Posts from — November 2009

Multi-literacy and assessment

Commentary # 3, Cecilia Tagliapietra

Along this course, we’ve discussed the “creation” or discovery of text and how it has transformed throughout the ages; providing mankind a way of expressing thoughts and feelings. In this third and last commentary, I’d like to discuss how we’ve become literate in different areas and how literacy, as text, has also been transformed to fit new manifestations of text. I’d also like to touch upon the challenges we face as teachers, to assess and impulse the development of these competencies or literacies.

As text has transformed spaces and human consciousness (Ong, 1982, p. 78), we’ve also changed the meaning of the term literacy, integrating not only the focus on text as the main aspect of it, but also the representations, and methods in which text is manifests, as well as the meaning given or understood according to different contexts. The New London Group (1996) has introduced the term “multiliteracies” for the “burgeoning variety of text forms associated with information and multimedia technologies” (p. 60). From this understanding and meaning, we can identify different literacy abilities or competencies. The two most important types of literacies we’ll narrow down to are: digital literacy and information literacy.

Dobson and Willinsky (2009) assertively express that “digital literacy constitutes an entirely new medium for reading and writing, it is but a further extension of what writing first made of language” (referring to the transformation of human consciousness, (Ong, 1982, p. 78)). These authors consider digital literacy an evolution that integrates and expands on previous literacy concepts and processes, as Bolter expresses “Each medium seems to follow this pattern of borrowing and refashioning other media” (Bolter, 2001, pg. 25). With digital literacy, we can clearly identify previous structures and elements shaping into new, globalized and closely related contexts.

Digital technologies have recently forced us to change and expand what we understand as literacy. Being digitally literate is being able to look for, understand, evaluate and create information within the different manifestations of text in non-physical or digital media. Information literacy is also closely linked to the concept of digital literacy. According to the American Association of School Librarians (1998), an information literate, should: access information efficiently and effectively, evaluate information critically and competently, use the information accurately and creatively. We can clearly see an interrelationship between the concepts of these literacies; they both rely on an interpretation of text and an effective use of this interpretation. The development of critical thinking skills is also closely related to these concepts and the ability to use information (and text) creatively and accurately.

The use of these new literacies has also changed (and continues to do so) the way we communicate and learn; we constantly interact with multimedia and rapidly changing information. Even relationships and authority “positions” are restructured, as consumers also become producers of knowledge and text. With the introduction and use of these new literacies, education has somehow been “forced” to integrate these competencies into the curriculum and, most importantly, into the daily teaching and learning phenomena.

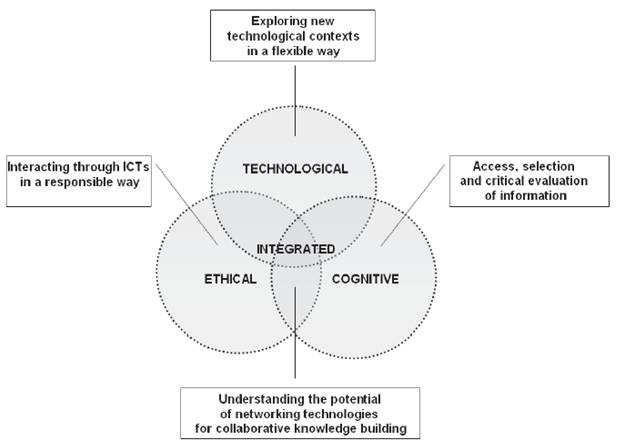

As teachers, we are not only required to facilitate learning in math, science, etc.; we are also required to facilitate and encourage the development of these literacies as well as critical thinking skills. Teaching and assessing these abilities is no easy task, as it’s not always manifested in a concrete product. Calvani and co-authors (Calvani, et.al, 2008), propose an integral assessment for these new competencies, involving the technological, cognitive and ethical aspects of the literacies (See Figure 1). In order to assess, we must initially transform our daily practices to integrate these abilities for our students and for ourselves. Being literate (in the “normal” concept) is not an option anymore. We are bombarded with and have access to massive amounts of information which we need to disseminate, analyze and choose carefully. Digital and information literacies are needed competencies to successfully understand and interpret the globalized context and be able to integrate ourselves into it.

Learning (ourselves) and teaching others to be literate or multi-literate is an important task at hand. Tapscott (1997) has mentioned that the NET generation is multitasker, digitally competent and a creative learner. As educators and learning facilitators, we also need to integrate and develop these competencies within our contexts.

Literacy has transformed and integrated different concepts and competencies, what it will mean or integrate in five years or a decade?

Figure 1: Digital Competence Framework (Calvani, et.al, 2008, pg. 187)

References:

American Association of School Librarians/ Association for Educational Communications and Technology. (1998) Information literacy standards for student learning. Standards and Indicators. Retrieved November 28, 2009 from: http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/aasl/guidelinesandstandards/informationpower/InformationLiteracyStandards_final.pdf

Calvani, A. et. al (2008) Models and Instruments for Assessing Digital Competence at School. Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society. Vol. 4, n. 3, September 2008 (pp. 183 – 193). Retrieved November 28, 2009 from: http://je-lks.maieutiche.economia.unitn.it/en/08_03/ap_calvani.pdf

Dobson and Willinsky’s (2009) chapter “Digital Literacy.” Submitted draft version of a chapter for The Cambridge Handbook on Literacy.

New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60-92. Retrieved, November 28, 2009, from http://newlearningonline.com/~newlearn/wp-content/uploads/2009/03/multiliteracies_her_vol_66_1996.pdf

Tapscott, Don. Growing Up Digital: The Rise of the Net Generation, Retrieved November 28, 2009 from: http://www.ncsu.edu/meridian/jan98/feat_6/digital.html

November 29, 2009 1 Comment

Social Tagging

Third Commentary by Dilip Verma

Social Tagging

Many popular web based applications are described as belonging to the Web 2.0. Alexander (2008) suggests that what defines Web 2.0 software is that it permits social networking, microcontent and social filtering. Users participate in the Web 2.0 by making small contributions that they link to the works of other contributors to form part of a participative discourse based on sharing. In social filtering, “creators comment on other’s creations, allowing readers to triangulate between primary and secondary sources.” (Alexander, 2008). One of the offspring of this new cooperative form of literacy is the creation of Folksonomies.

Folksonomies are user-defined vocabularies used as metadata for the classification of Web 2.0 content. Users and producers voluntarily add key words to their microcontent. There are no restrictions on these tags, though programs often make suggestions by showing the most commonly previously used tags. Folksonomies (also known as ethnoclassification) represent an important break with the traditional forms of information classification systems. This technology is still in its infancy; presently it is used for the categorizing of photos in Flickr, of Web pages in Del.icio.us and of blog content in Technorati. However, its use is sure to spread as the Web 2.0 gains popularity.

Berner- Lee, designed the Web to allow people to share documents using standard protocols. His proposal for the Semantic Web (see video) is that raw data should now be made shareable both between web programs and between users. At the moment social tagging is program specific. There is no reason to assume that it will or should remain this way. For tags to be readable by different programs, they will require a common structure. A system whereby tags can be shared and analyzed across applications is possible by creating an ontology of tags. This ontology will merely be a standard of metadata that records more than just the tag word applied to an object. Gruber (2007) proposes a structure for the metadata including information on the tag, the tagger, and the source. In this way tags will be transferable and searchable across the Web, making them a much more powerful technology.

Standard classification systems are structured from the top down. Professionals carefully break down knowledge into categories and build a vocabulary, which can then be used to hierarchically categorize information. Traditionally, categorizing is a labor-intensive, highly skilled process reserved for professionals. It also requires users to buy into a culturally defined way of knowing. Social tagging is the creation of metadata not by professionals (e.g. librarians or catalogers), but by the authors and users of microcontent. The tags are used both as an individual form of organizing as well as for sharing the microcontent within a community (Mathes, 2004).

