By Paweł Szczap

[This is a second part to a post published on Apr 2 2021 focused on mass testing and risk areas.]

In order to combat the spread of COVID-19 in Ulaanbaatar, a two-week-long, citywide lockdown was introduced mid-February 2021. As the lockdown overlapped with the Mongolian Lunar New Year it was supposed to keep the disease at bay during a potentially very vulnerable period. Additionally, a mass testing program called Neg khaalga – Neg shinjilgee (One Door – One Test; below abbreviated as 1D1T) was implemented during the lockdown. Data gathered during the testing campaign served as a foundation for modeling the development of the local pandemic. 1D1T has been discussed in more detail in the first part of this text. After lifting the February lockdown, the number of new COVID-19 cases in Ulaanbaatar started increasing. Throughout March the emergency and municipal authorities were trying to avoid introducing a next citywide even despite the Health Ministry’s recommendations. Patterns which were made visible through 1D1T served as basis for enforcing a makeshift strategy of neighborhood lockdowns. This second part of the COVID-19-related March events’ summary deals mostly with restrictions on mobility in Ulaanbaatar throughout March 2021 and the relationship between the city’s urban tissue and the spread of COVID-19.

Emergency Measures

A notable increase in new cases is visible in the Mongolian Statistical Information Service’s data, starting March 5th i.e. ten days after the lockdown was lifted – just about enough time for people to reenter society, effectively transmit the disease and start showing symptoms. The strategy of the mass testing program was defective. This might have been due to various factors (but most likely their combination, including): using PCR test which are not best suited for mass testing, errors in testing procedures and communicating outcomes to citizens, lack of proper case investigation and contact tracing or too little time between tests and lifting of the lockdown just to name the most probable.

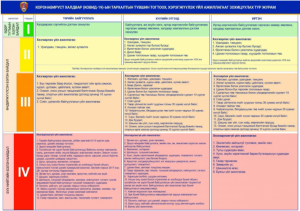

Orange-level state of emergency has been introduced for March 15th through March 29th and further extended to April 5th. On March 31st the State Emergency Commission seems to have upheld a version of this orange-level state of emergency until April 18th. In theory, this means a temporary halt for most venues and events related to leisure, other social activities and more. In practice many establishments continue functioning regardless. A detailed list of the restrictions sorted by emergency state can be found below:

In the case of many other cities, the phrase ‘partial lockdown’ implies partial limitations, such as those listed above. In the Ulaanbaatar context however, partial lockdown implies strict limitations but imposed only onto a specific neighbourhood.

The way in which the 1D1T campaign was designed as well as the way in which its outcomes are being utilized, all point to a narrative presenting the coronavirus as being transmitted nearly exclusively within residential areas. Also the strategy to combat the virus seems to be aligned with this residence-oriented narrative. This is not to say that measures related to public spaces and social life (e.g. as those listed above) are not being introduced. However, the household, seen as a container for the coronavirus infected, seems to be the main concern of the authorities. This leads to increased-risk areas being announced primarily on the khoroo (basic administrative unit of the capital) level, and so it is also the khoroo-level on which partial lockdowns are being enforced. Such an approach has both pros and cons but what is interesting in the local context are the parallels to be found with a strategy previously used to combat infectious disease (hoof-and-mouth disease in particular) in Mongolia. It is based around the idea of establishing smaller, marked and often policed quarantine zones in order to limit or fully prevent movement around and through areas of increased viral risk. This neighbourhood lockdown drill is already known not only in the countryside but also in the city.

Fig. 2 Part of the 5n buudal ger district locked off during an outbreak of hoof-and-mouth disease (HMD) in 2001. Photo by Gerelsaikhan

Fig. 3 An area in Ulaanbaatar’s Songinokhairkhan district quarantined due to confirmed cases of HMD, 2018

However, respiratory disease transmission occurs differently from that of HMD, and the approach to COVID-19-related partial lockdown measures should not be copied from the HMD drill in a 1:1 manner. It could also be seen on the recent example of Bayanzürkh district’s 26th khoroo, that if not sufficiently announced prior, closing off an area with a population of several thousand on the basis of several confirmed cases might spur further distrust towards the authorities’ actions.

