By Degi Bolormunkh

Our guest today is Ms. Gerel, the President of the Mongolian National Federation of the Blind (MNFB). Ms. Gerel gives us an introduction to some of the work the MNFB does, offers her personal experience and advice, and addresses some of the systemic challenges faced by visually impaired people and people with other disabilities.

Mongolian National Federation of the Blind (MNFB)

The MNFB, established in 1978, is one of Mongolia’s long-standing organizations promoting disability rights. The MNFB currently has 86 employees and focuses on key areas such as education, employment, vocational training, social support, and other issues related to protecting visually impaired people’s interests in Mongolia. The MNFB undertakes various activities such as publishing audiobooks and books in Braille and runs kindergarten and adult education centers. They have training centers for massage therapy, barista, and felt craft that provide employment support for visually impaired people. The organization’s main focus is on the specific challenges visually impaired people face and the advocacy for their improvements in society. One of the main challenges is the limited access to information, and hence, the MNFB operates a FM radio station broadcasting news and featuring topics of literature. They have around 9000 members all around the country, including branches in all the 21 provinces. A core focus of the organization lies on political influence and advocacy for the legal rights of visually impaired people. The MNFB is particularly concerned with issues related to the prevention of violation of rights, intervention, and action when rights are violated, and influencing policy and decision-making that can protect and serve the needs of the people they represent. There have been some financial constraints, but the training centers, donations, partnerships, donor support, and government grants have been helpful in maintaining a continuous operation. Major pressures and problems imposed by external issues, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, can be substantially disruptive to financially constrained organizations. This is an important consideration for policy and decision-makers when supporting socially conscious organizations that advocate for social inclusion and equality. The MNFB’s long-term vision is to establish international best practices and standards concerning inclusion and accessibility in order to improve the lives and social environments for everyone in Mongolia. For instance, they are looking to establish a vocational rehabilitation center that helps people with disability to overcome relevant physical, social, and financial barriers, and assist them with socialization and employment. Notably, the center would also help people with disabilities to learn about better coping mechanisms to manage and overcome their challenges on a personal level. Ms. Gerel advises that the key to running a successful NGO is to have a clear purpose, to foster an unwavering drive to help, and to find supportive partners.

Ms. Gerel’s Personal Experience

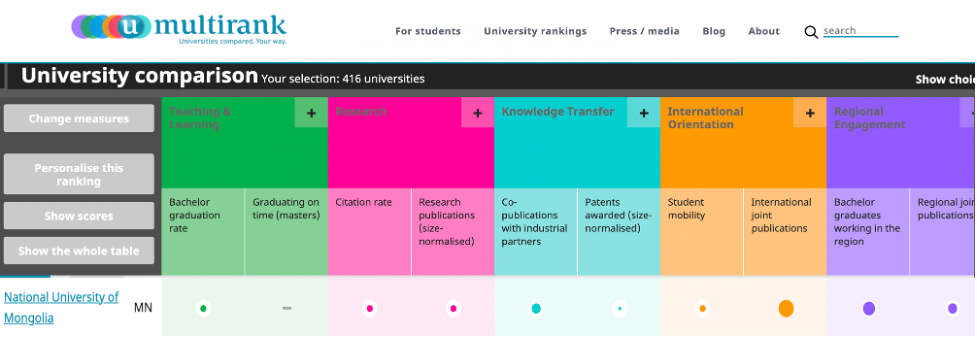

Ms. Gerel started her career at the MNFB in 2006 in the position of Deputy Director. The MNFB chooses their representatives and leaders every four years at a General Assembly and has 15 board members. She was first elected as the President of the MNFB in 2013 and, in 2017 she was re-elected. Ms. Gerel emphasized the need to do more in order to create a more inclusive and equitable society. She became visually impaired in her 3rd year at the National University of Mongolia where she was a law student. At first, it was hard for her to cope with the loss of her vision and to face its many accompanying issues. With the support of her friends and family, she was able to finish her studies. However, the experience completely changed the way she thought about life, time, and the value of education. She realized that language is very important, especially for visually impaired people, and felt a strong sense of purpose in her pursuit of education. She recalls how she started learning English on the radio using a voice recorder to record and review the English lessons that aired. When she got her first computer in 2007, she was able to learn to read and write in English with a strong resolve. In 2010, she had the opportunity to go to India for ten months and when she came back, she took the IELTS test. Learning English enabled her to go on a Fulbright Scholarship in the United States where she completed her master’s degree in International Human Rights. She shares her experience about the time when she lost her sight at university and then going back to school after taking time out. She recalls that there was discomfort and doubts at the beginning with her new classmates and teachers, but as she spent more time with her class community, they became better informed about her challenges and learned to support her without discrimination. In her experience, she found that in social settings people were less informed and uneducated about the needs, challenges, and abilities of people with disability, and thus, increased socialization and interaction is important. Simply having a conversation about people with disabilities and understanding their experience can increase public awareness about the need and demand to build an inclusive and more compassionate society.

