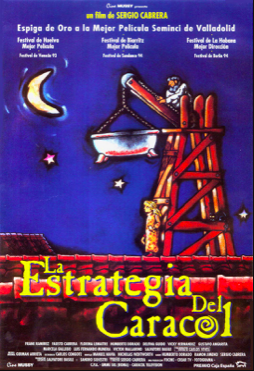

La estrategia del caracol no es sólo una historia sobre el despojo. O más bien, es una historia sobre la intervención y la transformación del despojo en otra forma de desplazamiento o mudanza. La película comienza cuando un grupo de periodistas llegan a una calle atiborrada de cosas. El reportero del grupo pregunta a un hombre viejo qué es lo que pasa, y éste, a punto de responder de forma agresiva, es interrumpido por otro personaje. Éste se presenta como miembro de la ya desalojada casa de “la Pajarera.” Y en palabras de este nuevo personaje, “el paisa,” lo que el reportero está presenciando es la “injusticia de la justicia.” En este sentido, la historia que vemos ya iniciada es la ya sabida historia de la acumulación originaria, aquella del robo y el despojo, aquella escrita en letras de sangre en los anales de la historia. De ahí, el paisa comienza a narrar la historia de un despojo previo, de “la Pajarera” y de una casa vecina, al reportero y su equipo. Esta primera escena ya resume un mecanismo que se repite en la película. Este mecanismo consiste en un desplazamiento del afecto por una narración o creación artificial (la reacción del hombre viejo por la narración del paisa), y también la de la intervención de un tiempo diferido. Es decir, la historia nos enseña sobre el diferir de los afectos y su transformación en una narración, un plan o una estrategia.

Precisamente, la película confronta dos tipos de procedimientos, al menos. Por una parte está la fe ciega que “el perro,” un leguleyo residente de una de las casas a ser desalojadas, tiene hacia la ley y sus mecanismos. Por otra parte está la estrategia que Jacinto inventa: la creación de un sistema de tramoyas y poleas para mover toda la casa en que viven él, el perro, y los demás inquilinos a ser desalojados. Esta estrategia busca sacar cada cosa de la casa y moverla hacia la “Pajarera,” una casa que se resiste al despojo por medio de la acción armada, para de ahí transportar todo a la cima de un cerro a las afueras de la ciudad. En este sentido, la trama de la película, que es también la historia que cuenta “el paisa,” depende de cómo estas dos estrategias trabajan para diferir el inevitable despojo. Si bien, estas son de las principales estrategias, o planes, que se presentan en la película, también están otras. Está, por ejemplo, la reacción armada y violenta, a la que recurren un grupo de inquilinos de la casa vecina a donde son transportadas las cosas y los muros de la casa de Jacinto y el perro. A su vez, todas estas estrategias trabajan en contra de los caprichos del acaudalado dueño legal de las fincas, un hombre fascinado por las máquinas y demás dispositivos asociados a la captura fílmica y acústica. Con este personaje se tiende un eje de oposición que ubica a los desposeídos, como aquellos que poseen una estrategia y además construyen sus propias máquinas, en contra del que desposee, que está meramente fascinado con las cámaras de video, las televisiones y las grabadoras. Los desposeídos son creativos, los que desposeen son reactivos, parece decirnos el filme de Cabrera.

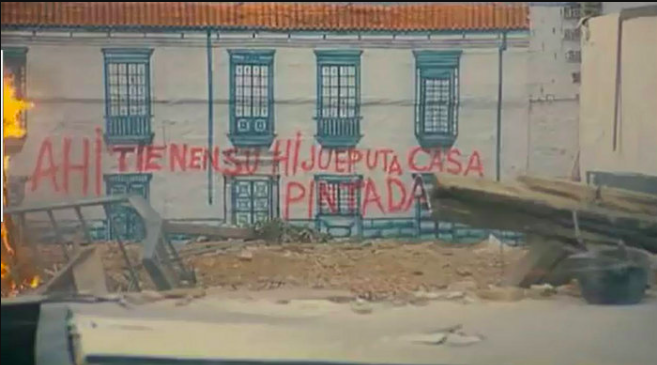

Quizá las lecciones más radicales del filme son las siguientes. Primero, el filme, en una suerte de apotropaia conservadora, es decir, en el hecho de dar por sentado que el despojo algún día llegará y que nada se puede hacer para evitarlo, nos enseña que todos, algún día, habremos de mudarnos, o de morirnos. Lázaro, el inquilino más viejo de la vecindad, es asesinado por su esposa ante la inminente urgencia de acelerar el proceso de mudanza. Por el hecho de que Lázaro esté durante casi toda la película en estado moribundo, se puede decir que la estrategia de Jacinto, en combinación con la estrategia legal del perro, son como el aplazamiento del asesinato del Lázaro. Como la fachada de la casa es tronada con dinamita al final de la película, así también la esposa de Lázaro decide acabar con la pantalla de vida que tenía su esposo. La segunda lección radical es que en lo más real se esconde un simulacro, o un artificio. En la escena que representaría el estado máximo de violencia, la explosión de dinamita que derrumba la fachada de la casa, nadie muere ni resulta herido, sino que sólo la fachada de la casa de desmorona casi como escenografía de teatro. Al fondo del lote baldío donde estuviera el inquilinato se ve una casa pintada y en el centro del espacio arde la tramoya que transportara las cosas de los inquilinos. Como si el filme se suicidara, destruyendo el espacio más creativo de toda la película, se deja ver en las ruinas aquello que fascina al acaudalado dueño pero que no puede él mismo crear ni completamente poseer: un simulacro violento, un artificio agresivo, una imagen y su violenta emergencia en lo real.