Introduction

Having learned how to write before computers and spellcheck, I often tend to take my knowledge of spelling and grammar for granted. On my way through elementary school I learned to print neatly, capitalize letters, put a finger-space between words, and to insert a period at the end of a sentence. A paragraph is indented, and there is a clear difference between their, there, and they’re. The art of proper grammar, punctuation, and spelling make reading much easier and definitely much more enjoyable. The manipulation of text and punctuation, such as adding brackets or italics, makes skimming articles and books for information a much quicker process.

For this paper I will give an overview of the origins of word separation and punctuation, and how these finer points of writing have led to the writing concepts we use today.

In the Beginning: How it was written

Writing was originally developed to satisfy a need to transcribe the sound of speech. It is a graphical representation of sounds that refer to the spoken word or to the sounds we here when someone speaks, though they do not directly reference the actual meaning of the word. For example, the word c-a-t does not tell the reader what a cat is, nor does it visually represent a cat, it is merely three letters put together which provide the reader with a pre-learned image of what a cat looks like. When listening to the sounds of speech one does not hear naturally inserted pauses between each of the words. The syllables of speech tend to flow smoothly into one another with only subtle pauses used for expression or at the ends of phrases.

Runes

Jelling stone inscribed with runic writing, raised by King Gorm the Old as a memorial to his wife, Queen Thyre.

Courtesy of the Royal Danish Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Copenhagen

The Runic alphabet was a writing system used from the 3rd century to about the 17th century AD. It is composed of angular symbols and written from right to left and possibly influenced by the Latin alphabet that existed in the 1st century BC. Several varieties of runic script existed in northern Europe before 800 AD. The Anglo Saxon runic script originally contained 28 letters, and increased to 33 after about 900AD with letters that more closely represented sounds of Old English (Encyclopaedia Britannica Editorial Division).

During the early sixteenth century in Liberia, a “form of phonetic syllabary transcription was developed…using polysyllabic words that were transcribed syllabically without word separation, diacritical’s, punctuation, or the presence of initial capital forms” (p.4) In ancient Greek and Roman books, which used a similar style of writing, “the reader encounters at first glance rows of discreet phonetic symbols that have to be manipulated within the mind to form properly articulated and accented entities equivalent to words” (Seanger, 1997, p. 5). At this point, syllables were separated with points, spaces, or a combination of the two together. Another common symbol that was used for separation in early Latin and Greek texts, was the hedera. It resembles a decorative ivy-leaf, which signified a break between words, syllables, or paragraphs. The use of these symbols to separate words did not make it easier to track the phonetic components of the words and syllables when reading aloud, and actually made silent reading near impossible. In addition, the phonetic components of the words were inconsistent in their meaning and understanding, making reading instruction a necessary component of oral recitation.

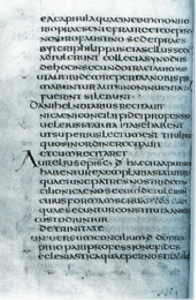

Scriptura Continua

Scriptura continua was a common writing practice during the classical and early medieval periods which involved writing words continuously with one another with no spaces  between them. This style of writing was directly transcribed from speech with the intention be read aloud. Scriptura continua only became possible when the “Greeks adapted the Phoenician alphabet by adding symbols for vowels” (Seanger, 1997, p. 9). The addition of vowels allowed for “the reader to identify syllables swiftly within rows of uninterrupted letters” (Seanger, p. 9). Greece was the first civilization to utilize scriptura continua with the Romans following several centuries later. Though the Romans had adopted the letter and vowel forms from the Greeks, they continued to utilize interpuncts and word separation for about six more centuries when they finally made the change to scriptura continua.

between them. This style of writing was directly transcribed from speech with the intention be read aloud. Scriptura continua only became possible when the “Greeks adapted the Phoenician alphabet by adding symbols for vowels” (Seanger, 1997, p. 9). The addition of vowels allowed for “the reader to identify syllables swiftly within rows of uninterrupted letters” (Seanger, p. 9). Greece was the first civilization to utilize scriptura continua with the Romans following several centuries later. Though the Romans had adopted the letter and vowel forms from the Greeks, they continued to utilize interpuncts and word separation for about six more centuries when they finally made the change to scriptura continua.

Silent Reading and Word Separation

Word separation and silent reading went hand-in-hand. Early in the medieval period “the scriptura continua format of ancient manuscripts changed as space began to be introduced between words” (Seanger, p. 26). By placing spaces between words, silent reading became possible due to the fact that it is “physiologically easier [mentally group letters] when individual letters are framed by space so as to be distinct one from another” (Seanger, p. 29). Spaces between words were followed by the need to organize writing into “idea-unit-like segments” (Olson, D. R., Torrance, N., & Hildyard, A. (Eds.)., 1985), otherwise recognized as sentences.

Punctuation and Grammar

Periods, commas and colons were among the first punctuation marks to appear in writing, in their various forms. Punctuation, when skillfully deployed, provides considerable control over tone and meaning both in oral speech and in writing. From and early age, children are taught to use correct punctuation within their writing as it makes for easier reading. Punctuation, as it is used today, affords a more continuous flow to reading both  out loud and silently. It allowed the reader to scan the page, determine word unites, pace, and prepare for phrase endings. As silent reading became more popular and was more closely associated with knowledge, education, and socioeconomic class, understood usage of punctuation became more widespread.

out loud and silently. It allowed the reader to scan the page, determine word unites, pace, and prepare for phrase endings. As silent reading became more popular and was more closely associated with knowledge, education, and socioeconomic class, understood usage of punctuation became more widespread.

English was not originally a prestige language in England until at least the end of the 14th century when Chaucer made his mark is writing. The church, schools, and universities had all conducted their lessons and business in Latin until this point, until the Norman Conquest in 1066 when the official language began to change to Anglo-French, and finally to English between 1258 and 1362 (Curzan & Adams, 2006). English grammar tends to develop closely alongside of the first dictionaries in the late 1500’s, where prescribed pronunciation also began to make appearances.

Implications for Literacy and Education

Though I have only included a brief history of writing and it’s progression through the times, it is interesting to note that there has always been a human need to organize, record, and communicate our thoughts in some way. In ancient times, the ability to read and write became a measure of socioeconomic status, as it became accepted that those who could read and write belonged to an elitist class who had attended school, and had knowledge of literacy, mathematics, and communication.

Today we send our children to school to learn literacy in new ways in an effort to encourage growth and the ability to communicate within our global community. The printing and cursive writing we learned so well as young students ourselves, are slowly on their way out, while new technological abilities for typing, voice recording, and, drawing, are on their way in for students to learn at a much earlier age. Our students are growing up in a global community where there is a great need for learning literacy in its many forms – old and new. The key is to teach our students to communicate well with acceptable language, punctuation, grammar, and writing skills to ensure that they will have the abilities to evolve along with “writing” as it evolves to it’s next layer of communication.

For Fun…

This is a link to a tool that translates English text to Rune. Simply type in your text and click the ‘translate’ button.

http://www.bmeijer.com/fun_stuff/runic_translator/

Works Cited

Curzan, A., & Adams, M. (2006). How English Works: A Linguistic Introduction. New York: Pearson.

Encyclopaedia Britannica Editorial Division. (n.d.). Runic Alphabet. (Encyclopaedia Britannica) Retrieved 10 18, 2013, from Encyclopaedia Britannica: http://britannica.com

Olson, D. R., Torrance, N., & Hildyard, A. (Eds.). (1985). Literacy, Language, and Learning: The Nature and Consequences of Reading and Writing. London: Cambridge University Press.

Seanger, P. (1997). Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading . Stanford: University Press.