Introduction

Throughout history, many civilizations have posted public edicts in the form of inscriptions on stone columns and buildings. The ancient Greeks used wooden panels to mount official announcements, while the Romans employed a system of outdoor publicity in the form of whitewashed walls, called albums, painted with official messages using red or black paint (Weill, 1985). Any tampering of these announcements was often met with corporal punishment.

With the fall of the Roman Empire and Europe’s descent into illiteracy, official proclamations became the purview of the town crier (Weill, 1985). Medieval villages were filled with the cries of merchants and criers all vying for the attention of the town folk. It was not until the invention of the printing press around 1450 that we begin to see handbills and placards advertising the wares of publishers. These early posters were largely text-based proclamations that sometimes included images created through intaglio or woodcut printing. Since engraving was an expensive process, printers often printed posters with stock images that they could then fit the text into (Weill, 1985). Many were used to attract the religious faithful or recruit soldiers (Weill, 1985). Again, limits are placed on who can post or tamper with these public announcements.

By the 18th century, placards are numerous and, in Paris, plastering posters on every available wall eventually led to their strict regulation. Forty official bill posters were appointed to ensure that all posters bore the mark of approval from the chief of police before they could be posted (Weill, 1985). Armed with an official badge, a ladder, an apron, a glue-pot and a brush, the bill posters rarely read what they posted. And yet, despite this regulation, posting still thrived throughout Paris. It is at this point with the invention of lithography that the modern poster is born.

The Process of Lithography

The process of lithography was invented in 1796 by Alois Senefelder, a German playwright, who was looking for an inexpensive way to publish his works (Weill, 1985). Through discovery and experimentation, Senefelder learned that he could etch an image into a limestone tablet for printing without the need for carving. While the process of lithography involves many steps (as can be seen in the video below), it is in principle, quite simple. At its heart, lithography is based upon the principle that water and grease repel each other.

To begin, the artist takes a smooth limestone tablet and, using an acid-resistant greasy ink, draws an image upon the limestone. The stone is then washed with a mild acid that will etch the parts of the stone not covered by grease thus fixing the image into the stone. Next, the stone is made damp and ink applied. As the etched part of the stone retains water, this repels the ink, leaving only the greased parts (the image to be printed) covered with ink. The image is then printed when paper is pressed onto the inked stone (Weill, 1985).

This process greatly increased the speed and reduced the cost of the printing process for images since the artist no longer needed to carve the image as with intaglio woodcuts. Instead, the artist was able to work with pencils and brushes, a medium that allows for finer dexterity and control over the intricacy of the image.

Further developments by Godefroy Engelmann led to the patenting of the process of chromolithography in 1837 (Weill, 1985). In chromolithography, multiple stones were used to apply colours to the printed image. Since a separate stone was used for each colour, this meant that each stone had to be etched with the part of the image that was intended to hold a particular colour. To complete a single image, each stone (and colour) had to be printed onto a single sheet of paper with the paper being allowed to dry between printings. It was important in this process that the image on the stone and the paper were lined up exactly to ensure a precise print.

The Modern Poster is Born

A poster by Jules Cherét.

Although first introduced in 1869 by Jules Chéret, it would take another decade before the modern colour poster became widespread (Gliem, 2008). Chéret’s posters, with their use of pastel colours, light and airy compositions, and often featuring a coquettish girl in an attempt to capture an air of fun and frivolity (Gliem, 2008), captured the attention of the public and other artists alike and inspired many disciples (Weill, 1985).

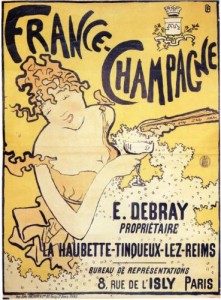

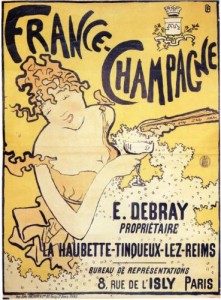

France-Champagne by Pierre Bonnard (1891).

By the mid-1880’s, with the repeal of French laws that prevented posting in public spaces, posting became big business in Paris and many walls commanded a hefty annual rental fee (Weill, 1985). Chéret’s style, inspired by 18th century Rococo, would eventually give way to the bold and original designs first inspired by Pierre Bonnard’s poster for France-Champagne with its use of flat shapes and hand lettering that was integrated into the overall design (Gliem, 2008). Prior to Bonnard’s poster, lettering was often considered to be extraneous to the poster’s design and many artists, including Chéret, employed a specialist to do the lettering (Gliem, 2008). The last part of the 19th century is often referred to as the golden age of posters in france and it is hard not to see why with prolific and accomplished artists such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Alphonse Mucha leading the way.