Weinberger (2007) divides organizational systems into three orders, defining the third order as a system where information is digital and metadata is added by users rather than professionals. Apart from the physical advantages of storing information digitally, the author sees that this change in the creation of metadata will “undermine some of our most deeply ingrained ways of thinking about the world and our knowledge of it.” Weinberger (2007) sees tagging as empowering, as it lets users define meaning by forming their own relationships rather than having categories imposed upon them. “It is changing how we think the world itself is organized and -perhaps more important- who we think has the authority to tell us so.” (Weinberger,2007, ¶ 48). Mathes notes that “the users of a system are negotiating the meaning of the terms in the Folksonomy, whether purposefully or not, through their individual choices of tags to describe documents for themselves” (2004, ¶ 46). In Folksonomies, the creation of meaning lies firmly on the shoulders of the user.

The interesting thing about social tagging is that a consensus of meaning is naturally formed. “As contributors tag, they have access to tags from other readers, which often influence their own choice of tags” (Alexander, 2008, p. 154). Udell notes that “the real power emerges when you expand the scope to include all items, from all users, that match your tag. Again, that view might not be what you expected. In that case, you can adapt to the group norm, keep your tag in a bid to influence the group norm, or both” (2004, ¶ 5). Folksonomies are organic as they develop naturally through voluntary contributions. Traditionally, society defines the “set of appropriate criteria” by which things may be categorized (Weinberger, 2007, ¶ 6). But Folksonomies should allow us “to get rid of the idea that there’s a best way of organizing the world” (Weinberger, 2007, ¶ 7).

However, Boyd raises some concerns about who is forming this consensus and its influence on power relations. The author notes that “most of the people tagging things have some form of shared cultural understandings” (2005, ¶ 3) and that these people are ” very homogenous” (2005, ¶ 3). The author adds that “we must think through issues of legitimacy and power. How are our collective choices enforcing hegemonic uses of language that may marginalize?” (2005, ¶ 7). At the moment the use of tags is restricted to a small homogenous group. This is representative of the wider problem of the globalizing influence of a web dominated by “a celebration of the “Californian ideology”” (Boshier & Chia, 1999). The consensus formed in Folksonomies will be representative of only a small sector of the population. To address this requires providing access and a voice in the Web 2.0 discourse to minorities. If user defined tags become the standard for metadata on the Web 2.0, it is important that all groups take part in the forming of the consensus. Without access for marginalized communities, Folksonomies will not achieve their true liberating potential.

References

Alexander, B. (2008). Web 2.0 and Emergent Multiliteracies. Theory into Practice, 47(2), 150-160. Retrieved November 20, 2009 from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00405840801992371

Boyd, D. (2005). Issues of Culture in Ethnoclassification/Folksonomy. Retrieved November 26, 2009, from Corante Web Site: http://www.corante.com/cgi-bin/mt/teriore.fcgi/1829

Boshier, R. & Chia, M. O.(1999) Discursive Constructions Of Web Learning And Education: “World Wide” And “Open?” Proceedings of the Pan-Commonwealth Forum on Open Learning Retrieved November 15 from http://www.col.org/forum/PCFpapers/PostWork/boshier.pdf

Gruber, T. (2007). Ontology of Folksonomy: A Mash-up of Apples and Oranges. Int’l Journal on Semantic Web & Information Systems, 3(2). Retrieved November 27, 2009 from http://tomgruber.org/writing/ontology-of-folksonomy.htm

Mathes, A. (2004). Folksonomies-Cooperative Classification and Communication Through Shared Metadata. Retrieved November 26, 2009 from http://www.adammathes.com/academic/computer-mediated-communication/folksonomies.html

Udell, J. (2004). Collaborative Knowledge Gardening. Retrieved November 25, 2009, from InfoWorld Web Site: http://www.infoworld.com/d/developer-world/collaborative-knowledge-gardening-020

Weinberger, D. (2007). Everything Is Miscellaneous: The Power of the New Digital Disorder. New York: Times Books. Retrieved November 26, 2009 from http://www.everythingismiscellaneous.com/wp-content/samples/eim-sample-chapter1.html

November 29, 2009 3 Comments

Major Project – E-Type: The Visual Language of Typography

Typography shapes language and makes the written word ‘visible’. With this in mind I felt that it was essential to be cognizant about how my major project would be presented in its final format. In support of my research on type in digital spaces, I created an ‘electronic book’ of sorts, using Adobe InDesign CS4 and Adobe Acrobat 9. Essentially I took a traditionally written essay and then modified and designed it to fit a digital space. The end result was supposed to be an interactive .swf file but I ran into too many technical difficulties. So what resulted was an interactive PDF book.

The e-book was designed to have a sequential structure, supported by a table of contents, headings and page numbering – much like that of a traditional printed book. However, the e-book extends beyond the boundaries of the ‘page’ as the user, through hyperlinks, can explore multiple and diverse worlds of information located online. Bolter (2001) uses the term remediation to describe how new technologies refashion the old. Ultimately, this project pays homage to the printed book, but maintains its own unique characteristics specific to the electronic world.

To view the book click on the PDF Book link below. The file should open in a web browser. If by chance, you need Acrobat Reader to view the file and you do not have the latest version you can download it here: http://get.adobe.com/reader/

You can navigate through the document using the arrows in the top navigation bar of the document window. Alternatively you can jump to specific content by using the associated Bookmarks (located in left-hand navigation bar) or by clicking on the chapter links in the Table of Contents. As you navigate through the pages you will be prompted to visit websites as well as complete short activities. An accessible Word version of the essay is also available below.

References

Bolter, J.D. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

To view my project, click on the following links:

November 29, 2009 4 Comments

Commentary # 3

Is Web 2.0 Selling out the Younger Generation?

Commentary # 3

By David Berljawsky

Submitted to Prof. Miller

Nov 29, 2009

There is one underlying theme that involves technology and text education that I need to touch upon. Are we sabotaging the upcoming generation with the way that we teach technology? Or is it the opposite and we are actually giving them the proper tools to succeed? It is possible that in the shift to modern web 2.0 technologies we are neglecting to educate about the simplest things that we take for granted? This can include key knowledge’s such as social skills, communication and even basic literacy? Students are engaged in the web 2.0 process like never before. These technologies are creative based and offer the user a newfound ability to edit and modify information to fit into their respective wants and needs. According to Alexander “In American K-12 education, students increasingly accept these kinds of technology-driven information structures and the literacies that flow from them (Alexander, P.2).” To me this quote acts as a double edged sword. Students are engaged in the new literacies (web 2.0) like never before, but are these new literacies appropriate and conducive to meeting proper educational standards? Or do they simply aid in creating an individualist society that is lacking a sense of community? This paper will examine some of the positive and negative aspects that occur when Web 2.0 is taught without providing the proper scaffolding. This commentary will examine its potential consequences both socially and educationally.

One needs to examine the benefits of these technologies and understand their positive influences before one can criticize them. According to the New London Group, in its article “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures, “As a result, the meaning of literacy pedagogy has changed. Local diversity and global connectedness mean not only that there can be no standard; they also mean that the most important skill students need to learn is to negotiate regional; ethnic, or class-based dialects… (New London, P.8).” This melds together education, literacy and even community in a newfound manner. It is a mix-up or mash-up of sorts. Students are required, due to the changing landscape of the world and technology to concentrate on learning communication skills with other cultures in an online environment. One would assume that this is a positive and worthwhile endeavour to achieve towards. However, this can increase the creation of a more macro centered community. This will only increase the affects of globalization and prevent local communities from prospering and expressing themselves.

