“I’ll put a girdle round about the earth in forty minutes.” (Midsummer Night’s Dream, ii. 2.)

The dream of traversing the globe, thereby compressing space and time was a concept that fascinated the imaginations of the Renaissance and was captured by Shakespeare’s character Puck in Midsummer Night’s Dream. Electricity, as discovered through the work of Franklin, Newton and others brought this reality closer, but it wasn’t until the early 19th century that the possibility of a global communication network became more possible. In Europe, the invention of the telegraph by Wheatstone and Cooke, and simultaneously, Morse in America brought about an information transmission revolution that would break down time and space, provide a new layer to literacy and communication, extend the spaces of writing and shrink the Victorian world into a more manageable global network.

The dream of traversing the globe, thereby compressing space and time was a concept that fascinated the imaginations of the Renaissance and was captured by Shakespeare’s character Puck in Midsummer Night’s Dream. Electricity, as discovered through the work of Franklin, Newton and others brought this reality closer, but it wasn’t until the early 19th century that the possibility of a global communication network became more possible. In Europe, the invention of the telegraph by Wheatstone and Cooke, and simultaneously, Morse in America brought about an information transmission revolution that would break down time and space, provide a new layer to literacy and communication, extend the spaces of writing and shrink the Victorian world into a more manageable global network.

Since traditional communication was hampered by distance, conquering that distance was the key to increase the speed of communications. The telegraph was designed to send information as alterations in electrical signals and its inventors Cooke and Wheatstone in Europe and Morse in America produced the first working telegraph in 1836. (Willmore 2002) The social impact of this technology and new space of text brought a sense of immediacy to Victorian society. According to Morus (2002), the telegraph made their world smaller and more manageable, as well as increasing their faith in progress and the power of science. The human mind coupled with the power of science was able to take the power of lightning, harness it and utilize it to enable instantaneous communication.

Since traditional communication was hampered by distance, conquering that distance was the key to increase the speed of communications. The telegraph was designed to send information as alterations in electrical signals and its inventors Cooke and Wheatstone in Europe and Morse in America produced the first working telegraph in 1836. (Willmore 2002) The social impact of this technology and new space of text brought a sense of immediacy to Victorian society. According to Morus (2002), the telegraph made their world smaller and more manageable, as well as increasing their faith in progress and the power of science. The human mind coupled with the power of science was able to take the power of lightning, harness it and utilize it to enable instantaneous communication.

