Many students who have been educated in North American classrooms during the latter half of the 20th century have experienced lessons taught by teachers using overhead projectors. I vividly recall such lessons taught in my elementary and high school classrooms, as the ubiquitous fluorescent light would suddenly disappear and be replaced by a single rectangular headlight illuminating a vacant white canvas at the front of the room. The teacher’s voice was then heard as her large shadowy hand entered the bright stage and began to fill it up with words, diagrams, symbols, formulas, etc. Most of the students would hurriedly get out their notebooks and begin to copy down, as quickly and as neatly as they could, whatever information appeared in this illuminated space. The overhead projector played a significant role in my educational history, both as a student and later on as an elementary teacher, offering a viable alternative to the traditional blackboard. It is a tool of educational technology that was developed not only with help from its predecessors, but also from the cultural environment it belonged to.

Gardner (1997) offers both philosophical and historical perspectives in his study of the overhead projector, by looking at how this tool evolved from earlier inventions, and investigating how the art and technology behind this tool were being interacted with well before it came to be scientifically understood. First, the history of the overhead projector is traced back to the magic lantern, which initially served the purpose of entertaining children. The lantern in turn influenced the creation of devices such as the slide projector and the epidiascope, the latter created to project images of book pages on a screen. According to Gardner, the origins of technology lie in social values and cultural needs. Even though the technology was in place for the overhead projector to be created decades earlier, it didn’t appear until educators valued visual as well as verbal input, and the financial resources were in place for this educational technology to be purchased in schools.

The Tel-E-Score (1954)

According to Kidwell, Ackerberg-Hastings & Roberts (2008), overhead projectors were initially used not in classrooms, but in bowling alleys. They assert that the ‘Tel-E-Score’ was used to project written bowling scores on screens at the head of the alley. The educational use of devices such as the overhead projector was brought about by a need for greater classroom efficiency. However, Kidwell et al. claim that this initial use of the projector as an educational tool did not take place in a traditional school setting, but rather in a US military classroom. At the onset of World War II, thousands of new recruits were in need of technical training, and many had little education. Kidwell et al. explained that the US government provided special attention and funding for the overhead projector during this time. This led to improvements in the production of overhead projectors such that they became sturdy and inexpensive enough to be brought into the ordinary classroom. Kidwell et al. recognize cellophane, which was invented in 1912 and used later in the making of inexpensive transparencies, as a key contributor to the success of the overhead projector. It appears then that the overhead projector is a product of its culture, influenced by the popularity of bowling and the need for efficient teaching during World War II.

Prior to the war, in the early part of the 20th century, an interest arose in using visual media in the school (Reiser, 2001). This may partly be attributed to lantern slide projectors and stereograph viewers that were used in some schools during the second half of the 19th century. The growth in the ‘visual instruction movement’ during the early 1900s is evidenced by the establishment of five national professional organizations for visual instruction, the new publication of five journals focusing on visual instruction, the design and implementation of visual instruction courses in more than twenty teacher-training schools, and finally the development of a bureau of visual education in at least twelve greater urban school systems in the United States.

Following the war, the combination of aggressive marketing and government grants brought about the proliferation of the overhead projectors in school classrooms (Kidwell et al., 2008). The appeal for educators was that the projector could meet both pedagogical needs and improve classroom management, as this new tool now enabled teachers to remain facing unruly students while writing down important information for the students to read and/or copy. Furthermore, Kidwell et al. mention ‘projectuals,’ innovative teaching aids created specifically for the projectors, such as the iron filings in a bag of fluid that, when used with magnets, could help students visualize magnetic fields. These devices made it possible to engage students by presenting the material in an exciting way.

Gardner (1997) considers the overhead projector to be a system comprised of various technological components, each of which can be traced back to ancient times. The idea of showing images on a screen dates back to the camera obscura of Ancient Greece, and small mirrors were first used in Ancient Egypt. These technologies were later combined during the Renaissance period, as artists used a portable camera obscura with an angled mirror to view subjects and trace their outlines on to paper. Gardner emphasizes the understanding of technology through interaction and exploration with various materials that were behind the projector, and that this knowledge precedes the scientific understanding that helps to create it. “Copper was used for ancient weapons and cooking pots, glass for ancient ornaments, windows and containers, mirrors for personal adornment, fans for personal comfort, windmills for pumping water and grinding flour: science and technology always have their roots in practical techniques, in the arts and crafts, in the universal human activities which keep our bodies and souls together” (Gardner, 1997, p. 19). Gardner offers a materialist view of the roots of science and technology, one that he feels deserves greater recognition.

Although the overhead projector was a popular instructional tool in the classroom, as proven by its aforementioned proliferation throughout schools in North America post World War II (Kidwell et al., 2008), not all scholars believe that the students’ learning experience was improved by the adoption of this device. Knowlton (1992) asserts that although tools like the overhead projector may overtly contribute to student learning of course content such as Math, they also play a role in providing the students with an underlying education via the pedagogical practices themselves. This education includes “…lessons in power and authority, lessons in order and disorder, lessons in what counts as knowledge, who counts as a source of knowing, (and) what is thinking” (Knowlton, 1992, p.22). Knowlton claims that tools used in the classroom could imply a sense of teacher control or authority, even though the teachers themselves may say otherwise. The overhead projector is specifically identified as such a tool by Knowlton, based on how it affects the power dynamic in the classroom. First, light from the projector reveals knowledge at the front of the room, and the light is provided by the teacher, who stands illuminated above the students sitting in the dark, and who is closer to the information than them. Knowlton further adds that the information from a projector is delivered in a bodiless state and therefore considered to be inclusive of all perspectives, unlike delivery of material from a teacher, whose perspective is limited. Finally, the use of a projector enables teachers to move more quickly through material, avoiding students and their questions by cutting out distractions and anything that may slow down the information progress.