One benefit in using these technologies is that students are likely engaged in the process and the multicultural aspirations of our society. These are promoted like never before. However I can think of an obvious negative aspect. There is little actual social interaction. In Web 2.0 social interaction is promoted through websites that offer social networking in an online environment. This certainly does have its benefits. “Web 2.0’s lowered barrier to entry may influence a variety of cultural forms with powerful implications for education, from storytelling to classroom teaching to individual learning (Alexander, P.42).” What may occur is a socially constructed generational divide. Generation A’s perceived culturally appropriate way of communication (web 2.0) will conflict with the older generation who still use older technologies. This makes me think of an Orwellian future where we communicate entirely through electronic means, where physical interaction is seen as being against the norm. This is somewhat true already in our use of technologies such as Facebook and MySpace, where people communicate more through them then with old fashioned telephones. We are currently text electronically instead of talking with our own voices. Educators need to be aware of this paradigm shift and change their practices accordingly.

Another danger in using web 2.0 and modern computer technologies in the classroom occurs when the educators do not educate the students about why they are learning these new technologies. Simply providing the student with a blog or a wiki and expecting them to formulate appropriate arguments and concepts is unlikely to happen without the proper scaffolding. “They don’t link ideas,” the teacher says, “They just write one thing, and then they write another one, and they don’t develop the relationships between them (Dobson & Willinsky, p.3).” This can be seen as a failure in the education system. Regardless of one views of technology use in the classroom it still remains an imperative process to educate students about the proper forms of literacy and writing. Without the proper knowledge and skills communication with older generations can be difficult, especially in the workplace.

There is an inherent danger in education that occurs when any form of technology becomes dominant. What is previously seen as integral and important becomes seen as archaic and becomes lost. Educators need to allow the younger generation to develop the multiliteracies and computer intelligence needed to proceed in their career paths without ignoring teaching the traditional educational foundations. That is a huge challenge. Educators need to accept that the younger generation has different forms of communications and multiliteracies and adjust accordingly. Both educators and students need to respect the knowledge being transmitted. “We have our unique ways of knowing, teaching and learning which are firmly grounded in the context of our ways of being. And yet we are thrust into the clothes of another system designed for different bodies, and we are fed ideologies which serve the interests of other peoples (Donovan, P.96).”

If we do not accept this evolution and work on actually decreasing the social and communicative gap between the generations the divide will only be extended. The generations will have trouble relating with the each other both socially and in the workplace. This might ultimately lead to both generations harbouring feeling of resentment because they feel that their leanings and ideologies are being put down and disvalued.

References

Alexander, B. (2008) “Web 2.0 and Emergent Multiliteracies.” Theory into practice. 47(2), 150-60. Retrieved, July 20, 2009, from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00405840801992371

Alexander, B. (2006) “Web 2.0: A new wave of innovation for teaching and learning?” Educause Review, 41(2), 34-44. Retrieved, April 5, 2008, from http://www.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ERM0621.pdf

New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60-92. Retrieved, August 15, 2009, from http://newlearningonline.com/~newlearn/wpcontent/uploads/2009/03/multiliteracies_her_vol_66_1996.pdf

Dobson, Teresa, & John Willinsky (2009). Digital Literacy. (OlsonD., TorranceN., Ed.). Cambridge Handbook on Literacy. http://pkp.sfu.ca/files/Digital%20Literacy.pdf [Book Chapter]

Donovan, Michael (2007). “Can Information Communication Technological Tools be Used to Suit Aboriginal Learning Pedagogies?” Published in “Information Technology and Indigenous People”. Editied by Dyson, Laurel. Hendriks, Max and Grant, Stephan. Idea Group. USA. 2007.

November 29, 2009 1 Comment

Classroom Community & Digital Storytelling

Using digital storytelling with my grade seven students has been a growing passion over the last few years. In particular, I’ve found that this medium not only hooks in reluctant writers but goes along way in building community amongst peers. Here is the link to my UBC Wiki page.

Drew

PS – Below are the two student examples I reference in my paper. I was unable to upload them on my Wiki page so I posted them here instead.

November 29, 2009 No Comments

Just a few links from social networking

http://www.diigo.com/user/david_b?tab=3

Just a few videos for fun.

I chose to use social networking for this assignment because I wanted to show a few videos that I’ve found this semester. I used diigo for my links. This is a very easy to use site. I’ve found that social networking works very well with students, I have used it before with high school and middle school aged students and have always been amazed at the quality of links that they find.

David.

November 29, 2009 No Comments

Hypermedia and Cybernetics: A Phenomenological Study

As with all other technologies, hypermedia technologies are inseparable from what is referred to in phenomenology as “lifeworlds”. The concept of a lifeworld is in part a development of an analysis of existence put forth by Martin Heidegger. Heidegger explains that our everyday experience is one in which we are concerned with the future and in which we encounter objects as parts of an interconnected complex of equipment related to our projects (Heidegger, 1962, p. 91-122). As such, we invariably encounter specific technologies only within a complex of equipment. Giving the example of a bridge, Heidegger notes that, “It does not just connect banks that are already there. The banks emerge as banks only as the bridge crosses the stream.” (Heidegger, 1993, p. 354). As a consequence of this connection between technologies and lifeworlds, new technologies bring about ecological changes to the lifeworlds, language, and cultural practices with which they are connected (Postman, 1993, p. 18). Hypermedia technologies are no exception.

To examine the kinds of changes brought about by hypermedia technologies it is important to examine the history not only of those technologies themselves but also of the lifeworlds in which they developed. Such a study will reveal that the development of hypermedia technologies involved an unlikely confluence of two subcultures. One of these subcultures belonged to the United States military-industrial-academic complex during World War II and the Cold War, and the other was part of the American counterculture movement of the 1960s.

Many developments in hypermedia can trace their origins back to the work of Norbert Wiener. During World War II, Wiener conducted research for the US military concerning how to aim anti-aircraft guns. The problem was that modern planes moved so fast that it was necessary for anti-aircraft gunners to aim their guns not at where the plane was when they fired the gun but where it would be some time after they fired. Where they needed to aim depended on the speed and course of the plane. In the course of his research into this problem, Wiener decided to treat the gunners and the gun as a single system. This led to his development of a multidisciplinary approach that he called “cybernetics”, which studied self-regulating systems and used the operations of computers as a model for these systems (Turner, 2006, p. 20-21).

This approach was first applied to the development of hypermedia in an article written by one of Norbert Wiener’s former colleges, Vannevar Bush. Bush had been responsible for instigating and running the National Defence Research Committee (which later became the Office of Scientific Research and Development), an organization responsible for government funding of military research by private contractors. Following his experiences in military research, Bush wrote an article in the Atlantic Monthly addressing the question of how scientists would be able to cope with growing specialization and how they would collate an overwhelming amount of research (Bush, 1945). Bush imagined a device, which he later called the “Memex”, in which information such as books, records, and communications would be stored on microfilm. This information would be capable of being projected on screens, and the person who used the Memex would be able to create a complex system of “trails” connecting different parts of the stored information. By connecting documents into a non-hierarchical system of information, the Memex would to some extent embody the principles of cybernetics first imagined by Wiener.