Space and Time Compression

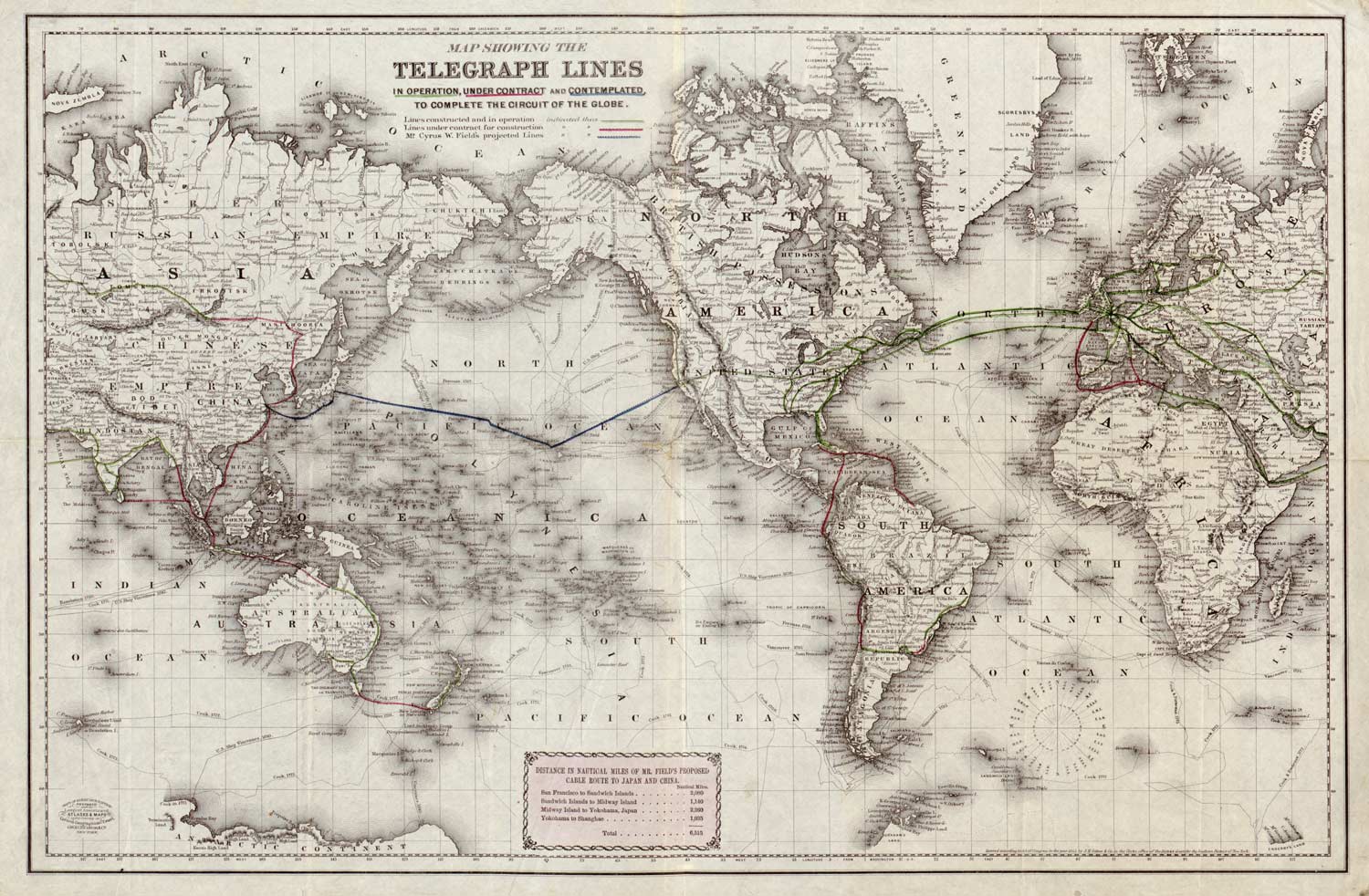

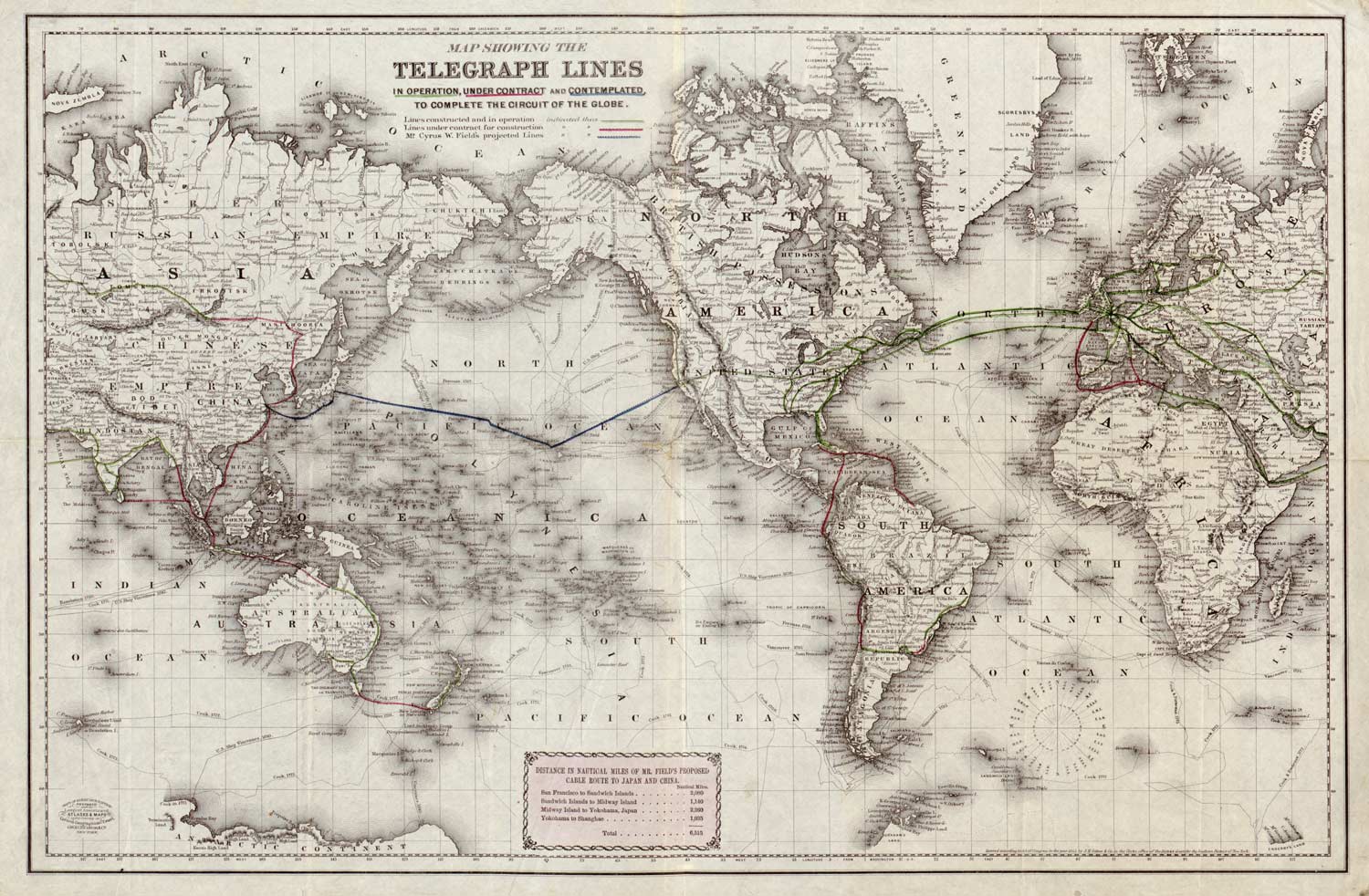

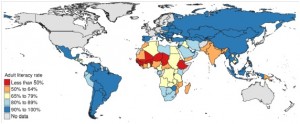

The impact of the invention is evident in its rapid expansion across the globe. By 1866 North America and Europe were connected, followed by India in 1870, Japan, China and Australia in 1871, the Caribbean in 1872, followed by South America in 1874 and across Africa between 1879 -1886. (MacMahon, 2002) The Imperial forces behind this expansion reveal a global strategic reach to impact international trade and an extended military reach, with British and American engineers driving deeply into their spheres of influences and colonies and connecting them. MacMahon (2002) writes that by 1895, there was over 300 000 km of undersea cables, and over 1 million km of lines of cable across the land masses, sending approximately 15000 messages daily, of which the British controlled 70% of the global capacity. So influential was this new form of communication that the telegraph became the first industrial monopoly in the United States in the form of the Western Union Telegraph Company. (du Boff, 1984) Its impact on society was enormous, since journalists, businessmen and railway engineers began to utilize it on a large scale for the spread of information about everything from news, to market prices to the position of trains. Yet its ability to compress time and space and create a global community, along with its impact on text spaces across the literate world was perhaps the most important result of the invention of the telegraph.

With a potential to unite humanity across space and time, the telegraph had the potential to distribute knowledge evenly and instantly across the earth. Instantaneous communication became a possibility as telegraphic webs spread across all regions of the world, and people could know what was happening in distant cities at a particular moment (Otis, 2002) . The telegraph altered the sense of time and space and distance became less meaningful as people were able to communicate instantaneously. Even Morse, the American inventor of the telegraph, boasted in 1883 that “space [is] annihilated.”(Otis, 2002, p.121) Electricity, a mysterious force of nature, was now subservient to human intelligence, and like a global nervous system, it enabled the spread of information from a central point across the world. The very notion of time and space must have been completely transformed. Richard du Boff (1984), in his studies of the telegraph, relates how a journalist in 1867 found the telegraph system to be invaluable, since it would “…bring all civilized nations into instantaneous communication with each other.” (du Boff, p.571) And at the base of this communication was the notion of standardized time.