Two Recent Partial Lockdowns

In recent days the case of Bayanzürkh district’s 26th khoroo’s temporary lockdown was covered by multiple media outlets. If one looks back at the announcements published since at least mid-February, this khoroo of nearly 24 000 inhabitants was repeatedly mentioned as a site of increased risk. Nevertheless, in took over a month for the area to become subject to a suddenly announced partial lockdown starting early morning March 17th, supposed to last until evening March 21st but lifted already in the morning of March 20th after confirming further cases and tracing their recent social contacts. Based on the number of cases, the area has been confirmed as one of the most COVID-ridden sites in Ulaanbaatar. It is likely that the lockdown was lifted earlier than originally announced partly due to social pressure by the khoroo’s inhabitants. On March 18th another partial lockdown was announced for the adjacent 15th khoroo of Khan-Uul district (khoroo population exceeding 13 000), including, among other residential complexes, also the Khurd/Rapid Kharsh residential district bordering the National Stadium. The two khoroos (Bayanzürkh district’s 26th khoroo and Khan-Uul district’s 15th khoroo) are part of Ulaanbaatar’s most densely populated southern residential belt, stretching along and south from, the Dund gol River (i.e. part of Selbe gol River). If any spatial pattern of COVID-19’s spread as based on residence areas is to be taken notice of, the two khoroos are at its core. They are part of a bow-shaped belt of outbreaks stretching south of the city’s main artery – Peace Avenue.

Outbreaks in High-Rise Residential Areas

The spread of the disease is accelerated by the composition of the urban tissue in the city’s built-up core, with its high concentration of interwoven high-rise residential districts, office and service facilities within close proximity to transport nodes.

A recent 3D visualization shared by the Municipal Emergency Commission allows for a better grasping of the overlap between high-rise residential areas and the confirmed COVID-19 outbreaks.

It can already be said with fair certainty that people living in the newer residential districts south of the city center form one of the core infected groups. This is because regardless of the circumstances of infections outside of the area of residence, the high-rise buildup and population density coupled with the proximity to service facilities makes transmission more likely. A higher concentration of people in shared spaces (especially elevators, service facilities like laundry rooms, gyms, small shops etc.) and other, similar instances of “sufficient” exposure to the disease create conditions favourable for effective viral transmission. Due to these newer residential districts’ self-contained internal structure (including on-spot shops and service points), they allow for decreased contact with the greater urban population, in theory making partial lockdowns more easily enforced. At the same time however, the same self-contained quality leads to increased contacts among smaller groups of the areas’ inhabitants and their widely understood “staff” (janitors, grocery shop and service point owners and staff, security etc.). When these workers eventually leave the areas and commute, often to the ger districts or go shopping to potentially crowded market places the disease might travel with them. Fortunately, as of the end of March 2021, ger district areas seemed to be least affected, which is mostly due to their low population density.

Outbreaks in the Ger Districts

Of Ulaanbaatar’s six central districts, Songinokhairkhan’s ger areas seem to be the most affected, with over 20 separate locations throughout multiple neighbourhoods. One might still be surprised that there hasn’t been more cases in the ger areas. The relatively low population density and sufficient air flow due to the areas’ elevation and land-use type, seem to obstruct the dynamic of the virus’ spread. To date, most of the outbreak locations in the ger districts, have been low in case numbers and rather dispersed throughout the areas, with multiple cases appearing several kilometers from the city centre. Public transport terminuses, often serving the role of local hubs with shops or market places, service points and public transport nodes all located in a relatively compact area also present a relatively high risk of virus transmission.

The often unobvious models of cohabitation among relatives might pose a challenge to adequate enforcement of thorough testing and contact tracing. Thus, the question remains regarding the reliability of the to-date testing efforts among the ger districts’ populations. Nevertheless, the main concerns in regard to the spread of the coronavirus in Ulaanbaatar’s ger districts are related to the difficult hygienic conditions, especially lack of running hot water. Along with the closing of many public baths, this poses increased risk especially to those of ger district’s inhabitants who work in the health sector. Another issue are the, often limited, possibilities of family members’ simultaneous self-isolation and quarantining in gers or unicameral houses. The cases of Khailaast and adjacent areas, (khoroos 13th, 14th, 16th, 18th Chingeltei district), Dambadarjaa (15th khoroo Sükhbaatar district) and Khaniin Material (6th khoroo Songinokhairkhan district) show us that it is not unlikely for the disease to gain numbers in the ger districts.

Selective Measures

When too much attention is directed towards closing off whole residential areas, the danger of overlooking other potential sites of increased transmission hazard rises. This is best exemplified by the outbreak in the National Academic Drama Theatre, where following a play attended by 900 people, 54 cases of COVID-19 infections have been confirmed among the institution’s staff.

Ulaanbaatar and emergency authorities are taking their best shots at three most important measures required for containing the spread of the epidemic: lockdowns, constant testing and accessible vaccination. When it comes to the enforcement of mass campaigns things seem forwarding: lockdowns (if enforced!) allow for testing, slow the virus down, make mass vaccination easier etc. However, where the most problems seem to arise is in between these grander measures. Judging from SEC’s decisions, another citywide lockdown does not presently seem to be viable option.