Inspired by Bush’s idea of the Memex, researcher Douglas Engelbart believed that such a device could be used to augment the use of “symbolic structures” and thereby accurately represent and manipulate “conceptual structures” (Engelbart, 1962).This led him and his team at the Augmentation Research Center (ARC) to develop the “On-line system” (NLS), an ancestor of the personal computer which included a screen, QWERTY keyboard, and a mouse. With this system, users could manipulate text and connect elements of text with hyperlinks. While Engelbart envisioned this system as augmenting the intellect of the individual, he conceived the individual was part of a system, which he referred to as an H-LAM/T system (a trained human with language, artefacts, and methodology) (ibid., p. 11). Drawing upon the ideas of cybernetics, Engelbart saw the NLS itself as a self-regulatory system in which engineers collaborated and, as a consequence, improved the system, a process he called “bootstrapping” (Turner, 2006, p. 108).

The military-industrial-academic complex’s cybernetic research culture also led to the idea of an interconnected network of computers, a move that would be key in the development of the internet and hypermedia. First formulated by J.C.R. Licklider, this idea was later executed by Bob Taylor with the creation of ARPANET (named after the defence department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency). As a extension of systems such as the NLS, such a system was a self-regulating network for collaboration also inspired by the study of cybernetics.

The late 1960s to the early 1980s saw hypermedia’s development transformed from a project within the US military-industrial-academic complex to a vision animating the American counterculture movement. This may seem remarkable for several reasons. Movements related to the budding counterculture in the early 1960s generally adhered to a view that developments in technology, particularly in computer technology, had a dehumanizing effect and threatened the authentic life of the individual. Such movements were also hostile to the US military-industrial-academic complex that had developed computer technologies, generally opposing American foreign policy and especially American military involvement in Vietnam. Computer technologies were seen as part of the power structure of this complex and were again seen as part of an oppressive dehumanizing force (Turner, 2006, p. 28-29).

This negative view of computer technologies more or less continued to hold in the New Left movements largely centred on the East Coast of the United States. However, a contrasting view began to grow in the counterculture movement developing primarily in the West Coast. Unlike the New Left movement, the counterculture became disaffected with traditional methods of social change, such as staging protests and organizing unions. It was thought that these methods still belonged to the traditional systems of power and, if anything, compounded the problems caused by those systems. To effect real change, it was believed, a shift in consciousness was necessary (Turner, 2006, p. 35-36).

Rather than seeing technologies as necessarily dehumanizing, some in the counterculture took the view that technology would be part of the means by which people liberated themselves from stultifying traditions. One major influences on this view was Marshall McLuhan, who argued that electronic media would become an extension of the human nervous system and would result in a new form of tribal social organization that he called the “global village” (McLuhan, 1962). Another influence, perhaps even stronger, was Buckminster Fuller, who took the cybernetic view of the world as an information system and coupled it with the belief that technology could be used by designers to live a life of authentic self-efficiency (Turner, 2006, p. 55-58).

In the late 1960s, many in the counterculture movement sought to effect the change in consciousness and social organization that they wished to see by forming communes (Turner, 2006, p. 32). These communes would embody the view that it was not through political protest but through the expansion of consciousness and the use of technologies (such as Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes) that a true revolution would be brought about. To supply members of these communes and other wayfarers in the counterculture with the tools they needed to make these changes, Stewart Brand developed the Whole Earth Catalogue (WEC). The WEC provided lists of books, mechanical devices, and outdoor gear that were available through mail order for low prices. Subscribers were also encouraged to provide information on other items that would be listed in subsequent editions. The WEC was not a commercial catalogue in that it wasn’t possible to order items from the catalogue itself. It was rather a publication that listed various sources of information and technology from a variety of contributors. As Fred Turner argues (2006, p. 72-73), it was seen as a forum by means of which people from various different communities could collaborate.

Like many others in the counterculture movement, Stewart Brand immersed himself in cybernetics literature. Inspired by the connection he saw between cybernetics and the philosophy of Buckminster Fuller, Brand used the WEC to broker connections between ARC and the then flourishing counterculture (Turner, 2006, p. 109-10). In 1985, Stewart Brand and former commune member Larry Brilliant took the further step of uniting the two cultures and placed the WEC online in one of the first virtual communities, the Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link or “WELL”. The WELL included bulletin board forums, email, and web pages and grew from a source of tools for counterculture communes into a forum for discussion and collaboration of any kind. The design of the WELL was based on communal principles and cybernetic theory. It was intended to be a self-regulating, non-hierarchical system for collaboration. As Turner notes (2005), “Like the Catalog, the WELL became a forum within which geographically dispersed individuals could build a sense of nonhierarchical, collaborative community around their interactions” (p. 491).

This confluence of military-industrial-academic complex technologies and the countercultural communities who put those technologies to use would form the roots of other hypermedia technologies. The ferment of the two cultures in Silicon Valley would result in the further development of the internet—the early dependence on text being supplanted by the use of text, image, and sound, transforming hypertext into full hypermedia. The idea of a self-regulating, non-hierarchical network would moreover result in the creation of the collaborative, social-networking technologies commonly denoted as “Web 2.0”.

This brief survey of the history of hypermedia technologies has shown that the lifeworlds in which these technologies developed was one first imagined in the field of cybernetics. It is a lifeworld characterised by non-hierarchical, self-regulating systems and by the project of collaborating and sharing information. First of all, it is characterized by non-hierarchical organizations of individuals. Even though these technologies first developed in the hierarchical system of the military-industrial-academic complex, it grew within a subculture of collaboration among scientists and engineers (Turner, 2006, p. 18). Rather than being strictly regimented, prominent figures in this subculture – including Wiener, Bush, and Engelbart -voiced concern over the possible authoritarian abuse of these technologies (ibid., p. 23-24).

The lifeworld associated with hypermedia is also characterized by the non-hierarchical dissemination of information. Rather than belonging to traditional institutions consisting of authorities who distribute information to others directly, these technologies involve the spread of information across networks. Such information is modified by individuals within the networks through the use of hyperlinks and collaborative software such as wikis.

The structure of hypermedia itself is also arguably non-hierarchical (Bolter, 2001, p. 27-46). Hypertext, and by extension hypermedia, facilitates an organization of information that admits of many different readings. That is, it is possible for the reader to navigate links and follow what Bush called different “trails” of connected information. Printed text generally restricts reading to one trail or at least very few trails, and lends itself to the organization of information in a hierarchical pattern (volumes divided into books, which are divided into chapters, which are divided into paragraphs, et cetera).

It is clear that the advent of hypermedia has been accompanied by changes in hierarchical organizations in lifeworlds and practices. One obvious example would be the damage that has been sustained by newspapers and the music industry. The phenomenological view of technologies as connected to lifeworlds and practices would provide a more sophisticated view of this change than the technological determinist view that hypermedia itself has brought about changes in society and the instrumentalist view that the technologies are value neutral and that these changes have been brought about by choice alone (Chandler, 2002). It would rather suggest that hypermedia is connected to practices that largely preclude both the hierarchical dissemination of information and the institutions that are involved in such dissemination. As such, they cannot but threaten institutions such as the music industry and newspapers. As Postman (1993) observes, “When an old technology is assaulted by a new one, institutions are threatened” (p. 18).

Critics of hypermedia technologies, such as Andrew Keen (2007), have generally focussed on this threat to institutions, arguing that such a threat undermines traditions of rational inquiry and the production of quality media. To some degree such criticisms are an extension of a traditional critique of modernity made by authors such as Alan Bloom (1987) and Christopher Lasch (1979). This would suggest that such criticisms are rooted in more perennial issues concerning the place of tradition, culture, and authority in society, and is not likely that these issues will subside. However, it is also unlikely that there will be a return to a state of affairs before the inception of hypermedia. Even the most strident critics of “Web 2.0” technologies embrace certain aspects of it.