Beginning in Britain, Greenwich time was transmitted directly to the centres of government, and soon Greenwich became the centre of all time in the British Empire’s network of clocks (Morus, 2000) . Thus a universal grid was set up based on Greenwich standard time, and the telegraph became a prerequisite for not only scheduling trains, communications and intelligence across the empire but perhaps also a prerequisite for everyday life. This technology brought about a change to the very essence of communication and existence through the concept of unmatched speed of communication. The importance of speed then, more than ever before, came to the forefront of technological development in communication, a theoretical framework that is still influential today, as seen in the work of Virilio (Bartram, 2004) . Telegraphy severed the bond between transportation and communication, since news no longer had to travel by boat or carriage, and was able to converge time and space bringing countries and continents together profoundly impacting economies, government, the military, intelligence, news and the spaces of writing. Text now existed in immediacy, which thereby impacted the perspective of self in time and space, as well as its power and influence.

In the essence of immediacy there is a remediation of community, a compression of space and time and a transformed sense of self in the world. The telegraph went far beyond the boundaries of orality, as outlined by Walter Ong (2002). In chapter 3 of his seminal work Orality and Literacy (2002), Ong outlines the characteristics of an oral culture. The impact of the telegraph on these characteristics is profound, since it took communication and expression to a completely new level, subordinating expression, making information more analytical, less redundant, more abstract as well as globally situational. The message was no longer participatory and empathetic, but delivered from every corner of the earth from a central location, similar in the way the brain delivers a message across the nervous system. With instantaneous communication through the telegraph, the progressive internalization and privatization of text now reached a new level in the 19th Century. (Ong, 2002) The body of the British Empire, with its cables, like a nervous system, spread across the world sending information in electrical signals, and this concept became a popular metaphor in Victorian England. (Morus, 2000) The Victorians’ perception of their own bodies thus became more abstract in that they not only changed the ways in which they perceive communication, but also their own minds and physical presence in the world. Marshall Machluan wrote that “visual man creates an environment that is strongly fragmented, individualistic, explicit, logical, specialized and detached”(MacDougall, 2011). With the advent of instantaneous global communication, this abstracted view of the world and an individual’s role within it came to the fore and enabled a new writing space – one that was global, outside of oneself and interconnected with all parts of the world. Ong (2002) writes that technology, if properly internalized, should enhance life since it can “enrich the human psyche, enlarge the human spirit and intensify its interior life.”(Ong, 2002, p.82) The telegraph certainly enriched the view of the world and must have caused an intensification of internal awareness of self within a global culture. Yet what went even farther was the concept of a universal language of telegraphy invented by Morse.

