By BOLDSAIKHAN Sambuu

Youth abstention is fast becoming a hot topic in Mongolia as the parliamentary elections come right around the corner. This is partly because, in this year’s elections, both major and new parties, such as the National Labor Party, have nominated an unprecedented number of “younger” and “fresher” candidates, all banking on the youth vote. Moreover, various non-partisan NGOs, local and international, are in a buzz of activity, all undertaking projects aimed at raising the youth turnout in June.

As part of such initiatives, with the help of the Zorig Foundation, I have had the opportunity to conduct a modest online survey of 680 respondents between 18 and 25 years old. With this survey, we attempted to gain insights into the most prevalent individual reasons for why some young people decide to vote whereas others do not. The survey was supported by the campaign, “Strengthening Women and Youth Engagement in the Electoral and Political Processes in Mongolia,” which is being funded by the USAID and implemented by the International Republican Institute (IRI) and the Asia Foundation (TAF).

A variety of complex causes influence the electoral turnout of young voters. Factors such as the nature of Mongolia’s current two-party system, the majoritarian bias in the electoral rules, the quality of the election campaigns, and the list of candidates are all arguably important factors that influence the turnout. However, these “systemic” or “macro” factors were beyond the scope of this survey.

Due to the constraints imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic, we were not able to draw a random sample that is representative of all eligible voters under 25 in the capital city Ulaanbaatar. Nor can we conduct face to face interviews with a large number of people. Instead, we used an online survey method with a self-selected sample. Hence, because of the non-random sampling technique we used, I urge caution when making inferences about the population parameters based on the results of this survey. With these caveats out of the way, here are four important takeaways from what we’ve learned about young voters.

One: Among those who voted in 2016 elections, most believe voting is their civic duty

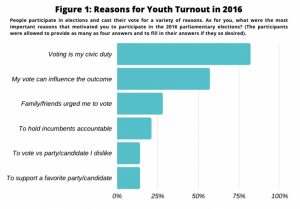

To gain an understanding of the factors that influence young voters to go to the polls, the survey asked the following question from the respondents who voted in 2016 elections: “People participate in elections and cast their vote for a variety of reasons. As for you, what were the most important reasons that motivated you to participate in the 2016 parliamentary elections?” The participants were allowed to provide as many as four answers and to fill in their answers if they so desired.

As Figure 1 shows, an overwhelming majority (82 percent) said they voted because voting is a civic duty. Fifty seven percent believe that their vote matters and that they thought they could influence its outcome by participating in the election. Also, 28 percent turned out to vote because their family or friends urged them to do so. Surprisingly, a much lower percentage of young voters, 21 percent, in our survey were retrospective voters, i.e., voters who evaluate the incumbent government’s performance in the past four years to decide how to vote. Likewise, those who turned out to vote because they liked/disliked a candidate/party were only 14 percent each. One could interpret these results to mean that partisan politics and ideological or policy debates do not strongly influence young voters’ decision to vote. Instead, most young voters vote in order to affirm societal norms or due to family pressures.

Finally, contrary to the widespread allegations of vote-buying during the 2016 elections, only three individuals said they voted for a candidate/party because they received gifts and money from a politician. Although this result might have underestimated the true extent of vote-buying due to a social desirability bias among the respondents, it is unlikely to have been a significant influence since the survey was anonymous.

Two: Young voters prioritize candidate-specific factors, especially level of education and career history

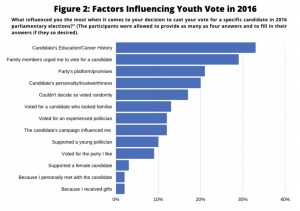

The survey asked: “what influenced you the most when it comes to your decision to cast your vote for a specific candidate in 2016 parliamentary elections?” Figure 2 suggests that the most crucial factor influencing the youth vote in 2016 was the candidates’ level of education and career history. One-third of the respondents who turned out in 2016 supported a candidate who was the most educated and had a distinguished career history in their mind. Three focus group interviews we conducted following this survey reinforced this result. On numerous occasions, focus group participants communicated their displeasure with some of the current MPs they described as “uneducated” and talking “nonsense.” When we asked why young voters should come out and vote in elections, they replied that because of their lackluster political participation, the older folks are electing “unqualified” and “uneducated” people who are running this country. They further asserted that if more young voters came out to vote, the government would be more competent and capable.

The survey reveals that family pressure was the second most crucial factor influencing how the youth voted in 2016. Twenty nine percent of those who participated in the elections voted for a candidate because their parents or other family members told them to do so. Given that young voters may lack experience with politics, it makes sense that their family members’ preferences may influence them.