The lifeworld of hypermedia does not necessarily oppose traditional sources of expertise to the extent that the descendants of the fiercely anti-authoritarian counterculture may suggest, though. Advocates of Web 2.0 technologies often appeal to the “wisdom of crowds”, alluding the work of James Surowiecki (2005). Surowiecki offers the view that, under certain conditions, the aggregation of the choices of independent individuals results in a better decision than one made by a single expert. He is mainly concerned with economic decisions, offering his theory as a defence of free markets. Yet this theory also suggests a general epistemology, one which would contend that the aggregation of the beliefs of many independent individuals will generally be closer to the truth than the view of a single expert. In this sense, it is an epistemology modelled on the cybernetic view of self-regulating systems. If it is correct, knowledge would be the result of a cybernetic network of individuals rather than a hierarchical system in which knowledge is created by experts and filtered down to others.

The main problem with the “wisdom of crowds” epistemology as it stands is that it does not explain the development of knowledge in the sciences and the humanities. Knowledge of this kind doubtless requires collaboration, but in any domain of inquiry this collaboration still requires the individual mastery of methodologies and bodies of knowledge. It is not the result of mere negotiation among people with radically disparate perspectives. These methodologies and bodies of knowledge may change, of course, but a study of the history of sciences and humanities shows that this generally does not occur through the efforts of those who are generally ignorant of those methodologies and bodies of knowledge sharing their opinions and arriving at a consensus.

As a rule, individuals do not take the position of global skeptics, doubting everything that is not self-evident or that does not follow necessarily from what is self-evident. Even if people would like to think that they are skeptics of this sort, to offer reasons for being skeptical about any belief they will need to draw upon a host of other beliefs that they accept as true, and to do so they will tend to rely on sources of information that they consider authoritative (Wittgenstein, 1969). Examples of the “wisdom of crowds” will also be ones in which individuals each draw upon what they consider to be established knowledge, or at least established methods for obtaining knowledge. Consequently, the wisdom of crowds is parasitic upon other forms of wisdom.

Hypermedia technologies and the practices and lifeworld to which they belong do not necessarily commit us to the crude epistemology based on the “wisdom of crowds”. The culture of collaboration among scientists that first characterized the development of these technologies did not preclude the importance of individual expertise. Nor did it oppose all notions of hierarchy. For example, Engelbart (1962) imagined the H-LAM/T system as one in which there are hierarchies of processes, with higher executive processes governing lower ones.

The lifeworlds and practices associated with hypermedia will evidently continue to pose a challenge to traditional sources of knowledge. Educational institutions have remained somewhat unaffected by the hardships faced by the music industry and newspapers due to their connection with other institutions and practices such as accreditation. If this phenomenological study is correct, however, it is difficult to believe that they will remain unaffected as these technologies take deeper roots in our lifeworld and our cultural practices. There will continue to be a need for expertise, though, and the challenge will be to develop methods for recognizing expertise, both in the sense of providing standards for accrediting experts and in the sense of providing remuneration for expertise. As this concerns the structure of lifeworlds and practices themselves, it will require a further examination of those lifeworlds and practises and an investigation of ideas and values surrounding the nature of authority and of expertise.

References

Bloom, A. (1987). The closing of the American mind. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Bolter, J. D. (2001) Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print (2nd ed.). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bush, V. (1945). As we may think. Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/194507/bush

Chandler, D. (2002). Technological or media determinism. Retrieved from http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/tecdet/tecdet.html

Engelbart, D. (1962) Augmenting human intellect: A conceptual framework. Menlo Park: Stanford Research Institute.

Heidegger, M. (1993). Basic writings. (D.F. Krell, Ed.). San Francisco: Harper Collins.

—–. (1962). Being and time. (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). San Francisco: Harper Collins.

Keen, A. (2007). The cult of the amateur: How today’s internet is killing our culture. New York: Doubleday.

Lasch, C. (1979). The culture of narcissism: American life in an age of diminishing expectations. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

McLuhan, M. (1962). The Gutenberg galaxy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Postman, N. (1993). Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. New York: Vintage.

Surowiecki, J. (2005). The wisdom of crowds. Toronto: Anchor.

Turner, F. (2006). From counterculture to cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the rise of digital utopianism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

—–. (2005). Where the counterculture met the new economy: The WELL and the origins of virtual community. Technology and Culture, 46(3), 485–512.

Wittgenstein, L. (1969). On certainty. New York: Harper.

November 29, 2009 No Comments

Commentary 3 – text will remain

Hi everyone,

Hayles explains that sometime between 1995 and 1997 a shift in Web literature occurred: before 1995 hypertexts were primarily text based with “with navigation systems mostly confined to moving from one block of text to another (Hayles, 2003).” Post 1997, Hayles states that “electronic literature devises artistic strategies to create effects specific to electronic environments (2003).”

Bolter and Kress both contend that technology and text have fused into a single entity. That is, in the latter half of the 20th century, the visual representation of text has been transformed to include visual representations of pictures, graphics, and illustrations. Bolter states that “the late age of print is visual rather than linguistic . . . print and prose are undertaking to remediate static and moving images as they appear in photography, film, television and the computer (Bolter, 2001, p. 48)” Cyber magazines such as Mondo 2000 and WIRED are “aggressively remediating the visual style of television and digital media” with a “hectic, hypermediated style (Bolter, 2001, p. 51).” Kress notes that “the distinct cultural technologies for representation and for dissemination have become conflated—and not only in popular commonsense, so that the decline of the book has been seen as the decline of writing and vice versa (Kress, p.6).” In recent years, perhaps due to increased bandwidth, the WWW has had a much greater presence of multimedia such as pictures, video, games, and animations. As a result, there is a noticeably less text than what appeared in the first web pages designed for Mosaic in 1993. Furthermore, the WWW is increasingly being inundated with advertisements.

Additionally, text and use of imagery is also evident in magazines that also use visual representations of pictures, graphics, and illustrations as visual aids to their texts. Tabloid magazines such as Cosmo, People, and FHM are filled with advertisements. For example, the April 2008 edition of Vogue has a total of 378 pages. Sixty-seven of these pages are dedicated to text, while 378 pages are full-page advertisements.

While there are increasingly more spaces, both in cyberspace and printed works, that contain much imagery and text, there still exist spaces that are, for the most part, text-based. This is especially evident in academia. For example, academic journals, whether online or printed, are still primarily text. Pictures, graphics, and illustrations are used almost exclusively to illustrate a concept and, to my knowledge, have not yet included video. University texts and course-companions are primarily text as well. Perhaps, as Bolter states, this is because “we still regard printed books and journals as the place to locate our most prestigious texts (Bolter, forthcoming).” However, if literature and humanistic scholarship continues to be printed, it could be further marginalized within our culture (ibid).

Despite there being a “breakout of the visual” in both print and electronic media, Bolter makes a very strong argument that, text can never being eliminated in the electronic form that it currently exists. That is, all videos, images, animations, and virtual reality all exist on an underlying base of computer code. What might happen instead is the “devaluation of writing in comparison with perceptual presentation (Bolter, forthcoming).” The World Wide Web is an example of this. The WWW provides a space in which millions of authors can write their own opinions; Bolter is, in fact, doing this for his forthcoming publication “Degrees of Freedom”. The difference between Bolter’s text and others is that he uses minimal use of imagery and relies almost entirely on his prose to convey they meaning of his writing. Be that as it may, Bolter contends that the majority of WWW authors use videos and graphics to illustrate their words (forthcoming). Text will remain a large part of how we learn absorb and communicate information, however, “the verbal text must now struggle to assert its legitimacy in a space increasingly dominated by visual modes of representation (Bolter, forthcoming).”

John

References

Bolter, Jay David. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print [2nd edition]. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Bolter, Jay David. (forthcoming). Degrees of Freedom. Retrieved November 28, 2009 from http://www.uv.es/~fores/programa/bolter_freedom.html.