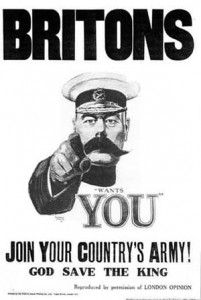

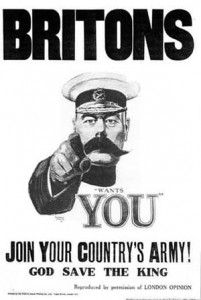

Alfred Leete’s “Your Country Needs You” poster.

The poster was to reach its heyday during the First World War as a propaganda tool to build support for the war effort. Artists used vivid imagery filled with patriotic symbols designed to provoke a personal and emotional response. Posters filled with images of Uncle Sam, Lady Liberty, Britannia, flying flags, crosses, bibles, and the evil Hun were used to raise a call to action and to sell war bonds. The most famous poster of this era was James Montgomery Flagg’s Uncle Sam poster. Based on Alfred Leete’s “Your Country Needs You” poster featuring Lord Kitchener (a successful recruitment poster in its own right), Flagg’s creation exceeded 5 million copies in print (Allen, 1994).

The Impact Upon Literacy

Prior to the invention of lithography and the modern poster, the illiterate were virtually shut out from understanding the largely text-based placards. It is small wonder that the town-criers of the Middle Ages were so successful. When an individual cannot read the latest pronouncement from the King, they must rely on word of mouth to understand the message. With lithographic printing and image-based posters, it was suddenly possible for the illiterate to gain entry to the world of posters. The images conveyed meaning far faster than text and captured the viewer’s attention, be they literate or not. Posters rich with imagery and symbolism carry meaning and feeling and can connect with us on an individual or group level. Symbols are the concrete embodiment of the ideas, feelings, values, and beliefs of a society at that time and the successful poster maker is able to exploit the imagery to motivate his spectator to take a particular action or hold a certain belief (Allen, 1994). Whether it was used to sell soap flakes or urge men to enlist in the war, the poster, replete with imagery and symbolism, became a powerful tool for mass communication and propaganda.

The impact of the poster on literacy can be seen in its simple ability to combine text and imagery into a cohesive whole with the goal to communicate a particular message. Posters were designed for public display, to attract attention, and to communicate a thought or idea. The strength of a poster is measured in terms of its effectiveness at capturing the public’s attention and spreading its message. That message should not be a mystery, but should instead convey its meaning “swiftly and convincingly” (Allen, 1994, para. 4). Successful posters use the symbols and idioms of the day to resonate with the public and leave them in a favourable frame of mind. The poster must attract curiosity, capture the imagination, and embolden its audience to act (Allen, 1994). It is more than just an art gallery in the street.