A New System of Symbols

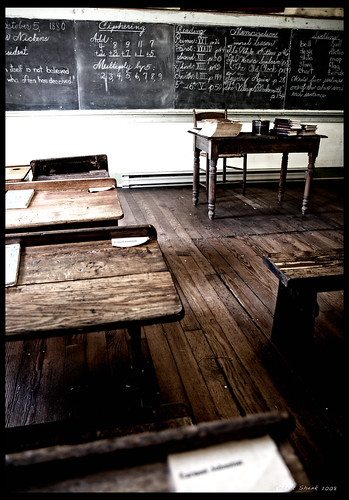

Bolter (2001) writes that each technology of writing involves different materials and different employment of methods of utilization of those materials, all of which are significant. The Morse code enabled a new system of signs to represent human language that could easily be transmitted across the wires of the global telegraph system and could be understood across the languages, but was still based upon the English alphabet. The Morse code, a feat of human ingenuity, required transcribing natural language into another symbol system that was representative of the English alphabet (Lucky, 2000). This is a remediation of text on a completely new level, since it represented the alphabet, which was already a representation of natural language, in a form that was readable by a machine. The abstract nature of compressing language into a compact form that could be transmitted by electrical signals provided even greater speeds of communication. Once learned, the Morse code could be deciphered by the sound of its transmission and the sight of its dots and dashes, thereby incorporating the oral aspects of ear and eye into the communication. The telegraph required operators to be able to decode and translate the English alphabet, which was a cultural skill built around the context of literacy, immediacy and a global community. Ong (2002) points out that print provided a sense of closure with its fixed point of view and fixed tone, which showed the distance between the writer and reader. The telegraph enabled a secondary orality (Ong, 2002) which provided a global audience for a message originating electronically from one point to move to another in an instantaneous transmission across the spaces of the earth. This technology of instant communication transformed geography from regional or national to a truly global network.

Bolter (2001) writes that each technology of writing involves different materials and different employment of methods of utilization of those materials, all of which are significant. The Morse code enabled a new system of signs to represent human language that could easily be transmitted across the wires of the global telegraph system and could be understood across the languages, but was still based upon the English alphabet. The Morse code, a feat of human ingenuity, required transcribing natural language into another symbol system that was representative of the English alphabet (Lucky, 2000). This is a remediation of text on a completely new level, since it represented the alphabet, which was already a representation of natural language, in a form that was readable by a machine. The abstract nature of compressing language into a compact form that could be transmitted by electrical signals provided even greater speeds of communication. Once learned, the Morse code could be deciphered by the sound of its transmission and the sight of its dots and dashes, thereby incorporating the oral aspects of ear and eye into the communication. The telegraph required operators to be able to decode and translate the English alphabet, which was a cultural skill built around the context of literacy, immediacy and a global community. Ong (2002) points out that print provided a sense of closure with its fixed point of view and fixed tone, which showed the distance between the writer and reader. The telegraph enabled a secondary orality (Ong, 2002) which provided a global audience for a message originating electronically from one point to move to another in an instantaneous transmission across the spaces of the earth. This technology of instant communication transformed geography from regional or national to a truly global network.

The new globalism created through the telegraph networks is a remediation of print, with the print technology becoming the agent of change and creating cultural competition between technologies.(Bolter, 2001) The Imperial drive of the British Empire to connect its far flung colonies closely to its information centres was enhanced through the telegraph, which altered the means of production and exchange of information on a global scale (du Boff, 1984), and gave rise to a global media system. It also enabled the possibility for cultural imperialism, since the Morse code was based on the English alphabet, could be controlled by a government and could be used for spreading information directly and quickly from the centres of the Empire. Bolter writes that electronic writing is always involved in material culture and economics of a time and space, within the intimate technical and cultural relations of writing (2001) . The impact of the telegraph on the economy, spread of information, imperial connection and surveillance, news and time on the new global space of text is profound.

The invention of the telegraph transformed the Victorian world of the 19th Century. Communication transformed from its direct links to the transportation of the time, such as ship or carriage, into a symbol-based code system based on electrical impulse. This transition to instantaneous information transfer based on the central time of Greenwich and transmitted on a global network of cabling created the first truly global community, and became the basis upon which we have built our modern internet. Electricity, which was seen as a mysterious force of nature as personified by Puck in Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, was harnessed by science and the human intellect to interconnect humanity. The perception of self in the world combined with a new technological anthropomorphism applied to global telegraphic cabling expanded the spaces of writing and reality.

With the Morse code, remediation of print was applied to a new level of secondary orality, in that a new symbol system was created to be applied on a global scale, based on the English alphabet. This symbol system required a new level of training for telegraph operators and those in the military or government services, so that they would be able to read, hear and translate Morse code back into English or their own language. The technology of text reached a new nexus with the telegraph, in that human language was applied to a machine through a new symbol system, and instantaneous communication was achieved. Telegraph stations became centres for hypertext connections, which enabled the boundaries to text, time and space to be eliminated and for a global, interconnected world to be realized. Corporate, government and Imperial forces combined to spread a “girdle” of cables around the entire earth, each spreading its own agenda, but impacting the societies of the world by providing instant communication in a short number of years. With the elimination of the barriers of time and space, as well as the need for communication to be based on traditional transportation methods, the telegraph provided a new world view, a transformation of the view of self and a textual space that spread far beyond the boundaries of the printed word into a new global communication system based on electricity. The invention of the telegraph not only transformed communication, it also set the foundations for a global networked society based on Informational Capitalism (Castells, 2004), wherein distance and time were becoming irrelevant and a global one-time system (Virilio, 1995) was beginning to be established, based on the Greenwich mean time. Writing and the space of printed text thus moved from print to a symbol system in an abstract space of signs (Bolter, 2001), transforming perspective, communication, sense of time and place as well as all aspects of society.