Hayles, Katherine. (2003). Deeper into the Machine: The Future of Electronic Literature. Culture Machine. 5. Retrieved, August 2, 2009, from http://www.culturemachine.net/index.php/cm/article/viewArticle/245/241

Kress, G. (2005). Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge, and learning Gunther Kress. Computers and Composition, 22(1), 5–22.

November 29, 2009 1 Comment

Commentary 3: Web 2.0 in Education

One of the most interesting and telling statements in the article, ‘Web 2.0 A New Wave of Innovation for Teaching and Learning?’ comes when author Bryan Alexander is discussing the wiki. After describing how the wiki works he says, “They originally hit the Web in the late 1990s (another sign that Web 2.0 is emergent and historical)”. (Alexander, 2006) To refer to something from the late 1990s as ‘historical’ shows how rapidly web 2.0 is developing and changing. But this rapid development, the thing that makes web 2.0 so interesting and exciting may also be the biggest problem this emergent technology faces. Anderson’s article is specifically intended to discuss the use of Web 2.0 in education, yet Web 2.0 has developed so fast that it has gone beyond the comfort level of many educators. Even teachers who are at ease with the technology are leery of much Web 2.0 content, believing that the openness of Web 2.0, one of its key features, makes it rife with faulty information. Much about Web 2.0 can be discussed and described, with the caveat, ‘on the one hand…but on the other hand…’ Even Anderson, whose intent is to showcase the positive aspects of Web 2.0 appears somewhat cautious of making a categorically positive statement and has included a question mark in his title, inviting the reader to decide on the verisimilitude of the title statement. This commentary will look at the Anderson article from the point of view of an educator with limited experience and knowledge of Web 2.0 and point out where some of the problems lie that will prevent this technology from gaining complete acceptance in an education setting.

As any new technology does, Web 2.0 has developed a user language; phrases, terms and even acronyms that are understood by developers and frequent users but can be problematic for the uninitiated. The article was originally published by Educause, which bills itself as, ‘a non-profit association whose mission is to advance higher education by promoting the intelligent use of Information Technology’. With this mission statement one can assume that the article was intended for educators, not Information Technology specialists. Yet within the article, Alexander writes in a way that many educators may find confusing. Anderson points out that even the term ‘social bookmarking’ could be confusing to some users yet then goes on in the article to use such phrases as, “Ajax- style pages”, (Alexander, 2006) or, “Web 2.0 can break on silos but thrive in shared services”. (Alexander, 2006) One of the most effective ways of separating something from acceptance by the general public is to use a specialized language.

Since the article is about the educational use of Web 2.0 Anderson discusses how the open structure of social bookmarking sites can be used with respect to research. He envisions the collaborative sharing of research between students and instructors and gives examples of how this could be achieved using Web 2.0 based sites where the open structure allows people to not only read but to change and contribute to a site. As intriguing as this is there are two problems with this notion, both of them related to the open structure of Web 2.0. The problems are the quality of the information that is being shared and the quantity of information available. Of the two, quality is by far the most serious for the student. In the article Alexander talks about one of the best known user controlled sites, Wikipedia, an open structured site which “allows users to edit each encyclopaedia entry”. (Alexander, 2006) Unfortunately the very openness of a site like Wikipedia and others like it can make the site unreliable. Wikipedia and other open sites allow anyone to add or say anything they want. Its hoped that the nature of these sites, which allows readers not only to contribute but to edit material, will naturally weed out information that is suspect or even wrong, but this is not always the case and many teachers now specifically advise students not to use material that has been found on Wikipedia.

Blogs are another aspect of Web 2.0 that Anderson discusses in terms of their pedagogical possibilities. He describes how, “Students can search the blogosphere for political commentary, current cultural items, public development s in science, business news, and so on.” (Alexander, 2006) While this is true and blogs can allow students and researchers to find and share the most current material in their field, the popularity of blogs has made this a challenge. A recent Google Blog search with the terms, ‘Digital Literacy’ returned over 350,000 hits, and one with the very general term, ‘Web 2.0’ returned over 49 million, which leaves one wondering, is this really useful? How many of these will a researcher actually look at and how much time must be invested to do so. Realizing this problem Anderson then goes on to discuss services that can be used to filter search results, which rather than simplifying the process only made the process seem, at least for this reader, even more complicated.

If Web 2.0 is to become ‘a new wave of innovation for teaching and learning’ its first hurdle will be educators. The problems outlined above will have to be considered and there may have to be a change in direction in how Web 2.0 is presented. Web 2.0 is relatively new, despite Anderson’s ‘historical’ comment and needs an introduction. Educators don’t want to be overwhelmed by the possibilities or fantasies about what could be, or have to deal with a steep learning curve, they want to understand the basic concepts and to know how they can start using it now. The article would have served educators better if Anderson had shown how a Wiki or a blog could be used on a small scale, e.g., show how a Wiki could be used by a group of students to collect material for a project. Once educators had some experience and improved their comfort level they could move beyond the classroom and use the technology to its fullest potential.

Alexander, B. (2006). Web 2.0 A New Wave of Innovation for Teaching and Learning? Educause , 33-44.

November 28, 2009 1 Comment

Final Project – Graphic Novels, Improving Literacy

Before I started this course, I had noticed the increased availability of graphic novels in our school library. My teenage son is a fan, preferring Manga to the North American style comic books. When our school recently began school-wide silent reading to promote literacy, student interest in and requests for graphic novels increased further. There seemed a clear link between this form of literature and the need to improve literacy rates as part of our province’s Student Success initiatives.

In the past weeks, I researched the topic of graphic novels to find the link between improved literacy and an alternate form of literature. This website is meant to be an informative document. My hope is to link it to the school website for parents to find documented answers to their questions about how to get reluctant readers engaged in regular reading.

A website is unlike a traditional essay in that I found it difficult to conclude the document. You will find both internal and external links. Typical of websites, the readers can choose the path to follow – it was never meant to be linear. Ultimately, I hope this site encourages readers to continue their own journey in learning about graphic novels.

November 28, 2009 1 Comment

Commentary 3

For this last commentary, I have selected Bolter’s chapter 9: Writing the Self. I felt this was appropriate as this course has initiated and altered my own thoughts on writing and the affects that writing technology has on the way we think and the way we interact with the actual technology.

Bolter begins the chapter with the following statement:

Writing technologies, in particular electronic writing today, do not determine how we think or how we define ourselves. Rather, they participate in our cultural redefinitions of self, knowledge and experience. (Bolter, 2001, pg.189)

As a society, we are influenced by the technologies that exist and aid in our existence. The early hunters and gathers were aided and influenced by the use of stone and stick- to which they fashioned tools to hunt and to aid in the preservation of foods. As a society in the knowledge age, we are influenced by our use of technologies that aid us in the rapid creation and transfer of knowledge. We exist through the instantaneous movement of 1s and 0s, which has transformed the very quality of our life. To imagine an existence without these technologies would be a kin to imagining what life would be like to live in a third world without food and shelter. This existence is prevalent across the world, but not an existence that many Canadians (excluding new Canadians) can identify with.

Bolter continues in his chapter by claiming “for many, electronic writing is coming to be regarded as a more authentic or appropriate space for the inscription of the self than print.” (pg. 190) I ask, is this because we truly know no other space? Just as I can not identify with the conditions of may inhabitants of this planet, I also can not identify with those ancient cultures who used ancient technologies to carve hieroglyphs and symbols onto tablets; or cultures who employed papyrus to convey the thoughts of the time. This same logic can be compared to the many seniors who can not grasp and use the computer and internet today; technologies that were not influencing factors in this existence!

