By Bulgan Batdorj and Anand Jangar

Today, our guest is Ms. Selenge Sambuu, executive director of the “Association of Parents with Differently-abled Children” (APDC). She started as a board member of the association and transitioned to her current position as executive director. The association has existed for over 20 years and Selenge has been working there for 11 consecutive years managing the day-to-day operation. She has a background in engineering but changed her profession to take care of her child with disability.

About the APDC

Selenge shared with us the origin story of the association. In the late 1990s, the British Save the Children organization arranged an orientation for parents with children with disabilities in Mongolia. The parents got together through the orientation activities and realized the importance of forming a support group for the parents of children with disabilities and for raising public awareness. Then those parents created the APDC in 2000, to become the voice of disabled children. The association now has 20 branches across Mongolia, four in Ulaanbaatar and 16 in the countryside. The association aims to help children with disabilities and their parents exercise their rights as human beings. Selenge said that “children must be diagnosed with a disability as soon as it is noticed” and get the necessary support from the government. Countries like Japan and the USA have these government support systems and trained professionals. They diagnose disability at an early stage and support the parents and the children in overcoming the challenges.

There are 11,600 children with disabilities in Mongolian. These children must be allowed to learn at local daycares and schools with other children of the same age. Selenge believes that this process will help educate children with disabilities, create public awareness, and encourage a society respectful of children with disabilities. The association focuses on all types of disabilities and supports the parents of children with disabilities. In the last few years, the association focused on providing parents with legal benefits and knowledge to help their children create a prosperous future for themselves.

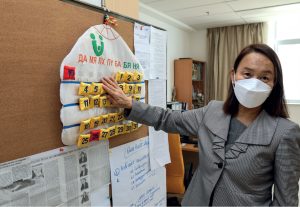

Photo: Ms. Selenge in the office of the Association of Parents with Differently-abled Children (with the permission of Selenge)

The Main Obstacle to Achieve Fundamental Human Rights

Our guest illustrated the many problems in our society that make life challenging for children with disabilities in Mongolia. Of the 11,600 children with disabilities in Mongolia, around 4,000 (34%) are illiterate and do not get any support, regardless of whether the child lives in the capital or in a remote community in the countryside. These children have problems commuting, participating in events, accessing education, and receiving medical services. Selenge stresses that although the Mongolian Constitution and the Mongolian ‘Law on Education’ state that “every” Mongolian citizen has a right to free basic education, the wording of “every” citizen needs to include “children with disabilities” proactively. “Although children with disabilities may be limited in their abilities compared to ordinary children, this does not mean that these children should be excluded”, she continues. They must be allowed to develop their skills, their abilities, and to push their limits to achieve their destiny.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities states that citizens with disabilities should be enabled to develop themselves to their full potential. The Ministry of Education and Science of Mongolia adopted the 155th Order in 2018 which states that the Individual Training Program aims to develop children with disabilities following the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Although it is an exciting time, in theory, most of those children with disabilities in Mongolia cannot fully enjoy their right to learn, develop themselves in schools, and participate in anything since curriculums are not designed to serve and meet the needs of those disabled children, and teachers are not trained to work with disabled children. Most of the time, these children are denied admission to schools simply because of their disability. In other words, although there is an order from the Ministry, the system does not exist. If there was a system and support in place, all these 4,000 children with disabilities would enjoy their right to learn.

Selenge shares that the APDC is discussing and continuously submitting proposals to the law. Amendments to the ‘Law on Education’ and the ‘Law on Primary and Secondary Educations’ will add a supporting program service for students with disabilities in schools. This service will help students with disabilities commute to school, will assist in hiring professional teachers specifically trained to teach students with disabilities as well as teaching assistants sign language interpreters, psychological counsellors, and therapists. Furthermore, it will introduce after-school programs, and much more. Selenge and the APDC office hope to collaborate with many like-minded organizations such as NGOs to receive aid from private sectors, and work with welfare services to create a system to support the children with disabilities.

What Are the Biggest Problems for the Parents of Children with Disabilities?

There are many problems that the parents face. The government does not provide enough advice and information regarding disability. Due to lack of information, parents end up trying to treat their children’s disability while forgetting to educate and develop their children, which results in the loss of the precious ‘Golden Age’ of learning, a vital time in the early brain development of these children.

When parents first see their newborn child being disabled, they often experience a feeling of dejection and despair, and the government does not have any emotional support services. Parents usually have two ways of responding to their children’s disability.. For one, they try to help their children too much, which results in the kids becoming overly dependent which discourages these children from forming a sense of independence. The second way is that the parents try to treat untreatable disabilities, such as amputated limbs, because the family members of the children with disabilities cannot accept the disability. As the parents lose valuable time trying to ‘treat’ these disabilities, the children grow into uneducated and illiterate adults who have no future for themselves.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights has a different perspective. Aside from a person’s disability, societies often worsen the living conditions of the these people by adding various barriers. For example, a grocery store can incapacitate a person even more by not adding ramps for the handicapped in wheelchairs.

Mongolian Society’s Attitude towards Citizens with Disabilities

Although the citizens with disabilities are the largest minority group, and will always be a part of the society, they are a marginalized community. In the absence of social awareness and advocacy groups, the APDC formed as a grassroots movement to enlighten the Mongolian society and give the voiceless a voice. She said that numerous protests are organized in Mongolia by various organizations to help the people with disabilities. As for the international context, the first revolution for the disabled took place in the USA in 1970. The citizen with disabilities protested by crawling up the stairs of the US Capitol to let the congressmen and congresswomen know that they forgot about helping the people with disabilities. As a result, the Rehabilitation Act 504 was enacted in the US to ban discrimination of the people with disablities. In Mongolia, the Mongolian Ministry of Social Welfare initiated a law that showed support for the rights of persons with disabilities in 2016. Also, the Mongolian government committed to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2009. The APDC tries to ensure the government’s commitment to fulfill the terms of the convention.

Reflections

Mongolia still has a long way to go to match the global advancements in inclusion and diversity efforts, and this includes infrastructures for the people with disabilities. However, people like Selenge, advocating and championing Mongolia towards a path that is accessible, fair and equal, are truly worth celebrating. Listening to the interview reminded us that we have to lend our voices to organizations that are led by the guests of the Untold Podcast until everyone exercises their rights as global citizens, and equal beings.

The Untold podcast and blog post are made available by the generous support of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation in Mongolia. We also want to thank our editor Riya Tikku.

Follow

Follow