The visualized work for this research is on

https://sites.google.com/site/etec540manga/home

The rise of manga is not only a Japanese phenomenon, but an international happening. Manga is seen more as a sub-culture than a literal work. While texts are dominant in other printed media (Bolter, 2001), in manga, both graphics and texts play integral rolls in the multimodal narrative story. What makes manga significant from other books or even from Western comic books? What is the role of manga in literacy?

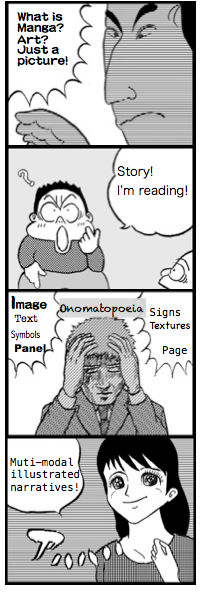

What is Manga?: Illustrated Narrative, Visual Language, Narrative Art…or Popular Culture?

“Japanese manga is a visualized narrative”

(Schodt, 1996 as sited in Murakami and Bryce).

Manga is a term used to describe Japanese comics or their style of artistic expression. In Japan, manga refers to any printed comics including all genres for all generations. Manga combines images and scripts. Like any other forms of visual art and literature, “manga is immersed in a social environment including history, language, culture, politics, economy, gender and education” (Ito, 2005). Recently manga expanded to readers across the world. Especially in the North America, the manga market in 2006 had grown to an estimated two hundred million dollars (Poitras, 2008).

Distinctiveness of Manga from Comics by Ingulsrud & Allen (2009)

1. Graphic and Language

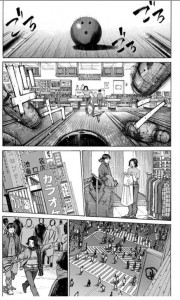

The representation of characters is both “symbolic” (simple) and “iconic” (photograph-like) depending on the characters’ situation, identity and emotional state. While western comic characters are unchanging in image, the same characters are sometimes drawn ironically or in a caricatured way in manga. McCloud (1994 as sited in Ingulsrud & Allen) says that symbolic representations are closer to language. In manga, while the linguistic representation constitutes symbols, similarly, graphics involve symbols.

Japanese language has shaped manga. A variety of Japanese onomatopoeia written in the background becomes a part of the graphics.

2. Presentation and Publication

Variation of panel arrangement—Size, shape and arrangements of images, texts and panels create more expressive effects. Panel arrangement is an essential technique for manga expression.

Narrative and serialized contents—Since the majority of manga is published in weekly or monthly magazines, the manga publishing industry is large.

3. Relationship with other media

The competition between manga and other newer media is not threatening as manga survives in spite of the growth in animation, TV, and the Internet. Manga is a part of media mixing where many television animations and drama programs are based on manga stories.

4. History

The history of manga is original in its early age, at the same time, it is a part of the history of writing technology.

Manga History

Origin and Pre-Manga Scrolls

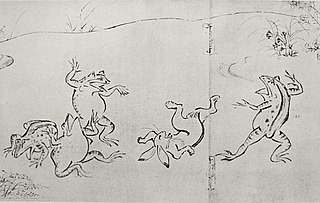

Although the beginning of manga is still controversial between academic researchers, the history is connected with traditional drawings. Researchers find grounds in traditional Japanese pictorial arts for manga’s distinctive graphics (Intgurlud &Allen, 2009). The precursors of manga are associated with the caricatures of people and animals. The oldest is written on the backs of a temple ceiling that was built around 600 CE (Ito, 2005).

