Note: This is the first of three articles. For the extended original article see LinkedIn. The forthcoming posts will focus on (dis)advantages of a negative income tax, and on the implementation of a negative income tax in Mongolia, respectively.

Redistribution as Constitutional Obligation

According to Article 6 of the Constitution of Mongolia the existing wealth concerning land, its subsoil, forests, water, fauna and flora and other natural resources belong to the Mongolian people and every Mongolian citizen should participate in it. In order to achieve this goal, the Constitution provides for the development of a “social market economy” largely based on Western models in which the creation of a “welfare state” plays a central role.

The necessary revenues are to be obtained primarily through the development of mineral resources but also through the collection of legally established taxes general following Article 16, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution. And as in other countries too, taxes are levied on different sources of income generation, assets and income use needed for the functioning and development of a modern state.

However, only a fraction of Mongolians participate in the growing prosperity of the country. And therefore the redistribution of tax revenues to needy domestic citizens is one of the pillars of a welfare state. Pursuing this goal a “Negative Income Tax – NIT” is a viable and promising solution to the challenge of how to achieve such redistribution.

“Expanding” vs. “Mature Economies”

In order to get access to the right and task adequately approach it is useful to distinguish between fully developed, “mature” economies and “expanding” ones which are in the set up, the development and the growth phase. To make this clear, the most important characteristics of mature economies are listed below:

- Aging society as well as aging employees (see http://world.bymap.org/MedianAge.html),

- High average level of prosperity (see http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=BLI),

- High capital stock (see http://www.unido.org//fileadmin/user_media/Publications/Research_

and_statistics/Branch_publications/Research_and_Policy/Files/Working_Papers/2009/WP%2015%20Public%20Capital,%20Infrastructure%20and%20Industrial%20Development.pdf), - Complete degree of saturation in consumer goods and high degree of saturation in goods of upper demand (see http://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/marketsaturation.asp),

- Low growth rates concerning the gross national product (GNP) (see http://data.worldbank.

org/indicator/NY.GNP.MKTP.KD.ZG), - Increasing “distribution struggles” between “poor” and “rich” (see http://www.economist.com/node/7055911),

- Well developed public infrastructure (https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/eb201602

_article02.en.pdf), - Well qualified and highly skilled employees (see https://www.oecd.org/g20/summits/toronto/G20-Skills-Strategy.pdf),

- Expanding share of under-qualified unemployed and no-more-working retired people (see https://www.forbes.com/sites/thecollegebubble/2014/08/15/overqualified-and-underemployed-the-job-market-waiting-for-graduates/#85b78704f67d),

- Intensifying relocation of the production of goods and services of lower and middle technical know-how levels abroad (see http://reports.weforum.org/global-competitiveness-

report-2015-2016/country-highlights/), - Income spreading within different employable groups of working age (see http://www.ilo.org/ wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/documents/publication/wcms_243961.pdf).

Undoubtedly Mongolia belongs to the expanding group of economies and therefore an encompassing and integrated concept of tax and social transfer system should or maybe must have quite another architecture and design than in mature economies.

The Functioning and History of NIT

In principle, NIT represents the logical-consistent continuation of the tax rate into the area below the subsistence minimum which is defined by the state and which is usually not subject to taxation. In this way, below the minimum subsistence level a tax is not deducted from zero but a negative amount which can be interpreted as a positive transferable income to the taxpayers/recipients concerned.

In order to illustrate the functioning of NIT here the following example: Assuming the Government would draw the income line at 10 million MNT per year and the NIT-rate is 50 percent. If the taxable/needy person – however one might define them – has no income at all, he/she would receive 5 million MNT – that is, 50 percent of the amount by which his/her income fell short of 10 million MNT. If the taxable/needy person earns 4 million MNT, he/she would get 3 million MNT from the government – again 50 percent of his/her income shortfall – for a total post-tax income of 7 million MNT [(10 – 4) * 0.5 = 3; 4 + 3 = 7. So as his/her earnings rise, his/her post-tax income rises too, preserving work incentives mainly basing on the drawn income limit and the tax rate.

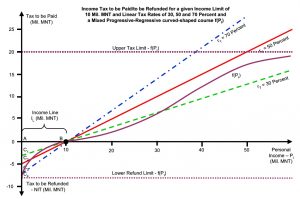

The functional relationships between personal income, a given income limit and varying tax rate are shown in the following chart for a subsistence minimum of 10 million MNT and tax rates of 30, 50 and 70 percent. The areas forming the respective triangles ABC1, ABC2 and ABC3 represent the monetary redistribution volume of NIT. Additionally, there is represented a tax-line for a curve-shaped course f(PI) with an upper tax limit of 20 Mil. MNT and a lower refund limit of 8 Mil. MNT. In this case, the redistribution volume corresponds to the area ABC4.

This effect is very different from many social welfare programs, in which a household either receives all of a benefit or, if it ceases to qualify, nothing at all. The all-or-nothing model encourages what social scientists call “poverty traps,” tempting the poor not to improve their situations.

In summary, the amount of individual NIT-entitled depends mainly on following influencing factors and correspondingly available information whereby the precisely prepared tax-relevant data in Mongolia are playing a very prominent role:

- the available volume of the redistribution mass, which can be roughly determined from the amount of all government revenues minus the necessary current consumption and investment expenditures (Government share),

- the absolute level of the defined subsistence minimum,

- the corresponding tax function/tax rate and

- the number of eligible persons who can be determined as the resultant of the aforementioned influencing main variables.

For this purpose, precisely prepared tax-relevant data are required which are still largely missing in the Mongolian tax administration.

The NIT-concept was already mentioned by the mathematician A.-A. Cournot as „impôt négatif“ 120 years ago and taken up again and elaborated in detail by Lady J. Rhys-Williams in the fifties of the last century, at the time called „social-dividend-type“. But the NIT really was known by the publication of the famous American economist and Nobel Prize winner Milton Friedman, who introduced this concept in his book “Capitalism and Freedom”, (Friedman, Milton,, Capitalism and Freedom, University of Chicago Press 1962). In this book Friedman acknowledged that some form of welfare was necessary in capitalist societies and that the state should play an important role in its provision.

Robert Moffitt noted another advantage of this instrument over other forms of state assistance: “No stigma attaches to the NIT.”( Moffitt, R. A., The Negative Income Tax and the Evolution of U. S. Welfare Policy, Journal of Economic Perspectives Vol. 17, 2003, 119 – 140, p. 124). It is noteworthy that just in the motherland of capitalism, the United States of America, experiments on NIT were carried out in the sixties and seventies of the last century. Although the results were fuzzy, probably because so many other factors were in play, the public reporting was tendentious and biased from the beginning. Presumably this attitude goes back to the deep-rooted self-understanding of American citizens towards their state which should intervene (even financially) in as few private matters as possible.

About Ullrich Andree

Dr. Ulrich F. H. Andree is a Visiting Professor at National University of Mongolia NUM

and public sector consultant.

Follow

Follow