Major Challenges People with Disability Face

Some major challenges she and her team share are concerning the inadequacies of the current state of affairs, including full enjoyment of their human rights, equitable social inclusion, and quality of for people with disabilities. For instance, out of 1200 children aged 0-17 who are visually impaired only around 200 children are in school exercising their right to education. Basic rights such as the right to education and the right to employment are difficult rights and the legal and social environments are not accommodating to these challenges. Many people want to send their children to school, but a lot of times they just do not have the knowledge and training to accommodate children with disabilities. There are already many specialised international standards and methodologies that specifically accommodates the educational needs and challenges of visually impaired children which can be adapted and incorporated into the current education system to improve equitable accessibility. Despite being an NGO, the MNFB takes on a lot of public issues that should be tackled by governmental and legislative means. Ms. Gerel and her team identify that the underlying cause of these issues and challenges are due to ignorance and the lack of awareness among our population about the specific challenges faced by people with disability. Ms. Gerel is optimistic that Mongolians can easily adapt and improve inclusivity once there is more awareness and better understanding. However, Ms. Gerel condemns the general attitude of over-sheltering which many Mongolian families have towards family members with disability. This seemingly innocent and well-intentioned attitude can discourage people with disabilities to be active in social spaces and be involved outside their household, which then can have negative effects on the public awareness of disability issues. Many of the people who come to the training centers at the MNFB are people who rarely step out of their homes. The different resources and support provided by the organization encourages them to be more actively involved in their community and society at large.

Public Awareness and Informed Governance

Continuous social involvement, public education efforts, and advocacy are key to generating public awareness and improving the understanding of specific challenges, needs, and solutions which then can spur changes in attitude and action at all levels of society. Ms. Gerel encourages other people with visual impairment to be more involved in common spaces, public discussions, and social life in general. Ms. Gerel reminded the listeners that without deeper understanding about the specific challenges, needs, and abilities, it is difficult to bring about social and political changes. She also expressed the importance of systemic change and legal frameworks that can directly address key barriers that hinder people with disabilities from enjoying equal rights in society. Even if there are legislatures that are in place, decision-makers need to be more informed about the specific challenges for people with disabilities and focus more on execution and enforcement. Furthermore, the society needs to ensure the removal of legal, physical, and practical barriers that people with disability have today. Ms. Gerel compared the visibility of people with disability in social spheres in Mongolia with that of Australia, where there is more public awareness and social engagement surrounding the issues faced by people with disability, as well as wider availability of support and resources for people with disability.

Key Insights

Ms. Gerel highlighted the importance of distinguishing and identifying the specific challenges faced by people with different types of disabilities in order to appropriately address them in social and political domains. For instance, visually impaired people face challenges unique to their disability and therefore have different needs than people with a hearing difficulty. She touches on the diversity of special challenges, the needs that different types of disability groups experience, and the necessity to have specialized organizations that can address and advocate for those unique differences. In order to provide an equitable and inclusive environment in society, we first need to recognize and understand the different kinds of challenges different disability groups face. In terms of policy and regulations, decision-makers should not only use umbrella terms and definitions but also be considerate of the various challenges and needs different groups have. Public awareness efforts, increasing social visibility, and self-advocacy are important ways that can improve social understanding and government responsiveness to the needs and challenges of people with disability.

Author: Degi Bolormunkh is a young professional with a multi-disciplinary education and a diverse background. She is a recent graduate from the Master of Management program at the UBC Sauder School of Business. She completed her B.A. in Combined major of Political Science and Philosophy with a minor in International Relations from the University of British Columbia. She has lived in multiple countries and has developed a keen interest in issues surrounding DEI, social and political inequality, and good governance.

The Untold podcast and blog post are made available by the generous support of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation in Mongolia. We also want to thank our editor Riya Tikku.

Follow

Follow