Posters in Education

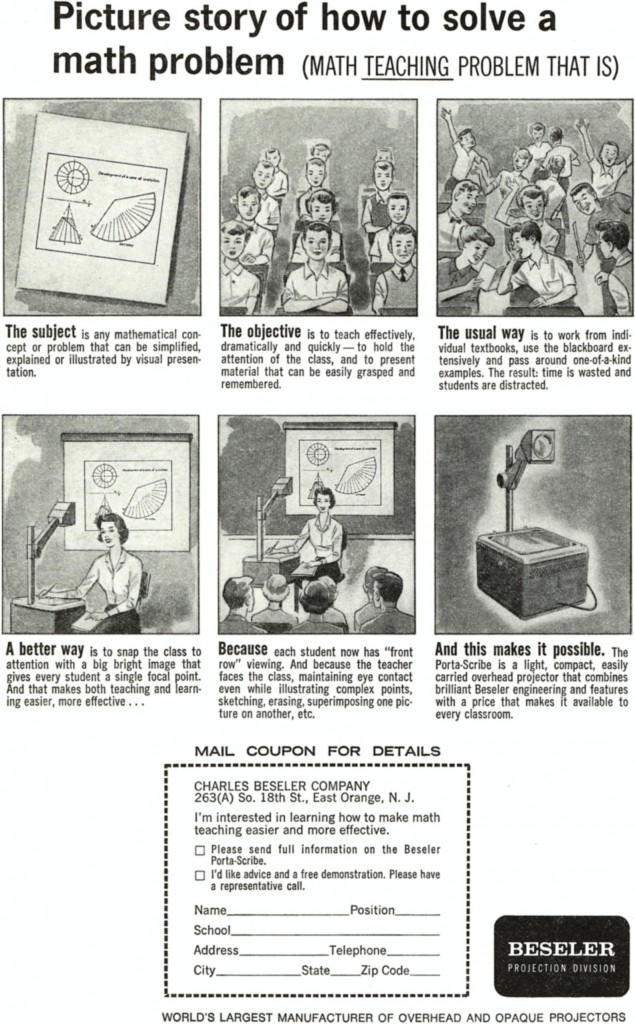

The poster has found its home in the classroom. Its blend of short, memorable phrases and rich imagery are the perfect vehicle to capture the attention of the newly-literate student. Posters in the classroom are often used to teach new concepts, reinforce basic facts, highlight the important, enforce the rules, and direct students to the bathroom in the nick of time. A classroom, and therefore its teacher, is often judged by the quality of posters on the wall or lack of thereof. While the fire marshal may admonish the prolific use of flammable paper posters on classroom walls, students and parents come to expect their presence. Posters help to create a warm and inviting classroom, whereas a classroom devoid of posters is seen as cold and boring.

The power of the educational poster lies in its ability to combine imagery and text so as to make the material to be learned easier to retain and recall (Wharrad, Allcock, & Meal, 1995). However, posters are not just tools for teaching. They are also used to capture learning and for assessment. A long time favourite activity of students, the poster is often made an assignment in itself. Whether it is used as part of a novel study or a science fair, students love the opportunity for creativity and self-expression in their design of a poster representing what they have learned. Such a personalized assessment is far less stressful for students (Wharrad, Allcock, & Meal, 1995).

As early propagandists discovered, the layout and structure of a poster can have a profound impact upon successfully communicating its message. In the classroom with young learners, this is of critical importance. The size and style of the typography, the use of colour and white space to balance elements, and the choice of imagery all play a role in whether young students will find the poster memorable and useful or just plain confusing (Christenbery & Latham, 2012).

However, the overuse of posters can be a detriment to the young learner. With most free wall space covered in posters and artwork, the student can easily become saturated with information and unable to find and focus on a particular poster when most needed. Judicious use of space and frequent poster rotation are two tactics often used by teachers to keep things fresh in the classroom. Since the poster is a relatively easy and inexpensive tool for teaching, it is not likely to disappear from the classroom any time soon.

References

Allen, R. F. (1994). Posters as historical documents. Social Studies, 85(2), 52.

Artsmia. (2008, June 24). Printmaking processes: Lithography. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JHw5_1Hopsc

Bonnard, P. (1891). France-champagne. [Poster]. Retrieved from http://www.wikipaintings.org/en/pierre-bonnard/poster-advertising-france-champagne-1891

Cherét, J. (n.d.). Jardin de paris. [Poster]. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cheret,_Jules_-_Jardin_de_Paric_%28pl_65%29.jpg

Christenbery, T. L. & Latham, T. G. (2012). Creating effective scholarly posters: A guide for DNP students. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practioners, 25, 16-23. Doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2012.00790.x

Gliem, D. E. (2008). Japonisme and bonnard’s invention of the modern poster. Japan Studies Association Journal, 6, 17-38. Retrieved from http://www.academia.edu/2070503/Japonisme_and_Bonnards_Invention_of_the_Modern_Poster

Leete, A. (1914). Kitchener world war I recruitment poster. [Poster]. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Kitchener-Britons.jpg

Nnmiles1. (2013, June 21). Classroom posters! [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0a-eO3qdBIc

Weill, (1985). The poster: A worldwide survey and history. Boston, MA: G. K. Hall & Co.

Wharrad, H. J., Allcock, N. & Meal, A. G. (1995). The use of posters in the teaching of biological sciences on an undergraduate nursing course. Nurse Education Today, 15(5), 370-374.

The Printing Press and Impacts

The following is a video on the impact of Johannes Gutenberg’s Printing Press.

It outlines a brief description of printing and movable type, and then discusses the impact of the press in three areas: the expansion of literacy, the consistency of language, and the change to education. I experimented with my own version of animation at the beginning and although not I find it rudimentary looking, I know I will improve each type. In addition, I also now recognize that youtube takes a really, really long time for upload. This video? About 27 hours, infuriating me, but also provided a great learning lesson. Finish early so you can upload early.

Thanks and enjoy the show.