By Byambajav Dalaibuyan

Introduction*

Japan is well known for its lack of mineral resources. However, interestingly, the Japanese domestic mining industry played a crucial role in the nation’s industrialization and modernization in the 19th and the first half of the 20th century. The country even exported gold, copper and other mineral products.

In September 2018, I had a scoping visit to two mine areas closed in the 1970s to explore how these mine sites are maintained as sightseeing and learning centres, as part of a research study funded by the JSPS research fellowship at Centre for Northeast Asian Studies, Tohoku University. In this photo-essay, I will introduce the sightseeing centre and community learning centre of Ashio copper mine and smelter in Tochigi prefecture.

The Ashio mine sightseeing centre

Several groups of school students were having a guided tour. I was told that they were not only students from local areas, but also students from different regions of Japan visiting the mine sightseeing centre. I used a rental car but the mine site is accessible by local train and bus.

From the centre entrance a small mine train transports visitors to the underground mine tunnel. Inside the tunnel, the history of the mine, main activities that miners did in the past, and old machines, mineral samples and products made by copper are presented in different ways.

Since the 1960s Japan opened its door to Western culture, capital and people to depart from an isolated feudal society to a modernized, industrialized society. Because artisanal and archaic methods of mining were prevalent, many mines had been closed or operated with very low productivity at the time. Western mining and mineral processing industry was far ahead. Embracing Western technologies and engineers, some mines in Japan were reopened and increased their output and productivity. Gold, silver, copper, coal and other types of minerals and metals were mined ad supplied to emerging domestic industrial centres and foreign markets.

Outside the tunnels, there were a number of historic displays of equipment, a gallery showing social history of the mine, and souvenir shop.

Mining and environmental degradation

As a source of strategic minerals and foreign exchange, mining was an important industry for the Japanese government during World War I and II. Some mines and smelters continued operations despite deleterious environmental pollution and local community opposition. By the 1970s, most mines had ceased to operate due to high domestic labour cost and depletion of good ore reserves. Importing raw mineral resources became a better alternative for processing plants and smelters.

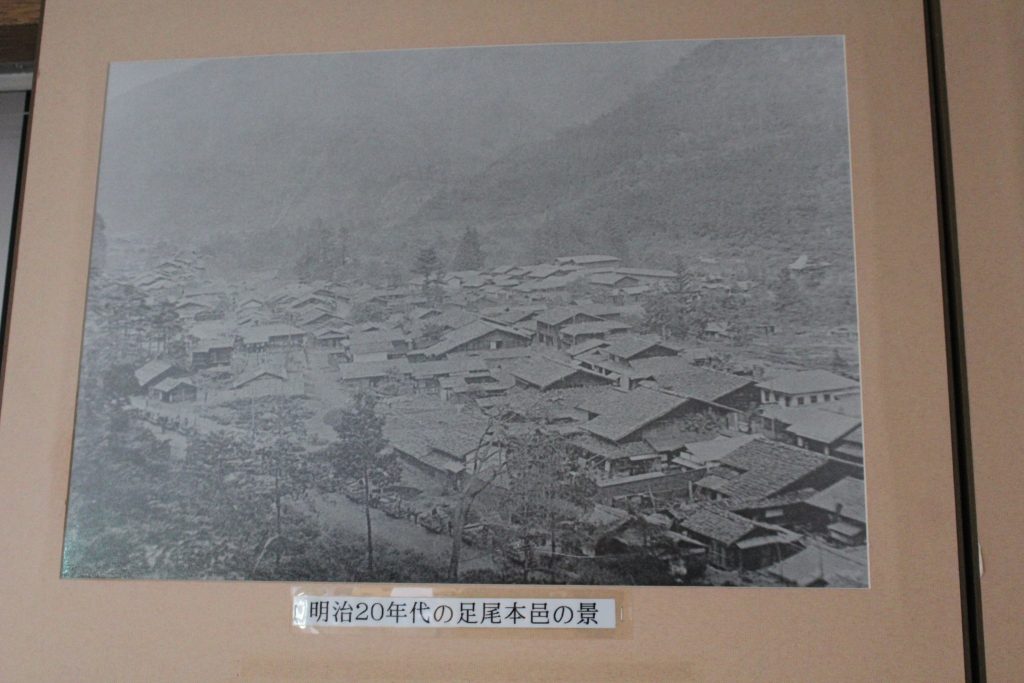

After new exploration and large-scale industrial mining technologies introduced in the 1880s the production rate of Ashio mine increased dramatically to account for 20% the country’s copper export. Wastewater from the mine and its smelter polluted nearby rivers and killed their entire fish population. The mine’s use of timber for construction and as a source of fuel caused the widespread deforestation and barren mountains, increasing the damage from flooding. Toxic emissions from the refining operations of the mine polluted the surrounding ecosystem and nearby communities had to permanently leave their villages. Though some measures were taken by the government and company to reduce air pollution and rehabilitate the landscape toxic emissions from the smelter continued until the 1950s when a facility for collecting sulphuric acid was built. It is estimated that about 2400-3000 hectares of area was affected by toxic emissions.