Among narrative arts and stories with sequential images, scrolls written around the twelfth century are famous (Choju Giga image ). There are no texts in the paintings, and events are described progressively as the scroll is unrolled from right to left. A limited number of high-class citizens such as clergy and powerful warrior families viewed these scrolls. (Ito, 2005)

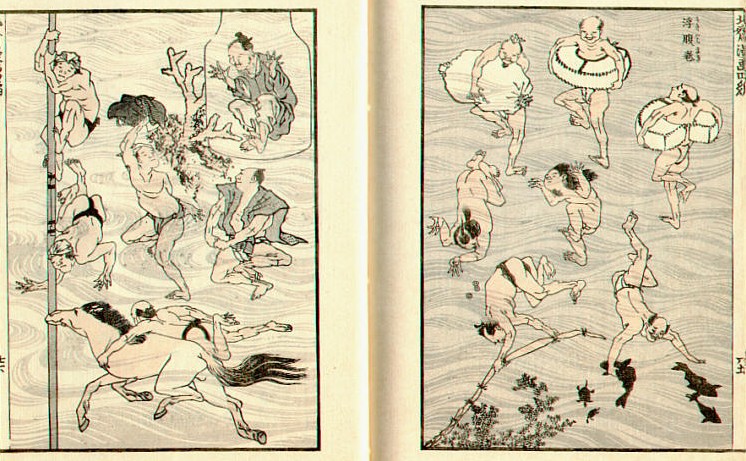

Woodblock Printed Manga

The commercialization of manga started in the beginning of the eighteenth century. The term, “manga” is coined by a Ukiyoe (Japanese woodblock prints and paintings) artist, Hokusai, whose book became a bestseller.

The genre of folk pictures was popular among the urban merchant classes. While the printing press has had a great impact on the history of Western comics, Japanese manga had its first rise with wood block prints instead of movable types (Ingurlud &Allen, 2009) since texts and graphics can be carved on a single page. Because of the large numbers of kanji (logographic Chinese characters), wood block prints were dominant at the time (Kamei-Dyche, 2011). In other words, the technology reflected textual preferences (Ingurlud &Allen, 2009). A lot of woodblock print artists used multiple panels on one sheet, and it became sequential panels in manga. Publishing in Japan expanded during the Edo Period (1608-1868) and a wider audience gained access to manga (Ingurlud & Allen, 2009). Literacy, which had been limited to the elite, gradually became accessible to the urban middle classes with help of the small local schools and private schools (Ito, 2005).

(Ukiyoe images Hokusai Manga)

Besides the single page prints, the influential tradition relating to manga is the “Kibyoshi” books that “braid pictures into a textual tale” (Natsume, 2011).

Modern Civil Rights Movement and Manga

One of the important functions of manga, satire was most dynamic during the civil rights and political reform movement in the Meiji period (1868–1912) (Ito, 2005). “Manga journalism” is pressed on the newspapers and magazines, increasing influence on politics. Western artistic styles are imported rapidly. In this period, the public education system was established, and a greater population gained literacy (Ingkurlud & Allen, 2009) while the regional gap continued.

After the WWⅡ

The rise of manga is primarily in the post-World War time, when influences from America and gifted creators came about (Ingursurd & Allen, 2009). The current manga style started after the war through the publications of manga magazines and works from pioneers such as Osamu Tezuka. Cinemas influenced manga artists for the panel design. Manga gained a rich novel-like story with realistic and graphic pictures (Ito, 2005). With development of the printing technologies, such as zinc relief printing, copperplate printing, lithography, metal type, and photo engraving technology, manga became a medium of the masses (Ito, 2005).

Visual and Verbal Effect of Manga

Bolter (2001) discusses that in the print medium, pictorial space and verbal space are opposite and texts subordinate images. Manga is nothing but a print media; yet images, texts, and constitution of pages and panels are all integral part of manga.

The Structure of Manga

- Panels, graphics, and symbols indicate

-movement and sound

-tactile qualities

-emotional states of the characters

- Graphic onomatopoeia expresses auditory and tactile information.

- Qualities of texture and non-linguistic graphic symbols represent the characters’ movements. Cohn (2007) defines their visual grammar as “Japanese Visual Language”.