These problems take the shape of insufficient information campaigns resulting in a growing distrust for the authorities’ actions and complaints about a lack of transparency (mostly regarding financing and scientific backing for measures undertaken by the authorities). Irregularities of enforced procedures are being reported, regarding partial lockdowns, lack of proper medical support, faulty test results etc. Little attention is being payed to the impact of underaged vectors, transmissions and outbreaks in public and workplace circumstances such as those of the Bayanzürkh Hospital (mid-December 2020), the National Academic Drama Theatre (early March 2021) or State Emergency Commission’s Operational Headquarters (second half of March 2021) seem to be downplayed. Even though a strict lockdown seemed to be the most obvious path to take in mid-March, municipal and emergency authorities were having a hard time mediating between the possibility of new coronavirus outbreaks and the potential of social dissatisfaction outbursts. The latter ones arrive both from the better situated inhabitants of the southern residential belt as well as other groups including citizens without a steady income and others , to some of whom even a week-long lockdown constitutes a severe strike to their household budget. Thus, concerns with the state of the local economy also come into the picture. Unfortunately, also in this area the authorities are having issues with communicating their plans and concrete measures transparently enough.

At a press conference by the Health Ministry held March 22nd (daily Ulaanbaatar cases reported at 206), it has been explicitly stated that Ulaanbaatar as a whole should be treated as one large outbreak site. On the same day, the postponing of a potential lockdown until April 5th has been announced by SEC. The Commission’s decision came just days after its previous announcement that Ulaanbaatar will be entering into a lockdown if new daily cases exceed 200. In the last days of March the number of new daily cases kept increasing. On March 31st SEC dismissed the possibility of introducing a citywide lockdown before April 18th. This decisions might seem justifiable when seen in the context of earlier estimates, according to which, by May 1st around one million of Ulaanbaatar’s citizens are supposed to have already developed COVID-19 immunity after completing their vaccination procedures. The question remains whether, in the present epidemiological situation, the authorities will be able to follow up with the vaccination program as previously planned.

Further Partial Lockdowns

Due to the dissatisfaction voiced over the above-discussed lockdowns of Bayanzürkh district’s 26th khoroo and Khan-Uul district’s 15th khoroo, these partial lockdowns are now been euphemistically dubbed “broadened survey measures” and presented as creating conditions necessary for thoroughly testing and tracing social contacts of a given target group, rather than as restrictions enforcing limitations upon people’s mobility. One of the next locations where “broadened survey measures” are most probable to be carried out is Bayangol district’s 12th khoroo, containing the so-called Bichil khoroolol. Contrary to the two previous locations filled mostly with newer buildings, the khoroo in which Bichil is located consists largely of late socialist-period prefabricated residential buildings. Another location whose lockdown might become necessary is the 3rd khoroo of Khan-Uul district. With its multiple plant and manufacture facilities, located in a small area with limited public transport access routes, it creates very convenient conditions for the virus to spread and might soon become a textbook example of a workplace viral transmission node. Since it is not a residential area, multiple financially-backed entities might become engaged in the process of negotiating the khoroo’s potential lockdown.

The Wolves Come with the Rain

Due to the population numbers and density as well as the Ulaanbaatar’s role as Mongolia’s main transport hub, the epidemiological situation within the city is crucial for the containing the spread of the pandemic in the country. Of the several national and municipal level authorities cooperating to tackle the spread of the COVID-19 epidemic in Ulaanbaatar (the Health Ministry, the National Emergency Management Agency, the State Emergency Commission , the Mayor’s Office, the Municipal Emergency Commission), the State Emergency Commission is the main “political” face the whole process.

A popular proverbial line “chono boroonoor” (the wolf [utilizes] the rain) recently updated to the current circumstances states “chono boroonoor, UOK koronoor”(he wolf [utilizes] the rain, SEC [utilizes] corona), expressing the popular dissatisfaction with the recent actions of the authorities and concerns with the lack of accountability. Even despite the non-stop work being put in by SEC, its previously valid line of argumentation, based on the fact of securing Mongolia’s relative safety throughout most of 2020, now seems to be loosing its previous leverage, one useful or even necessary to legitimize actions lacking wider public support. The already decreasing support for SEC’s decisions is likely to be further affected in April. This is not only due to the potential of the pandemic’s growth but also due to the fact that deaths resulting from the post-lockdown, March infections are bound to start coming up in April statistics, delivering delayed information about last month’s actual death toll.

An extended version of both parts of this “Ulaanbaatar: COVID-19 as of March-21” summary/commentary along with other resources can be found at: https://ubstudies.wordpress.com/covid-19-in-ulaanbaatar/

About Paweł Szczap

Paweł Szczap is a Mongolist, Mongolian language translator and PhD candidate at the University of Warsaw. He mostly works with the Mongolian built environment and is currently researching Ulaanbaatar city maps and place names. He has spent over four years living in Mongolia and has on numerous occasions cooperated with the Ulaanbaatar City Museum. Previous works include research on Mongolian nationalism and the cultural impact of mining among others. He is currently developing two online projects: Ulaanbaatar Studies and Mongol hip-hop.

Follow

Follow