Bolter furthers is chapter by stating that “writing is seen to foster analysis and reflection” (pg. 192) and “writing becomes a tool for reorganizing, for classifying, for developing and maintaining categories.” (pg. 193) Considering the vast amount of knowledge and information that is available, this statement is logical. Perhaps the question that one should ask is which came first, the changes in the use of writing as a knowledge organizer or the amount of knowledge that was available which required to be organized? Generally speaking, members of a society create or modify tools for a need and not as an accident. While much like the preverbal genesis of the chicken and egg, the answer would provide the foundations for the affects of writing technologies.

Lastly, the portion of the chapter that I was most intrigued with implicated current writing technologies and a refined experience for the author As “the technology of writing has always had a reflexive quality, allowing writers to see themselves in what they write” (Bolter, pg. 189), the desire of a writer want to “change her identity, by assuming a different name and providing a different description” (Bolter, pg. 199) allows the opportunity to create false selves in many virtual worlds including Second Life and chat rooms. While writing can be a wonderful venue to escape the world, the creation of false worlds can lead to serious repercussions if the author can separate the real from the fiction.

References

Bolter, J. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Mahwah, N.J. USA.

November 28, 2009 1 Comment

Web 2.0

Introduction

Bryan Alexander’s article “Web 2.0: A new wave of innovation for teaching and learning” relays the emergence and importance of Web 2.0 in information discovery. It highlights a number of important aspects of Web 2.0 including social networking, microcontent, openness, and folksonomy, and than continues on to describe how it can enhance pedagogical ideologies. Each of these characteristics will be examined below.

Information on the Internet is presented in a variety of ways. Graphics and multi-media now define the Web, challenging the very definition of literacy. Information flows in numerous directions and paths offering the ‘reader’ or ‘visitor’ multi-layered information. Web 2.0 is based on interactions between people in asynchronous and synchronous communication, offering flexability and accomodation. This has a significant impact on our society, education system and our culture.

Definition

There is much debate over the definition of Web 2.0. Alexander (2008) defines Web 2.0 as “…a way of creating Web pages focusing on microcontent and social connections between people” (Alexander, 2008, p. 151). Wikepedia defines Web 2.0 as “…commonly associated with web applications which facilitate interactive information sharing, interoperability, user-centered design and collaboration on the World Wide Web” (Wikepedia, 2009). Many argue that this is not something that is a recent technological invention, but more of an evolution of sorts.

Social Networks

Social networking is one of the major characteristics of Web 2.0. This includes listservs, Usenet groups, discussion software, groupware, Web-based communities, blogs, wikis, podcasts, and videoblogs, which includes MySpace, Facebook and Youtube (Alexander, 2008). Facebook alone has thousands of users, allowing people to stay connected using a variety of methods.

“Social bookmarking is a method for Internet users to share, organize, search, and manage bookmarks of web resources” (Wikepedia, 2009). Social bookmarking and networking are constantly evolving, changing and metamorphing ways to acquire knowledge and stay connected. It allows various people from around the world to bond together and engage, where otherwise this would not be possible. It enlarges the definition of community and links people by topic, concerns, human interest, educational needs, political perspectives, etc. For example, Twitter allows people to instantly communicate with their ‘followers’. This type of social networking was used recently during the American Presidential campaign to keep voters and constituants in touch. Instant messaging allows spontaneous contact with others, which is strongly associated with the characteristics of immediacy within our society.

Microcontent

One critical aspect of social networking is microcontent. Microcontent is an important building block of the Web as information is in bite size pieces that can be accumulated, edited, manipulated and saved. Microcontent allows participants to contribute small pieces of information that can take little time and energy, is easy to use, and provides foundational pieces to web pages. An example of this is Blogs and Wikis.

Openness

Another characteristic that Blogs and Wikis share is openness and accessibility. Openness is “…a hallmark of this emergent movement, both ideologically and technologically” (Alexander, 2006, p. 34). Users are considered the foundation in this information architecture (Alexander, 2006), and therefore play a pivotal role in developing, creating and designing spaces. Participation is key and Web 2.0 encourages openness and participation from all.

Folksonomy

“A folksonomy is a system of classification derived from the practice and method of collaboratively creating and managing tags to annotate and categorize content” (Wikepedia, 2009). Managing tags and collecting information from peers is an important aspect of social networking and Web 2.0. Tags and hyperlinks are two of the most important inventions of the last 50 years (Kelly, 2006). By linking pages each book can refer to multiple other books. References and text are endlessly linked to each other, creating exponential knowledge.

Pedagogical Implications

There are many pedagogical implications that come with the advent of Web 2.0. A list of beneficial websites, ideas and tools for teaching with Web 2.0 applications were put together by myself, using Webslides, and can be found at http://www.diigo.com/list/etec540debg/head-of-the-class-with-web-20. These tools can be a valuable asset in the classroom.

Social bookmarking can play a role in “collaborative information discovery” (Alexander, 2006, p. 36) allowing students to connect with others, follow links and research references. It can also enhance student group learning, build on collaborative knowledge and assist in peer editing (Alexander, 2006).

“The rich search possibilities opened up by these tools can further enhance the pedagogy of current events” (Alexander, 2006, p. 40). This allows students to follow a search over weeks, semester or a year (Alexander, 2006). The ability to analyze how information, a story or an idea changes over time allows collaboration between classes and departments and provides the ability to track progress (Alexander, 2006).

Wikis and Blogs can chronicle student’s development over a semester, provide occasions for partnering and discussion, and provide opportunities to practice literacy skills and communication techniques. Blogs and Wikis can give each student a voice and provide equal opportunities for all participants. Storytelling provides creativity and allows students the opportunity to tell their own story. Chat can develop critical thinking skills while podcasting and voicethread can develop opportunities for documentation and interaction.

The interactivity that Web 2.0 offers encourages group productivity and consultation. Projects like connecting students with real-time astronauts or with sister schools in another country heightens learner interest. Whether it is Science fairs or projects, English literature, history or social studies, Web 2.0 can enhance the multiple aspects of the learning paradigm.

Alexander’s arguments are compelling, however, he does not address the downside of Web 2.0. This would include cyberbullying, cyber-predators, web cameras used for pornography, and the unreliability of the Internet. Accessibility and openness is all inclusive, meaning right and wrong information can be contributed. Learners need to be taught how to find reliable sources on the Web while sifting through mountains of information with a critical eye. The Internet is a Pandora box of sorts – the good comes with the evil. Not every technology and Web innervation has acceptable pedagogical implications, or can be used appropriately in the classroom. Applications can be unstable, come with technical issues, and can be cost prohibitive for those that come with licenses. Applications are tools to be used to assist in learning and not to replace exceptional teaching methods. However, even with multiple tools available, teachers may not use them as they may not be available for every class, they do not have the knowledge to use them, or find them too time consuming.

The Future

The future of Web 2.0 is Web 3.0, which will be a highly interactive and user-friendly version. The advancement of the above characteristics will ideally enhance applications that are already being used, and provide new applications/opportunities for learning. Skills that are developed in the classroom now will prepare students with the necessary skills that they will require in their future workplaces.

Conclusion

The evolution of the Web will continue to ebb and flow and evolve over time, bringing learners and creators together (Alexander, 2006). Gone are the days of ‘reading’ web pages, which are now designed to be more interactive and purposeful, inundating the user with myriads of information. The availability of social networking, microcontent, folksonomy and openness on the Web will continue to provide learners and educators with multiple learning opportunities. With guidance from the educator, learners can be provided with positive learning outcomes, while using multi-layered applications.