- Speech balloons develop dialogue

- Variation of panels in size, shape and number creates a literacy effect of “a grammatical block analogous to a conventional sentence”(McCaffery and Nichol, 2000) .

These effects are similar to the effect that Bolter (2001) describes “the word transforms the picture into a writing space, while the picture invites the words becoming images or abstract shapes rather than signs.” Ingulsrud & Allen (2009) stresses that graphics and languages are interrelated, that is why manga cannot be read aloud. Therefore, the language component alone is insufficient to understand the text.

Criticism

Although positive effects of manga have been recognized gradually, manga has been claimed to be harmful because of the extreme description relating to violence and sexual topics. In Japan, Tokyo Metropolitan Government controls some extreme manga by the regulation act (Inoue, 2011). The decline of book reading in Japan is another issue. Critics associated comics with the hazards of young people’s lack of literacy skills or their commitment to crimes (Inculsurd & Allen, 2009).

Manga Reading and Literacy

- Strategies for reading manga

It is claimed that manga requires multimodal reading skills and a sharp critical inquiry stance (Schwartz & Rubinstein, 2006), because meaning is conveyed at different levels, such as layout of pages, illustrations, words, and scripts. Ingulsurd & Allen (2009) studied Japanese junior and senior high school students in order to investigate their manga reading strategies. Their research in tracking a reader’s eye movement finds that most of the readers focus on the speech balloons and texts when reading manga. On the other hand, the readers responded that their main reason to read manga was because of its graphics. Learning the panel order for reading requires much practice and experience.

- Communicty of practice

Unlike school literacy that is formally taught, readers gain manga literacy informally from other readers such as friends and older siblings. Children borrow and lend manga or they read manga together at home, sharing the same interests. Ingulsurd & Allen (2009) finds Wegner’s (2011) notion of “the communities of practice” in manga literacy development. They discusses, “manga literacy is scaffolded by individual agency and other readers”. In fact, comics are important shared texts for young children. On the other hand, their research result suggests that the readers, especially older students, tend to solve difficulties in reading by rereading, rather than asking someone, and it is against the concept of “community of practice”.

- Cognitive effect (Murakami & Bryce, 2009)

The researchers suggest that multimodal information presented both in verbal and non-verbal format enhances readers’ memory. In addition, illustrations written with thematic focuses promote readers’ understanding. Effective learning occurs by “multiple layers of information in context and project a focused content”.

- Multimodal literacy and visual literacy

Manga literacy involves understanding and responding to the multiple modes used in forming meaning. One of which is the visual literacy that is interpreting graphic images (Nakazawa, 2005). Schwartz & Rubinstein (2006) believe that manga literacy can be applied to not only school literacy, but also other media in enhancing literacy that hyper media requires us. They encourage manga use for development of analytical and critical visual texts. The multimodality of manga texts “extends the traditional notions of text and literacy” (Carrington, 2004, as sited in Schwartz & Rubinstein).

Education

It was only in the 1980s when school libraries in Japan started a positive discussion revolving manga. There had been reluctance for students’ manga reading among parents and educators. After the 90’s, more teachers had tried to use Manga in Japanese classrooms (Inoue, 2011). Educational benefits were carefully considered, and the Japanese government officially accepted the use of manga in the classrooms. Manga is by nature understandable and motivating (Nakazawa,2005). Classic literature in the manga format and students’ comic creation for literacy education are common outside of Japan as seen in “Comic Book Project”.

- Manga as a study aid

Gakushu Manga (learning manga) has been one of the most popular holdings as a study aid, for history, science, and classic literature in Japan. These manga books are stimulating children’s curiosity for studying. Therefore, manga has been a primer or supplement for children to study and read more on school subjects. (Inoue, 2011).

- Japanese government guidance

The guidance indicates elementary school and junior high school manga use for each subject.

Elementary school—Students are able to use manga as learning materials and students can express their opinion by using manga.