Ashio was crowded by mining workers in its heyday and saw a massive population outflow when the mine was closed in 1973.

Rehabilitation activities

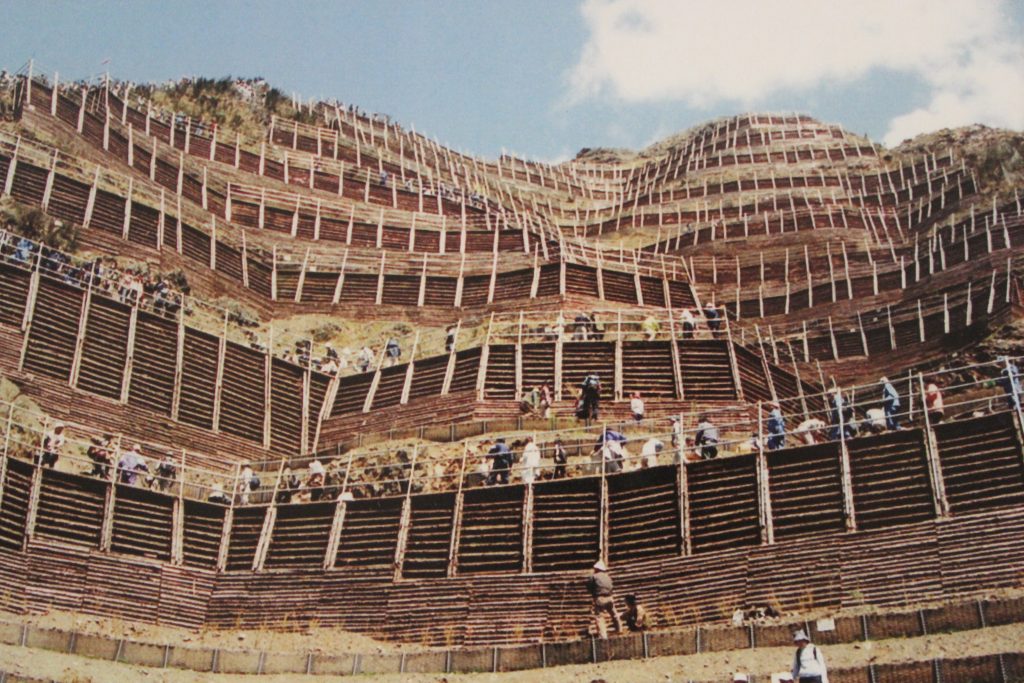

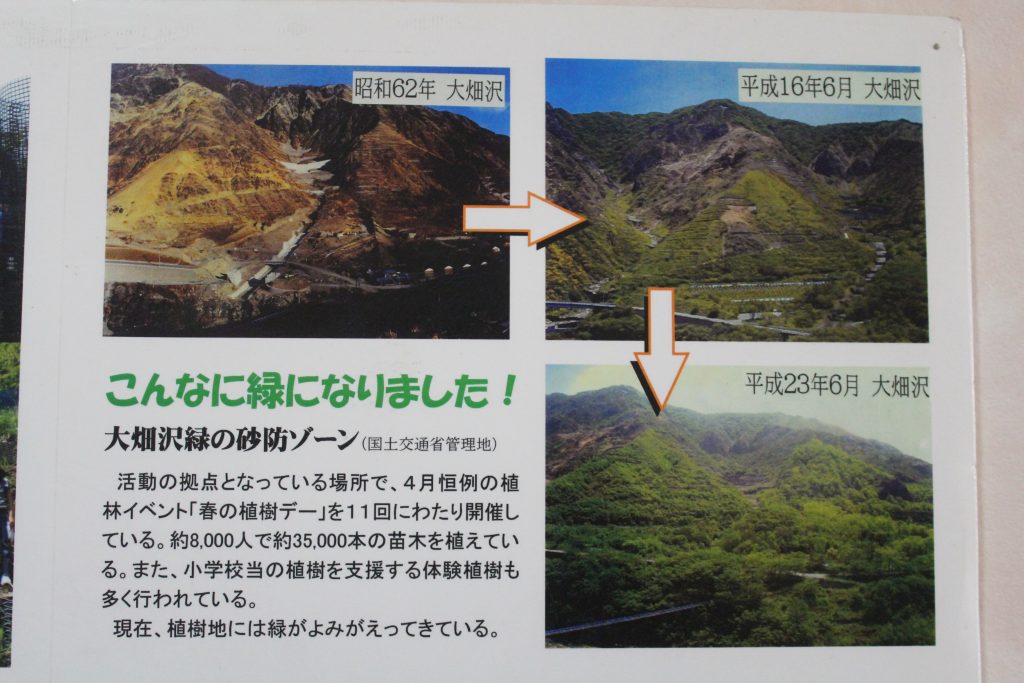

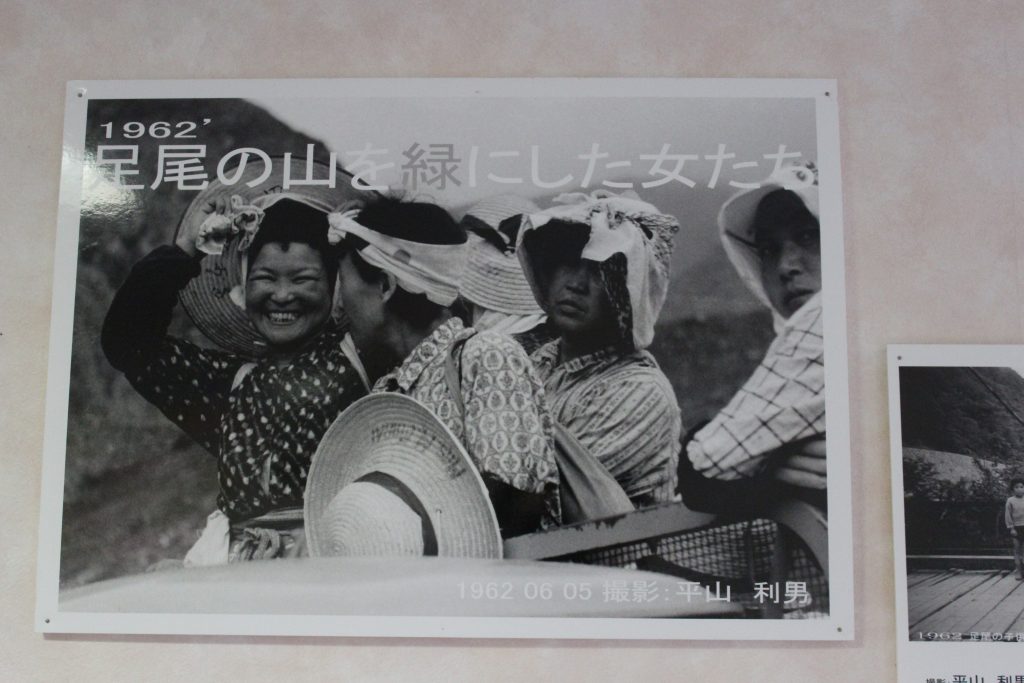

Reforesting the surrounding barren mountains has been a main focus of rehabilitation activities in Ashio. Since the 1960s, government, local communities and volunteer organizations worked hard to reforest steep mountain slopes.

“When we plant trees up in the mountains we also plant hope for the future in our hearts” Wahei Tatematsu

Grow Green Ashio, a non-profit organisation, in collaboration with Ashio town, has managed rehabilitation and public-awareness activities since 2000. It organizes a tree planting day, summer weeding day, and fall observation day to recruit volunteers and maintain their involvement. It also holds the annual Green Ashio Forum to facilitate public discussion about pollution and collective action.

Grown Green Ashio manages the government-funded Ashio Environmental Learning Centre, which aims to enable the public and young generation to learn about industrial history, environmental impacts and rehabilitation activities. The Centre runs environmental research and experience programs for school students and the general public that include learning activities at the centre and tree planting in the mountains. The centre has a mini theatre and training room, photograph exhibitions, and information sections on pollution and restoration.

