By Hongorzul Bayarnyam & Mendee Jargalsaikhan

All Starts with the Kindergarten Teacher

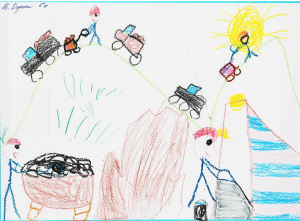

It was touching to see the paintings of kids at the 123-rd kindergarten of Nalaikh District. In their imagined world, all coal miners had safety helmets with flashlights, just like in the drawings of Yesugen and Munkh-Zorig. With the kindergarten’s limited resources, Director Dolgorsuren Unurbayar developed a little classroom for her kindergarteners to learn about the mining. In fact, this little mining world inspired many young artists to share their reflections and imaginations.

If There Were a Museum,

Ms. Dolgorsuren would bring her kindergarteners to the museum; as a result, many of 386 kindergarteners would beg their parents to get an annual pass to have fun with their friends and play with those yellow toys, donated by, for example, Wagner Asia or Komatsu.

All classes of kindergartens and schools of Nalaikh District would bother the museum to de-conflict their field trip schedules. Many schools in UB would plan to visit the museum to learn more about mining, but also escape from the polluted air and congested traffic.

Nalaikhers would often head to the museum to learn about their community, to stroll through the memorial garden, and to check some rotating exhibits or cultural events – since the museum is safer than the aging cultural centre of the district.

People, who had past connections (parents worked and lived in Nalaikh), would love to stop by the museum once in a while to recall their memories looking at photos, equipments, and old train station. Some would bring their children, grandchildren, or friends to share the memories of the good old days.

Curious undergrads or graduate students pack their lunches to spend several hours learning about the history of industrial mining, railroad, and labs – many of which donated by big mining corporations. Students of the German Mongolian Institute for Resources and Technology (GMIT), which is located in Nalaikh, would be the first ones to run these labs.

A tour guide, who accompanying their tourists to Gorkhi-Terelj National Park, Chinggis Khaan Monument, Tonyukuk Monuments, and/or businessmen, who driving to south through Nalaikh, would suggest to stop for a coffee, a photo (old station, train, miners), wi-fi and even a quick tour at the museum. All remember there two miners’ photo station near the gate – for snapchats, Instagram, wechat, Facebook – always gets lots of likes.

The most challenging people would be veterans, who worked in Nalaikh. They would suggest different settings, events, and improvements to pass along success stories of Nalaikh. They would be proud of Nalaikheers – who saved the mine from the saddest place.

If There Would be a Museum,

The surrounding area for salvaged administration building, mining shaft, railroad station, and road (with 5 meters sideways) would be enough for the development of the Museum, which would serve as educational, historical, and cultural purposes.

The three-story administration building would house the main exhibits while shafts could become the primary viewing area for tour-guides and visitors.

The ideal museum and educational centre could consist of the following sections.

- Industrial Mining History Section – tells the history of the industrial mining development through different stages of Nalaikh coal mine from 1905 to 1990. Here people could easily visualize how the coal mining industry evolved in Mongolia and how the mine helped building a glass factory in Nalaikh and many other light factories in Ulaanbaatar.

- Nalaikh History Section – presents facts about Nalaikh, tells story of the emergence of new labor force, and provides insights on multiethnic culture, especially, since Nalaikh was the first experiment of providing settlements for Kazakh nationals.

- Mining Rescue & Artisanal Mining Section – speaks about how mining rescue unit was established and artisanal mining evolved along with stories of evacuation efforts.

- Railroad History Section – using the only surviving railroad station (with a locomotive and restaurant train), narrates the railroad history of Mongolia since all starts from Nalaikh to carry the coal to the first power plant.

- Educational and Cultural Section – could eventually accommodate public lectures, rotating exhibits (even paintings of kindergarteners or photos of skilled photographers), laboratories (e.g., earth science, mining engineering, environmental awareness), and even 3D theatres.

- Outside Section – the renovated railroad station, photo stands, memorial garden, underground shafts (one for artisanal mining, the other for industrial mining), and walkways to the shafts and viewing areas). The funniest part for all would be walking on the railroad rails – since there is no train is coming; taking photos at the train station; and the funniest (weirdest) sign of Nalaikh Museum for a photo at the gate.

Once the museum is developed and items (for exhibits) are collected, more specialized sections could be established.

Costly, Complicated, Scary?

The development, operation, and maintenance of the museum and educational centre is expensive, especially, keeping the facility warm through frigid months of Nalaikh is costly.

- The cost must be shared and the development project must be carefully planned.

The project could be easily hijacked by profit-seekers as well as fame-seekers; therefore, it’s complicated.

- The project must be insulated from political and economic interests.

Over 800~1200 artisanal miners work around the abandoned mine; this makes scary place to visit.

- Most of these miners don’t want to see Nalaikh mine disappear and many would join efforts of saving the mine’s history.

A Cradle of Nalaikh Should Be Protected and Remembered

The establishment of Nalaikh Museum and Educational Centre is not for making money, but it is for embracing the cradle of Nalaikheers – who contributed to the development of the industrial mining and the establishment of the multi-ethnic community.

It would show kindergarteners and students that you (Nalaikheers) can correct your past mistakes and preserve the history and culture of your community.

It would show that Mongolians could reclaim the abandoned mines make a place to strengthen your community and share your history (successes & failures) with your guests.

It would show how different stakeholders (mining companies, local authorities, concerned citizens, public officials, and private businesses) work together for the public good.

Of course, the easiest solution is to keep the status quo, which leaves us to show the ‘Losers’ Story’ for kindergarteners – who would only remember their close ones or community members working without any safety equipments in the worst labour condition.

About Hongorzul

Hongorzul Bayarnyam, social and cultural anthropologist, who was born and raised in Nalaikh. Lots of credit should go to Hongorzul, who has been a continuously advocating to preserve the cultural heritage of Nalaikh. Currently, she is working as an external relations and monitoring specialist at the Governor’s Office of Nalaikh District.

Follow

Follow