By Camille Barras

Previous posts in Mongolia Focus have addressed the issue of women’s political representation, for example concerning the share of candidates in the upcoming elections. Women’s participation as voters is another important facet of women political empowerment. In a post about the 2016 and 2017 elections, Julian Dierkes observed that the number of women voters exceeded men’s in nearly all aimags and districts. Was this just a demographic effect (there are indeed more women than men in the age categories 30-34 and beyond)?

Not only, according to NSO statistics: women’s voter turnout (# voters / # registered voters) was actually higher than men’s by 6 percentage points on average in the 2016 parliamentary election. Estimating voter turnout by gender for each electoral district (see Table 1, estimates for 2016), it appears that this reverse gender gap exists across all electoral districts and holds for several elections, namely the 2016 parliamentary election, and the first round and runoff of the 2017 presidential election (with the exception of Bayan-Ulgii in the two presidential election rounds).

|

Electoral district – 2016 parliamentary elections |

Gender gap (female-male) |

Female turnout |

Male turnout |

|

Bayan-Ulgii |

0.030 |

0.894 |

0.864 |

|

Sukhbaatar (aimag) |

0.040 |

0.839 |

0.799 |

|

Uvs |

0.045 |

0.871 |

0.827 |

|

Khovd |

0.050 |

0.837 |

0.787 |

|

Govi-Altai |

0.057 |

0.831 |

0.774 |

|

Dornogovi |

0.061 |

0.774 |

0.713 |

|

Arkhangai |

0.062 |

0.820 |

0.758 |

|

Dornod |

0.072 |

0.759 |

0.688 |

|

Umnugovi |

0.075 |

0.772 |

0.696 |

|

Tuv |

0.076 |

0.792 |

0.716 |

|

Bayankhongor |

0.076 |

0.844 |

0.768 |

|

Zavkhan |

0.081 |

0.881 |

0.801 |

|

Khentii |

0.084 |

0.819 |

0.735 |

|

Bulgan |

0.085 |

0.797 |

0.712 |

|

Bayanzurkh |

0.092 |

0.751 |

0.659 |

|

Dundgovi |

0.092 |

0.807 |

0.715 |

|

Selenge |

0.093 |

0.776 |

0.683 |

|

Khuvsgul |

0.093 |

0.784 |

0.691 |

|

Uvurkhangai |

0.095 |

0.811 |

0.716 |

|

Orkhon |

0.097 |

0.754 |

0.658 |

|

Songinokhairkhan |

0.097 |

0.759 |

0.661 |

|

Govisumber |

0.099 |

0.826 |

0.727 |

|

Khan-Uul+ Bagakhangai |

0.107 |

0.799 |

0.691 |

|

Nalaikh + Chingeltei |

0.110 |

0.751 |

0.641 |

|

Baganuur + Sukhbaatar (district) |

0.112 |

0.777 |

0.665 |

|

Bayangol |

0.115 |

0.789 |

0.674 |

|

Darkhan-Uul |

0.129 |

0.771 |

0.642 |

[Table 1. Voter turnout estimate: number of (wo)men voters in electoral district / (total registered voters for both genders in district *share of (wo)men in elect. district in year of election) (data: GEC/NSO).]

Reverse gender gap in voter turnout not unique, but sizable

Such “reverse” gender gaps in voter turnout are not exceptional, as in many countries women vote as much or more than men since several decades now – studies notably point out that women have a stronger sense of “civic duty”. Yet the size of the difference in Mongolia seems quite large in international comparison. Also, a hint that this gender gap might even hold in local elections (female turnout in Songinokhairkhan district: 49.4%; male: 41.7%) is rather at odds with evidence that a traditional gender gap (that is, higher male voter turnout) still subsists in subnational elections in other countries.

Why is that the case? While a comprehensive and accurate answer would require further research, it can be said that Mongolia is relatively closer to (but still far from!) gender parity on global average in regard to a number of “structural” indicators that are usually thought to matter as factors of political participation. Going with WEF’s Global Gender Gap Report from the year of the last elections, Mongolia fares indeed better comparatively in terms of economic opportunity but also educational achievement (female/male ratio for labour force participation: 0.84; for income: 0.74; for enrolment in tertiary education: 1.38).

Within-country variation of reverse gender gap

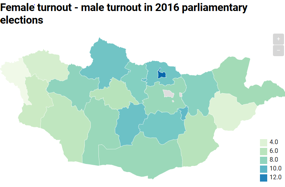

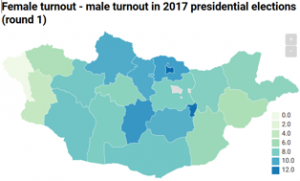

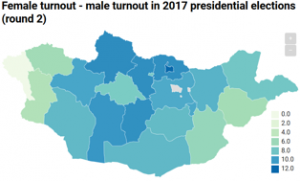

The size of the reverse gender gap varies substantially between constituencies. Eastern and Western aimags have a smaller gap (that is, they are more “equal”) – a pattern consistent across elections, as evident from the maps below. The gap is larger in urban areas (UB districts and secondary cities) and almost reaches 13 percentage points in Darkhan-Uul. It also seems that men’s voter turnout (64% to 86%) has a wider range than women’s (77% to 89%) (2016 election). Places with a smaller gender gap, such as Bayan-Ulgii, actually tend to have a high male turnout rate, rather than low female participation.

[Gender gap based on voter turnout estimates (GEC/NSO)]

The reasons behind these differences between electoral districts in Mongolia are hard to elicit due to lack of data. Rough preliminary analyses limited to socio-economic indicators do not support that either gender differences in education nor workforce integration are at play. A glance at the aimags with the lowest and highest gender gaps in turnout (Table 2) suggests that the gender gap might mainly come from differences in men’s turnout– perhaps logics of (male voters’) mobilization differ across aimags?

|

Voter turnout (estimates) Average of 2016 parliamentary elections and 2017 presidential elections (2 rounds) |

Gender gap (female-male) |

Female |

Male |

|

3 aimags with lowest gender gap (Bayan-Ulgii, Khovd, Sukhbaatar) |

0.03 |

0.73 |

0.70 |

|

3 aimags with highest gender gap (Darkhan-Uul, Govisumber, Uvurkhangai) |

0.11 |

0.72 |

0.61 |

[Table 2]

Will this reverse gender gap persist – and to a similar extent – in the 2020 elections, and beyond? The female-male ratio among registered voters for the upcoming election (52% – 48%) looks identical to what it was in 2016 (which had an estimated 1,003,500 registered female voters and 934,400 male voters). Given the size of the gap in voter turnout and its consistency across elections (2016 parliamentary, 2017 presidential and probably 2016 aimag and soum-level elections), it is quite plausible that this is a structural trend that will hold on the long run. It would nevertheless be worth looking at how the gap has changed in different electoral districts and whether the difference between urban and rural areas has widened or narrowed.

About Camille Barras

Camille is a PhD candidate in Politics and International Studies at the University of Cambridge. Her research focuses on subnational governance and political engagement. Before that, she worked in International Development, and lived in Mongolia for her last posting.

Follow

Follow