In order to change this classroom environment, Knowlton (1992) claims that teachers should turn on a few lights while using the overhead, shut down the projector intermittently to discuss the material and/or take question breaks, and limit the use of the overhead or use other mechanical means of information delivery such as handouts. Advocates of this philosophical view of the overhead projector would likely agree that while this tool may have increased teaching efficiency and the students’ acquisition of knowledge, at the same time it may have increased the perceived distance between students and the knowledge material , as well as their inability to be active participants in the learning process.

The overhead projector may never have come to exist in the school classroom if it was not for an emphasis on visual input in education, combined with the development of this instructional tool during World War II. The overhead projector has influenced the way teachers prepare for and present the class material, as well as the way students experience learning during instruction. Although there has been some criticism of the projector as a teaching tool, it is still the preferred medium of many educators. Although not the first type of projector used in classrooms, this particular device shifted projector technology from the occasional to the mainstream form of instruction.

References:

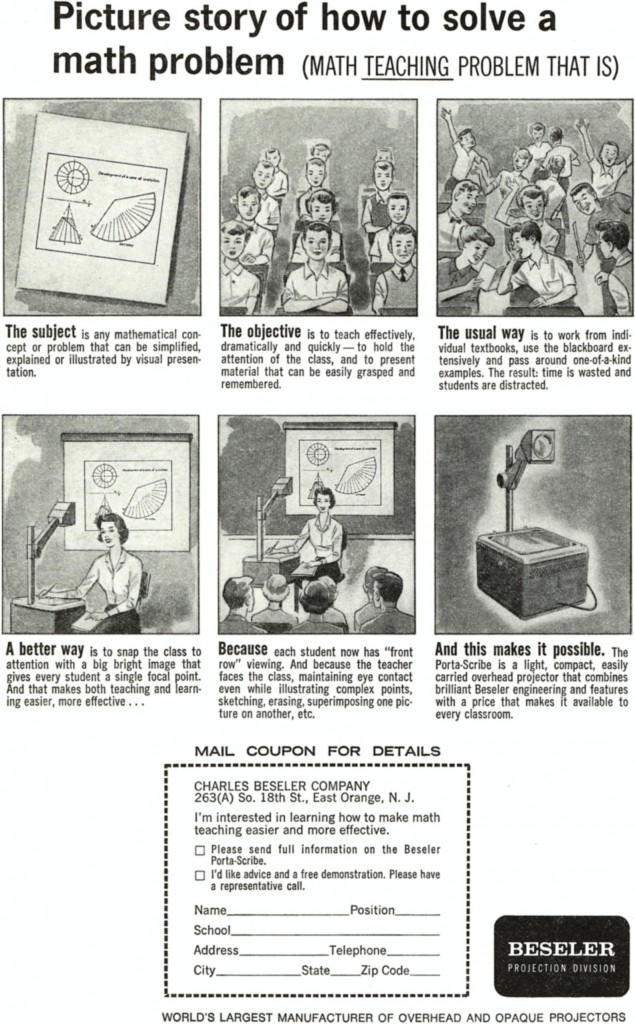

Charles Beseler Company (1965). Picture story of how to solve a math problem [Advertisement]. The Mathematics Teacher, 58(4), 365.

Gardner, P.L. (1997). The roots of technology and science: A philosophical and historical view. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 7, 13-20.

Kidwell, P. A., Ackerberg-Hastings, A., & Roberts, D.L . (2008). Tools of American Mathematics Teaching, 1800-2000. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

Knowlton, E. (1992). The hand and the hammer: A brief critique of the overhead projector. Feminist Teacher, 6(2), 21-23, 41.

Reiser, R.A. (2001). A history of instructional design and technology: Part 1: A history of instructional media. Educational Technology Research and Development, 49(1), 53-64.

Tel-E-Score [Online image]. (1954). Retrieved October 20, 2013 from http://www.flickr.com/photos/alcue/2677060383/

Interesting to read that the overhead projector was not put into production until the culture determined that verbal and visual input were of use together. It seems that now, at least according the arguments we read by Kress and Bolter, that the visual is challenging for supremacy over the written. Perhaps the verbal and the visual appeal more to and better engage the digital natives we see in our classrooms. Thanks for the snapshot into the overhead projector. With the inclusion of LCD projectors and document cameras etc., I suspect we have move further along the continuum and now emphasis the visual and verbal even more. However, as I think about it, these technologies also allow for strengthening visual and textual affordances as well.

Thank you so much for this…the most underrated technology piece ever! I also appreciate the you discussed the overhead as a tool of power. Given our deference to it, the person using the overhead becomes an expert. Silhouetted by the lamp, above the students, it gives automatic authority. Thanks again.

Whether he remains in Spain or looks to seek regular football elsewhere, a player of Torres ability could be an interesting option for some of Europes top clubs.