References

Bartram, Rob (2004). Visuality, Dromology and Time Compression : Paul Virilio’s New Ocularcentrism. Time Society 13: 285. DOI: 10.1177/0961463X04044577

Bolter, J. D. (2000). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print. Mahwah, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Castells, M. (2004). Informationalism, Networks, And The Network Society: A Theoretical Blueprint. In Castells, M. (Ed.), The Network Society: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

du Boff , Richard B.(1984) The Telegraph in Nineteenth-Century America: Technology and Monopoly. Comparative Studies in Society and History , Vol. 26, No. 4 (Oct., 1984), pp. 571-586 .

Kroker, Arthur and Marilouise (1995). Speed and Information: Cyberspace Alarm! Ctheory.net. Retrieved from http://www.ctheory.net/articles.aspx?id=72

Lucky, R. (2000). The Quickening of Science Communication. Science, 289(5477), 259. Retrieved from EBSCOhost.

MacDougall, R. C. (2011). Podcasting and Political Life. American Behavioral Scientist, 55(6), 714-732. doi:10.1177/0002764211406083

McMahon, P. (2002). Early Electrical Communications Technology and Structural Change in the International Political Economy—The Cases of Telegraphy and Radio. Prometheus, 20(4), 379-390. doi:10.1080/0810902021000023363

Morus, I. (2000). The nervous system of Britain : space, time and the electric telegraph in the Victorian age. British Journal for the History of Science, 33(4), 455-475. Retrieved from EBSCOhost.

Ong, W. J. (2002). Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. New York: Routledge.

Otis, L. (2002). The Metaphoric Circuit: Organic and Technological Communication in the Nineteenth Century. Journal of the History of Ideas, 63(1), 105.

Willmore, L. (2002). Government policies towards information and communication technologies: a historical perspective. Journal of Information Science, 28(2), 89.

Read this essay in Morse Code

based on web translation by: http://www.onlineconversion.com/morse_code.htm

Appendix A – Comparison of Telegraph and Internet Lines

Links to telegraph lines and internet lines

Appendix B – Videos for Further Viewing

Who Invented the Morse Code – from the History Channel

Transatlantic Cable

Comentary # 2: Hypertext as the Remediation of Print

In the Chapter “Writing as a Technology” Bolter argues that our technical relationship to the writing space takes place between readers and writers. Literacy is the realization that language can have both a visual and an aural dimension as the words emitted by some one can be recorded and shown to others who are not present at the time of recording (Bolter, 2002, p. 16). Technical and cultural dimensions of writing constitute text as a technology because it depends on the purposes of each culture and on the material properties of the techniques and devices that are used.

In the evolution of text today we are facing the change between print and electronic writing (hypertext). According to Bolter, hypertext is changing attitudes towards writing. The Web is changing so fast that it is difficult to predict its future impact (Smith & Ward, 2000). Other dimensions and other spaces are taking place within communication. These new forms constitute a challenge for Western identity and self-representation (Smith & Ward, 2000, p. 106). Within this transformation, we are experiencing remediation understood as a “process of cultural competition between or among technologies” (Bolter, 2002, p. 25).

Throughout history, innovations in text technologies have provoked the remediation of reading and writing. Currently we are facing the remediation of print, which includes the free interaction and combination of digital media and words. Over the 20th century print has entered in competition and combination of images, video and TV. Electronic text is more interactive and flexible than print, in words of Bolter, is hypertextual (Bolter, 2002, p. 26). According to Puntambekar (et. al., 2004) visual components of text, such as concept maps (which are intended to represent meaningful relationships between concepts) and networks, offer learning opportunities of reading and writing. These new technologies of text allow accentuating relevant characteristics of representation and making higher-order relations.

