to support their stand by adding, “The new way is collaborative, with information shared, discussed, refined with others, and understood deeply.” Twenty-first century students are immersed in technology at home, but often suffer a lack of it at school, where they are forced to write with pen and paper without links or visuals. Many students may become bored, uncreative, and complacent because of little or archaic technology in their classes. These are all real issues that educators and students face in these uncertain technological times. Ironically, Web 2.0 tools can help us discuss these issues in education and we can collectively find solutions to the problems at hand.

Web 2.0 may not be here to stay, but many aspects of it are making technology more human in its features. They way humans connect with each other, explore their surroundings, approach tasks and even process information are becoming mirrored in technology use. The more human-like technology becomes, the more apt we are to use it as a society. Web 2.0 is no exception. As we catalogue, tag, and share information we become a part of the technology that we use. I echo Alexander’s (2008) closing remarks where he invites educators to, “give Web 2.0 storytelling a try and see what happens.” You will never know what is behind a closed door until you step over the threshold.

References

Alexander, B. (2006). Web 2.0: A new wave of innovation for innovation for teaching and learning. Educause Review. March-April, 2008.

Alexander, B. (2009). Web 2.0 and emergent multiliteracies, theory into practice. National Institute for Technology and Liberal Education. 47(2). p. 150-160.

Alexander, B. & Levine, A. (2008). Web 2.0: Storytelling, emergence of a new game. Educause Review. November-December, 2008.

Bates, A.W. & Poole, G. (2003). Effective teaching with technology in higher education: Foundations for Success. New York. Wiley, John and Sons Incorporated. P. 75-105.

Bolter, J.D. (2001). Writing Space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print. Mahway, NJ. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Solomon, G. & Schrum, L. (2007). Web 2.0: New tools, new schools. International Society for Technology in Education. Washington, DC.

The New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review. 66(1). p. 60-92.