The third most important factor was the parties’ electoral campaign platforms/promises. Specifically, parties’ campaign platforms/promises influenced about 21 percent of the young voters in our sample that participated in the 2016 elections. Next, 20 percent said they voted for a candidate they thought were most trustworthy, 17 percent said they voted for a random candidate because they were not sufficiently informed to make a substantive decision. About 13 percent voted for a politician because he/she looked more familiar. These findings are consistent with what we learned from our focus group interviews. Some participants expressed frustration with the lack of useful and objective information that could help them differentiate the candidates. Young voters said that information on the candidates’ level of education, age, career history, as well as short summaries of the most critical election platform/promises would help them make an informed decision on how and whom to vote for in the upcoming elections.

These results suggest that young voters are overwhelmingly non-partisan (only 14 percent have a favourite party) and hence were less inclined to prioritize the candidates’ partisan labels in the 2016 elections. Instead, young voters tended to examine the candidates directly without paying much attention to which party or coalition the candidates represented. Among the candidate-specific attributes, they cared most about the level of education, career history, and trustworthiness. The survey also asked about what the respondents will prioritize in the 2020 elections, and the results remain largely the same. Specifically, 56 percent of the respondents who are planning to vote in 2020 said they would look closely at the candidates’ career history, 52 percent said they would prioritize the candidate’s education, 39 percent the parties’ platforms/promises, and 37 percent candidates with a clean reputation. In contrast, only 7 percent said they would consider which party or coalition the candidates represent. These results suggest that in the context of this year’s multi-member majoritarian voting, a (young) voter might potentially vote for candidates from multiple different parties.

Three: Young voters care most about education reform

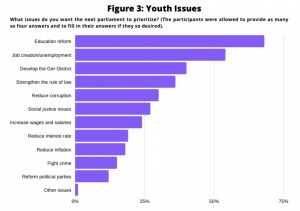

We asked young voters to rate the most pressing socio-political issues they want the next parliament to prioritize. Figure 3 shows that the number one issue they care about is education reform. In our focus group interviews, many participants reiterated this point as well. The participants were highly critical of the lack of a civic education curriculum that teaches about the core principles of democracy in Mongolia’s secondary schools. Others expressed their uneasiness about the growing inequality of access to higher education. These issues identified as most pressing by young voters are different from what the general population sees as the most important socio-political issues. According to the Sant Maral Foundation’s latest political barometer, education was ranked seventh pressing issue, with only 6.3 percent of the sample identifying it as an important concern. Thus, young voters have interests that are distinct from the general population.

Four: To have their unique interests reflected in public policy, they must vote

The principle of “one person, one vote” that underlies democratic elections entails that citizens, regardless of wealth, gender, and other factors, have an equal say in public policy. So, the equality of the franchise equalizes all citizens’ political influence. Nevertheless, this applies only to those who turn out to vote. If a significant segment of the public, such as youth, abstains from voting, then a distortion in democratic representation and accountability mechanisms occurs. According to the National Statistics Office of Mongolia, the turnout among voters under 25 in the last parliamentary elections was 51 percent, the lowest rate among all other age groups. Given that nearly half of young voters did not participate in the electoral process, it is safe to assume that policy-makers are neglecting the distinct interests of the youth and the issues they face.

When we asked from the respondents who abstained in 2016 why they did not vote, 36 percent said they were too busy to vote, 31 percent thought the candidates were not trustworthy, and 28 percent believed that it did not matter who was elected. Despite these reasons, to have their interests and concerns be reflected in public policy, Mongolia’s youth must vote in June. Part of the problem of youth abstention indeed lies with the political parties that refuse to compete based on programs and ideas. The electoral system is indeed inimical towards non-establishment candidates, thus discouraging young voters to participate. Furthermore, I share the sentiment that the candidates seldom are distinguishable from each other. Nor are they ever trustworthy.

Nevertheless, if young voters sit and wait for perfect candidates, they will wait for a long time. Even if it seems that candidates are all falling short of our expectations, is it not prudent to choose the ones who are less worse than the others? With the Covid-19 lockdown, universities, bars, clubs, and other establishments will remain closed. Hence, I expect that a much smaller number of young voters will say that they were too busy to vote after this year’s elections. And given the record number of younger and fresh candidates, I hope that young voters not make the same complaint that the candidates were indistinguishable.

About Boldsaikhan

Boldsaikhan Sambuu is a PhD candidate of political science at Waseda University in Tokyo Japan. He is an advisor to the Zorig Foundation as well as a host of the “54 Cups of Coffee” Podcast and “Bodcast” Podcast. Twitter: @BoldSambuu

Follow

Follow