In high school — official math textbook explains the concept using manga.

Criteria of Manga at school libraries –SLA criteria to select Manga(1988)

- Manga literature outside of Japan—Pop culture, after all?

Educational manga has also been created outside of Japan, as seen in “Manga Shakespeare”. While the series won awards from publishers, they receive critical claims questioning simplification and over pragmatic means. Moreover, Grande (2010) argues the problem of “double access” to Shakespeare that the series gained: “pure gaze” that is a high-culture of traditional British literary studies and “popular gaze” that is a new young popular culture. This division apparently rooted in the position of manga in academic and educational world.

Conclusion

Manga in Japanese educational environments focuses more on breaking down the subject matter than on literacy education. More analysis on multimodal literacy development with manga should be examined. In the late age of print that is “visual rather than linguistic” (Bolter, 2001), it is natural that manga has attracted readers all around the world. Multimodality and unity of text and images overlap with hypertext writing. Manga is rooted in the print medium, yet as it moves technologically beyond print, the manga characters move across mobile phones, the Internet and game devices fuelled by popular demand (Ingulsrud & Allen, 2009).

References

Bolter, Jay David. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print [2nd edition]. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cohn, N. (2007). Japanese Visual Language: The structure of manga. In Manga: An Anthology of Global and Cultural Perspectives. New York, NY: Continuum Books. Retrieved, 5 October 2013, from

http://www.visuallanguagelab.com/P/japanese_vl.pdf

Grande,T. (2010). Manga Shakespeare and the Hermeneutic Problems of “Double Access”. Retrieved, 24 October 2013, from

http://ourspace.uregina.ca/bitstream/handle/10294/3091/QueenCityComics-3-Troni_Grande.pdf?sequence=1

Inoue, Y. (2011). Manga as a study aid at school libraries. Paper presented at the World Library and Information Congress San Juan, Puerto Rico. Retrieved from

http://conference.ifla.org/past/2011/214-inoue-en.pdf

Ingelsrud, J. and Allen. K. (2009). Reading Japan Cool: Patterns of Manga Literacy and

Discourse. Lanham, MD: Lexington.

Ito, K. (2005). A history of manga in the context of Japanese culture and society. The Journal of Popular Culture, 38(3), 456-475.

Kamei-Dyche, A. (2011). The History of Books and Print Culture in Japan: The State of the Discipline. Book History, 14 (1), DOI: 10.1353/bh.2011.0008

Keep, C., McLaughlin, T., & Parmar, R. (1995). The electronic labyrinth. Retrieved, 10 October 2013, from: http://www2.iath.virginia.edu/elab/hfl0206.html

Murakami, S and Bryce, M. (2009). Manga as an Educational Medium. The International Journal of the Humanities, 7.

Nakazawa, J.( 2005 ) . Development of Manga (Comic Book) Literacy in Children. Applied developmental psychology: Theory, practice, and research from Japan. Greenwich, Con: Information Age Publishing.

Natsume, F. (2011). Pictotext and panels: commonalities and differences in manga, comics, 37 and BD. Paper presented at the Comics Worlds and the World of Comics: Towards Scholarship on a Global Scale, Kyoto, Japan. Retrieved from

http://imrc.jp/2010/09/26/20100924Comics%20Worlds%20and%20the%20World%20of%20Comics.pdf

Poitras, G. (2008). What is Manga?. Knowledge Quest, 36(3), 49-49.

Schwartz, A., & Rubinstein‐Ávila, E. (2006). Understanding the Manga Hype: Uncovering the Multimodality of Comic‐Book Literacies. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 50(1), 40-49.

Wenger, E. (2011). Communities of Practice: A Brief Introduction. Retrieved, 20 October 2013, from

https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1794/11736/A%20brief%20introduction%20to%20CoP.pdf?sequence=1

It’s nearly impossible to find well-informed people for this

topic, but you seem like you know what you’re talking about!

Thanks