By Camille Barras

A demographic analysis of candidates to the 2020 Ikh Khural elections has unveiled a low share of women among candidates – just over the 20% legal quota for the two main parties and about 14% only among independents – with the notable exception of the Demos Party. The percentage of female candidates therewith appears to be even smaller than for the previous election.

By contrast, we also know that women vote at a considerably higher rate than men in Mongolia, and this across the country. How to explain this chasm between female political participation and representation? Survey data can shed light on how Mongolia compares to other countries and generate some insights into this question.

High female political engagement beyond voting…

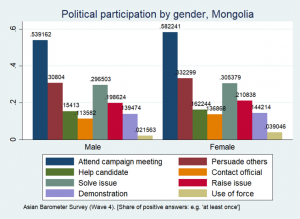

First of all, not only do Mongolian women turn out at the polls more than men, they are also systematically more active with regards to other forms of political participation such as attending campaign meetings, as Graph 1 shows. This seems quite unique, if looking at the same data (Asian Barometer Survey Wave 4, 2014) for other Asian countries (men outdo women for most of these indicators throughout the region), but also when considering wider international evidence of a remaining “traditional” gender gap for political actions others than voting.

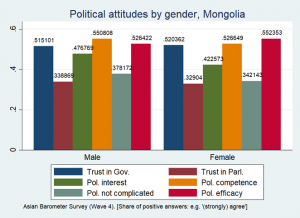

The picture slightly changes for political information and discussion. While 53.3% Mongolian men follow news several times a week or more and 76.8% discuss politics at least occasionally, only 47.5% and 72.9%, respectively, of women do so (Asian Barometer Survey Wave 4). For these indicators, Mongolia does no longer have the lead in gender equality in the Asian region. (As an aside, similar comparisons could be done with countries from the post-communist area using the Life in Transition Survey).Similarly, compared to men, women have lower levels of political interest, political efficacy (sense that one can have an influence on what the government does), and further political attitudes, but higher trust (Graph 2). This is in line with findings from much of the world. Gender differences nevertheless appear to be relatively small (the largest is 5 percentage points for political interest) and, by and large, minimal compared to most other Asian countries.

… but prevailing gender bias with regard to women in politics

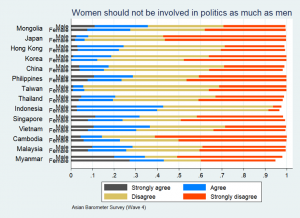

However, figures about gender norms stand in sharp contrast with Mongolia’s quite exceptional rate of political participation (at large) among women and relatively small gender differences in political attitudes. More than a third (36%) of men agree or strongly agree that “women should not be involved in politics as much as men” – while 28% of women do so. These values are among the highest in the Asian region (see Graph 3). Interestingly, the discrepancy between men and women also seems larger than elsewhere, hinting at a potential polarization between genders around this issue.

In other words, despite women being more politically active in practice, politics is still seen by many as the (exclusive) realm of men. This gap between behaviours and norms is common in many countries but appears as particularly glaring in Mongolia’s case.There is little doubt that this prevailing gender bias regarding women’s involvement in politics is one of the major barriers (yet not the only one) underlying the low, and decreasing, female political representation in Mongolia. It is likely to affect both the nomination and election of women, that is, to play a role both within political parties and in voters’ minds at the polls. In 2016, 26% of candidates from parties and 19% independents were women according to this report. The share of women dropped further at the election stage. Women make up 17% of representatives in the current Ikh Khural – thereby placing Mongolia 122th out of 189 countries on the IPU ranking – and between 15.7% (aimags) and 28.2% (districts) in subnational khurals. With women candidates being even more scarce on the 2020 lists, will the share of elected women reach 2016’s level?

Can participation translate into representation?

Yet we can wonder whether women’s high political engagement could have any effect on women’s political representation.

Looking at the aggregate level, UB constituencies, where the reverse gender gap in voter turnout was highest in 2016, represent 36.8% of parliamentary seats but 61.5% of women MPs (8 out of 13 female MPs were elected from UB districts). There is also a positive association between the gender turnout gap (in national elections) and the share of women elected into Citizens’ Representative Khurals at the subnational level in 2016.

Of course, this is an extrapolation and should be interpreted with caution. The relationship may also be spurious: in some electoral districts, women may vote more and stand higher chances to be elected for some other reason; or perhaps political parties field more women candidates where female turnout is higher? It would be interesting to compare, in the future, female turnout and electoral success taking into account the number of women candidates for the 2020 elections.

At any rate the singularly high political participation of women in Mongolia might represent an interesting potential to tap into for female candidates. From previous studies elsewhere it seems that women may well prefer voting for women (and men for men), but that this hinges on a number of contextual factors, notably on the electoral system and gender balance of candidates.

It could also depend on the extent to which female candidates play the “women card” – in other words, whether they run their campaign explicitly promoting themselves as representing women, advocating for women-specific issues and / or calling for women’s support. Lastly, the generational shift among voters, with the arrival of high numbers of (male and female) young voters with potentially different mindsets and gender norms, is a further key element to consider in this regard – even more so if youth’s voter turnout were to increase.

About Camille Barras

Camille is a PhD candidate in Politics and International Studies at the University of Cambridge. Her research focuses on subnational governance and political engagement. Before that, she worked in International Development, and lived in Mongolia for her last posting.

Follow

Follow