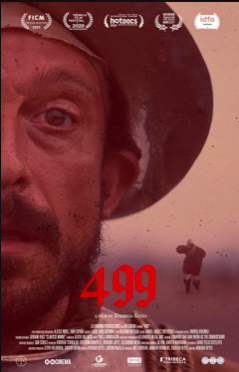

Un conquistador sin nombre naufraga en las costas de Veracruz y repite los mismos actos que en 1519 llevaron a cabo Hernán Cortés y sus tropas. Este anacrónico conquistador se empeña en repetir las ya sabidas acciones que marcaron fuertemente a la conquista (la lectura del requerimiento, la escritura de crónicas, el viaje de Veracruz a “Tenochtitlan,” la alianza con “ciertos pueblos adversarios” al dominio de Moctezuma). Sin embargo, esta vez no hay Cortés ni Moctezuma, no hay soberano ni lucha por la soberanía, sólo una violencia que resulta familiar para el conquistador anónimo y que, sorpresivamente, termina por superarlo, literalmente, quitarle su voz —nunca oímos que el conquistador hable con ningún personaje luego de que pierda la voz al leer por primera vez el requerimiento. El conquistador anónimo se encuentra con víctimas de la violencia en México: hijos que llevan el duelo de la muerte de sus padres, madres que buscan a sus desaparecidos, comunidades de autodefensa en la sierra, migrantes tratando de montarse a la bestia, exmiembros del narco, una madre que se negó al linchamiento de los violadores y asesinos de su hija y que ahora vive presa de la indignación porque los malhechores están en libertad y un sinfín de personajes que miran entre burla y extrañeza al anacrónico conquistador.

La película resuena, sin necesariamente proponérselo, con Er is wieder da [Él está de regreso] (2015) de David Wnendt. En la película alemana, Hitler regresa misteriosamente de la muerte y se da cuenta de que muchos de los sentimientos con los que simpatizó en el pasado siguen vigentes. Mientras que en Él está de regreso, gracias a la sátira, se consiguen momentos brillantes de crítica sobre la situación actual de muchos movimientos nacionalistas en Alemania, en 499 difícilmente se pudiera decir que hay una crítica. Las dos películas coinciden en que el elemento más perverso de la historia de ambas latitudes (Hitler para Alemania, un conquistador para México) regresa y encuentra demasiadas similitudes con “su versión de la historia.” Esto es, de la misma manera que Hitler vio en el nacionalsocialismo una manera para congregar los afectos de la posguerra, volverlos hábito y catalizar y mover multitudes desquiciadas, el conquistador anónimo de 499 se encuentra con un mundo incomprensible y violento que se entrega a los peores pecados imaginados por la cristiandad. Sin embargo, mientras Hitler, en Él está de regreso, se acopla bien a la sociedad que se encuentra, el conquistador anónimo no se acopla al mundo que lo recibe. De hecho, esto pudiera ser, sin quererlo, uno de los mejores atributos del filme. Esto es, dado que el conquistador anónimo está completamente desempoderado, su errancia en el “Nuevo Mundo” testifica la total incomprensión que las tierras de Mesoamerica presupusieron para Cortés y los otros conquistadores. Por otra parte, el filme parece no interesarse en esta repetición de las errancias. De hecho aquí subyacen los problemas más grandes del trabajo de Rodrigo Reyes.

El hecho de que un conquistador anónimo recorra de forma anacrónica la misma ruta que los conquistadores del siglo XVI y que, además, recupere los horrores de una violencia incomprensible (los conquistadores de Cortés veían así los ritos prehispánicos), articula, necesariamente la pregunta por los grandes ausentes en la reelaboración histórica del filme. Esto es, si el filme contrapone la violencia “incomprensible” con la que se encontraron los conquistadores de Cortés con la violencia contemporánea con la que se encuentra el conquistador anónimo, no lo hace para criticar las formas en que la violencia se articula en el presente, sino para preguntar, ¿dónde están los soberanos? Desde esta perspectiva, 499 es más una apología de la necesidad de un soberano y menos un recuento nuevo sobre la violencia en México. De hecho, la película (o documental, como se le categoriza varias veces) parece muy fácilmente deducir que la gran tragedia de nuestros tiempos no es tanto la violencia, sino la ausencia de un Cortés y un Moctezuma. Sin soberanos, hasta un conquistador debe humillarse (el conquistador anónimo se convierte en peregrino de la virgen de Guadalupe y luego en empleado en un restaurante en Nueva York). Sin soberanos, toda la violencia en México, y en otras partes, no es sino la hermenéutica que pudiera salir de cualquier cacicazgo latinoamericano: hartazgo por la descontención del Katechon que busca y demanda lastimosamente la presencia de un soberano.