References

Alexander, B. (2006). Web 2.0: A new wave of innovation for teaching and learning? Educause Review, 41(2), 34-44. Retrieved April 5, 2008, from http://www.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ERM0621.pdf

Alexander, B. (2008).Web 2.0 and Emergent Multiliteracies. Theory into practice.47(2), 150-60. Retrieved July 20, 2009, from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00405840801992371

Kelly, K. (May 2006). Scan this Book. The New York Times.

Wikepedia. (2009). Folksonomy. Retrieved November 11, 2009 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Folksonomy

Wikepedia. (2009). Social bookmarking. Retrieved November 11, 2009 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_bookmarking

Wikipedia. (2009). Web 2.0. Retrieved November 11, 2009 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_2.0

November 28, 2009 1 Comment

from mash up to mad

SoI had this great idea of mashing up the same song by two different artists, Tom Waits doing his song ‘Long Way Home’ and Norah Jones doing her version of the same song. I worked at it for quite a while, then thought, o.k. that’s long enough I’ll post what I’ve got. Unfortunately, after all that time the security wouldn’t allow it. Gee was I happy. So instead I’m going to follow John’s lead and post something that I did last summer for another class. I like it better than the resulting song that i got anyway, it was a bit rough and the transitions weren’t quite as smooth as i would have liked. You can find the PhotoPeach story here . (Make sure your speakers are on)

November 28, 2009 1 Comment

The rising influence of the visual over the purely written word.

The rising influence of the visual over the purely written word.

Third Formal Commentary

Richard Biel

University of British Columbia

Etec 540

Professors Jeff Miller and Brian Lamb

Many have claimed the death of the author is nigh (Barthes, 1968). One of Michel Foucault’s most pivotal works “What is an author?” may have even started the dirge. Kress (2005) and Bolter (2001) do not go as far as that but they do both argue that there is an incredible change that is presently occurring. Information and knowledge are moving from the long standing dominance of writing to a multi-modal form of communication best exemplified by the Internet and the webpage however extending far past this to more common forms of text. This “remediation” as Bolter (2001) phrases it, is causing a shift in power from the author to the reader. The reason for this shift is the limitations of text and the development of technology that allows this change to occur. Both authors are wary of being labelled technological determinists and distance themselves from this position citing the complexity of human/societal/technological relationships. One thing is for certain whether the advent of the Internet and hypertext is the executor of the author is questionable however they most certainly have mutagenic capabilities.

In the natural sciences there are a number of species that have, despite all odds, hung on for a “unnaturally” long period of time. Kress (2005) contends that this is certainly the case for writing. Writing has had and continues to have a very prominent place in the dissemination of information, knowledge and entertainment. However this dominant role of writing is changing. “In particular, it seems evident to many commentators that writing is giving way, is being displaced by image in many instances of communication where previously it had held sway.” (Kress, 2005). Bolter (2001) contends that text and writing actually, “contained and constrained the images on the printed page.” The rise of the image in dominance is demonstrated on an almost daily basis by newspapers, textbooks and magazines that are resembling more and more like webpages and hypertext. I doubt very much that writing not supported by other multi-modal forms of communication will be completely supplanted however there is no doubt that a change is occurring towards a more visually dominant age.

Traditionally the author of the written word has taken a far more prominent role when it came to the author/reader power differential. This relationship is changing. The author traditionally had control over syntax, grammar, word order, word choice and a myriad of other conventions that allowed the author to dictate how information and knowledge was metered out. Readers traditionally took more passive roles in their interaction with the written word but with the ever growing prominence of the visual image “ we get a reverse ekphrasis in which images are given the task of explaining words.” (Bolter, 2001). This is best exemplified by the “novelization” of films. Where films are first released and then the novel is written almost as a second thought. “In a multimodal text, writing may be central, or it may not; on screens writing may not feature in mulimodal texts that use sound-effect and the soundtrack of a musical score, use speech, moving and still images of various kinds.” (Kress, 2005). Both Kress (2005) and Bolter (2001) recognize that we are currently living in the age of the visual and the written word, although still highly regarded, is slowly taking a backseat to the visual.

So why has the written word been bumped out of the drivers seat? This can best be explained by outlining the limitations of the written word. Kress (2005) contends that individual words are vague and rely to heavily upon the interpretation of the reader. An image, on the other hand, is far less open to interpretation by the viewer. However, I would argue that images can be manipulated to highlight different aspects of the images and downplay others and thus lead viewers to interpret the images in particular ways. Images, Kress(2005) contends have a much greater capacity and diversity of meaning. “Hypermedia can be regarded as a kind of picture writing, which refashions the qualities of both traditional picture writing and phonetic writing.” (Botler, 2001). Although a purely written text is being relegated to the halls of academia and higher thought it still has a place in supporting the successful transmission of information and knowledge.

Multi-modal representations have become common place in the visually rich culture of the western world. Traditional forms of concept transmission such as the written word are being re-tooled and enhanced with sound, video and images. Kress (2005) and Bolter (2001) both contend that this is to the betterment of the media as a far richer and more diverse form of communication is evolving. The purely written word that is supported with few if any images is being pushed to the margins of higher learning and thought. With the advent of digital media we will continue to be offered a greater diversity and more individualistic experience when it comes to information, knowledge and communication.

References

Barthes, Roland (1968). The death of the author. Downloaded on November 28th, 2009. From http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=DuEOAAAAQAAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA101&dq=Death+of+the+author&ots=XaTIKFKF-_&sig=3OZbsPgu2tt2X2oTR4euZW2GB3o#v=onepage&q=Death%20of%20the%20author&f=false

Bolter, Jay D. (2001). Writing Spaces: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, Mahwah, New Jersey, London.

Foucault, Michel (1977). What is an author? In Language, counter-memory, practice: Selected essays and interviews (pp.113-138). (D. F. Bouchard & S. Simon, Trans. ). Ithaca, N.Y.:Cornell University

Kress, Gunther (2005). Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge, and learning. Computers and Compostion 22, pp.5-22.

November 28, 2009 No Comments

Social Technologies List

In response to the Rip.Mix.Feed activity I created a Wiki in which we can list sites we have used in creating our projects, collaboratively creating a list of resources all in one place that we could access when we need. I have started us off with 25 sites and would love to have others add new sites and catagories from their own experiences!

The Wiki is called called Social Technologies List and can be accessed with the following information:

- username: metubc

- password: ubcmet

You can also log in through http://socialtechnologieslist.wiki-site.com/ . It would be so incredible to have an ongoing site we could all add to and pull from when needed! We can keep it up after the course ends and add to/pull from the site as needed.

~~Caroline~~

November 27, 2009 No Comments

Une Autre Vie

For my project I decided to create a slideshow which allowed me to create a sort of montage of abstract feelings, experiences and thoughts about living in Paris for two years.

In commencing the project I had an idea already in my head of what I wanted but the challenge was to locate programs which would do what I needed them to do and provide the dark, artsy effects I was looking for. Many of the sites allow for playful photo editing and slideshow production but I managed to locate one that allowed for a bit more.

I originally created the show through slide.com but found the program limiting despite its user-friendly approach. I realized it was not really me who was in control of the creation. I looked at mytimeline.com and while it provided what I was looking for in terms of effects, the background was unchangeable and did not give the right feel to it. I was searching for a site that would allow transitions, 15+ slides, text additions on the slides themselves, music, and…was free. I was asking for a lot!

Through Kizoa I found a program that did everything I wanted, with a few catches, however. The transition selection is great, slide number is perfect, but you need to pay a fee to either add text or your own music. In my stubborn quest to find free resources, I continued to search and could not locate a single site which would serve my needs and provide the right feel. After doing some creative work with Picnik, a free photo edit site which you can access online without downloading, I added text to the images. Within Kizoa, I located a song that would work and put it all together.