In the chapter “The Breakout of the Visual”, Bolter arugues that digital text has carried out revealing transformations in vocabulary and grammar. Hypertext has brought a redefinition of the way in which we communicate, specially regarding to organization and design of text. According to Bolter (2002), a webpage can be a scattering of alphabetic signs among visual components that addresses the writer and reader without references of speech. Graphical User Interface (GUI) constitutes such a text and integrates visual components to redefine both how text is organized and designed. The ways in which we present content, and the tools that we use for this purpose (.e.g. Prezi, Animoto, Glogster), also redefine both how text is organized and designed.

Bolter argues that printing has placed the word effectively in control of the image. Before print medieval society had developed a sophisticated iconography that served in the place of words for a largely illiterate audience. However, the literate population of Middle Ages was quite smaller than the current literate population. Today, hypertext has redefined the relationship between words and images. Image is a complementary element of text. The visual component has entered in our lives by the electronic writing space. In hypertext media designers and authors redefine the balance between word and image. The latter constitutes the remediation of print: a space in which images can break free of the constraint of words and tell their own stories (Bolter, 2000, p. 58).

In the article “Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge, and learning”, Gunther Kress (2005) argues that practices of writing and reading are transforming. New forms of representation leads us to more new forms of communication: “canonical forms of representation have come into question; the dominant modes of representation of speech and writing are being pushed to the margins of representation and replaced at the centre by the mode of image and by others” (Kress, 2005, p. 17). New practices of reading and writing are emerging from the engagement of text with image and/or depiction. Within this engagement the reader designs the meaning from materials made available on the screen, on the new kinds of pages.

Kress discuss about the possible gains and losses when moving from representation through writing to representation through image. According to Kress (2005) we are experiencing realignment in culturally valued modes. Writing is being displaced by image in many instances of communication where previously it had dominated. We are experiencing a revolution of the modes of representation and of the media of dissemination. There have been changes in the way in which pages were organized and how they were designed. With the electronic text, the new organizing principle of this new page is the shape of the life-worlds of potential visitors that find information (Kress, 2005). Speech and writing tell the world, as they are, above all, modes founded on words in order. Images show the world, as they are modes founded on depictions. Words rely on conventional acceptance and are always general and vague.

The three articles/chapters discussed in this comentary speak of an evolution of technology from print to digital text (hypertext). Both Bolter and Kress argue that transformation has brought new forms of representation, which has been expressed in an explosion of visual elements within text. Moreover, Bolter argues that it is a process of remediation of print, consisting of an interaction between text and visual components as complementary elements of the act of reading and writing. The new form of text that comes up from this interaction (hypertext) is an intensification of print as the reader become conscious of the form or medium itself and of his/her interaction with it (Bolter, p. 43). It provides a new strategy, which involves interactivity and the unification of text and graphics for achieving an authentic experience for the reader. It is a remediation of print, as it offers different uses for texts and takes different forms (e.g. eBooks, electronic encyclopedia, electronic journals, electronic libraries, etc.). Will hypertext lead to the disappearance of print? Bolter suggest that both print and hypertext need each other in a sense of competence. Print finds necessary to compete against digital technologies in order to maintain their readers. On the other hand, print is becoming “hypermediated”, although it still seems more natural and simple than digital text is.

References

Bolter, J.D. (2002). Writing Space. Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print. New York: Routledge.

Kress, G (2005). Gains and losses: New forms of texts, knowledge, and learning. Computers and Composition,22, 5-22. Retreived October 20, 2011 from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S8755461504000660

Puntambeka, S. Stylianou, A, & Hübscher, R (2004). Improving navigation and learning in hypertext environments with navigable concept maps. Human Computer. 18 (4), 325-372. Retrieved November 4, 2011 from http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1466543.1466546&preflayout=flat#prox