Rehabilitation activities have achieved improved water quality, prevention from flooding and landslides, significant reforestation, and early signs of natural flora and sauna. However, as the centre staff said, it had been a more than half a century to finally see reforested mountainsides but it was only a half of the area suffered from the mine impacts for a century.

Ashio mine sightseeing centre and Environmental learning centre enables visitors to learn Japans industrial history and technology and environmental and social risks and impacts and provide opportunities to have hands-on experience of environmental reclamation. Their success shows the importance of government-civil society partnership and public engagement and volunteerism.

* In February 2018, a group of researchers, including me, at the Centre for Northeast Asian Studies (CNEAS) of Tohoku University discussed about exploring the life of closed and abandoned mines in Japan. We have had scoping visits to several closed mines, mainly to explore their social and sustainability dimensions. In March 2018, the group visited Kamaishi underground copper mine located in the northeastern coast of Japan. Mining of copper ore at Kamaishi ended by the early 1990s and the owner company had since maintained the mine site. The company produces bottled mineral water from the water collectors inside the mine tunnels. Professor Hiroku Takakura produced a short ethnographic film based on the visit to the mine and interviews with company personnel at the site. A research article by co-authored by the group will be published in Russian. This photo-essay includes one of two mines that I visited in September 2018.

Follow

Follow